A few years after winning the Revolutionary War, America’s Founding Fathers crafted and ratified a constitution—guaranteeing rights, liberties, and freedoms—that remain in effect today. Was this the result of luck? Or was it the product of visionary leaders who served where they were best suited—moral men of character, humility, and conviction, who sought God’s guidance and pledged their lives, fortunes, and honor to the cause?

The answer becomes clearer when the choices they made are considered.

Nominating a Founder, Organizer, Strategist, and Visionary Leader

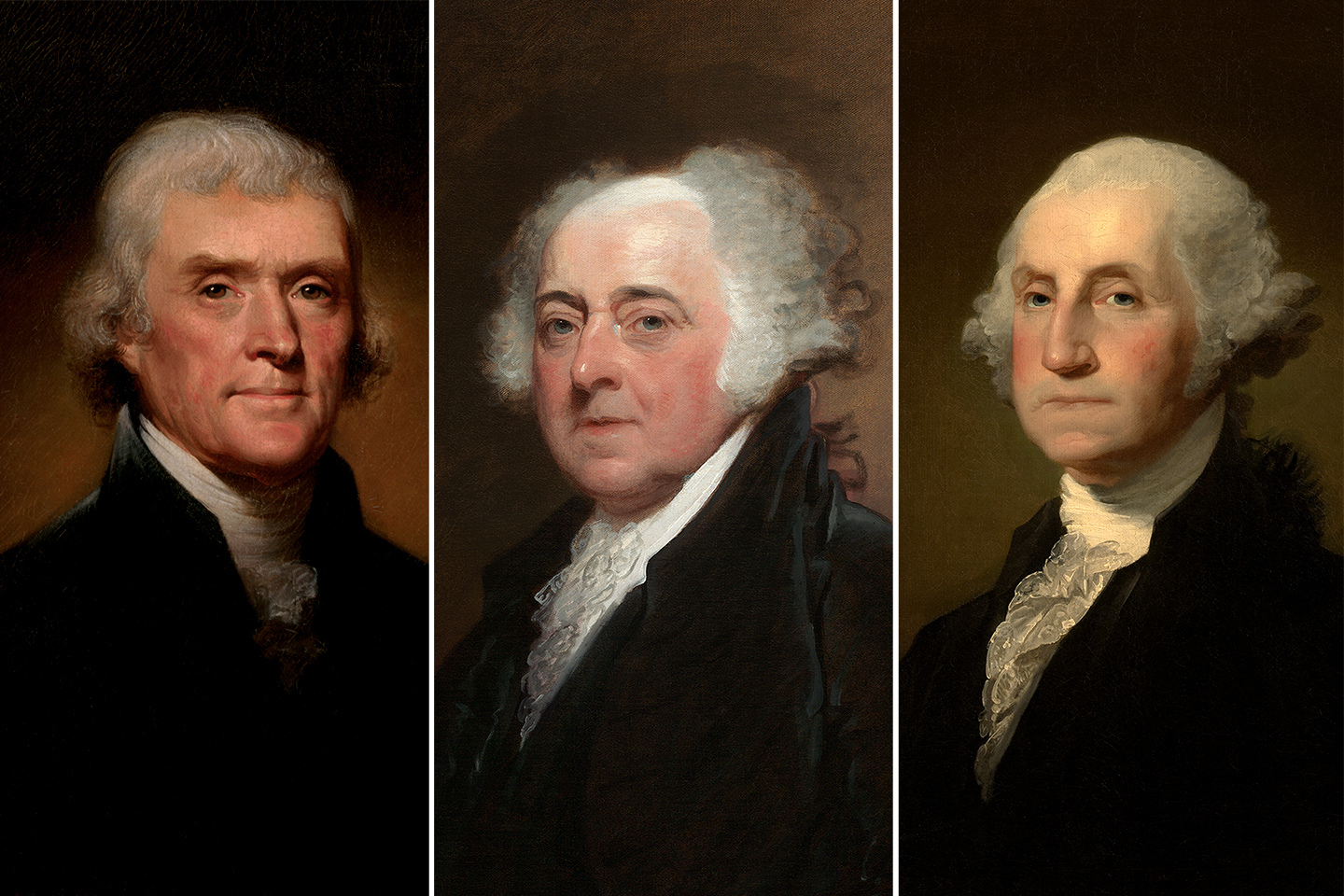

"Washington, Appointed Commander in Chief," 1876, by Curier and Ives. Library of Congress. (Public Domain)

On a cool Friday June morning in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress met in the Pennsylvania State House—today known as Independence Hall. Most of the delegates were pleased when John Hancock, president of Congress, announced the man chosen to serve as “General and Commander in Chief of the Army of the United Colonies.” One delegate from Virginia, however, was less than pleased—for it was he who had been chosen.

Just two days earlier, on June 14, 1775, Congress had created the Continental Army to command the forces besieging British-held Boston after the battles of Lexington and Concord. In a show of unity, soldiers from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia were ordered to march to Cambridge and join the siege. That decision left Congress with a pressing question: Who should command this new army?

Several names surfaced. Charles Lee, an ambitious former officer of the British Army, boasted the strongest military résumé, though he wasn’t born in the colonies. Artemas Ward and John Hancock of Massachusetts Bay were also considered. Yet the fight in Boston was not just New England’s—it was a struggle for all Thirteen Colonies. To unite them, it was essential that the commander come from outside Massachusetts Bay. Virginia, the most populous colony, offered the best chance for consensus. A Massachusetts Bay delegate who was a colleague of both Ward and Hancock found the ideal candidate in Col. George Washington.

George Washington: A Sense of Duty

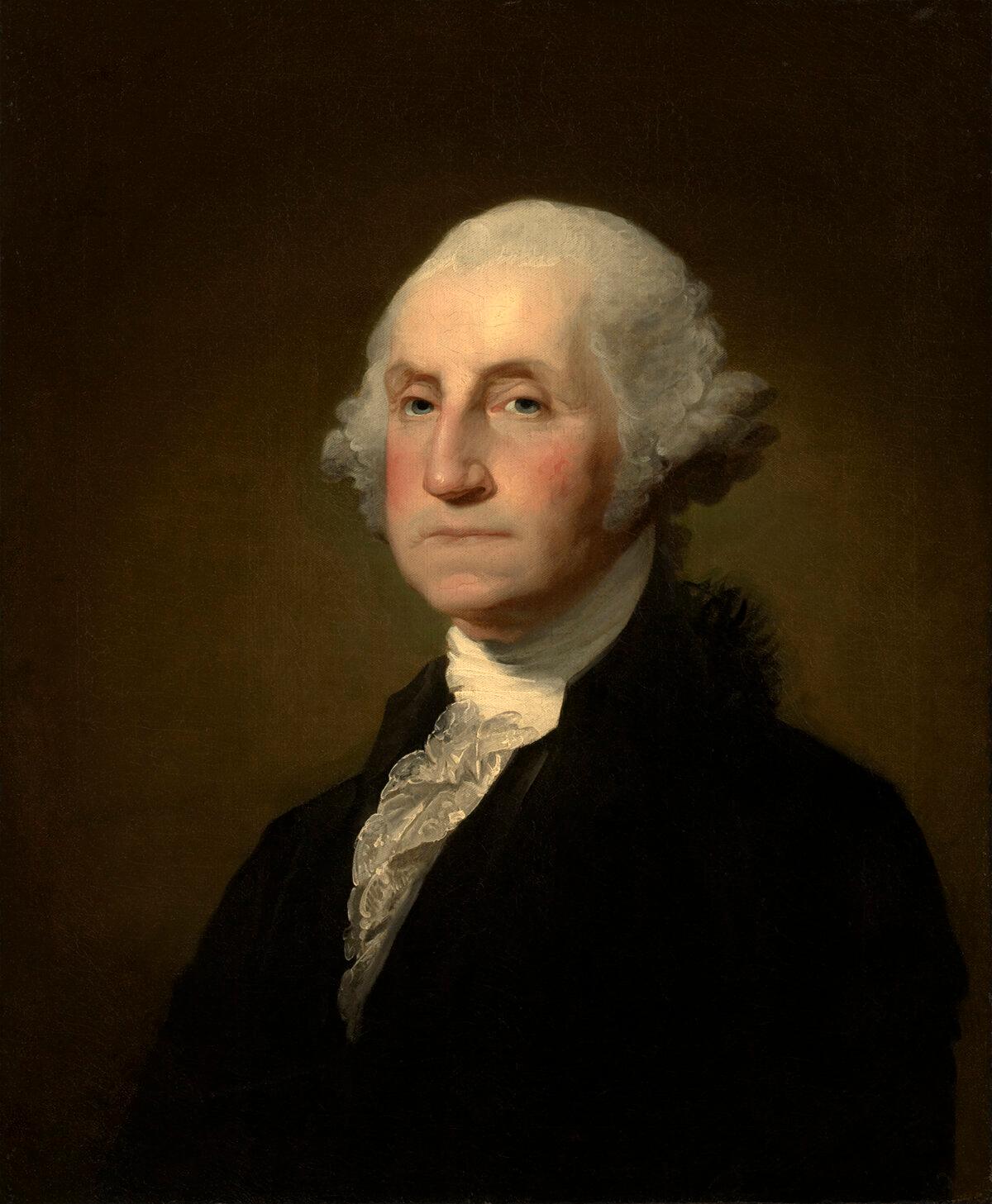

A portrait of George Washington, 1803, by Gilbert Stuart. Oil on canvas. Clark Art Institute,<br/>Williamstown, Mass. (Public Domain)

A veteran of the French and Indian War, Washington attended Congress in his military uniform, projecting “martial dignity,” an “elegant form,” and “great self-command.” Dr. Benjamin Rush later observed, “You would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand men.”

When nominating Washington, the Massachusetts Bay delegate declared, “I had but one Gentleman in my Mind for that important command and that was a gentleman from Virginia who was among Us and very well known to all of Us, a Gentleman whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great Talents and excellent universal Character would command the Approbation of all America, and unite the cordial Exertions of all the Colonies better than any other Person in the Union.”

Washington had likely expected to serve only as a general, not to oversee the entire war effort. It was a role he had not sought and did not desire. Upon realizing he was the nominee, Washington modestly slipped away. His humility only strengthened support for his candidacy, and, the next day, Congress unanimously appointed him commander in chief.

Honor and duty outweighed his reluctance and desires. Rising before Congress on that cool Friday morning of June 16, Washington confessed: “Mr. President, Tho' I am truly sensible of the high Honour done me in this Appointment, yet I feel great distress, from a consciousness that my abilities & Military experience may not be equal to the extensive & important Trust.”

He pledged obedience to civilian authority: “However, as the Congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous duty & exert every power I Possess in their service & for the support of the glorious Cause.”

With humility, Washington added, “But lest some unlucky event should happen unfavourable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every Gentn in the room, that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think my self equal to the command I am honoured with.”

Declining a salary, Washington asked only to be reimbursed for expenses at war’s end. In a letter to his wife Martha, he assured her that, “So far from seeking this appointment, I have used every endeavour in my power to avoid it … from a consciousness of its being a trust too great for my Capacity. … I shall hope that my undertaking of it, is designd to answer some good purpose.” He continued by placing his reliance on God: “That Providence which has heretofore preservd, & been bountiful to me, not doubting but that I shall return safe to you in the fall.”

Perseverance

Postage stamp marking Washington's evacuation of his troops in New York. (Public Domain)

During the war, Washington’s courage and moral character were never questioned, but his leadership was as military losses mounted. Friends like John Adams turned against him, while rivals Charles Lee and Horatio Gates schemed to replace him. Yet when things were at their darkest, Washington’s actions proved his detractors wrong.

After a crushing defeat on Long Island left his army trapped in Brooklyn, New York, Washington remained composed and expressed no fear. He calmly organized an evacuation and insisted on being the last man to leave. When the war seemed lost, Washington planned for a daring raid in Trenton, New Jersey. While battered by a winter storm, Washington personally led his men across the ice-choked Delaware River before marching towards the enemy. In battle after battle, Washington led by example by placing himself in the line of fire to rally his frightened men. He listened to his officers’ advice, prayed to his heavenly father, and carried burdens far heavier than ordinary men could reasonably bear.

Through determination, perseverance, and faith, Washington led the Continental Army to decisive victory at Yorktown, Virginia, securing our nation’s independence against impossible odds.

Humility

Washington’s appointment as commander in chief proved pivotal for the future of the United States in ways few imagined in 1775. His leadership, moral character, perseverance, and courage made him the indispensable man of the Revolution.

When the war ended, Washington stood at another crossroad. He could have seized absolute power as previous conquerors had done, but he chose not to. Instead, on Dec. 23, 1783, he resigned his commission before Congress and quietly returned to Mount Vernon as a private citizen. In his 1796 Farewell Address, after having served as president for two terms, Washington relinquished power again by declining to run for a third.

Washington’s initial appointment as commander in chief would not have been possible without the foresight of another Founding Father: John Adams, the Massachusetts Bay delegate who placed his name before Congress and helped unite the colonies under his command.

John Adams proposing George Washington for commander in chief of the American Army. Library of Congress. (Public Domain)

John Adams: Holding to Principles

John Adams was deeply influenced by great thinkers such as John Milton, Seneca, Cicero, and Aristotle, as well as mentors like James Otis Jr. and his wife, Abigail. As a young attorney in Boston, Adams was determined to practice law in accordance with his principles. His convictions were put to the test on the winter night of March 5, 1770, when British soldiers opened fire on Bostonians in what became known as the Boston Massacre.

The city erupted in rage, and no lawyer dared defend the soldiers and their commanding officer, Capt. Thomas Preston, after their arrest. Adams, however, firmly believed in the right to counsel, the presumption of innocence, and that all defendants were entitled to a fair trial. Willing to risk his career and reputation, he stepped forward to defend the soldiers, assisted by fellow patriot Josiah Quincy Jr.

Facts Above Passions

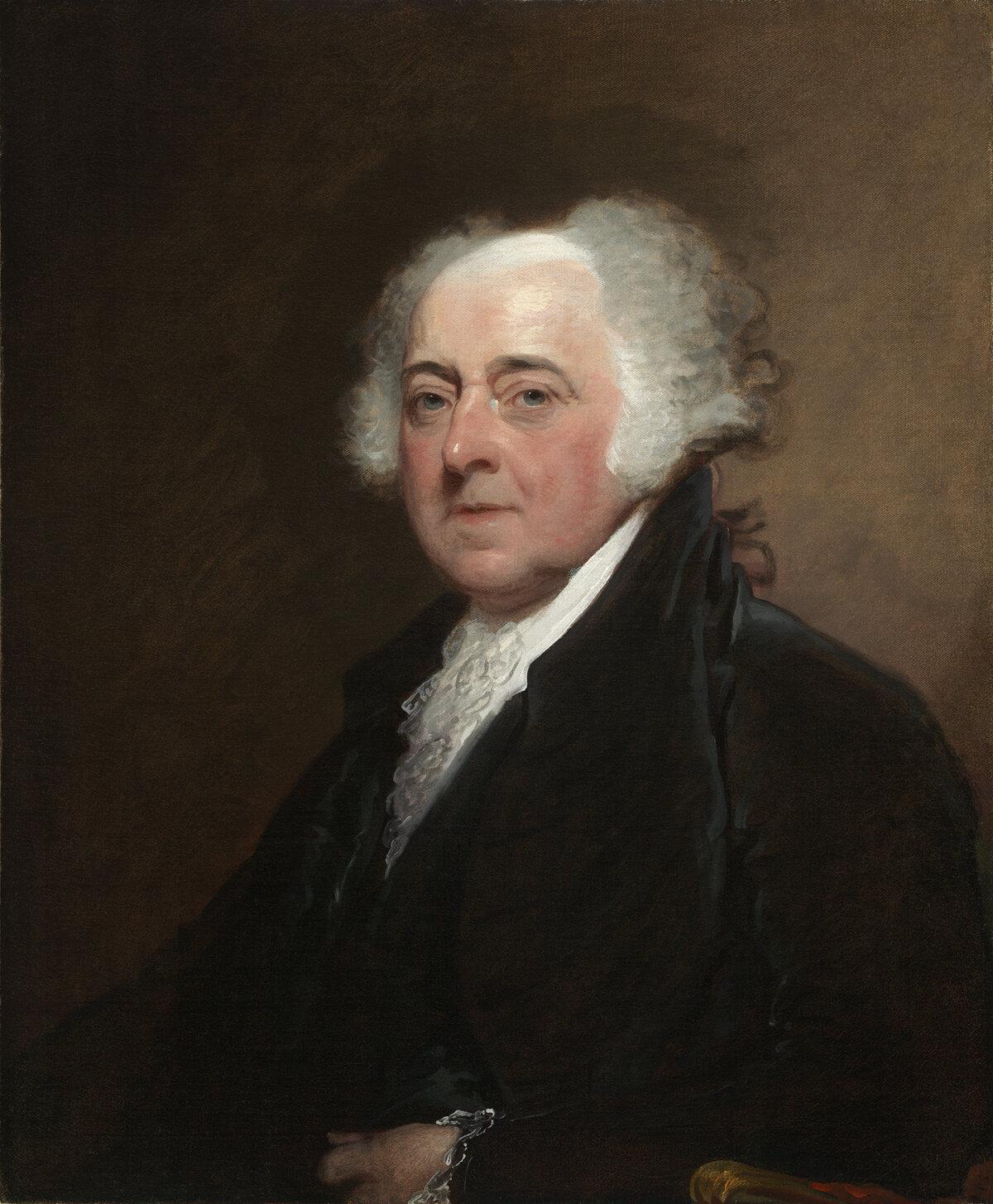

A portrait of John Adams, circa 1800–1815, by Gilbert Stuart. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. (Public Domain)

John Adams arranged for Capt. Preston to be tried separately from his men, allowing him to pursue different legal strategies. In the first trial, Preston was accused of ordering his men to fire. Adams and Josiah Quincy argued that conflicting witness testimony failed to prove that Preston issued such an order. He acknowledged the public’s desire for punishment but reminded the jury that “facts are stubborn things, and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” Preston was acquitted, though Adams endured bitter criticism in the press.

In the second trial involving the soldiers, Adams argued self-defense, tweaking Sir Edward Coke’s principle that “a man’s post, like his house, is his castle.” The jury acquitted six soldiers, convicting only two for manslaughter.

Adams demonstrated—to his detractors in London and, more importantly, to posterity—that in America, even the most despised enemies could, and should, receive a fair trial. Unfortunately, his law practice suffered, as many clients abandoned him, but he found consolation in the words of Cesare Beccaria, whom he quoted during the trial: “If, by supporting the rights of mankind, and of invincible truth, I shall contribute to save from the agonies of death one unfortunate victim of tyranny, or of ignorance, equally fatal, his blessings and tears of transport will be sufficient consolation to me for the contempt of all mankind.”

Thomas Jefferson: Moral Courage

A portrait of Thomas Jefferson, 1800, by Rembrandt Peale. Oil on canvas. White House, Washington. (Public Domain)

Though a slaveowner, Thomas Jefferson called slavery a “moral depravity,” contrary to natural law, and a threat to the American cause. Taking a risk to his reputation and political future, he condemned the institution of slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence—a bold move considered a radical act decades before the abolitionist movement. Jefferson hoped that reason would gradually put an end to the practice.

Although his denunciations of the slave trade were stricken from the final version, Jefferson’s inclusion of “All men are created equal” was later used to ensure its eventual destruction. It resonated across time.

At this time, however, there were other issues to consider. As John Hancock signed the final draft of the document establishing our great nation, Gen. George Washington and the Continental Army faced the daunting task of defending it against the might of the British Empire.

Our Founding Fathers were far from perfect. They were flawed men who often stumbled while wrestling with doubts and contradictions. But their humility, principles, and moral courage laid the foundation for a nation striving to form “a more perfect union.”

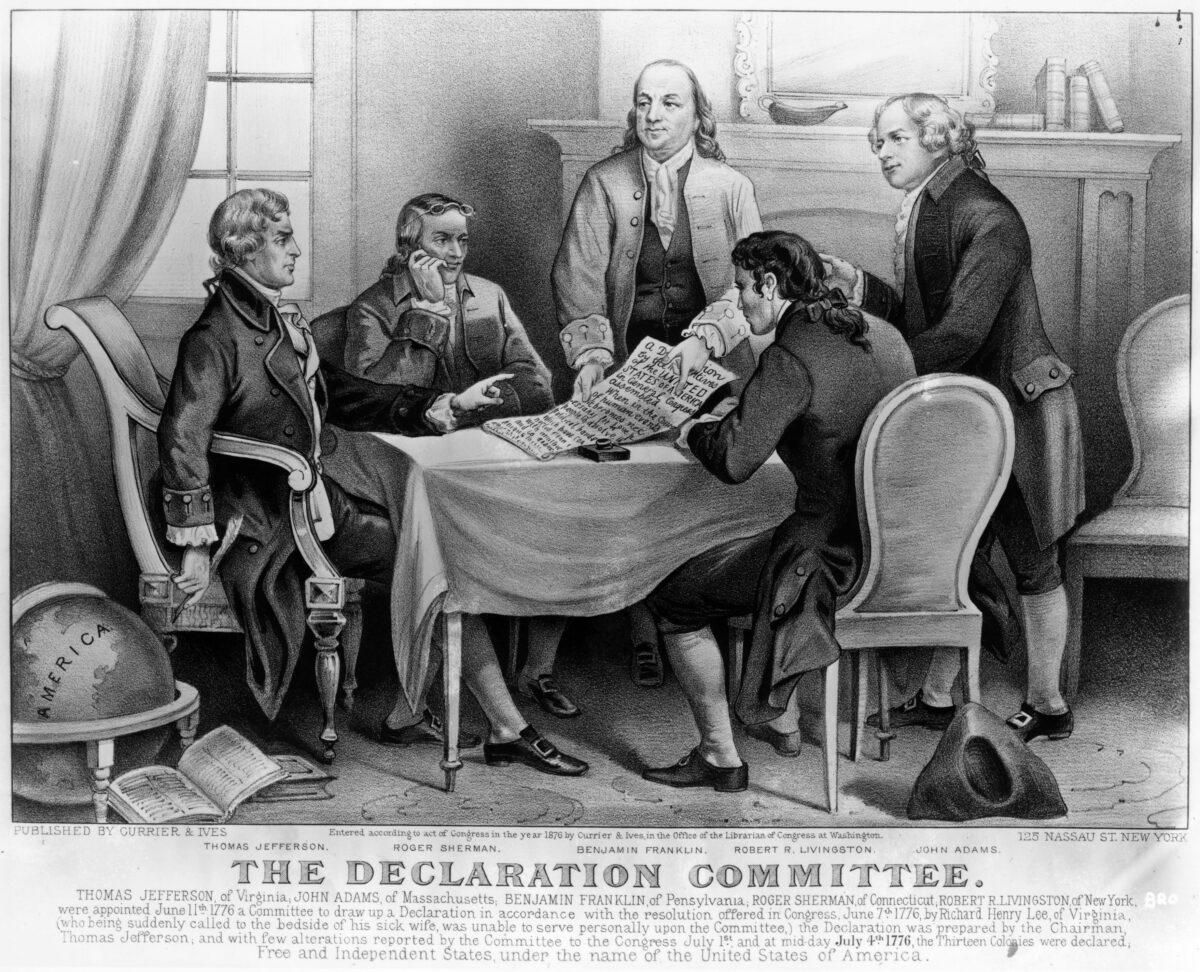

The committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. (L–R) Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, and John Adams. (MPI/Getty Images)

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc