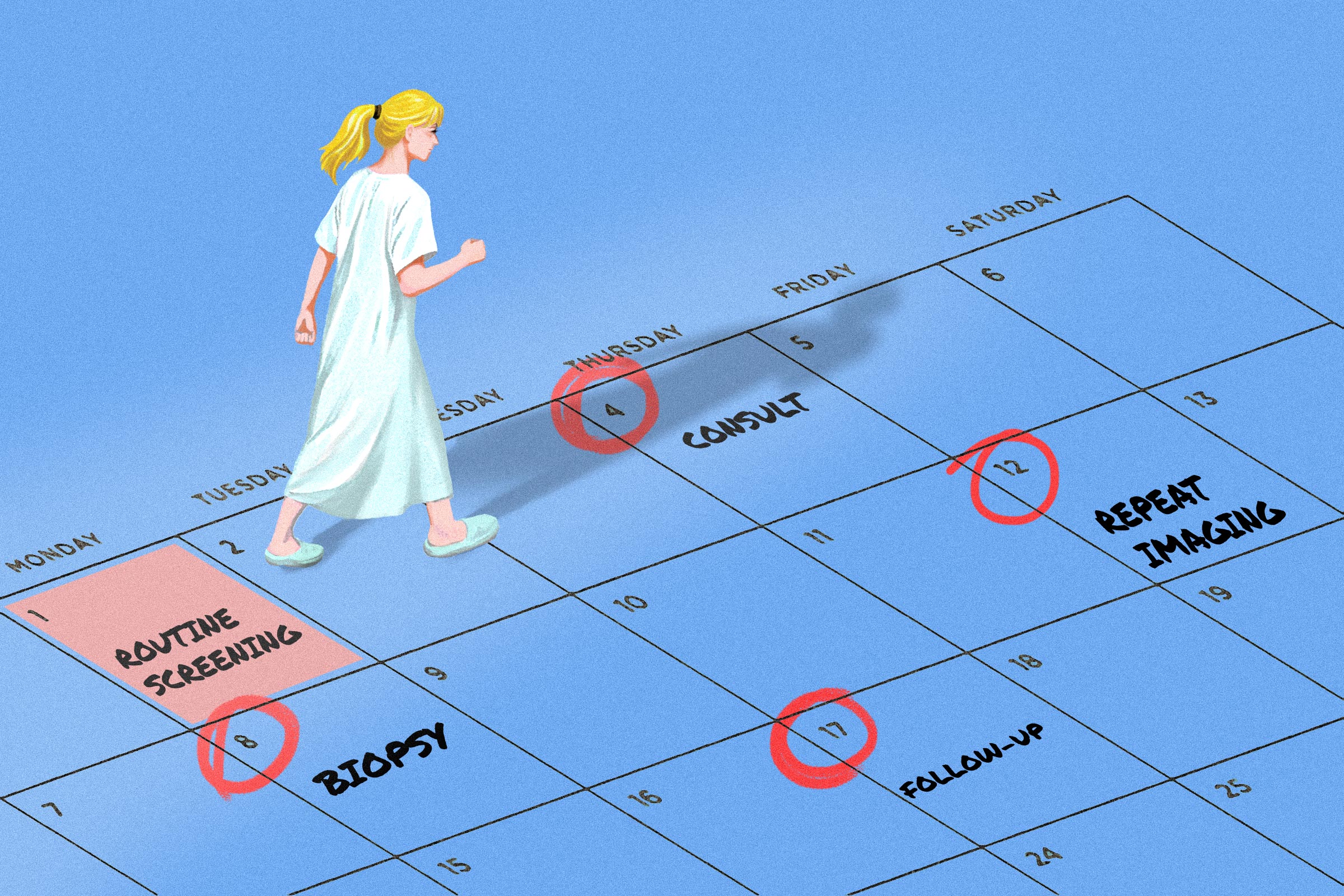

Donna Pinto didn’t give her fourth mammogram screening much thought. Like a dental cleaning, it was routine—but this time, she received a callback. Within weeks, she was being scanned, biopsied, and advised to consider surgery.

There was one problem, however: She wasn’t sure that she was sick.

Pinto’s experience highlights a problem that screening cannot always solve. Tests designed for people without symptoms are good at finding abnormalities, but far less reliable at predicting which ones will cause harm. In cancer screening, that uncertainty often pushes patients into a fast-moving chain of follow-up care—sometimes for conditions that might never have affected their health at all.

The question is not simply whether screening saves lives. It’s when, for whom, and at what cost.

Why Screening Isn’t a Simple Yes-or-No Decision

Screening is designed for people who feel well. A Pap smear looks for cervical changes before symptoms appear. A colonoscopy searches for polyps long before cancer develops. These tests differ from diagnostic exams, which are ordered to explain symptoms that already exist.

That distinction matters because screening is often asked to do more than it was built for. It is treated as a general health check when, in reality, it is a narrow tool aimed at finding disease early enough to matter.

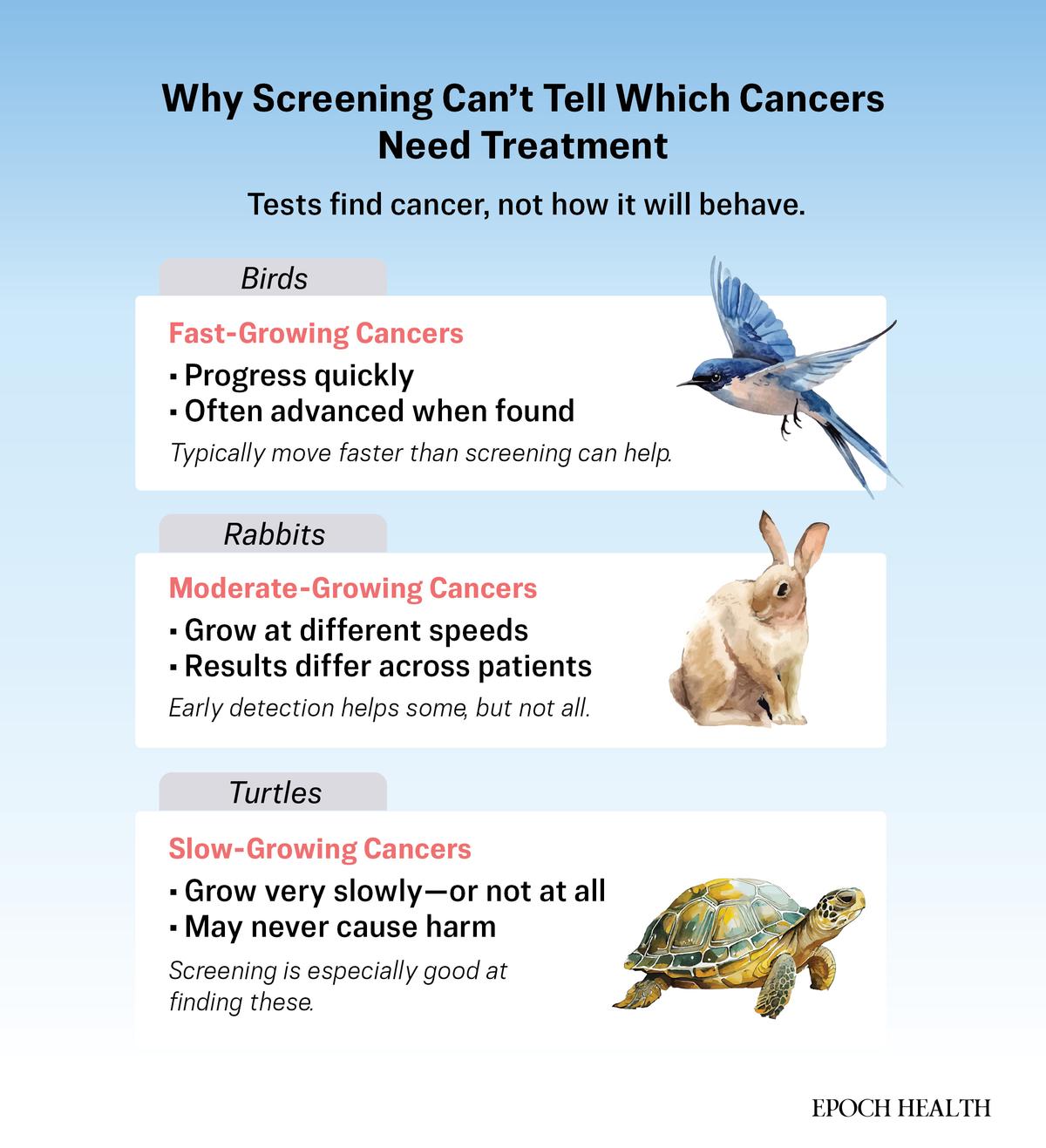

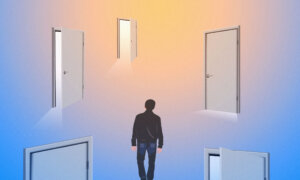

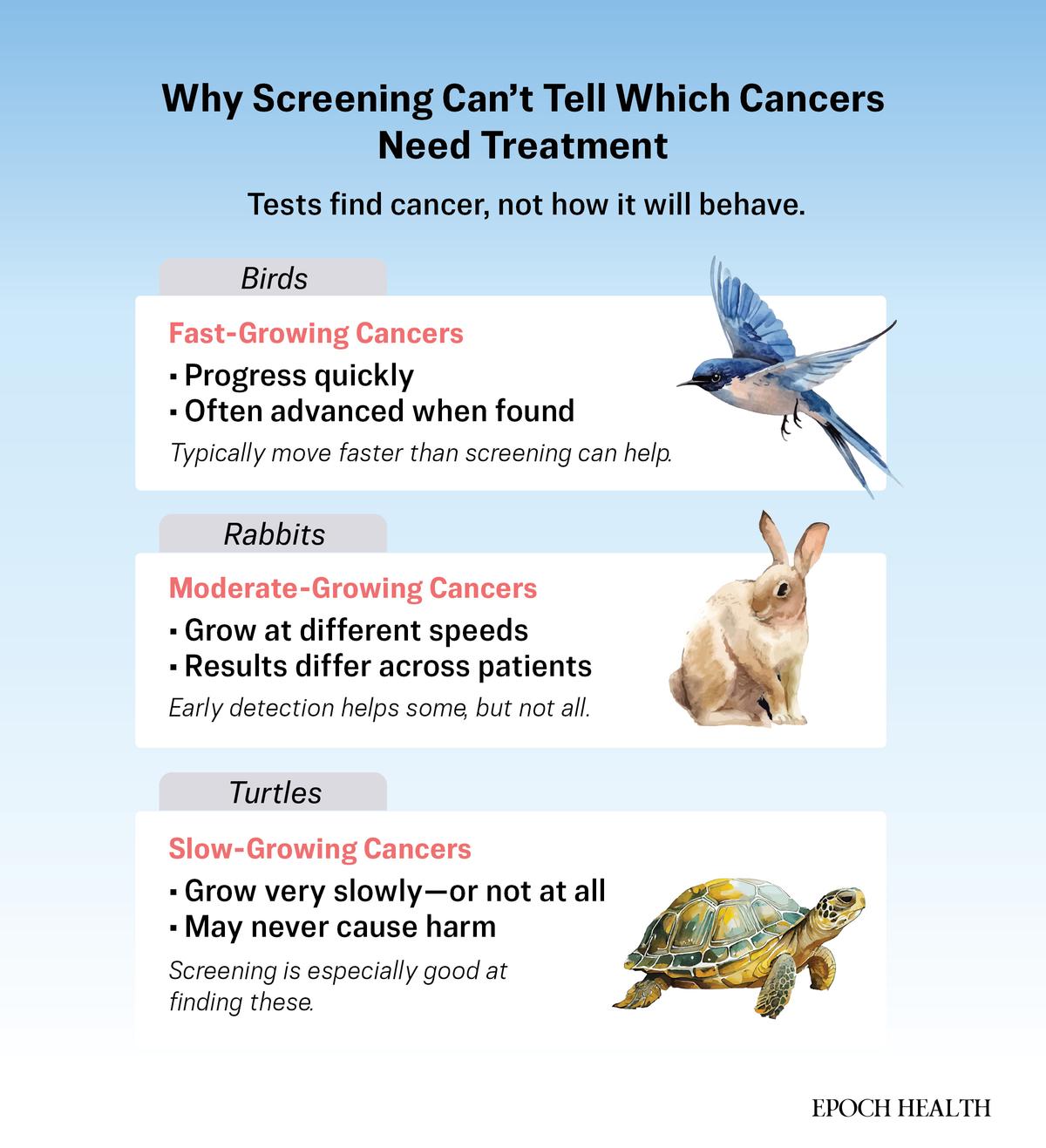

Disease, however, does not follow a single script. Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a physician and longtime researcher of overdiagnosis, describes cancers as falling into three broad groups. Some are “birds,” fast and aggressive, often advanced by the time they’re detectable. Others, he calls “rabbits,” grow more slowly and may benefit from early treatment. Then there are the “turtles,” such as Pinto’s case: real abnormalities that may grow very slowly, stop growing, or even regress—and may never cause symptoms or shorten life.

The Epoch Times

Screening struggles not with finding disease, but with knowing which disease matters.

When faced with that uncertainty, medicine tends to default to action. Abnormal findings are treated as potential threats, even when their future behavior is unknown. A test meant to offer reassurance can instead become the first step in a chain of follow-up care—scans, procedures, and decisions driven more by risk than by illness.

What Happened to Donna Pinto

Pinto’s case placed her squarely in the gray zone that screening cannot resolve.

At 44, she thought she was doing everything right. She exercised regularly, ate well, and never missed a mammogram. So when her fourth screening led to a callback, she didn’t panic. “I was a good patient,” she told The Epoch Times.

After a biopsy, she was told she had ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS—often called stage zero breast cancer.

“Although it’s considered pre-cancer,” a nurse told her, sketching diagrams on a pathology report, “we treat it as cancer.”

The abnormality was real. Its behavior was not yet known. DCIS can progress to invasive cancer—but often does not. An MRI ordered before surgery showed no clear target. At a friend’s urging, Pinto slowed down.

She said the care she was offered assumed the most aggressive outcome as the default, even though no one could say whether the cells would ever become dangerous.

“I went from perfectly healthy to being treated like a cancer patient overnight,” she said. “I had to get off the train.”

Overdiagnosis: How Common Is It?

The downsides of screening are not rare edge cases. They are common, measurable, and cumulative.

For many routine screening tests, false alarms are far more likely than life-saving discoveries. In the United States, about one in 10 women is called back after a routine mammogram, according to data summarized by the National Cancer Institute, but only a small fraction of those callbacks result in a cancer diagnosis. Over a decade of annual screening, nearly half of women will experience at least one false alarm, and up to 17 percent will undergo a biopsy for something that turns out to be benign.

Those moments carry real costs. Follow-up tests, invasive procedures, time away from work, out-of-pocket expenses, and anxiety can linger long after disease is ruled out. For some patients, the worry does not fully resolve—it becomes a standing expectation that something might be wrong.

More consequential still is overdiagnosis. The test isn’t wrong; it detects something real. However, the finding may never have caused illness, even as its discovery sets off surgery, radiation, or years of follow-up.

How often does that happen? Estimates vary widely depending on age, screening frequency, and definition. Even conservative analyses find that overdiagnosis is not rare. The National Cancer Institute suggests that 20 percent to 50 percent of screen-detected breast cancers represent overdiagnosis—real tumors that would not have caused symptoms or shortened life if left undiscovered, depending on age and screening method. An extensive 2022 U.S. analysis placed the estimate closer to one in seven among women screened every two years between ages 50 and 74.

Despite this, harms are often minimized in how screening is presented. A review of major cancer screening guidelines found that benefits were frequently emphasized while false positives and overdiagnosis received far less attention, even when evidence was strong.

For patients, the result can feel like a one-way street. Once screening begins, stepping back requires swimming against a powerful current.

How the System Nudges Toward More Testing

Even when clinicians understand the limits of screening, the structure of modern health care pushes toward action. Doctors are rarely faulted for ordering too much, yet they are for missing something. That imbalance alone favors testing over restraint.

“Even when there’s nothing we can do to lengthen life or improve quality of life, there’s a strong incentive in medicine to do something anyway,” Dr. Rita Redberg, a cardiologist and former editor of JAMA Internal Medicine, told The Epoch Times. While most clinicians are motivated by care, a fee-for-service system that pays for tests and procedures quietly reinforces the idea that action equals good medicine.

Screening healthy people is easier to schedule, easier to measure, and often better reimbursed than caring for patients who are already sick. Health systems track how many mammograms, colonoscopies, or coronary calcium scans are completed, not how often unnecessary treatment is avoided. Time and resources flow toward testing healthy people, while access for sicker patients grows tighter.

Public messaging amplifies the effect. Decades of campaigns urging early detection have made screening feel like a moral obligation rather than a medical choice. Opting in signals responsibility. Hesitation can feel reckless, even when evidence supports caution.

When screening causes harm, it rarely registers as failure. False positives are labeled as expected. Overdiagnosis is framed as the price of vigilance. The costs—anxiety, procedures, lost time, and altered lives—are absorbed quietly by patients, while the system essentially moves on to the next test.

The Epoch Times

Where Screening Helps

Screening works best under specific conditions:

- The disease must have a long silent phase before symptoms appear.

- Early treatment must meaningfully improve outcomes.

- The person screened needs enough risk and enough life expectancy to benefit.

Lung cancer screening meets those criteria for a narrow group. Among long-time heavy smokers, annual low-dose CT scans detect aggressive tumors earlier, and extensive

trials show real reductions in lung cancer deaths. For nonsmokers and light smokers, the harms often outweigh the gains.

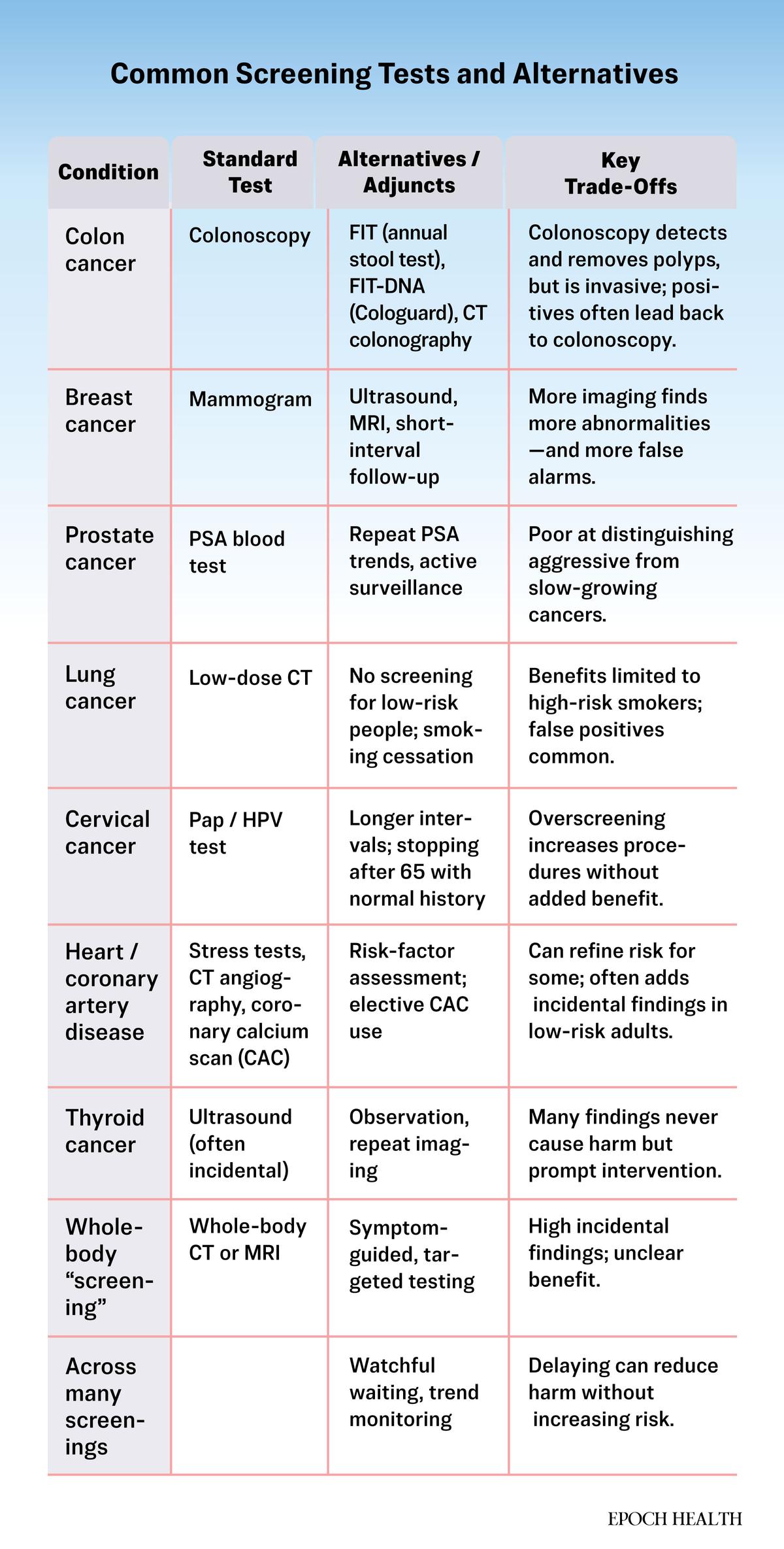

Cervical cancer screening offers another example of evidence refining practice. As understanding of the human papillomavirus improved, guidelines pulled back from annual Pap tests to longer intervals for low-risk women, without increasing deaths. Less screening, in this case, proved safer.

Colon cancer screening is more nuanced. Removing certain polyps can prevent cancer, and observational studies link colonoscopy to fewer deaths. However, a major trial in the New England Journal of Medicine found only a modest drop in cancer diagnoses—and no clear reduction in deaths—among those invited to screening. The benefit appears real, but is smaller than many assume.

Other widely used screenings show a more contested balance. Mammography and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing—both used to screen symptom-free adults for breast and prostate cancer—offer smaller mortality gains for average-risk adults and carry higher rates of overdiagnosis. Benefits vary with age, risk, and how results are acted upon.

Confusion often stems from how benefits are framed. Headlines tout relative risk reductions, a “20 percent drop in deaths,” without explaining what that means in absolute terms. For many average-risk adults, the difference may amount to one life saved for every several hundred or even thousands of people screened.

That doesn’t make screening useless. However, it does mean the benefits most people imagine are often larger than the benefits most people actually receive, while the harms are closer, more personal, and more common.

Why ‘It Saved My Life’ Stories Can Be Misleading

Few things shape public belief about screening more powerfully than personal stories. A woman says her mammogram caught cancer “just in time.” A man believes a PSA test saved his life. These stories feel definitive—and they’re hard to question.

However, stories show only what happened, not what would have happened without intervention. “Stories of success are very compelling,” Welch said, “but they can be misleading.” Many people never consider the possibility that the cancer found might never have caused harm.

One reason is statistical. Finding a tumor years before it would have caused symptoms starts the survival clock earlier. A patient may appear to have “survived cancer” for a decade, even if the disease would never have threatened their life. Mortality stays the same, but survival time looks longer.

Another reason is psychological. It’s easier to imagine the catastrophe a test might avert than the alternative—that nothing bad would have happened at all. Fear makes action feel safer than restraint, even when evidence suggests otherwise.

“Ironically,” Welch said, “part of good health is not paying too much attention to your body.” Constant testing can create its own harm, keeping people braced for trouble rather than living at ease.

Understanding these biases is not about dismissing screening. It is about placing individual stories into a wider frame, so decisions are guided by evidence and values, not by anecdotes alone.

How to Decide If Screening Is Right for You

Deciding whether to be screened is a choice, not a mandate—and one that deserves deliberation. “I don’t think people are reassured by tests,” Redberg said. “They’re reassured by a clinician who listens.”

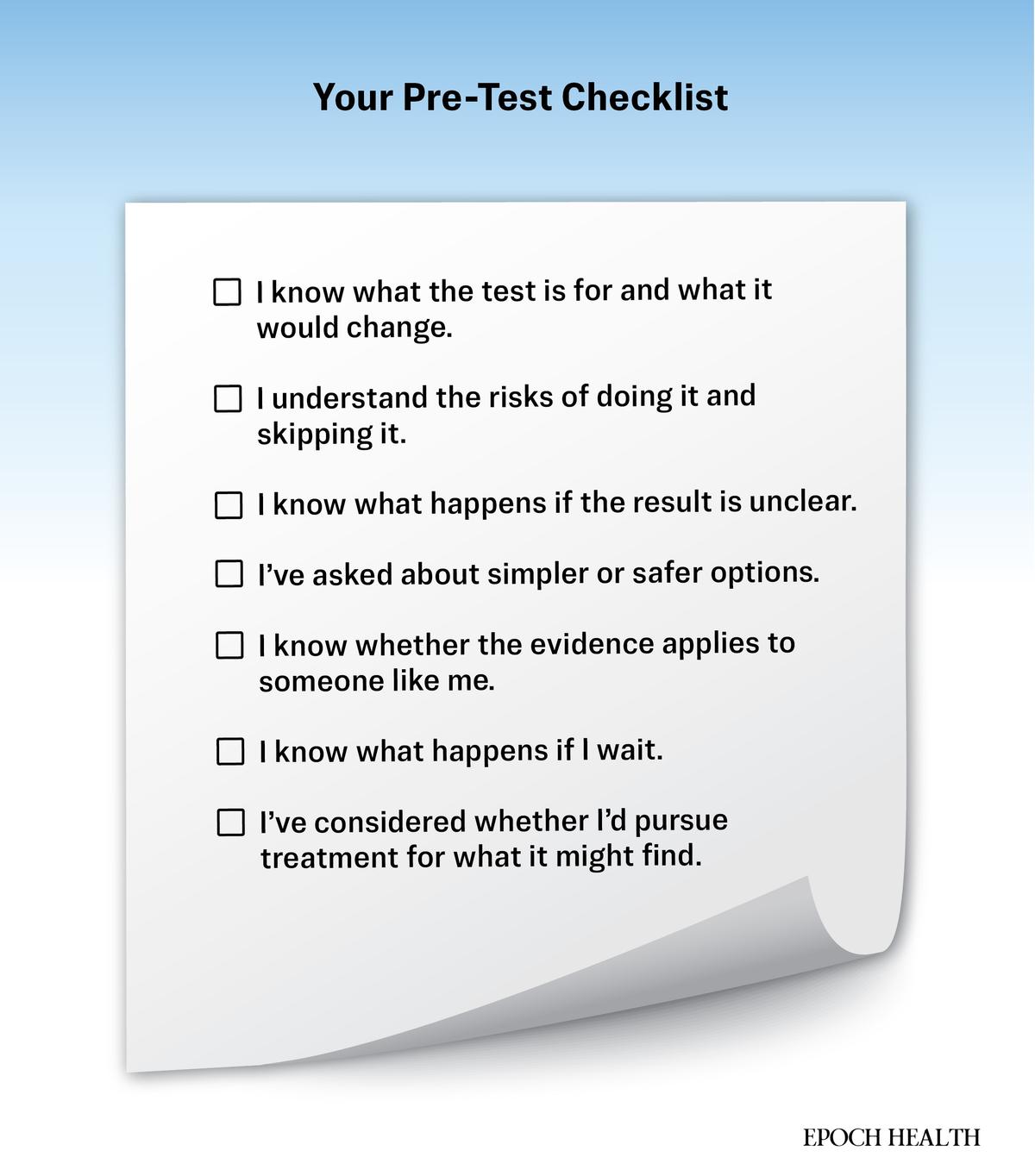

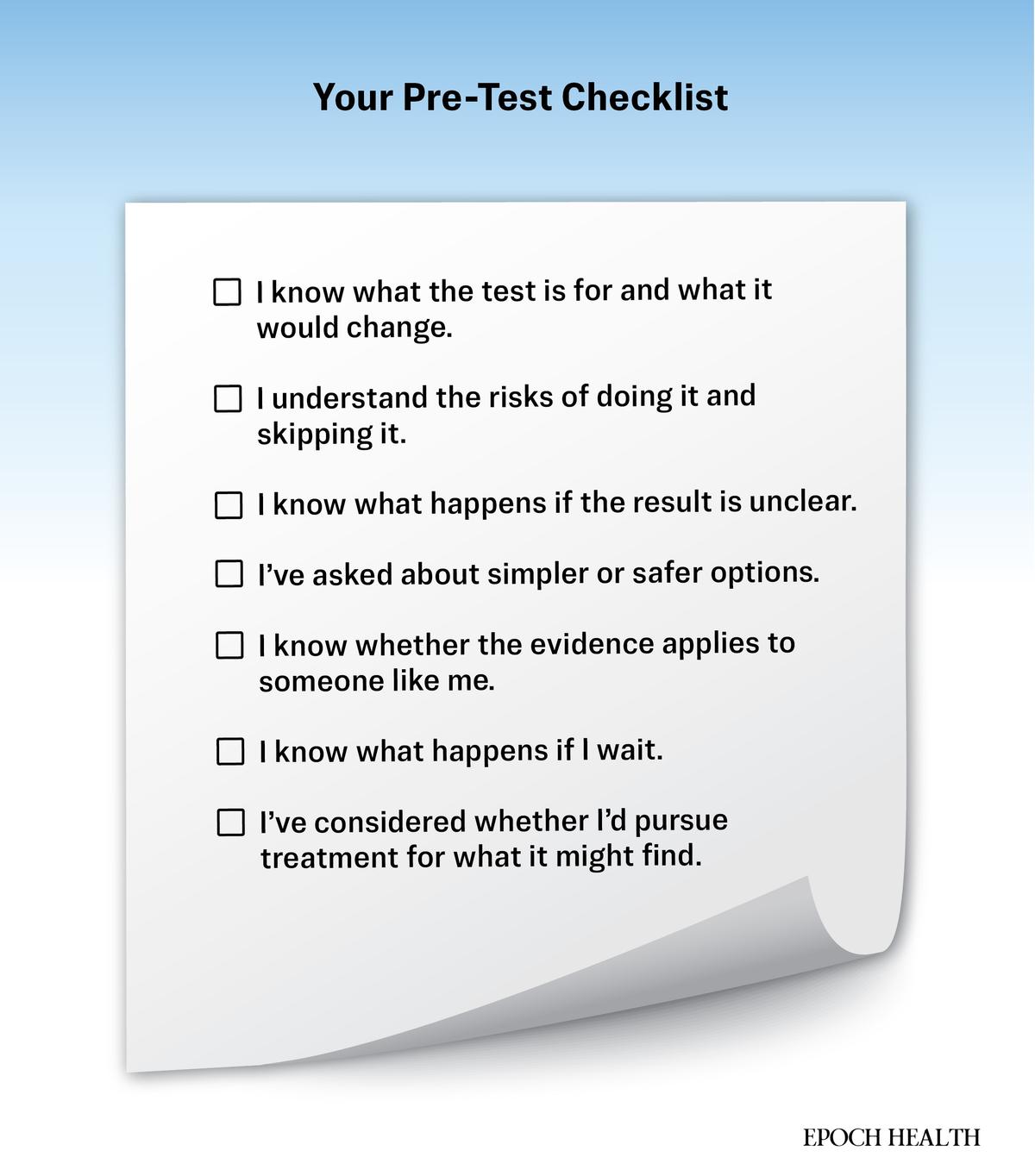

A clearer decision starts with five essentials:

1. Your Personal Risk

Family history, genetics, lifestyle, and past abnormal results can tilt the balance toward screening. For people at average risk, the benefit is often far smaller than cultural messaging suggests.

2. Your Age and Health

As people age or develop serious illnesses, the chance of benefit drops. Finding a slow-growing cancer late in life may cause more harm than good.

3. The Test’s Limits

Screening can find abnormalities early, but it cannot reliably predict which ones will become dangerous. Understanding what a test can and cannot tell you makes results easier to interpret.

4. How Results Will Change Care

A test is useful only if acting on it improves outcomes. If a positive result mainly leads to more testing or treatment with unclear benefit, waiting may be reasonable.

5. Your Values

Some people want every available data point, even if it means more follow-up. Others know that uncertainty would create anxiety rather than clarity. Screening is not a measure of diligence or virtue. It’s a tool. The right choice is the one that fits your goals, your tolerance for uncertainty, and what the test can realistically offer.

A few additional questions to ask your doctor:

- What’s my personal risk for this disease?

- How often does this test lead to false alarms, and what would follow?

- How would a positive result change my care?

- What are the risks of the test itself?

- What happens if I wait?

- Does this choice match my comfort level and goals?

A good screening decision doesn’t hinge on fear or slogans. It rests on informed consent and honest conversations.

The Epoch Times

Alternatives to Standard Screening

Skipping or delaying a screening test is not the same as ignoring health. Screening can detect disease earlier, but it does not prevent it. For many of the conditions people worry about most—heart disease, diabetes, some cancers—risk is shaped far more by daily habits than by what appears on a scan.

What matters more, Welch said, is living well—“eat real food, move regularly, [and] find purpose”—rather than chasing every possible early detection test.

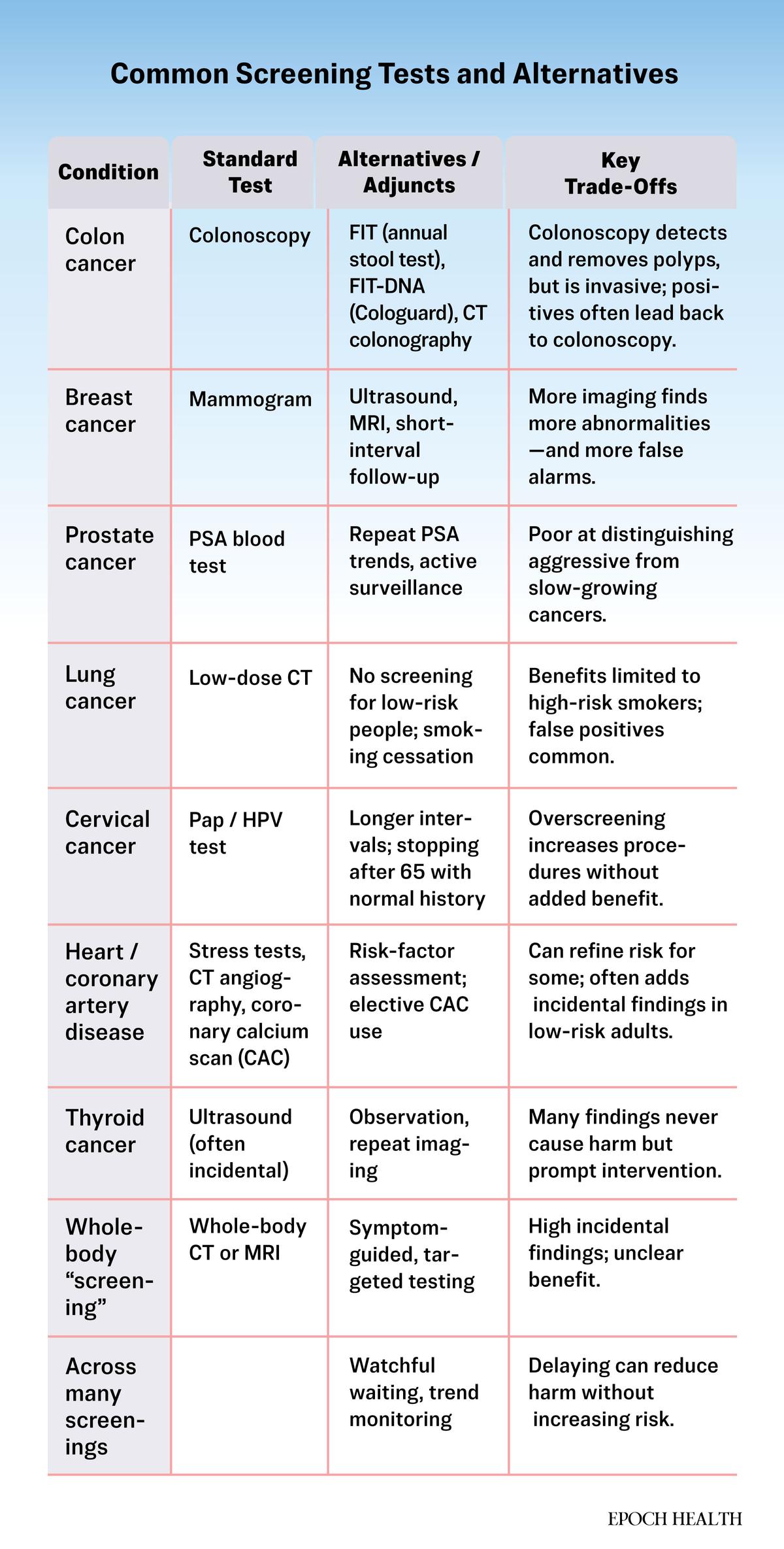

Lower-intensity screening options can also offer a middle ground. For colon cancer, annual stool-based tests can reduce risk without anesthesia or invasive procedures. In breast care, shorter-interval follow-up or targeted ultrasound may clarify findings without immediately escalating to surgery, though they come with trade-offs of their own. In some cases, careful physical exams and watchful waiting remain reasonable first steps.

None of these approaches is risk-free—but neither is reflexive testing. The goal is not to eliminate uncertainty—it’s to choose how much of it you’re willing to live with, and what kinds of harm you’re trying to avoid.

Screening is not the cornerstone of good health. It is one tool—powerful for the right person, at the right time, and far less useful when treated as a moral obligation or a substitute for prevention.

“Screening is a choice,” Welch said. “It’s not a public health imperative.”

The real question isn’t whether screening is good or bad. It’s whether this test, now, for you, is likely to change your life for the better.

What’s Next: The next article explores how creating a “medical second brain” can help patients keep their health information organized—and make more deliberate, less reactive decisions when those choices matter most.