In 1833, Sam Houston (1793–1863) left Tennessee for Texas, where he opened a law practice and soon joined the rebellion against Mexico.

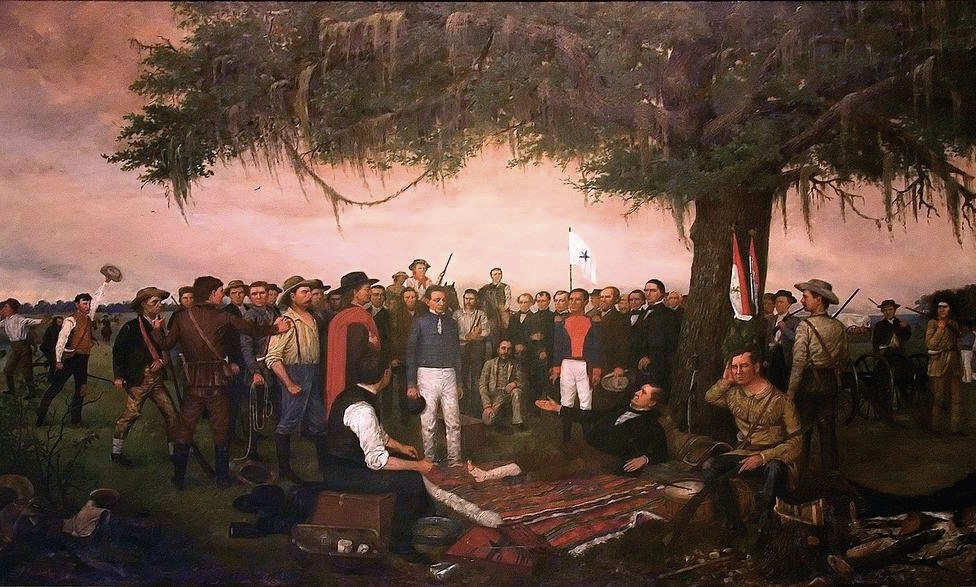

After being commissioned a major general in the Texas Army in 1835, Houston and his men won the Battle of San Jacinto the following year, shouting “Remember the Alamo!” as they surprised and defeated the forces of Mexican Gen. Santa Anna in less than 20 minutes. That same year, Texans elected him as the first president of the Republic of Texas, and a new town, Houston, bore his name.

A detail from Henry Arthur McArdle’s 1898 painting of the Battle of San Jacinto that hangs in the Texas State Capitol building. Photograph by J. Williams, 2003. (Public Domain)

Sam Houston served a second term as the Republic’s president. Once Texas gained statehood, which came to pass in large part from his efforts, he was one of the two men his state first sent to the U.S. Senate. In 1859, his fellow Texans elected him governor. By then, his name was practically synonymous with America’s largest state.

Less than two years later, however, a good many voters, including some of his own supporters, were calling for his resignation publicly, and some even for his death.

Houston’s stand against secession had opened the floodgates of hatred.

The Road to Texas

Born in the Shenandoah Valley in 1793, Houston moved with his family to Eastern Tennessee, where, as a teenager, he ran away from home and lived with a band of Cherokee for almost three years. They gave him the name Co-lon-neh, meaning “The Raven.”

During the War of 1812, Houston joined the Army and fought the Creek Indians under Andrew Jackson at Horseshoe Bend (in what’s now Alabama). Impressed by the young man’s courage—Houston suffered wounds that plagued him for the rest of his life—Jackson took him under his wing and encouraged his political ambitions. Over the next decade, Houston earned his law degree and served in several public offices before being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Elected governor of Tennessee in 1827—he is the only person in our nation’s history who served in that capacity in two states—Houston was seeking reelection when his marriage of only 11 weeks ended for reasons unknown today. The ensuing scandal sent him reeling back to the Cherokee, where his battle with the bottle brought him a new name, “Big Drunk.”

And then he headed west to Texas.

Sam Houston, circa 1850. (Public Domain)

Warnings Ignored

Though a slaveholder, Houston opposed the expansion of slavery into the Western territories and states. He was, for instance, the only Southern Democrat in the Senate who voted against the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed voters to decide whether their states should allow slavery. Even then, “The Raven” feared the growing rift between the North and South would lead to violence and a collapse of the Union.

When Houston became governor of Texas in 1859, his misgivings were coming to pass. Just before the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln as president, which was the match in this powder keg, Houston sounded the alarm in a speech. In words applicable to some in our own time, he blamed firebrands for the impending explosion:

“There is no longer a holy ground upon which the footsteps of the demagogue may not fall. One by one the sacred things placed by patriotic hands upon the altar of our liberties, have been torn down. The Declaration of our Independence is jeered at. The farewell counsels of Washington are derided. The charm of those historic names which make glorious our past has been broken, and now the Union is no longer held sacred, but made secondary to the success of party and the adoption of abstractions.”

In this same address, Houston spoke of his own love of country:

“It has been my misfortune to peril my all for the Union. So indissolubly connected is my life, my history, my hopes, my fortunes, with it, that when it falls, I would ask that with it might close my career, that I might not survive the destruction of the shrine that I had been taught to regard as holy and inviolate, since my boyhood. I have beheld it, the fairest fabric of Government God ever vouchsafed to man, more than a half century. May it never be my fate to stand sadly gazing on its ruins!”

Principles Over Power

Unfortunately for him and the state of Texas, that hope died in January 1861 when the legislature called for a convention, which then voted to leave the Union on Feb. 1. As governor, Houston demanded a referendum of voters and campaigned against secession. Before a hostile audience in Galveston, he painted a clear

picture of the outcome of this folly:

“Some of you laugh to scorn the idea of bloodshed as the result of secession. But let me tell you what is coming. … Your fathers and husbands, your sons and brothers, will be herded at the point of the bayonet. … You may, after the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, as a bare possibility, win Southern independence … but I doubt it.”

The Sam Houston Monument, designed by Enrico Cerracchio, was erected in Hermann Park in downtown Houston, Texas, on Aug. 16, 1925. (Trong Nguyen/Shutterstock)

On March 2, Texas became the seventh state to leave the Union. Faced with the choice of taking a loyalty oath to the Confederacy or resigning his office, Houston brooded on his options. He stayed awake the entire night of March 15, pacing back and forth in the ramshackle executive mansion, a dark night of the soul that one of his daughters later described as “wrestling with his spirit, as Jacob wrestled with the angel.” In the morning, he entered the kitchen and said to his wife, “Margaret, I will never do it.”

Later that morning, when the speaker of the convention summoned him to appear by calling out “Sam Houston!” three times in a loud voice, Houston remained in his office in the basement of the building, whittling on a piece of pine. The convention then proclaimed the governor’s chair vacant, and Houston’s long life in public service ended.

Two years of war and privation changed the minds of many Texans. By the summer of 1863, local newspapers were reporting growing support for Houston for another stint as governor, with the likelihood that he would win that race. On July 26, however, “The Raven” died on his ranch near Huntsville.

Houston’s noble defeat should remind all Americans of the damage done when ideology or the appetite for power takes precedence over love of country.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc