On April 5, 1887, Anne Sullivan (1866–1936) wrote a letter to Sophia Hopkins, her friend and patron, about a breakthrough event that had occurred that morning: “We went out to the pump-house, and I made Helen hold her mug under the spout while I pumped. As the cold water gushed forth, filling the mug, I spelled ‘w-a-t-e-r’ in Helen’s free hand. The word coming so close upon the sensation of cold water rushing over her hand seemed to startle her. She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face. She spelled water several times.”

The following day, Sullivan added this postscript: “Helen got up this morning like a radiant fairy. She has flitted from object to object, asking the name of everything and kissing me for very gladness. Last night when I got in bed, she stole into my arms of her own accord and kissed me for the first time, and I thought my heart would burst, so full was it of joy.”

So Sullivan recorded the famous incident that later appeared in Helen Keller’s autobiography, that key moment when a 6-year-old deaf and blind girl had her life transformed by her teacher.

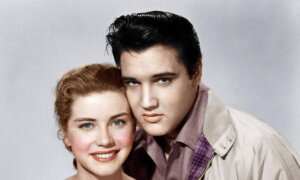

A photograph of Helen Keller at age 8 with her tutor Anne Sullivan on vacation in Brewster, Cape Cod, Mass., in July 1888. (New England Historic Genealogical Society)

A Dickensian Childhood

At age 5, Sullivan had contracted trachoma, a bacterial infection of the eye, and dealt with the damage done to her vision for the rest of her life. But it was there that her similarities to her student ended.

Unlike Helen, whose family was well-to-do, Sullivan was born to poor Irish immigrants in western Massachusetts. Her father was an abusive alcoholic who, after his wife died when Sullivan was 8, deserted his three children. An aunt took in Mary, Sullivan’s younger sister, but she and her brother, Jimmie, were sent to the Tewksbury Almshouse, a disgusting and overcrowded facility for the poor that housed adults and children, including some inmates who were judged insane. Her frail brother died within three months of their arrival, likely from tuberculosis, and Sullivan lived alone in misery for the next two years.

In 1877, following an investigation of conditions at the Almshouse, Sullivan spent a short time working with nuns in the Lowell hospital. Against her wishes, she was then transferred back to Tewksbury, though this time she was placed in a ward with single mothers and pregnant women. By then, she’d heard of schools for the blind, and when the Massachusetts State Inspector of Charities visited, she sprang before him and dramatically declared, “Mr. Sanborn, I want to go to school!”

Rising Up

The courage she displayed that day paid off.

In October 1880, Sullivan entered the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown. During her first two years, she was a bad fit with the other students, who considered her rough-mannered and easily riled. In a letter written eight years later to Sophia Hopkins, Sullivan thanked her former cottage mother for “the mother-love you gave me when I was a lonely, troublesome schoolgirl, whose thoughtlessness must have caused you no end of anxiety.” In this same letter, she recollected her “quick temper and saucy tongue” from those schooldays.

Others at the school, like Laura Bridgman, who was Perkins’s first graduate, and several teachers, also took Sullivan under their wing. Between their coaching and her own determination to succeed, she became class valedictorian.

During her address at graduation, Sullivan concluded: “Duty bids us go forth into active life. Let us go cheerfully, hopefully, and earnestly, and set ourselves to find our especial part. When we have found it, willingly and faithfully perform it; for every obstacle we overcome, every success we achieve tends to bring man closer to God and make life more as He would have it.”

The Howe Building at the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Mass., in 1912. (Public Domain)

Adherence to this credo and Sullivan’s impressive record as a student accounted for her first post after graduation. When Arthur Keller of Tuscumbia, Alabama, contacted the school in hopes of finding a tutor for his young daughter, the school’s director, Michael Anagnos, immediately recommended Sullivan.

Soaring High

Though she was frightened that day when she stepped from the train into a culture far removed from New England’s, Sullivan nonetheless later recalled, “I felt that the future held something good for me.” She could scarcely have imagined that this future would include half a century serving as a teacher and companion to the wild, sightless child she met that day, that the two of them would soon gain worldwide renown, and that one day this same companion would hold her by the hand when Sullivan died.

By May 1888, only some 15 months after Sullivan’s arrival in Tuscumbia, both she and Helen were gaining renown around the country for their leaps forward in Helen’s learning. That year, Sullivan, Helen, and Mrs. Keller traveled to Washington, where they met again with Alexander Graham Bell and, for the first time, with President Grover Cleveland. In Boston, where Sullivan and Keller were greeted with great acclaim, Michael Anagnos convinced the Kellers to enroll Helen in the Perkins School with Sullivan as her guide and mentor.

Anne Sullivan is a fascinating example of the many influences that go into the building of character. Her harrowing younger years of abuse, pain, and loss; the education, love, and refinement she received during her Perkins schooling; and the faith in her abilities shown by her teachers—all of these shaped the young woman who was given charge of Helen Keller.

It was only a short time later that Mark Twain met Helen, and the two became fast friends. He also marveled at the accomplishments of her young teacher, and it was Twain who first referred to Anne Sullivan as a “miracle worker.”

Anne Sullivan Memorial in Feeding Hills, Massachusetts. (<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Sullivan#/media/File:Anne_Sullivan_Memorial.jpg">Neville2023/CC BY SA 4.0</a>)

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc