In 1751, Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond founded the Pennsylvania Hospital, the first such institution in the colonies. Among the patients admitted to the hospital were the mentally ill. A 2013 article describes their treatment:

“For the people of Philadelphia, it was considered a pastime to come to the hospital and peer into the rooms of the insane to witness their episodes. The patients were douched alternatively with warm and cold water, their scalps shaved and blistered; they were bled to the point of syncope (transient loss of consciousness due to inadequate blood supply to the brain), purged until the alimentary canal failed to yield anything but mucus, and, in the intervals, were kept chained. The keepers were given whips and they were allowed to use them on patients that were not passive. These methods were not meant to be cruel to the patients; they were what were deemed necessary to help them in their recovery.”

Then Dr. Benjamin Rush (1745–1813) arrived.

"The Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia," circa 1811–1813, by Pavel Petrovich Svinin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. (Public Domain)

A Founding Father

Like Franklin, Jefferson, and others of his time, Rush was a man of many interests and talents. An early supporter of the American Revolution and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, he was a national figure and a prolific writer, an outspoken advocate for public schools, educational opportunities for women, and the abolition of slavery.

For 45 years, Rush also practiced medicine. Trained in America and then in Scotland and England, in 1769 he both taught medicine and opened a practice in Philadelphia, tending the poor along with the well-to-do.

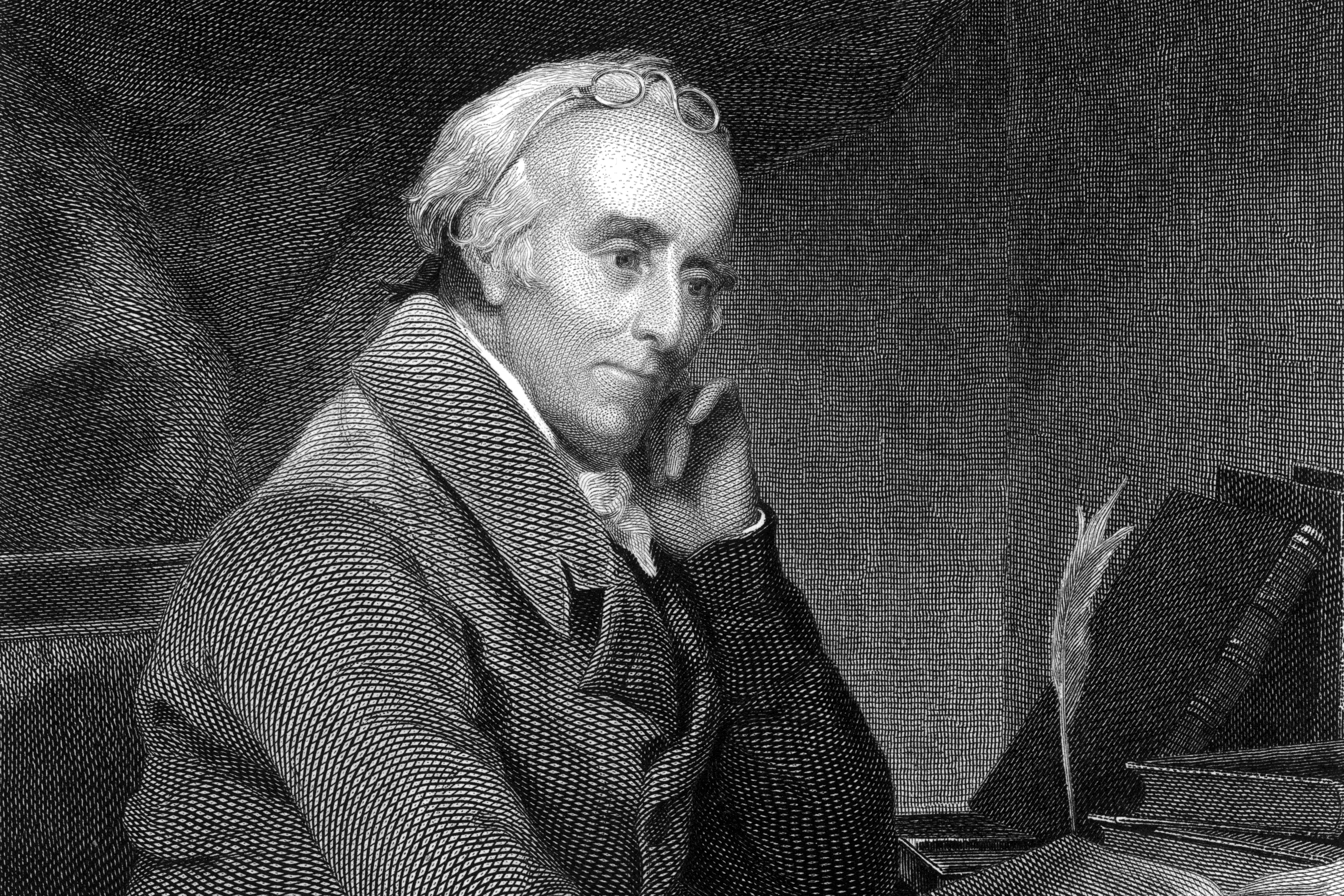

A portrait of Benjamin Rush, 1802, by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin. Library of Congress. (Public Domain)

Believing that the circulatory system was the cause and carrier for most human diseases, Rush made free with the lancet, bleeding patients with such vigor, especially during the city’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic, that some of his fellow physicians considered him more an assassin than a healer. As we know today, his critics were correct, yet Rush’s inability to brook criticism—his ego often dwarfed his knowledge—only fortified his obstinance.

Most importantly, though, he also instituted more humane treatment for the mentally ill.

A Trailblazer

In 1783, Rush joined the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital. Having already taken an interest in the mentally ill, he began treating some of the hospital’s inmates. In addition, he delivered lectures to the medical staff, linking illnesses like depression and mania to both the body and the brain.

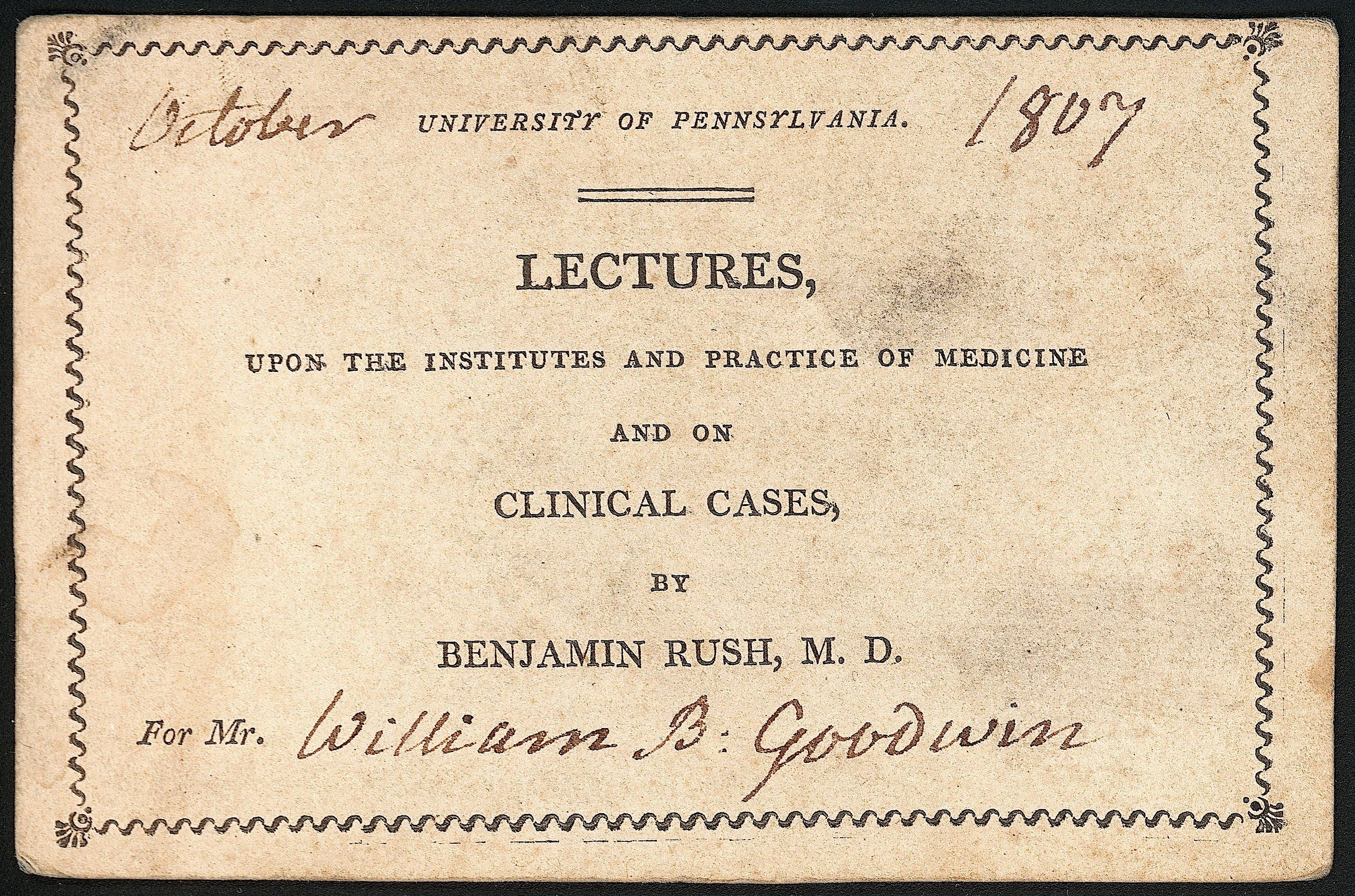

An admission ticket to a lecture given by Benjamin Rush in October 1807. University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Philadelphia. (Public Domain)

Four years later, the hospital placed Rush in charge of all “maniacal” inmates, those suffering from mental disorders and from severe alcoholism. He ordered numerous reforms, ending the public’s pay for view visits, providing stoves for the basement cells, for example, and permitting patients to take walks under the watchful eyes of staff.

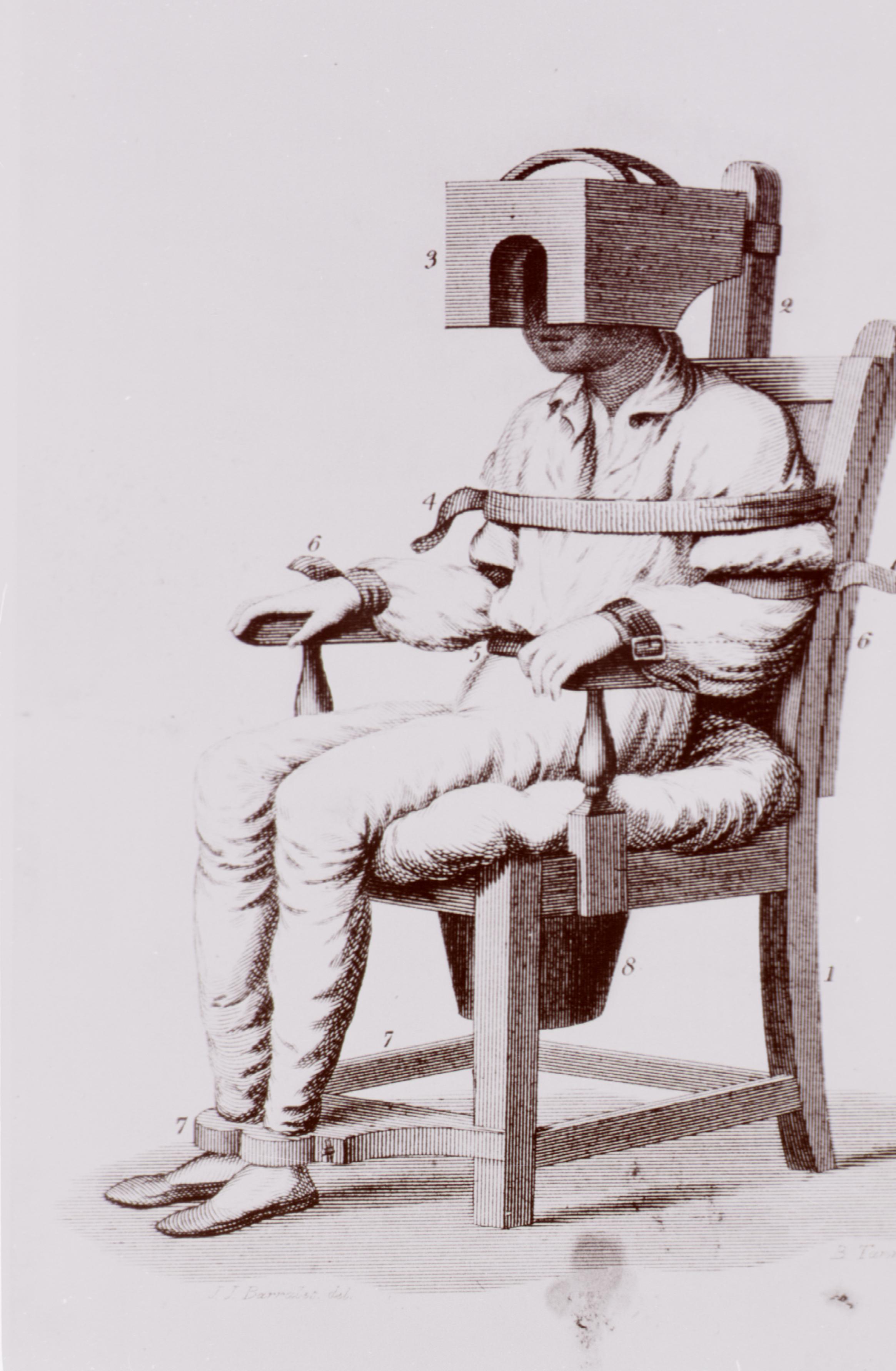

He also experimented with different treatments. He invented a “tranquilizing chair,” designed to calm excessively disturbed patients. They were strapped to the chair with a device of wood partially covering their heads and encouraged to express their emotions without being able to harm themselves or others. He also called for separate wards and special treatments for these patients, and urged the training of physicians to help them in their madness.

An inverted illustration of Benjamin Rush's tranquilizing chair, published in 1811. The National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland. (Public Domain)

Perhaps most significant, Rush recognized the positive effects that sunshine and work had on the mentally ill. He urged fresh air and exercise for his patients, and encouraged them to take up tasks that occupied both their minds and their bodies.

He also stressed that they should be viewed as fellow human beings: “A physician should treat his deranged patients with respect. … Acts of justice and a strict regard to truth tend to secure the respect and obedience of deranged patients to their physician.” Historian Bernard Weisberger found that “Rush even suggested getting the ‘madmen’ and ‘madwomen’ under his care to unburden their distressed minds by writing out their fantasies for discussion, vaguely foreshadowing psychoanalysis.”

Certainly, he saw these patients as treatable, and the staff as more than keepers.

Why We Honor the Physician Today

Frontispiece of “Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon Diseases of the Mind,” 1812, by Benjamin Rush. Internet Archive. (Public Domain)

Rush also remained an advocate of bleeding and purging patients, still a believer in some core cause for all disease. Before condemning Rush for these practices, however, we should heed the words of Dr. Jeffrey Geller, a doctor and professor of psychiatry: “Bleeding, purgation, and so on were simply the best practices of the day, and he believed them to be effective. In 75 years, maybe people will be aghast at how we treat psychiatric patients in 2019. Rush used what was available and sometimes got results.”

Dr. Geller further noted, “Rush’s most important contribution to the development of psychiatry was his attempt to destigmatize people with ‘insanity’ by assuming that their treatment could be hospital based, just as with patients with other illnesses.”

It is for this reason, and for his groundbreaking 1812 textbook, “Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon Diseases of the Mind,” that the American Psychiatric Association in 1965 declared Benjamin Rush “the Father of American Psychiatry.”

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc