On winter evenings in Great Neck, New York, a young Frank Ittleman would watch his father step in from the cold, fedora on his head and a heavy black bag in hand. The front rooms of their small house doubled as a medical practice, lined with dark-wood cabinets with a hulking X-ray machine pressed against the wall. In the basement, X-ray films dried in a darkroom carved out of the coal chute.

Patients came by train from Brooklyn, and Dr. Felix “Big Frank” Ittleman picked them up at the station, treated them in the parlor, then drove them back. “People said talking to him was like talking to a priest,” his son, Frank Ittleman, told The Epoch Times. “Only better.”

Dr. Felix Ittleman on a winter house call in Great Neck, N.Y., circa 1950. (Photo provided by Frank Ittleman.)

The medicine of that era saved fewer lives, but it held a kind of attention that shaped the encounter. Doctors listened without rushing and sensed the worries behind a patient’s words—what Ittleman would later call “the complexities of the soul.” Presence was part of the diagnostic tool kit, not an afterthought.

As care shifted into larger systems, the work changed. Payment began to reward what could be coded rather than the time spent understanding a patient. Technology expanded what was possible, yet connection narrowed. Visits shortened. Familiar faces disappeared. The small cues that once guided a diagnosis grew easier to miss.

The result was progress with a missing piece. Doctors who once crossed blizzards to reach patients now struggle to reach them through an avalanche of screens, rules, and codes.

Some physicians are trying to bring those elements back together, pairing the precision of modern medicine with the attention that once anchored care, an effort to restore the one thing both patients and doctors have steadily lost: time.

How Everyday Care Was Rebuilt for Speed

By the time Ittleman entered medicine in the 1970s, the world that shaped his father was already fading.

House calls—once nearly 40 percent of visits in the 1930s—were rare. Visits that once unfolded at a patient’s pace were replaced by schedules built to meet rising demand and new clinical capabilities.

The shift mirrored deeper changes in U.S. health care. Mid-century doctors were generalists—delivering babies, setting fractures, treating infections. After World War II, expanding hospitals and new technologies—imaging, intensive care, laboratory diagnostics—made specialization both possible and necessary. As the clinical toolbox grew, independent practices shrank, and care was consolidated into larger systems. Today, roughly 77 percent of physicians work for hospitals or corporate groups.

Policy sped the shift. When Medicare and Medicaid launched in 1965, they broadened access to care but tied reimbursement to procedures and measurable services. Time—once the currency of a physician’s work—was no longer what the system paid for. It was easier to price an X-ray than a conversation.

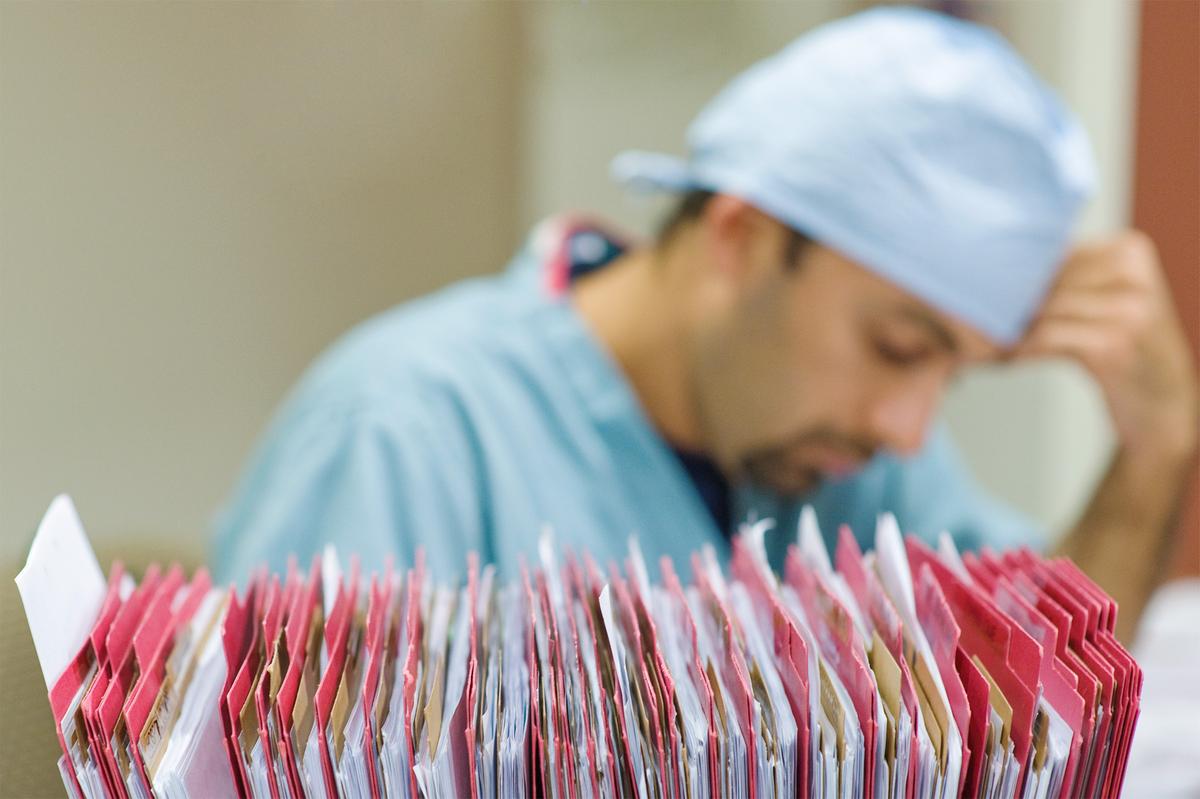

As chronic disease rose, paperwork multiplied, and malpractice fears nudged testing upward. By the 1990s, hospital mergers and productivity targets further compressed care. Bit by bit, a system built itself between doctors and their patients. Today, clinicians spend nearly two hours on documentation for every hour of face-to-face care.

As chronic disease rose, paperwork multiplied. Clinicians spend nearly two hours on documentation for every hour of face-to-face care. (Reza Estakhrian/Getty Images)

Surveys reflect the consequences. U.S. patients experience some of the shortest visits and weakest continuity among high-income nations, while physicians report some of the highest rates of burnout. Both are downstream effects of a system optimized for throughput, not presence.

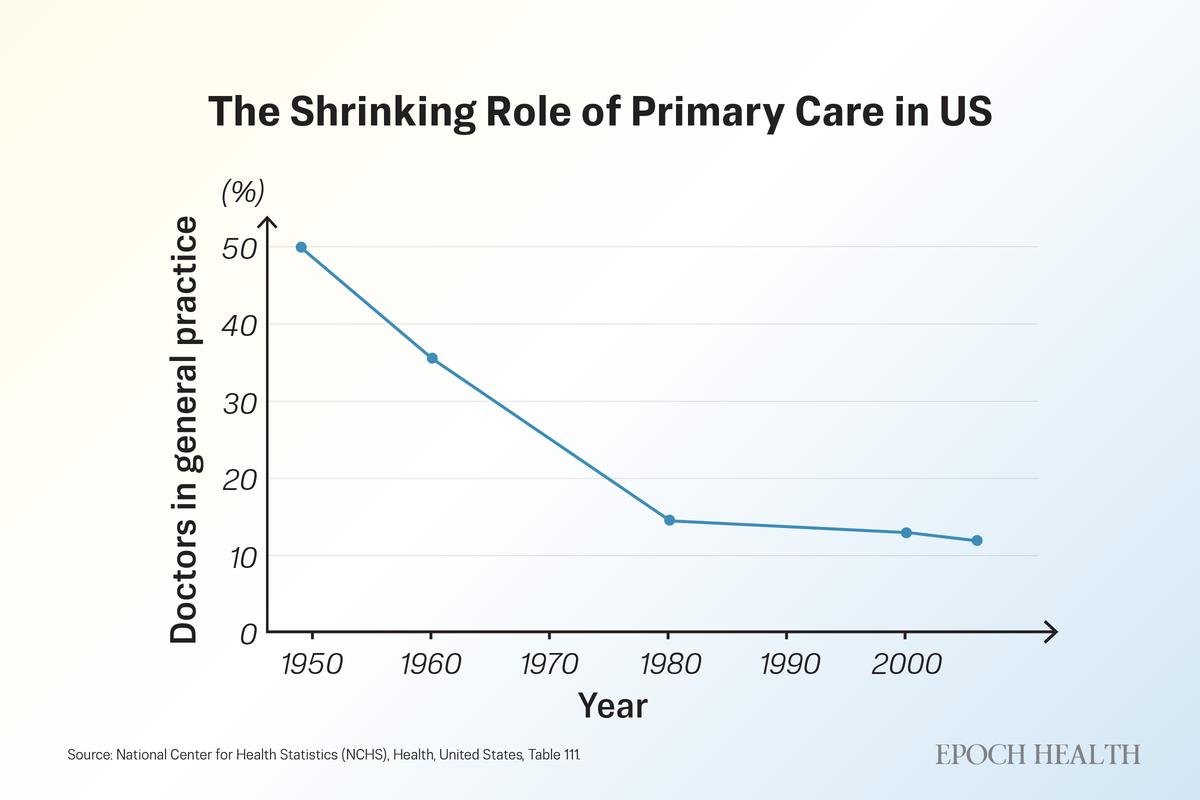

One of the quiet drivers of that shift has been the erosion of primary care. Over several decades, fewer physicians entered or remained in generalist roles, even as patients lived longer with more chronic and complex illnesses. Primary care physicians, the clinicians best positioned to integrate symptoms, context, and care over time, became harder to find.

As primary care thinned, the system adapted to its absence. Patients without a primary doctor moved between urgent-care centers and emergency rooms, specialists, and hospital networks. Responsibility fragmented. Medicine grew more capable, but less anchored.

What that anchor once looked like is still vivid to those who lived inside it.

The share of U.S. physicians working in general practice and family medicine has steadily declined since the mid-20th century. (The Epoch Times)

The Continuity That Once Defined Care

Brian Harwood remembers evenings in the 1950s when neighbors crowded the hallway of his family’s home in Waterbury, Vermont, waiting to see his father, Dr. Charles Harwood, without appointments. “People would just come and wait,” he told The Epoch Times. “He never rushed a patient.”

The elder Harwood mixed his own medicines and poured cough syrup from five-gallon jars, then headed out in deep winter when calls came—sometimes by sleigh, sometimes in a car fitted with snow tracks. When cash was tight, payment might be a jar of quarters or a side of beef.

Dr. Charles Harwood became an early adopter of Blue Cross Blue Shield when it began operating in Vermont. (Photo provided by Brian Harwood.)

For many who lived through that era, feeling cared for began with being known. As a child in the 1960s, Susan Hooper, now 73, remembers her pediatrician, Raymond “Doc” Towne, vaccinating classmates at school and treating every sore throat. Patients walked in expecting to be seen that day by someone who knew them, sometimes, quite literally, from birth.

Her experience today looks different. Hooper told The Epoch Times she recently waited seven months for a spinal ablation—a procedure that did not exist in her childhood and no neighborhood doctor could have performed. But the wait, at a short-staffed clinic later absorbed into a larger network, highlighted something else that had thinned: the sense of being known. “You don’t call and have someone know who you are anymore,” she said. “That’s different.”

Research suggests continuity offers more than comfort. A 2018 systematic review found that patients who consistently saw the same doctor were less likely to die during follow-up, echoing research that ties continuity to fewer hospitalizations. That cumulative understanding often helped a doctor notice when something was off. It gave physicians a window into what charts cannot hold—the fear, loneliness, and loss of purpose that shape modern illness as much as symptoms do.

As small practices have closed or been absorbed into bigger systems, that thread has frayed. Patients now move among rotating clinicians, urgent-care sites, and specialists—a model that broadens access to expertise but often scatters the relationships that once grounded care. Records follow patients; relationships rarely do.

Continuity never guaranteed perfect care, but its absence changed the feel of medicine—when a visit begins not with recognition but with the need to explain yourself all over again.

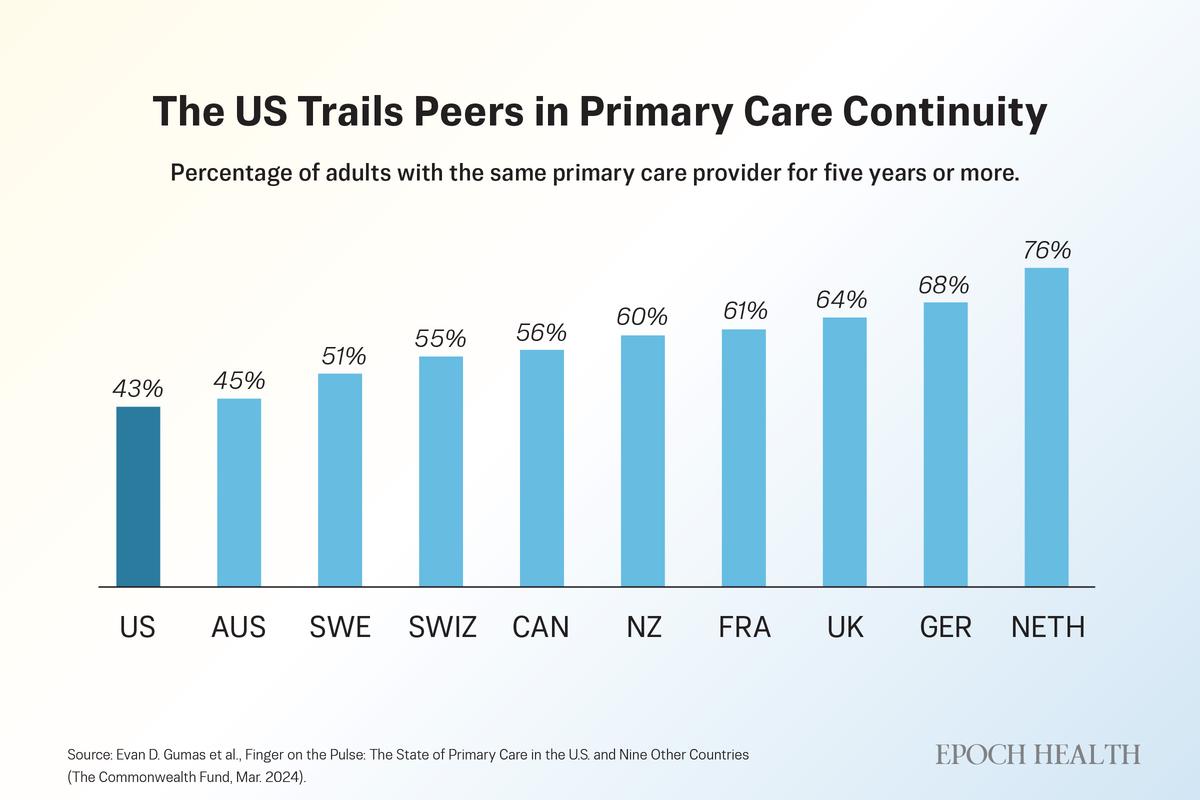

Fewer than half of U.S. adults report having the same primary care provider for five years or more, trailing most peer nations. (The Epoch Times)

Lost Skills That Once Anchored Care

Ittleman uses skills that younger doctors may learn, but rarely have time to develop. He sits at eye level, rests a hand on a shoulder, or waits long enough for a patient’s real concern to surface. “I never hesitate to touch a patient,” he said. “That’s how you understand someone. That’s how you build trust.”

Small gestures like these created space for stories that didn’t fit neatly into a chart. In a randomized trial, patients whose doctors sat rather than stood perceived the visit as longer and more compassionate, even though the visit lasted the same amount of time. Listening has followed a similar path. In another study, clinicians interrupted patients after a median of 11 seconds—often before learning why the patient had come.

The physical exam has drifted in the same way. A skilled clinician can still catch what machines miss—subtle swelling, a change in breathing, unease in a patient’s eyes—but its deeper value lies in human contact, in making room for fears patients struggle to name. That kind of listening takes time, a resource clinicians have the least of.

“We don’t set aside the time to talk to patients, to find out what really makes them tick,” Ittleman said. The result, he added, is not a loss of compassion, but a loss of the conditions that allow it to function.

In a perspective published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Paul Hyman, an internist at MaineHealth Maine Medical Center, observed how touch had become an afterthought as visits grew more compressed and technology took over. When touch disappeared, its absence clarified what it had long provided—it slowed the visit, grounded the story, and revealed what no scan could.

Ittleman worries about what’s lost when AI drafts visit notes. To him, the medical record was never just documentation; it was a record of a relationship. “The note is precious,” he said. “It should reflect the intimacy of what happened in that room, not just the codes.”

He holds onto that ethic in small ways. When patients die, he writes handwritten letters to their families, explaining what happened and acknowledging any uncertainty or error. For many families, those letters become part of the healing.

To Ittleman, the erosion of listening and touch carries a cost that cannot be measured on a monitor. “Doctors today,” he said, “have lost the ability to deal with the complexities of the soul.”

The Part Nostalgia Leaves Out

For all the warmth in those memories, mid-century medicine was far from idyllic. Pacemakers were the size of car batteries. Syringes were reused until their needles dulled. Heart attacks were often fatal. Many cancers were found only after they had spread. Infant and maternal deaths were far higher. Life expectancy at mid-century was nearly a decade shorter than it is today.

Hooper knows that gap firsthand. When she was an infant, her mother grew exhausted and lost weight, symptoms doctors initially dismissed as the strain of caring for four children. Exploratory surgery later revealed advanced cancer throughout her abdomen. She died months later. “I do wonder if, with health care like it is today,” Hooper said, “something would have been picked up sooner.”

Ittleman is quick to push back on any rose-colored view of his father’s era. Care was compassionate, he said, but profoundly constrained. “You have to remember what we couldn’t do. We didn’t have the drugs, the imaging, the operations we have now.”

Over four decades in cardiac surgery, he watched those tools transform what was possible. Patients who would not have survived his father’s time now went home to their families. “Medicine has become incredibly sophisticated,” he said. “What we can offer now is monumental compared with what my father had.”

The risk, he said, is not that progress went too far, but that in making room for everything medicine can do, the system crowded out the parts of care that never depended on technology. It is possible to save more lives and still lose something essential in the process.

The Quiet Return

If the past cannot be reclaimed, the question becomes whether its most human elements can be reassembled inside modern medicine.

Across the country, physicians are quietly rebuilding care around time. In direct primary care practices, patients pay a monthly fee in place of insurance for routine services. In concierge medicine, an annual retainer supports smaller patient panels.

In both models, doctors see fewer patients and spend more time with each one. Same-day appointments are common. Communication is often direct. Early studies link these approaches to fewer emergency visits, stronger continuity, and lower rates of clinician burnout.

Costs vary widely, from modest monthly payments—sometimes under $75—to higher-end retainers. Their appeal reflects a growing willingness to trade breadth for time, continuity, and access.

One of those patients is Sandy Lawrence, an 81-year-old Houston woman who told The Epoch Times that she spent years feeling rushed through traditional care. She now pays a yearly fee to stay with her internist, has her cellphone number, and hears back quickly. “It’s like having a doctor who actually has time again,” she said.

Medical education is beginning to reflect the same lesson. Some training programs are reviving bedside-skills instruction that emphasizes observation, touch, and direct supervision, responding to evidence that those abilities erode quickly under pressure. Others use reflective writing, humanities-based courses, or extended clinical placements to slow trainees down long enough to see patients as whole people rather than a series of problems to solve.

Ittleman distills that ethic for his trainees into four sentences that he considers more enduring than any device: I made a mistake. I’m sorry. I don’t know. I will find out.

“If you can say those honestly,” he said, “you’ll be a good doctor, no matter what technology you have.”

Taken together, these efforts look less like a return to the past than a recalibration. Modern medicine will continue to advance, but the parts of care patients remember most—being known, being heard, and being cared for—still depend on time, presence, and attention.

That may be the clearest path back to healing.