The first trade deal to emerge from the Trump administration’s global tariff blitz is a narrow pact with one of the United States’ closest allies and a potential bright spot for U.S. agriculture.

The White House said the Economic Prosperity Deal with the UK, signed June 16, includes “billions of dollars of increased market access for American exports, especially for beef, ethanol, and certain other American agricultural exports.”

The deal will provide tariff relief on British car exports, although deals on steel and aluminum have not yet been finalized.

The agreement will reduce or eliminate UK tariffs and nontariff barriers—which, according to U.S. President Donald Trump, have unfairly discriminated against U.S. goods—on some agricultural products, giving U.S. producers a $5 billion boost.

During a May 9 Oval Office news conference to announce the deal, a reporter asked Trump if he was calling on the UK to accept all U.S. beef and chicken, referencing a long-simmering standoff over food standards between the two countries regarding hormone-treated beef and chlorine-washed chicken from the United States, both banned in Europe and the UK.

Trump suggested that the UK could “take” what it wants from the United States’ agricultural options.

He also mentioned that Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is seeking to shift U.S. food standards—likely toward those of the UK and Europe, “with no chemical, no this, no that.”

And on May 22, Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again commission delivered a report taking aim at processed food and chemical toxins as drivers of chronic disease and declining health among U.S. children.

There are questions about how far the principles underlying the report will be extrapolated across the administration. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has signaled that it does not plan to implement a “European mandate system that stifles growth” to reduce pesticide use.

But it was an encouraging step for those hoping that this administration will take a more precautionary approach to regulating food safety.

During Trump’s comments at the May 9 news conference, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins interjected to add, “American beef is the safest, the best quality, and the crown jewel of American agriculture for the world.”

The exchange highlighted a significant difference between the two countries. The United States continues to use agricultural and animal management substances that are banned in the UK, including certain pesticides, genetically modified crops, growth hormones, and antibiotics.

Since the years leading up to Brexit—the UK’s 2020 departure from the European Union (EU)—when the country appeared ripe for prying from Europe’s regulatory apparatus, the U.S. government and agriculture industry have been aggressively lobbying to remove trade barriers for agricultural products.

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and U.S. President Donald Trump shake hands after a joint press conference at the White House in Washington on Feb. 27, 2025. In May, the Trump administration reached a trade deal with the UK, granting limited U.S. market access in exchange for tariff relief on British car, steel, and aluminum exports. (Madalina Vasiliu/The Epoch Times)

This may prove more difficult now, as the UK on May 19 reached a deal to “realign” with the EU on several key issues, among them food safety and animal welfare standards.

Meanwhile, UK leaders have vowed that the new trade framework with the United States will not affect standards—affirming that a ban on hormone-treated beef and chlorinated chicken is a “red line” in negotiations.

Details are scant so far on the final terms of the deal and how it will ultimately shake out for the industry on both sides of the Atlantic.

And while some UK industry groups worry that an influx of U.S. products will drive down standards and prices, some U.S. observers see an opportunity to produce higher-quality U.S. exports.

A 1st Step

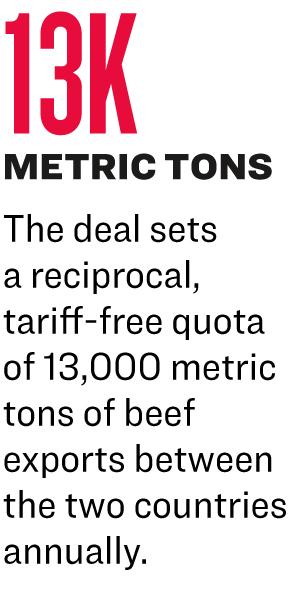

Trump has touted the deal, which establishes a reciprocal tariff-free quota of 13,000 metric tons of beef exports between the two countries each year—as a breakthrough that will increase access for “virtually all of the products produced by our great farmers.”

The White House has estimated that the deal will create a $5 billion opportunity for U.S producers, with more than $700 million in ethanol exports and $250 million “in other agricultural products, such as beef.”

U.S. agricultural producers involved in years-long lobbying efforts are hoping that a lot more will follow.

“For too long, the UK has limited America’s food and agricultural exports to the world’s sixth largest economy and now President Trump’s deal promises to level the playing field,” the International Dairy Foods Association said in a statement.

The U.S. Meat Export Federation thanked the Trump administration in a statement for prioritizing red meat in negotiations, and pushed for the inclusion of pork and the removal of remaining nontariff barriers.

As U.S. beef has not had any duty-free access to the UK since 2020, when the UK left the EU, the quota of 13,000 metric tons is important, Joe Schuele, senior vice president of communications for the federation, told The Epoch Times in an email.

But for U.S. producers to capitalize on the quota, barriers in existing export programs will have to be addressed, Schuele said, noting that the UK still adheres to all import requirements imposed by the EU for beef and pork.

Vehicles carrying chilled meats and other items from the UK mainland disembark at Larne port in Larne, Northern Ireland, on Dec. 31, 2021. The recent U.S.–UK trade deal highlighted long-standing differences in food standards, including U.S. hormone-treated beef and chlorine-washed chicken, both banned in the UK and Europe. (Charles McQuillan/Getty Images)

“There are so many layers of bureaucracy that go above and beyond these two programs [beef and pork] that it’s hard for livestock producers to view them as viable paths into the European market,” he said.

While discussion of the UK’s nontariff barriers often focuses on the use of growth hormones—banned in the UK in 1989—Schuele pointed to other costly requirements hindering U.S. exporters, including “cumbersome plant approval procedures” as well as residue testing and antimicrobial wash restrictions imposed only by the UK and EU.

Protection not Bureaucracy

Where U.S. producers might see cumbersome bureaucracy, UK producers tend to see protection for food quality and prices.

Tom Haynes, head of the UK’s National Pig Association, said allowing U.S. pork imports would undercut UK prices and undo decades of work to improve standards.

“Allowing goods into the UK produced to standards that would not be legal for our producers, would represent a betrayal to British farmers,” Haynes said in a statement on May 9.

He noted that the United States tried hard to get pork into the first part of the deal, with “intense lobbying from the U.S. pig sector, and an 11th hour call from the U.S. President to the Prime Minister.”

Rollins said on May 13 that pork and poultry “are at the front of the line” in continued negotiations, along with seafood and rice.

UK poultry farmers were also happy to be left out.

“Excluding chicken from a UK–U.S. trade deal demonstrates a commitment to responsibility and transparency that defines British poultry meat production,” said Richard Griffiths, head of the British Poultry Council.

In a post on social media platform X, Liz Webster, founder of the nonprofit Save British Farming, said the deal would set a precedent, opening up a “flood of import [sic] food from countries that subsidise their farmers and allow lower standards.”

Farmers drive tractors past the Palace of Westminster during a Save British Farming protest in London on March 25, 2024. The demonstration opposed UK food policy, substandard imports, and stricter labeling rules, with farmers calling for action to protect British agriculture. (Henry Nicholls/AFP via Getty Images)

Risk Analysis

In its statement celebrating the deal, the White House pointed to UK tariffs, some higher than 125 percent, on U.S. meat, poultry, and dairy products. Added to the tariff burden, it said, are “non-science-based standards that adversely affect U.S. exports.”

The week after the deal was announced, Rollins met with UK officials and industry leaders to promote consumer choice and regulation based on science-based risk analysis, while stressing the safety of U.S. food and looking to dispel “misinformation” she said has circulated for decades in the UK.

Responding to questions about hormone-treated cattle at a news conference in London on May 13, Rollins said, “We have decades of research that show the beef produced in America, whether it’s hormone or hormone-free, is entirely safe.”

The secretary also clarified that over the past decade, the U.S. poultry industry has shifted away from using chlorine to wash poultry.

“Chlorine chicken—that’s a narrative in your country we have not done a good enough job pushing back on,“ she said. ”Only about 5 percent ... of our chicken in America is actually treated that way.”

To disinfect chicken, U.S. chicken producers now mostly use peracetic acid, an organic compound—basically an industrial-strength equivalent of hydrogen peroxide and vinegar—that the European Food Safety Authority in 2014 deemed safe for use on meat.

UK regulators do not have an issue with the chlorine wash itself; both the UK and the EU permit chlorine washing. The UK approach is based on the position that proper hygiene and animal welfare make chlorine washing unnecessary—it is seen as a cover-up for low standards associated with large-scale factory farming.

While the UK’s “farm to fork” model includes tracing food hygiene at all stages of the production process, the United States has historically relied on end-stage testing to ensure safety.

A new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rule will require traceability for a limited list of foods, including cheeses, eggs, and some produce and seafood items. However, that rule, mandated in 2010 and finalized in 2022, has yet to be enforced. The compliance date for the final rule has now been pushed back to July 2028.

Since the 2016 Brexit referendum opened a potential route for direct trade with the UK, U.S. officials and industry stakeholders have criticized what they consider Europe’s unfounded fears over food quality and safety, framing the U.S. approach as more modern and “science-based.”

In a 2019 op-ed, former U.S. Ambassador to the UK Robert Wood Johnson likened Europe to a “Museum of Agriculture,” contrasting its focus on history and tradition with the United States’ focus on science and innovation—a philosophical distinction, not a difference in quality, he said.

The same year, U.S. agricultural producers testifying during a public hearing to inform trade negotiations suggested that European restrictions on drugs such as ractopamine—a feed additive widely used in U.S. pork—lacked scientific basis and should be dropped.

Dave Ayares, president and chief scentific officer of Revivicor, pets genetically altered piglets at the Revivicor research farm in Blacksburg, Va., on Nov. 20, 2024. Pork has been a key issue in U.S.–UK trade talks, with the head of the UK pig association warning that U.S. imports could undercut prices and reverse decades of progress on standards. (Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images)

Research on human health effects of the drug is nearly nonexistent, but a lack of evidence proving its safety and concerning links to animal health issues have led more than 160 countries—including Russia and China, the biggest consumer of U.S. pork—to ban it.

The example demonstrates the difference in approach between the United States on the one hand and the EU and UK on the other. Absent scientific consensus about the health impacts of a drug or additive, European governments have typically prioritized human health and safety as a precaution when there are signs that a substance may pose a threat.

This “hazard-based” approach is based on the “precautionary principle” enshrined in European law.

Or, as the UK Food Standards Agency defines it, “In the interests of protecting public health from emerging food safety risks, the precautionary principle allows us to take action even if there isn’t time or data to undertake a full risk assessment.”

The United States, on the other hand, favors a “risk-based” approach focused on managing the risks of a potentially hazardous substance, often one that is already widely used.

“I think as soon as the UK can free itself from the precautionary principle, we’ll have a lot more opportunity to trade based on sensible regulations that are aimed at public health and safety, not at ill-founded fears,” Daniel Griswold, trade policy expert at George Mason University, said during a 2019 public hearing.

Pesticide Use

Pesticide use is another area in which the UK’s precautionary approach distinguishes it from the United States, but increasingly less so.

The UK plans to phase out chemical pesticides and reduce agricultural use of antimicrobials in the next several years. The United States has no such plan, but has offered some incentives in recent years to help farmers transition to organic.

The United States also allows higher maximum residue limits for pesticides than the UK for many foods—sometimes hundreds of times higher—and approves more pesticides than the UK and EU, according to an analysis by Pesticide Action Network.

In the UK, companies must prove no harmful effects on human health or the environment before active substances—the active components of pesticides—can be approved for use, and regulators can restrict use of a substance based on correlation with harmful effects, without requiring proof of causation.

Customers eat lunch overlooking the Palace Pier, outside Captain's Fish and Chips shop in Brighton, England, on March 25, 2022. (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

Before a company can sell a pesticide in the United States, the EPA reviews studies “to ensure that it will not pose unreasonable risks to human health or the environment, while considering the economic, social and environmental costs and benefits,” according to the federal government.

And while the United States allows “conditional registration” of pesticides before a full risk assessment is done, the UK reviews approvals every 15 years, or sooner if evidence or concerns arise.

Since leaving the EU, the UK has come under fire from environmental groups for extending the period of time before approved pesticides are subject to a new risk assessment, and for granting emergency use authorization for pesticides banned by the EU, in particular neonicotinoids known to be harmful to bees and other pollinators.

In response, in 2024 the government said it would phase out emergency use of this class of pesticides and has since at least partly followed through.

The United States uses an estimated 1 billion pounds of pesticides each year, and on average, from 2008 to 2012, has accounted for nearly one-quarter of the total applied worldwide.

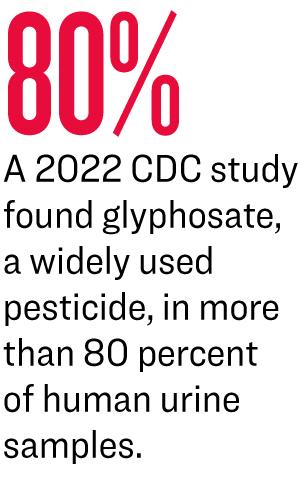

A 2022 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study found glyphosate, the most widely used pesticide in U.S. agriculture, in more than 80 percent of human urine samples. But according to the annual pesticide data summary from the Department of Agriculture (USDA), more than 99 percent of tested produce samples had residues below tolerances established by the EPA, and 38.8 percent had no detectable residue.

In 2021 the UK reported that almost 50 percent of 3,530 agricultural samples contained no pesticide residues, with about 40 percent containing residues below the maximum residue level and only 2.55 percent containing levels above it.

Despite mounting evidence that exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides can cause immunological, reproductive, metabolic, carcinogenic, and other harm, there remains a lack of global scientific consensus.

A farmer spreads pesticide on a field in Centreville, Md., on April 25, 2022. Pesticide use differs between the UK and United States, but increasingly less so. (Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images)

Since the World Health Organization classified the herbicide as “probably carcinogenic” in 2015, there have been hundreds of scientific papers on it, with recent research pointing to links with a range of diseases, including cancer, endocrine disruption, depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and infertility.

California has listed the herbicide as a cancer-causing chemical since 2017, and manufacturers have paid more than $11 billion in legal fees to settle more than 100,000 related lawsuits.

U.S. federal regulatory agencies said existing studies are insufficient to prove carcinogenicity, and the EPA in 2020 determined that there are no risks of concern to human health.

The UK has authorized use of glyphosate through December 2025.

And while the UK’s maximum residue levels apply to food no matter where it is produced, activists have noted that these have increased since Brexit, and are further threatened by free trade agreements.

Nick Mole, policy officer with Pesticide Action Network, told The Epoch Times that he is concerned that trade deals will put pressure on the UK to further increase allowable levels, allowing “higher levels of potentially harmful pesticide in food introduced from the U.S.”

Antibiotics and Hormones

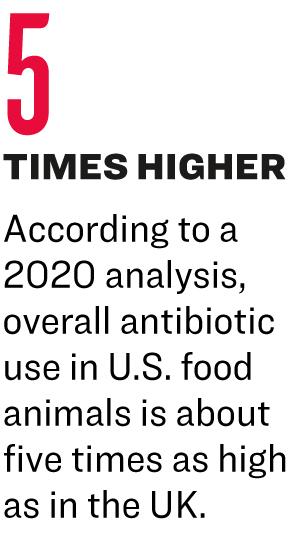

U.S. producers also rely far more on antibiotic use than do their UK counterparts. According to a 2020 analysis from Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, a UK-based group that campaigns to curb the use of antibiotics in farming, overall antibiotic use in U.S. food animals is about five times as high as that in UK animals; in cattle, it is nine to 16 times higher.

The drugs can kill some bacteria but leave others intact, potentially causing deadly bacterial outbreaks.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing worldwide health concern, directly responsible for about 1.2 million deaths in 2019, and contributing to 4.95 million deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

In 2017, the United States phased out licensing antibiotics to promote growth in animals; technically, they are supposed to be used only for disease control. Despite that, according to National Institutes of Health data, about 70 percent of medically important antibiotics sold in the United States are used in farm animals.

In the United States, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System shows that fluoroquinolone-resistant and other drug-resistant E. coli have steadily increased in swine samples, and multidrug-resistant Salmonella has increased among chickens.

Chickens stand in a henhouse at Sunrise Farms in Petaluma, Calif., on Feb. 18, 2025. From July 2028, a new FDA rule will require traceability for certain foods—including cheeses, eggs, some produce, and seafood. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

In 2024, the UK implemented new restrictions banning routine antibiotic use in farm animals and the use of antibiotics “to compensate for poor hygiene, inadequate animal husbandry, or poor farm management practices.”

Regarding the United States’ hormone-enhanced cattle, banned in the UK and Europe since 1989, the FDA maintains that added hormones—widely used by U.S. farmers to speed up growth rate and more efficiently convert feed into meat—do not pose any risk to human health.

But there are now decades of research linking those compounds with cancer and developmental and reproductive harm. Hormone exposure is a known risk for developing certain cancers—70 percent to 80 percent of breast cancer in the United States is hormone receptor-positive—while endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as pesticides, have been shown to cause cancer and other diseases in humans.

More recent research has called into question current health-based intake limits set by the United States for hormone-treated beef, which are typically based on studies in adult animals and do not account for impacts during sensitive developmental periods.

GMOs

On genetically modified organisms (GMOs), the UK has moved closer to the United States’ more liberalized approach.

In the United States, more than 90 percent of corn, cotton, and soybeans are produced using genetically engineered varieties, with herbicide-tolerant and insect-resistant being the most commonly used categories, according to the USDA.

Meanwhile, more than 95 percent of animals used for meat and dairy in the United States eat genetically modified crops, according to the FDA.

The government recently began requiring bioengineered foods to be labeled if they contain a “detectable” component.

For years, studies have shown that a clear majority of Americans are concerned about genetically modified foods and have long thought that they should be labeled—even before there was any requirement to do so. A 2019 Pew Research study showed that slightly more than half of U.S. adults thought that genetically modified foods were less healthy than foods with no genetically modified ingredients.

Most European countries, along with Russia, India, and others, have banned the cultivation or importation of genetically modified foods.

In the UK, foods must be labeled to indicate whether they contain GMOs or contain ingredients produced from GMOs, but foods produced with the help of genetic modification technology do not need to be labeled. Meat, milk, and eggs from animals that are fed on GMO feed do not require labeling.

In 2023, the UK loosened restrictions on the commercialization of “precision bred” organisms, eliciting significant backlash. Precision bred organisms are genetically modified, but in such a way that the changes are equivalent to those that could have been made using traditional breeding methods.

A calf is fed at a farm in Otisville, N.Y., on Jan. 29, 2023. (Samira Bouaou/The Epoch Times)

Animal Welfare

On animal welfare, there are significant differences between the U.S. system and the UK system, which has adopted even stricter regulations since leaving the EU.

In an April report, UK animal welfare groups highlighted vulnerabilities where trade policy can exacerbate existing loopholes.

The UK banned battery cages for laying hens in 2012, according to the report, but they are widely used in the United States, while sow stalls, used to confine pregnant pigs, have been banned in the UK since 1999 but remain legal in 39 U.S. states.

“While much previous and current public discussion around a potential US–UK trade deal has centered on food safety issues ... the animal welfare implications are equally concerning,” the report stated, pointing to the absence of federal legislation in the United States protecting farmed animals during rearing.

Meanwhile, while most cattle in the UK are at least partly pasture-raised, grass-fed beef in the United States accounts for only about 5 percent of total production.

What Does This Mean for Farmers?

Whereas the United States has evolved to mass-produce agricultural export commodities, Europe’s focus remains a patchwork of regional specialties and higher-value exports. While the UK has adopted some U.S.-style practices since Brexit, it remains largely aligned with the EU. UK farmers, and the public and politicians that support them, want to protect standards that have taken decades to develop and keep their product value high.

In his 2019 op-ed in the UK’s Telegraph, Wood Johnson wrote: “The fact is that farmers in America have the same priorities as farmers in Britain. They pass on their farms from one generation to the next. They care deeply about their land and livestock and they take tremendous pride in the food they produce.”

But free trade agreements tend to favor conventional agricultural producers—who have a competitive advantage of scale, infrastructure, and resources—not necessarily smaller, family-run farms.

Squeezed by multiple pressures, smaller and mid-sized farms in the United States are disappearing. According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, the United States lost almost 142,000 farms between 2017 and 2022, with farm acreage falling by more than 20 percent in the same period.

(L–R) White House domestic policy director Vince Haley, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, President Donald Trump, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Education Secretary Linda McMahon, and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin attend an event at the White House on May 22, 2025. A new Make America Healthy Again Commission report targets processed food and chemical toxins as key contributors to chronic disease and declining health among U.S. children. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

In an era defined by conglomeration, particularly at the packing stage, smaller producers often cannot compete or do not have access to export markets.

According to a 2023 USDA report, the beef and pork sectors have had “significant plant consolidation” over the past 30 years, while chicken has “held a more uniform distribution over time.”

As the largest beef and pork plants have gotten larger, the share of animals at smaller processing facilities has remained flat. Across all species, the report found, the largest four firms control approximately 51 percent of the total value of U.S. livestock production.

The USDA estimates that the four largest beef processors accounted for 81 percent of the total market in 2021.

The U.S. poultry market is also one of the most consolidated sectors in the U.S. food system. According to a report from nonprofit Farm Aid, independent farms made up 95 percent of those producing chicken meat in 1950; five years later, they accounted for 10 percent, with most growers selling under contract with a larger company. The top four poultry firms controlled 60 percent of the market in 2022.

This highly consolidated production model relies on the confinement of animals packed into tighter spaces, where the prevalence of disease pressure is higher and more antibiotics are required.

Decades of market concentration have also led to a U.S. agricultural trade strategy centered on mass-producing and exporting commodity crops such as soy and corn.

According to a recent article by the nonprofit Farm Action, this focus on commodities comes at the expense of domestic production of higher-value food crops and has contributed to the country’s growing agricultural trade deficit.

As U.S.-style “mega farms” in the UK increased in the years leading up to Brexit, the issue became a heated domestic issue.

Ranch hands drive cattle to a new pasture against the backdrop of hills covered in blue, yellow, and orange wildflowers at Carrizo Plain National Monument near Taft, Calif., on April 6, 2017. (Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images)

“One thing is clear: I do not want to see, and we will not have, U.S.-style farming in this country,” Michael Gove, the UK’s then-secretary of state for environment, food, and rural affairs, told Parliament in 2017. “The future for British farming is in quality and provenance, maintaining high environmental and animal welfare standards.”

An analysis of U.S. Agriculture Census data by the U.S.-based think tank Sentience Institute shows that nearly all animals raised for meat in the United States are “factory farmed,” but the UK is not far behind. According to the nonprofit Compassion in World Farming, 85 percent of animals are now factory farmed in the UK.

In an emailed statement, Compassion in World Farming said the U.S.–UK agreement “exposes the low standards and corporate-driven priorities that continue to shape U.S. food and farming policy.”

“U.S. consumers deserve the same high standards,“ said Matthew Dominguez, the organization’s U.S. director. ”Anything too cruel or risky for British families shouldn’t be on our shelves.”

Jaydee Hanson, policy director for the Center for Food Safety, noted concern over the idea that the United States might pressure other countries to lower their standards, but told The Epoch Times via email that thus far this has not happened. U.S. organic standards already meet European export requirements, Hanson said.

Schuele, of the U.S. Meat Export Federation, said U.S. producers, including smaller exporters and traders, would be more interested in Europe if they had more freedom to process animals at any USDA plant, and not just those approved for the EU and UK.

And some see the U.S.–UK agreement as an opportunity for smaller operations, with the potential to pave the way for a new model.

“It is great to see that President Trump’s trade deal with the United Kingdom prioritizes new market opportunities for American farmers and ranchers,” Joe Maxwell, co-founder of Farm Action, said in an email to The Epoch Times.

“[The deal] would expand market access and economic returns for U.S. beef producers willing to differentiate their production practices to meet the U.K.’s higher standards.”