LOS ANGELES—When students in Jamie Rector’s Energy and Civilization course at the University of California–Berkeley came to him with the idea for a project on California’s abandoned oil wells, he was intrigued.

The state has more than 120,000 abandoned oil and gas wells, as well as 30,000 idle wells and 70,000 active wells. Many were drilled or dug in the late 1800s, clustered in areas such as downtown Los Angeles and near present-day Dodger Stadium, where the California oil boom began.

The concern among some is that these wells might be emitting methane or other hydrocarbons. Older ones are likely to have been improperly or shallowly sealed.

The federal government has spent $4.7 billion to plug and reclaim abandoned wells. California has plugged about 1,400 wells at a cost of $29.5 million since 1977, and now requires operators to eliminate idle wells or face increasing fees.

As they researched California’s abandoned oil wells, Rector’s students discovered an abundance of natural oil seeps located above the same fields—and came to a surprising conclusion. According to them, geologically driven, natural oil seeps are a major contributor to California’s greenhouse gas emissions. And drilling—long seen as the problem, not the answer—might be a panacea for emissions.

Natural seeps occur when liquid oil and gas leak to the Earth’s surface, both on land and under water. California sits on actively moving tectonic plates, which create fractured reservoirs and pathways for the oil to escape.

Waters off Southern California are rife with seeps, and oil and gas fields, including the Salt Lake field beneath the La Brea Tar Pits, and the Coal Oil Point field off the coast of Goleta, have some of the highest natural hydrocarbon seep rates in the world, emitting gases such as methane, as well as toxic volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

But these geologically driven seeps, Rector said, have been largely unaccounted for in assessing how oil production fields contribute to California’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“There are hundreds of studies linking oil and gas fields to greenhouse gas emissions, to cancer rates, to climate justice, to groundwater pollution and everything else,” said Rector, a professor in the University of California–Berkeley’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department. “And yet none of these studies ever considered the possibility that it wasn’t from equipment or production, but natural seeps above the oil fields.”

Reviewing existing literature, Rector’s team calculated that natural seeps, together with orphaned wells, produce 50 times more methane emissions than oil and gas equipment leaks in Southern California.

If seeps are driving emissions above oil fields, Rector said, then plugging abandoned wells may do little to help pollution.

In fact, he said, the only demonstrated way to reduce natural seep emissions is by depleting underlying reservoirs—that is, by drilling.

A tar seep from oil deposits is seen at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles on July 30, 2025. University of California–Berkeley professor Jamie Rector said that because of California’s geological characteristics, natural oil seeps contribute significantly to its greenhouse gas emissions. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Pointing to studies showing that oil production has reduced and even eliminated seeps, he suggested that California’s current regulatory environment may be counterproductive.

“The crazy thing is, by stopping oil and gas production in California, after we’ve regulated and really gotten equipment emissions way down, we may be increasing seep emissions,” Rector said. “Because these seeps come up through the oil and gas fields, and the only way to stop it is by producing oil.”

Ira Leifer, a researcher in the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of California–Santa Barbara, said the argument is valid but that Rector’s analysis gets ahead of available data.

“The problem is that there is no statewide seep emissions estimate,” said Leifer, who studies marine seeps and oil field emissions. Arriving at a publishable estimate is “impossibly difficult,” he said.

Rector characterized the student project as a “skunkworks” effort without any funding, which he said he planned to submit for peer-review by August. Ideally, it will be followed by field research.

“We will have to go out and make measurements with the hypothesis that seeps are the principal cause rather than oil field equipment, and make measurements along traces of faults, above oil fields where faults intersect the surface,“ he said. ”That’s really the only way we’ll get to the bottom of this.”

Meanwhile, Leifer is working on his own forthcoming paper analyzing satellite data of methane anomalies. The strongest ones, he said, are associated with refining and other large infrastructure, and with natural faults that have been punctured by man-made wells—something he calls “anthropogenically amplified seepage.”

Of Rector’s paper, he said: “I fundamentally agree with their conclusion. I just don’t think it can be supported with data at this point.”

Leifer acknowledged that petroleum-related hydrocarbon emissions, including a “poorly understood” geological component, “clearly are extremely significant to overall California methane budget emissions,” based on spatial patterns from satellite data he has been studying for years.

Both Leifer and Rector agree that so far, emissions from orphaned wells and natural seeps have not been differentiated. Thus, the critical question remains unanswered: How much does natural seepage contribute to overall emissions?

While California has some of the highest concentrations of recoverable oil and gas in the world, it also boasts the most stringent oil and gas regulations in the country, and production has been in steady decline as the state aims for a 2045 “decarbonization” goal.

Some pumpjacks operate while others stand idle in the Belridge Oil Field near McKittrick, Calif., on Nov. 3, 2021. California has more than 120,000 abandoned oil and gas wells, plus 30,000 idle wells. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

“If we’re really worried about emissions, pollution, disadvantaged communities, health—even fire danger, earthquakes and public safety—this is all affected by seeps,” Rector said.

By relying on studies that have broadly ignored them, he said, policymakers may have unknowingly implemented counterproductive policies.

Ancient Rocks, Modern Problems

Los Angeles sits atop one of the most petroleum-dense basins on the planet. Rector cited a 2015 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) study estimating that there are still 1 billion barrels of recoverable oil in the Los Angeles Basin. This year, the USGS estimated that 61 million barrels of recoverable oil and 240 billion cubic feet of gas remain.

The organic-rich sediment beneath us is oil-prone and “relatively immature,” Rector said, and hydrocarbon generation is ongoing. Massive natural seeps such as Coal Oil Point off the coast of Santa Barbara, California—one of the largest seep fields in the world—continue to actively produce petroleum.

Seeps concentrated along the coast are fed by adjacent reservoirs deep within sedimentary rock beneath the region’s oil and gas fields.

California’s geology is also uniquely affected by actively shifting tectonics. Along with organic-laden sediment deposits, the shifting plates create conditions for rich petroleum accumulations, as well as natural seepage and hydrocarbon venting, Rector said.

Oil fields both in the Los Angeles Basin and throughout Southern California, he said, tend to concentrate along fault lines, allowing oil generated down deep to migrate into shallower pools and eventually make its way to the surface.

The La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles is one of the largest seepage sites in the state, and hydrocarbon gas emissions there are the highest on record for any onshore seepage site in the United States, according to a 2017 research article published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

California’s bubbling tar pits have been part of human culture for millennia, their bitumen used by the Chumash Tribe as a sealant long before anyone showed up to drill for oil.

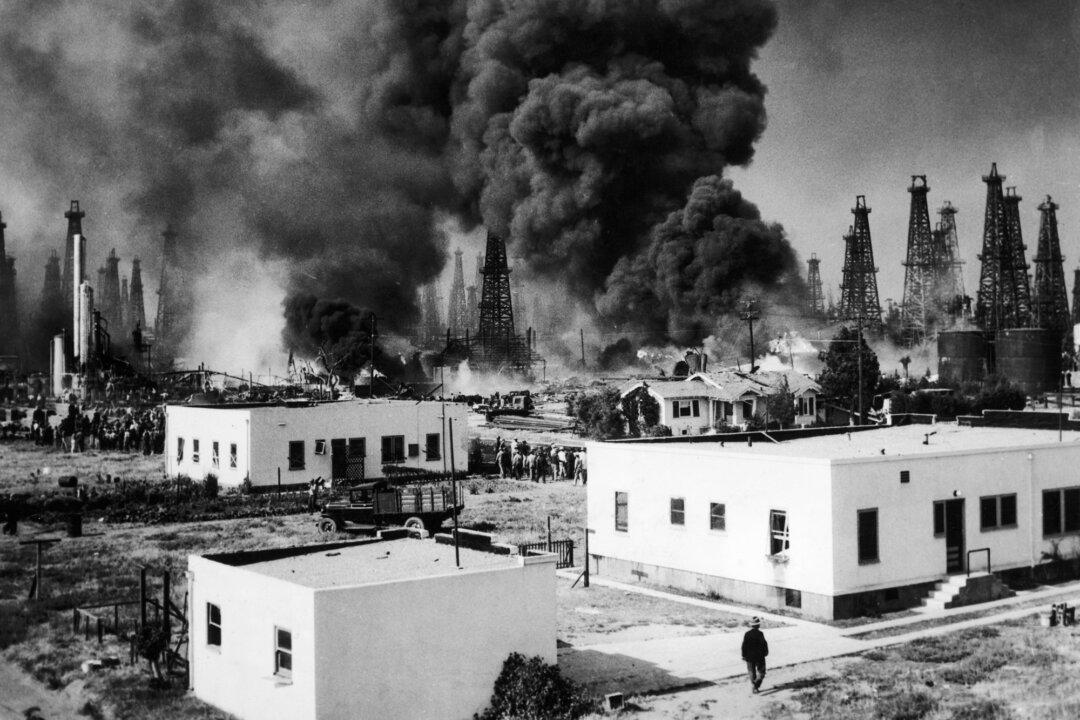

When they did, in the late 1800s, surface seeps and methane vents played a crucial role in the California oil boom, during which most of the state’s large oil fields were discovered, starting with the Los Angeles Oil Field.

“Back a hundred years ago, they had people, they were called ‘smells,' and they would smell the ground trying to see if there were oil seeps in an area,” Rector said, describing how early oil pioneers would decide where to dig.

An explosion and resultant fire on the Signal Hill Oil Field threatens nearby homes, in Long Beach, Calif., in June 1933. (FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

More recently, trapped oil and methane have offered a pointed reminder of the city’s ancient subterranean history, including the mysterious 1985 explosion at a Ross Dress for Less store near the La Brea Tar Pits that sent 23 people to the hospital.

In a report the same year, a city task force noted that the source of the explosion was likely natural seepage of methane gas.

Oil production in Los Angeles County has declined dramatically since its peak in the 1920s, when it was one of the most prolific producers in the world.

But the infrastructure left in place—and whatever interaction it may have with naturally occurring seeps—remains vast and, in some ways, hidden in plain sight.

Health Impacts

In a 2023 paper exploring health impacts of oil and gas facilities on “cumulatively burdened” communities in Los Angeles County, researchers point to this hidden infrastructure.

“As government and industry negotiated to continue oil drilling within residential zones, oil extraction in L.A. County became increasingly hidden from public view, often by utilizing tall walls or hedges, and consolidating operations into fewer neighborhoods,” the authors and university researchers wrote.

Production may have declined, but the county remains one of few places in the country where extraction occurs in densely populated communities: More than 500,000 residents live on blocks within one kilometer of an active or idle well, according to the study.

Jill Johnston, associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at the University of California–Irvine and a co-author of the 2023 study, was part of a panel assembled by the California Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM) to review epidemiological research on oil and gas in the state.

What the panel found was “very strong evidence” of an association between adverse birth outcomes and respiratory symptoms for people living in proximity to oil and gas production.

“There were a sufficient number of studies, and consistent results, that we felt we would have a high confidence in a causal relationship,” Johnston told The Epoch Times.

That review, she said, led to the introduction in 2023 of a statewide 3,200-foot buffer zone between new oil and gas wells and “sensitive receptors” such as homes and schools.

Researching communities in South Los Angeles, Johnston looked at respiratory health and lung function, finding deficits among people living closer to the wells.

She also looked at weight and blood pressure and tested for toxic metals, finding nickel and manganese clustered together in people living close to wells, a potential indicator of exposure to crude oil.

A tar seep from oil deposits is seen at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles on July 30, 2025. The site is one of the largest seepage sites in California and has the highest hydrocarbon gas emissions on record for any onshore seepage site in the United States, according to a 2017 research article. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Untangling Sources

In work associated with the University of Colorado, Johnston’s team installed air monitors in South Los Angeles communities to measure for methane and other hydrocarbon emissions.

According to Johnston, in these communities that are surrounded by freeways and already overburdened with pollution sources, her aim was to try to figure out what pollution was coming from the wells as opposed to “normal” traffic.

“By measuring these different gases, we were able to pick out a methane-related signal that we could attribute to the oil and gas production and not traffic,“ she told The Epoch Times. ”And we saw some of those concentrations were the highest about 500 meters from the well.”

When measuring health impacts of oil and gas emissions, methane is used as a kind of proxy for other VOCs: Where methane is found, there are likely to be toxic or hazardous gases.

Johnston said the question of seeps has rarely come up in conversations with regulatory agencies.

“Because there are still so many active wells, generally the priority has been around trying to collect and characterize what’s happening around those sites,” she said.

Even if it was possible to differentiate the contribution of seeps to hydrocarbon emissions, Johnston said, she does not expect that it would change the conversation much about epidemiological impacts.

“Maybe it would be more relevant to understanding greenhouse gas emissions, but the impact on people’s health is kind of the same, it’s just about proximity to these fields,” she said.

She noted that most studies on public health impacts are based on drilling permit records.

“If seeps overlap with where there’s active drilling, it will be hard to disentangle those things,” she said.

The same issue applies to older, improperly sealed wells. Johnston said that although these wells may be producing emissions, most are in places where there is also active drilling.

Oil production in Los Angeles declined in the ’90s and began to ramp up again in about 2010. Johnston said this triggered an interest in these hidden wells, as residents noticed odors and became aware of the drilling sites.

Today, she said, Los Angeles’s wells are generally very old and not very productive. Land use ordinances that will ban drilling entirely in the city and county are expected to be finalized soon.

Oil pumps operate in the Los Angeles area on July 30, 2025. Los Angeles County is among the few places in the United States where drilling occurs in densely populated areas, raising health concerns for residents. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Rector acknowledged that his paper does not change Johnston’s results.

“Yes, above oil and gas fields, people get asthma, they get higher incidence of hypertension, more heart disease, more leukemia, other cancers, and it’s pretty compelling data,” he said.

“But the fundamental question is, is it really the wells and the operations, or the seeps?”

According to Rector, it is likely a combination of both.

“But according to our studies, [oil production emissions] are trivial compared to seeps,” he said.

Production Versus Natural Seeps

Experts tend to agree that estimating seep emission rates is extremely difficult, especially in a large area where emissions are diluted in the atmosphere.

But John Harris, an energy industry professional with a background in petroleum geosciences, said that in theory, an estimate should be straightforward.

“It’s basic physics,“ said Harris, who is president of Numeric Solutions LLC, a geosciences management company. ”You have oil and gas migration and entrapment in the Los Angeles space, and you understand the position and character of the faults.”

Oil and gas accumulations have been mapped since the late 1800s, he said, and the geology is well-understood. While CalGem has not updated its seep maps since the 1980s, he noted that USGS has done extensive mapping, as have the state of California, third parties, and academia.

CalGEM did not respond to an inquiry from The Epoch Times.

Rector’s team, Harris said, needs to understand the intersection of these accumulations, which have leak pathways and faults or fractures leading to the surface, and the pressures they are under.

Citing a draft of the pre-print, he said, “I’d like to see a bit more math.”

Comparing “top-down” and “bottom-up” estimates, Rector concluded that the amount of emissions from equipment-related methane and VOC leaks at oil and gas facilities in Southern California is low compared with the amount that emanates from natural seeps and orphaned wells—estimated at 504,000 kilograms per day, plus or minus 148,000 kilograms.

This dwarfs estimates for equipment-related emissions, which the paper suggests may have dropped substantially in the past decade or so, to less than 10,000 kilograms per day.

In a 2020 report, the California Energy Commission concluded that there was little evidence for extensive leakage from the state’s plugged and abandoned wells. However, researchers acknowledged that the sample “may not represent most abandoned and plugged wells that are primarily located in active major oil and gas fields.”

According to Rector, government-led measurements of oil and gas equipment emissions have been overestimated. He pointed to the fact that abandoned, idle, and improperly sealed wells are also known to contribute fugitive emissions near oil and gas fields.

A crew plugs one of a total of 56 abandoned oil wells at the Placerita Oil Field in Santa Clarita, Calif., on Feb. 22, 2022. The state has spent millions of dollars since the late 1970s to plug some of them. Nationwide, the federal government has spent $4.7 billion to plug and reclaim abandoned wells. (Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images)

There are tens of thousands of such wells in Southern California and older ones are likely to be leaky, the paper argues, becoming “anthropogenic macro-seep locations” that should be added to the natural seep inventory.

Either way, Rector said, the remedy is the same: The only proven way to reduce seep emissions is by depleting the underlying oil field.

‘Not a New Concept’

The idea that drilling can reduce emissions from seeps is not new, Harris said, although doing so “at a larger scale and in a dense urban area where there’s a general anti-oil-and-gas sentiment” is novel.

James Boles, professor emeritus of earth sciences at the University of California–Santa Barbara, has studied offshore seeps that produce some of the highest seep rates in the world.

In a 2023 paper published in Marine and Petroleum Geology, he analyzed data from two 900-square-meter steel tents installed by ARCO near its offshore platform off the coast of Santa Barbara to capture natural seafloor methane seepage.

Over time, the tents, installed in the 1980s, showed a reduction in methane seepage correlated to oil production, a phenomenon observed on land seeps in places such as Iraq for decades.

More dramatic was the installation of a new well directly beneath the tents: Within weeks of turning it on, more than three decades of natural methane seepage captured by the tents simply stopped.

The ARCO tents, Boles told The Epoch Times, are “the best evidence” that oil production can affect natural seeps.

“Over time you could see the seeps gradually go down,“ he said. ”But just in 2013, Venoco, which [operated] that field, drilled a single well and it killed all the seeps in two weeks.”

Even with that obvious correlation, he said, reception was refracted through political sensitivities.

“People from local air quality boards, and for a long time in the newspapers, reporters, they argued that there are no relationships between natural seeps and oil fields and oil production,” Boles said. “That’s just not true.”

Anecdotally, as a longtime resident of the area, Boles observed that seeps have come back as offshore platforms have shut down.

“I’ve noticed on the backside of Santa Cruz Island, for example, there’s tar that shows up on those beaches that wasn’t there before,” he said.

Oil pools along a hillside in rural Ventura County, Calif., on Aug. 2, 2025. (Courtesy of Judson Baker)

One thing he found “rather cavalier” in Rector’s study, he said, was an estimate of cumulative emissions for Southern California that assumed that Ventura and Santa Barbara counties are comparable to the Los Angeles Basin.

If anything, Boles said, that is a very conservative estimate.

“Probably there are more seeps in the Santa Barbara Basin than the LA Basin,“ he said. ”The Coal Oil Point area, that’s long been known to be a really extreme area.”

Atmospheric Versus Geological Science

In California, more than half of methane emissions come from agricultural production, according to the California Air Resources Board. The rest come from landfills, fugitive emissions from oil production, and industrial operations, according to the state, which in recent years has deployed increasingly sophisticated tools to detect methane hotspots and leaks—including airborne remote sensing and a $100 million satellite program.

Rector said studies on methane emissions from oil and gas operations are rarely able to identify the source in individual pieces of equipment.

“It turns out all these remote measurements. ... They can allocate emissions to an oil and gas field, but not to individual points, like individual pieces of equipment or individual seep positions,“ he said, noting that smaller seeps with continual emissions are especially difficult to detect. ”So they’ll mix all these together.”

The geological component, he said, is often poorly understood or simply unaccounted for. He maintains that seep emissions, whether natural or attributed to orphaned wells, are related to the reservoir volume beneath them.

“Throughout the world and in Southern California, they’re seeing huge emissions from oil fields, but because it’s atmospheric science and not geological science, [seeps are] completely ignored,” he said.

He said he hopes that the paper will prompt a new generation of research that fills in the blanks.

According to Rector, if seeps are as bad as they appear, and we have already regulated wellhead emissions, then we should be asking why oil and gas production is a problem.

“Why are we so freaked out?” he said.