We compare options when we shop for everything from laptops to lawnmowers, skimming reviews and weighing our choices. Yet when a doctor recommends a surgery that will change our bodies forever, many of us say “yes” on the spot. We treat the most consequential choices of our lives with less scrutiny than a $150 purchase on Amazon.

Medicine isn’t math. Two specialists can read the same results and see different stories, shaped by training and philosophy. A cardiologist may lean toward a stent and a functional doctor might start with diet and medication. Both can be reasonable, but neither is absolute.

A second opinion can spare an unnecessary procedure or confirm the right one. Yet many patients hesitate, unsure how to ask or whether it will offend their doctor. Learning when to pause and seek another view may be one of the most valuable skills in modern medicine.

Why 2nd Opinions Matter More Than Ever

Errors in diagnosing an illness are more common than most people realize. A Johns Hopkins

analysis found that diagnosis errors cause about 795,000 deaths or permanent disabilities each year. The National Academy of Medicine

estimates that most Americans will experience at least one such error in their lifetime. Even in an age of precision medicine, mistakes remain inevitable.

“Patients often think a second opinion means seeing another specialist,” Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, chief of hematology at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and a leading expert on diagnostic accuracy, told The Epoch Times.

“But sometimes it starts with the lab itself—getting the slides reread by an expert pathologist.”

Sekeres led a National Institutes of Health-funded study showing that experts disagreed with local pathologists in about one of every five cases.

Even when doctors agree on a diagnosis, they may not agree on what to do. One surgeon may recommend an operation, while another may suggest physical therapy. One oncologist may urge chemotherapy, while another may think that watchful waiting is the way to go.

Today, office visits average less than 18 minutes—barely enough time to describe symptoms, let alone explore their context, as we discussed in part 2. Specialists often see only fragments of a patient’s story, while electronic records overflow with templated notes that obscure individual patterns. With three in four Americans living with at least one chronic condition, the sheer volume of information can lead to miscommunication.

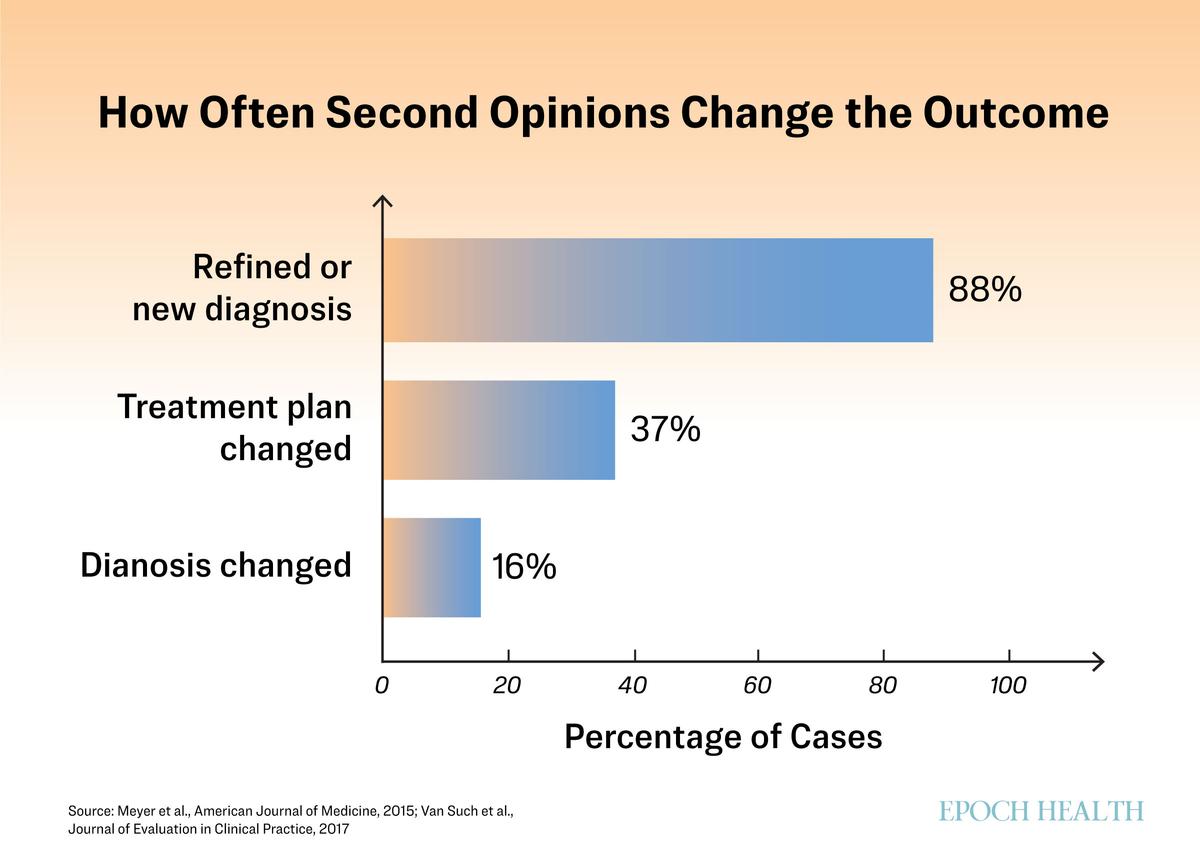

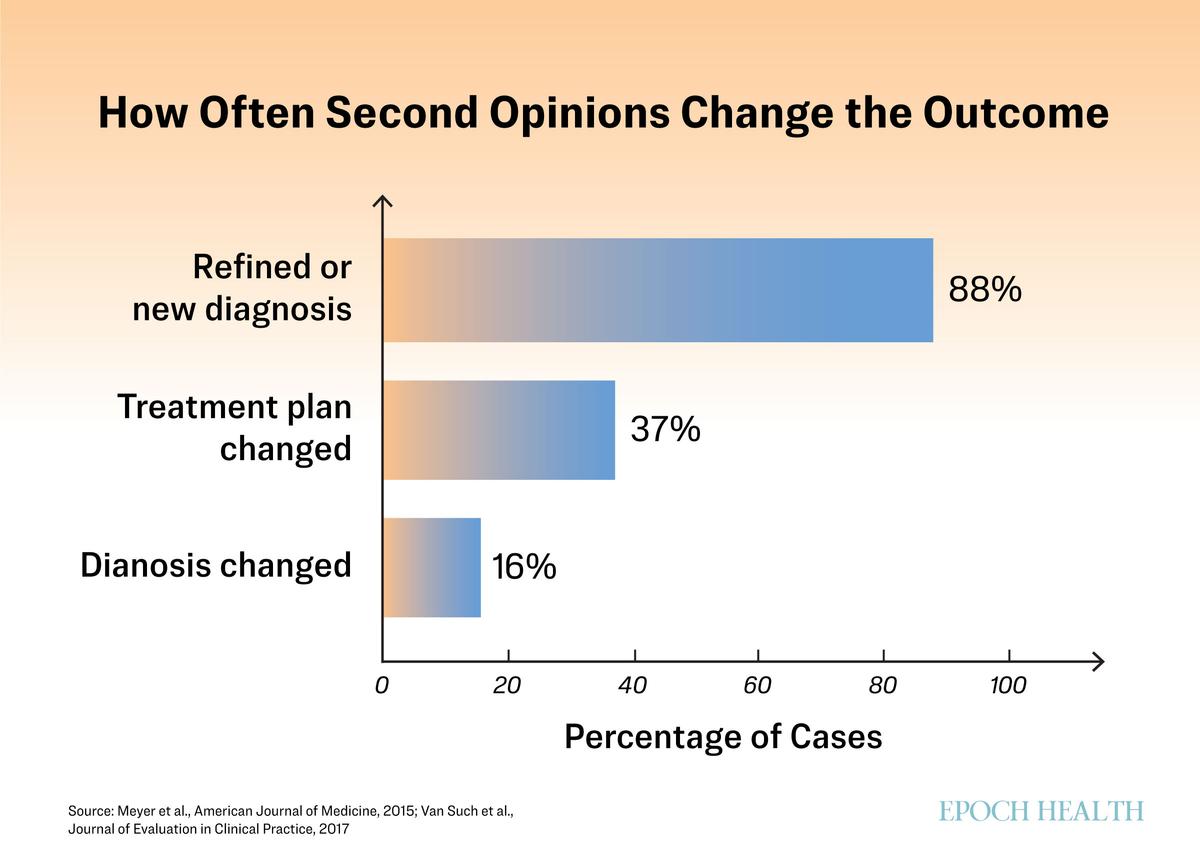

Persistence can yield enormous results. In a national review of nearly 7,000 second opinions, doctors changed the diagnosis in one of six cases and revised the treatment plan in more than one of three. At the Mayo Clinic, 88 percent of patients who sought a second opinion left with a refined or entirely new diagnosis.

“It never hurts to get a second opinion or a third opinion,” Dr. Todd LePine, an internist who practices functional medicine, told The Epoch Times. “When something serious is on the table, that pause can make all the difference.”

A second opinion changes the diagnosis or treatment plan in a significant share of cases.

When to Pause

Second opinions aren’t only for high-stakes decisions. They’re warranted anytime something feels off—when the plan seems out of step with the symptoms or the recommended treatment doesn’t make sense to you. A short pause can keep a single question from snowballing into unnecessary care.

Sekeres called pausing “medicine’s version of taking your own pulse first.”

“When a code blue is called, we’re taught to pause—to think before we rush in,” he said. “Patients facing a new diagnosis should do the same.”

Taking a breath before acting can turn panic into perspective.

Sometimes, hesitation is warranted when a treatment feels too aggressive. If surgery or a lifelong drug is on the table, ask what would happen if you tried something less invasive first. Studies show wide variation in how often doctors recommend procedures such as spinal fusion, hysterectomy, or knee replacement.

Sometimes an alarming result isn’t as dire as it sounds. Thyroid nodules, for example, are found in up to 60 percent of adults by ultrasound and often look concerning at first glance, yet the vast majority are benign and never require surgery.

The reverse can also be true: A normal result doesn’t always mean good news. Symptoms persist even as tests appear normal. Patients with so-called mystery illnesses such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which causes dizziness or rapid heart rate when standing, or conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue often discover that their tests are normal even as symptoms persist. Studies suggest that about one in five primary care visits involve symptoms that medicine can’t explain.

“Normal labs don’t always mean a healthy patient,” LePine said. “Sometimes you’re looking under the lamppost, and the problem is somewhere else.” A fresh set of eyes, whether another doctor or another specialty, can often shift the focus.

When opinions conflict, the pause becomes essential. It offers space to understand why two capable doctors might see the same case differently.

Few conditions require decisions within hours or days. Unless symptoms are worsening rapidly or the diagnosis poses an immediate threat, taking time to reassess can clarify the next step.

Use the self-evaluation below to see whether a second opinion may be helpful to you:

How to Ask Without Burning Bridges

Many patients hesitate to seek a second opinion, worried that they’ll appear ungrateful or disloyal. However, a well-framed request rarely offends. Most doctors value engaged patients, and a second opinion is widely seen as part of good care, not a challenge to authority.

A helpful way to ask is to frame it as confirmation. Many physicians appreciate knowing that you’re trying to strengthen, not question, the plan you already have. A simple line works: “I want to be sure I’m making the best decision, and another perspective will help me feel confident in our plan.”

Keeping the focus on the decision rather than the doctor sets the right tone. You’re not casting doubt; you’re gaining clarity. Openness and steadiness invite collaboration.

The fear of being labeled “noncompliant” runs deep, a legacy of medicine’s paternalistic past when the doctor’s word was final. The echo lingers, especially among older patients taught not to question authority.

“The more I practice medicine, the more I know that I don’t know,” LePine said.

He tells patients what he can and can’t answer.

Some doctors may hesitate when a patient asks for another opinion, and their reactions can be telling.

“If your doctor gets upset that you want a second opinion, that’s a red flag,” Sekeres said.

Practical steps help, too: Bring your records, imaging, and test results so both clinicians have the same information. Afterward, share what you learn. When handled openly, a second opinion can deepen trust and strengthen, not strain, the doctor-patient relationship.

How to Get a 2nd Opinion

Most health systems and insurers recognize a second opinion as a basic right, not a luxury.

Start With Your Primary Doctor

If you trust your physician, begin there. The best doctors welcome another view and often recommend colleagues they respect. Framing it as a shared step—“I’d like another perspective to be sure we’re on the right track”—keeps communication open and ensures that your records follow you.

Check Your Coverage

Most insurers, including Medicare,

cover second opinions on major diagnoses or surgeries. Some require referrals, while others let you choose a doctor directly. You can confirm your plan’s rules by calling the member services number on your insurance card or checking your online portal.

Bring Your Story, Not Just Your Chart

Your scans and labs tell one story; your experience tells another. A short timeline of when symptoms began and what makes them better or worse can reveal patterns doctors might miss.

Explore Virtual 2nd Opinions

Many hospitals now offer online second opinion programs that pair patients with top specialists. The Cleveland Clinic, for example, offers written reviews and optional video consultations for about $1,700, with many patients receiving revised treatment plans. These services expand access, although coverage varies by state. Patients should confirm whether the service counts as medical advice and whether it’s reimbursable.

Widen the Lens

Not every second opinion needs to come from another physician specialist. Physical therapists, nutritionists, or functional medicine doctors can sometimes clarify problems that resist a single diagnosis. Even acupuncturists or mind-body practitioners may spot patterns that conventional medicine overlooks.

When a 2nd Opinion Can Backfire

A second opinion can clarify—or complicate—care.

In one study of men with prostate cancer, some felt reassured by another doctor’s view, while others grew more uncertain when the advice conflicted. The goal isn’t more opinions, but clearer direction.

The pause that protects some patients can harm others. A few weeks seldom change an outcome, but for aggressive cancers or fast-moving infections, delay can mean lost ground.

Practical limits matter, too. Extra visits, travel, and time off work can add cost and fatigue. Even with insurance, navigating multiple specialists can strain patients already overwhelmed by illness. The aim is to gain clarity that provides confidence that evidence, expertise, and instinct align enough to move forward.

When to Stop Searching

At some point, the search for certainty becomes its own kind of illness. The tests come back normal, the scans unchanged, yet we keep looking because motion often feels like progress. Knowing when to stop is its own form of wisdom.

With enough perspectives, patterns emerge. When several trusted doctors see the same picture from different angles, it may be time to stop widening the circle and start moving forward.

LePine said the pursuit itself can become a stressor. Stacking appointments and tests can heighten anxiety, and for some conditions, that alone can worsen symptoms. If the search begins to crowd out rest, movement, or calm, he said, it’s time to narrow the scope and rebuild routines that steady the body.

“We like to think science gives us yes-or-no answers,” Sekeres said. “But in truth, there are many gray areas, and good doctors are always interpreting them.”

His role, he said, isn’t to dictate choices but to help patients understand them.

“My job is to educate people so they can make the decision that’s right for them,” he said. “In that sense, yes—we are our own best doctors—as long as we’re informed.”

What’s Next: Even good care can take on a life of its own. One test leads to another, and soon you’re caught in a cycle of procedures “just to be safe.” Our next article explores the medical cascade, how it happens, and how to step back before momentum replaces judgment.