California is the nation’s undisputed leader in agricultural production and a hotspot for institutional farmland investors. However, investing in farmland—especially in California—comes with many pitfalls, the CEO of a farming company has warned, citing rising bankruptcies in recent years.

He also called for sustainable investor behavior so the state can maintain its productivity and deliver long-term profits for investors.

Farming Powerhouse

The Golden State produces about half of all the vegetables grown in the United States, and more than three-quarters of the nation’s fruits and nuts come from its sun-drenched soil, according to a

report from the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

The state’s farms and ranches generated $61.2 billion in cash receipts in 2024, the first time in history that the state’s agricultural sector passed the $60 billion threshold, the report says.

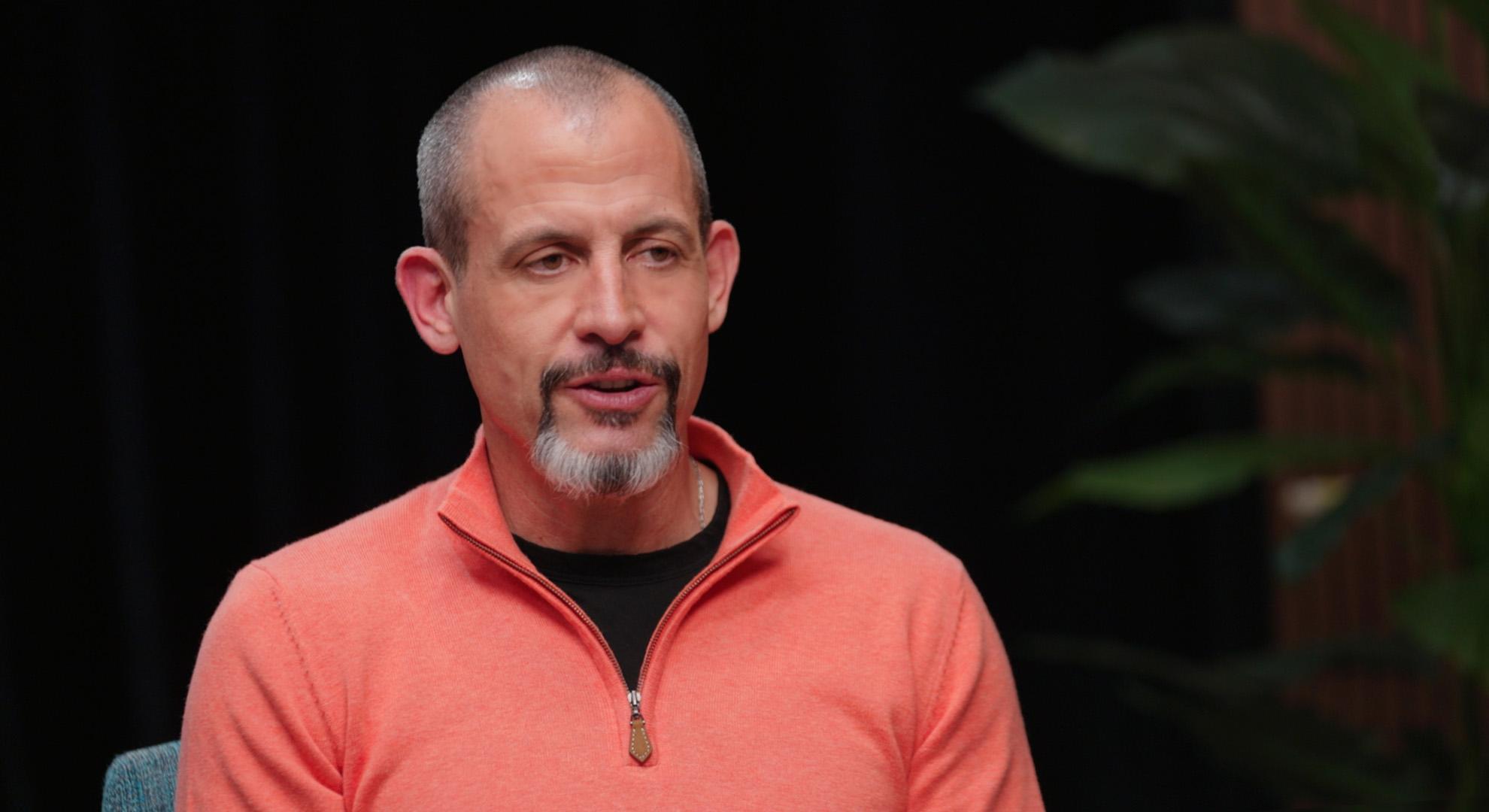

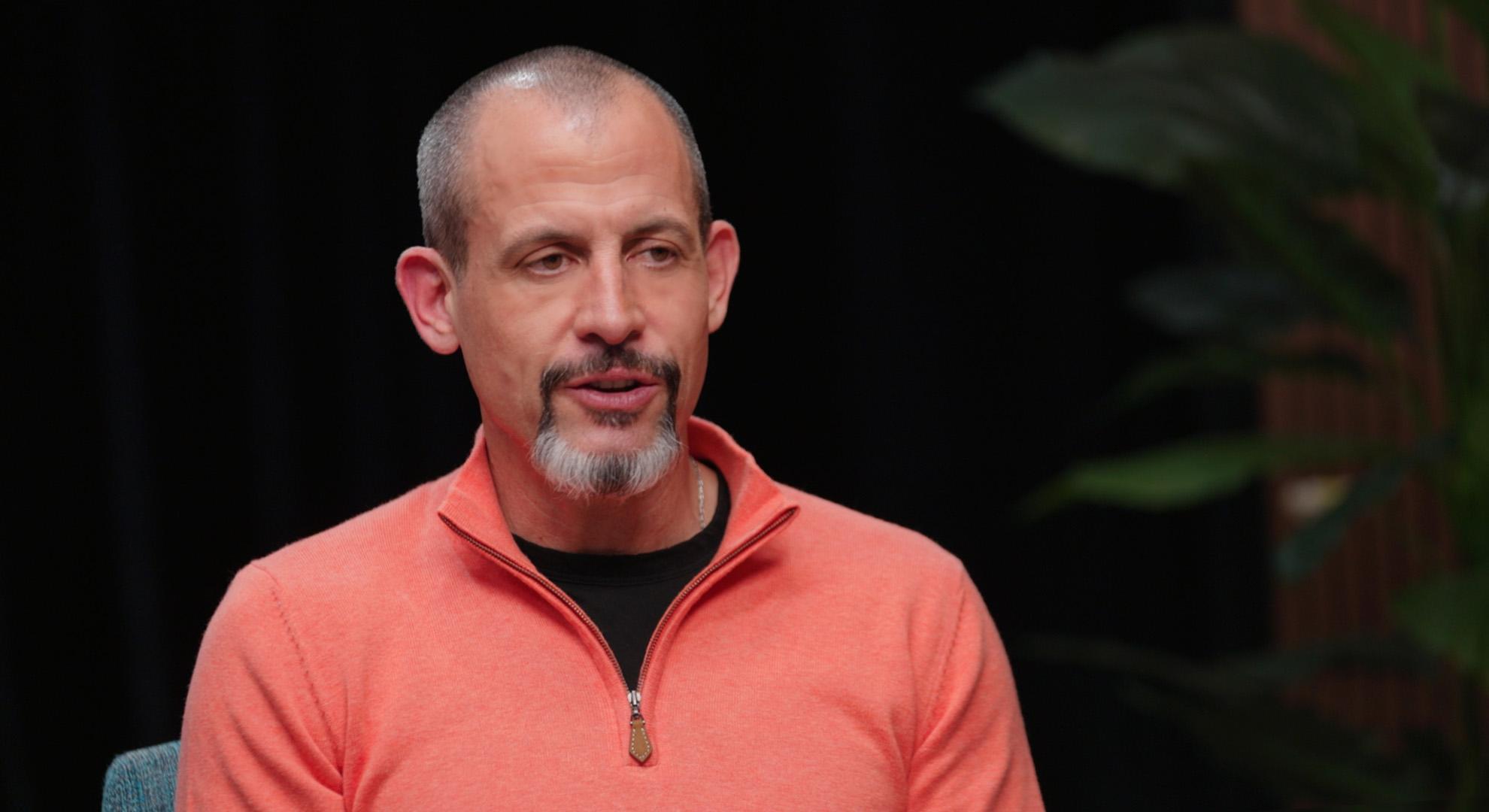

“We grow over 300 different crops, and they’re mostly like the high-value kind of fruits and vegetables, and nut crops,” Cannon Michael, a sixth-generation farmer and agricultural leader, recently told Siyamak Khorrami, host of The Epoch Times’ “California Insider.”

Michael is the president and CEO of Bowles Farming Company, a large family-owned farming business based in Los Banos, California. The company operates 10,000 acres of farmland in the fertile San Joaquin Valley, growing a wide variety of crops, including cotton and tomatoes.

The rich proceeds have drawn scores of institutional investors seeking to capitalize on California’s massive agricultural output.

“In California, agriculture has had a very good track record of proven returns, and so that has attracted institutional investors,” Michael said.

“And institutional investors have been buying land, not just in California, but all over the Pacific Northwest, and even into the Midwest.”

Michael said institutional farmland buyers have mostly invested in almonds, which are a specialty crop that does not do well in other climates or growing regions.

California’s almond growers generated $5.66 billion in cash receipts in 2024, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The state accounts for about 80 percent of global almond production. Export shipments through November 2025 totaled 631 million pounds, and domestic shipments reached 193.5 million pounds. Uncommitted inventory, meanwhile, stood at 1.26 billion pounds.

California is able to maintain its dominant position in the global almond market because it consistently produces higher-quality nuts, Michael said, and that has led to a land rush for institutional capital.

Land planted in almonds accounted for more than $6.5 billion in transactions between 2018 and 2023. However, a spike in interest rates and depressed almond prices has caused many institutional investors to underperform and exit their California land holdings.

“They model out returns that crop prices go up incrementally every year, pegged to inflation or some other metric, which is not how things really work in agriculture,” Michael said.

Cannon Michael, president and CEO of Bowles Farming Company, a large family-owned farming business based in Los Banos, Calif. (The Epoch Times)

Bankruptcies on the Rise

However, there has been a surge in Chapter 12 bankruptcy

filings in California in recent years.

The state led the nation in farm bankruptcies in 2024 with 17, the American Farm Bureau Federation reported, a trend that extended into the first half of 2025 because of a combination of high interest rates, depressed crop prices, rising production expenses, lack of available water in drought years, and poor execution, such as overeliance on a single crop, Michael said.

“A lot of factors go into the success of a farm in a given year, but pricing is one of those things that if it drops, it makes all your other risks that much greater,” Michael said.

“As we have this flagging of prices across all commodities, it’s very challenging for the farming community.”

Availability of dedicated water resources greatly affects California’s cropland prices and crop performance, Michael said.

In the San Joaquin Valley, an eight-county region extending south from Sacramento to the Tehachapi Mountains of Southern California, water primarily comes from surface and groundwater storage. Water rights and availability have become a key aspect of every land transaction.

“There are a lot of large investors in California, and they’ve had to learn a lot about water availability and supply,” Michael said.

“A lot of people were buying land where they didn’t have a solid supply, and some have lost those investments because of water supply issues. In California, where your water supply comes from is the first question, and then all the other questions follow.”

Farming risk compounds exponentially for institutional investors who depend on a single crop, Michael said. Institutional buyers who only planted almonds found themselves in difficult economic positions when prices fell and water became scarce.

“A lot of institutional buyers bought land just for almonds,” he said.

“Sometimes people bought very overpriced land, and they didn’t have water security. So now [they] have very large carrying costs, but they also don’t have the water to make sure they can produce all the almonds they need to be economically viable. Those are the hard lessons people are learning.”

Almonds, ready for harvest, hang on an almond tree branch. (Cristina Quicler/AFP via Getty Images)

Advice for Investors

Farming is a long-term investment, Michael said, which often clashes with the institutional investment mindset of holding an asset for eight to 10 years before liquidating the position.

In pursuit of quick profits, he said, some institutional investors pumped groundwater so aggressively that the ground sank in some areas.

“The ground is actually compressed and fallen away because they pumped all the water from under the ground,” he said. “When you see things like that ... it’s concerning.”

Michael suggested that part of the reason some regulations were implemented on farmland investment is that “there was some behavior that was happening that wasn’t very sustainable, and I think it was mainly driven by profit motivation, not by kind of that long-term thinking.”

He said he hopes future investors will learn from their predecessors’ mistakes and be more careful in their actions.

“I hope that most of the farmland continues to be owned by family farms. I think that’s better for California in the long run,” Michael said.

He said that many investors do work with local family farmers because “they’re not equipped to manage the farmland; they need a partner.”

“We manage farmland for outside investors, and that’s been a benefit, because we let them understand the challenges, and you can make good partnerships,” he said.

“It depends on the style of the investor. Some investors care a lot more for their assets and understand agriculture, and some just want to look at something as a return part of their portfolio.”

Michael also offered advice on investing in California farmland. He said investors should first identify farming areas that are well-suited to the crop types they are interested in. They should then choose a partner who understands farming and can guide them through the process.

He emphasized that investors do their due diligence and “spend time on the ground.”

“You know, it’s much different than buying shares of stock or something. ... It’s an asset with a lot of nuances,” he said.

He also reminded investors to take a long-term view of farmland investing and to consider historical trends in crop prices, “not just expecting that crop prices always go up.”