(Illustration by The Epoch Times, Samira Bouaou/The Epoch Times, U.S. Department of Justice, Public Domain)

After the bloodshed of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, U.S.–China relations hit a low point. Official Chinese media outlets suffered such a backlash in the United States that Beijing was burning to find alternative avenues to broadcast its narrative.

Then, in New York, China Press was born, a Chinese-language newspaper founded by Xie Yining, now deceased, who made it the outlet’s mission to promote friendlier U.S.–China ties.

Xie had worked as a White House correspondent for China News Service, the second-largest Chinese state-owned news agency, which the United States in 2020

designated as a foreign mission.

China Press, which maintains an office in Beijing, rose as a valued asset for Beijing with its mainland China-focused coverage, at a time when “China’s voices had virtually no other outlet to spread overseas,” You Jiang, CEO of China Press,

wrote in a 2014 essay outlining the outlet’s expansion plans.

During the outlet’s fledgling days, top communist leaders “frequently met” with its executives, granted the newspaper rare interviews, and gifted handwritten plaques as tokens of appreciation, gestures that “undoubtedly aided China Press in establishing itself as an authority on China news coverage,” Mr. You recounted. He described overseas Chinese media such as his as “a key supplementary part” of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) overseas propaganda.

With such privileges, China Press thrived. By its own account, the regime’s “ever-growing global influence” and the “brisk expansion of mainland Chinese immigrants” made China Press the “fastest-developing Chinese language newspaper in America.”

The Chinese name for China Press, Qiaobao, translates to “Chinese diaspora newspaper.” CCP officials have

described such overseas Chinese language media as one of “three treasures” used to further its control over the Chinese diaspora.

The word Qiao, or diaspora, is also a homophone for bridge, which the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, the ministry-level department that directs Beijing’s covert global influence operation, invoked in the early 1990s as it looked for ways to reshape global discourse, according to a former press officer for the body.

“These ‘Qiao’ publications carry power that the ‘official army’ cannot wield,” the press officer recalled CCP officials saying. By using the publications as a bridge, the officer told The Epoch Times, the officials saw that they could “go global.”

China Press rose to the occasion.

The China Press building in Alhambra, Calif., on Nov. 16, 2018. Xie Yining, founder and chairman of China Press, was shot to death inside the publication’s office on Nov. 16, 2018. (Linda Jiang/The Epoch Times)

China Press now

flaunts itself as the only Chinese media outlet in the United States that uses simplified characters and has a Beijing-based news center to cater to immigrants from mainland China.

Its bright red logo, a color favored by the CCP, has made its way into Chinese grocery stores and newspaper stands in some of the biggest U.S. cities, including New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and the Washington area.

It has gained constant favor from CCP officials. Writing in dedication to China Press on its 25th anniversary in 2015, then-New York Chinese Consul General Zhang Qiyue

called it “a Chinese-language U.S. newspaper building a bridge between the United States and China.”

China Press’s media executives are

regulars at high-profile media forums held in China and have nabbed several exclusive interviews with the communist regime’s highest leaders over the years, including former regime leader Jiang Zemin, now deceased; former vice premier Qian Qichen; a Chinese ambassador to the United States; and Yang Jiechi, when he was foreign minister in 2007.

A handwritten plaque from Jiang hung on the wall of Mr. You’s New York City office, according to a former editor there who requested anonymity.

With the United States growing wary of Chinese influence peddling, the role of overseas media as a propaganda arm has also gained scrutiny.

“Communist China’s reach knows no bounds. News outlets must be on guard against Beijing’s deceptive tactics, which seek to undermine our interests and values and manipulate the flow of information,” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) told The Epoch Times. “We must remain vigilant and resolute in defending our freedoms against these threats.”

Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), the outgoing chairman of the House Select Committee on the CCP, told The Epoch Times last year that “there should be a warning sign” making clear the entity is “an appendage of the CCP and its propaganda.”

In December 2023, in a short

clip titled “United Front 101,” he called out China Press by its Chinese name, Qiaobao.

“Several overseas Chinese media outlets are owned or controlled by the [United Front] Work Department through Chinese news services, including Qiaobao, which operates in the U.S.,” he said.

A Firm Reporting Policy

In July 1997, China Press

boasted of being the only overseas Chinese-language newspaper allowed to attend the ceremony for Hong Kong’s handover to Chinese control.

Its special coverage began 30 days ahead of the event. Ten editorials appeared during that period, offering full-throated support for the handover.

A man holds a poster of the famous “Tank Man” standing in front of Chinese military tanks at Tiananmen Square in Beijing on June 5, 1989, during a commemoration of the 1989 Tiananmen Square event, in Victoria Park in Hong Kong on June 4, 2020. (Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images)

In dispatches from Hong Kong, its reporter

gushed over how Tung Chee-hwa, Hong Kong’s first new leader-to-be and an 18-year vice chairman of China’s top political advisory body, “charmingly” brushed off a question about the Tiananmen Square massacre by focusing on the celebratory mood.

On the eve of the event, after thousands of Chinese soldiers

marched into Hong Kong, China Press’s reporter

warned Washington to mind its tongue and not to “meddle” in Beijing’s affairs.

Such an admonishment would have been nothing remarkable in any Chinese state-controlled media. China Press, however, is ostensibly a privately held entity established in the United States.

Chinese media

articles and

obituaries penned by China Press reporters show that Xie declared a no-tolerance policy toward anything deemed to interfere with “the reunification of the motherland.”

For any coverage that reflects on the “dark side of Chinese society,” he instructed reporters to “investigate in depth to see if they are real.”

Chinese officials frequently affirm China Press’s work in public. I-Der Jeng, the reporter sent to Hong Kong in 1997 and now China Press’s chief editor,

advises a Chinese state-run magazine favored by top Chinese officials and was a

guest at the official ceremony for the regime’s 70th anniversary in 2019, according to Chinese media reports. His glowing remarks about Beijing are

featured in the pages of China’s major state media from time to time.

Mr. You returned to China in 2020, the former editor said.

He became the deputy director of a Hong Kong magazine and

arranges the city’s writers to visit the mainland for “literary exchanges.”

The China Press office in New York City on April 8, 2024. (Chung I Ho/The Epoch Times)

‘Lifeline’

The Beijing-based Overseas Chinese Affairs Office’s chief responsibility is to direct the CCP’s “United Front work,” which reshapes narratives, advances the regime’s agenda, and suppresses dissident voices.China Press has denied direct affiliation with the office, but its former staff see it differently. A former China Press reporter, who returned to China before the COVID-19 pandemic, had named the office as his workplace on social media. “United Front work” was a main duty he highlighted in his listed work experience at the outlet on his LinkedIn profile.

A look at China Press’s financing also raises questions.

China Press doesn’t appear to generate much profit from distribution. It is distributed for free in New Jersey, Los Angeles, and Boston, and it sells for 50 cents in New York City’s Chinatown. As of 2018, 75,000 copies of China Press were circulated each day in New York City, Boston, and Washington, according to a

statement from the College of Staten Island highlighting the newspaper’s coverage.

“With little advertising and no one buying it, where does it get money?” a former assignment editor at a state media outlet in China told The Epoch Times, requesting anonymity for fear of reprisals.

He surmised that its funding, in no small sum, comes from China News Service, which is overseen by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office. The funds might not come from Chinese authorities or the news service directly, she said, but through other Chinese entities to mask its origin.

Independently, two former China Press staff members said the same thing.

“China Press doesn’t make money. Its lifeline is the CCP,” the paper’s former editor told The Epoch Times.

The second, a former reporter, agreed.

“When the country is the financier, there’s definitely a way,” he told The Epoch Times. “What if they take a piece of paper and exaggerate some transaction numbers? They can also go through official channels or get money from the Chinese Consulate. There’s no way to find out. They can do business with companies based here.”

Even with the alleged money factor aside, the close affinity between China Press and Chinese state entities is hard to ignore.

In annual “overseas Chinese media advanced training courses” hosted in Beijing, senior staffers from China Press, and its broadcast-focused sister outlet SinoVision, present themselves as eager students.

At a graduation ceremony in which a China Press executive spoke, an Overseas Chinese Affairs Office official congratulated the trainees for completing the class and

voiced expectations for them as “builder, disseminator, and defender of the Chinese image abroad,” according to state media reports.

China News Service is one of many Chinese news agencies that

partners with China Press. For years, the Beijing-based outlet has sent staff members to work at China Press’s New York City office, according to the former China Press editor. They usually stayed for months.

Through an

agreement with the Central School of Communist Youth League of China, which trains young communist leaders, postgraduates also work alongside China Press’s New York City staff and publish their work in the newspaper,

records from the school show.

Chinese choir members stand together at a ceremony marking the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party at Tiananmen Square in Beijing on July 1, 2021. (Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

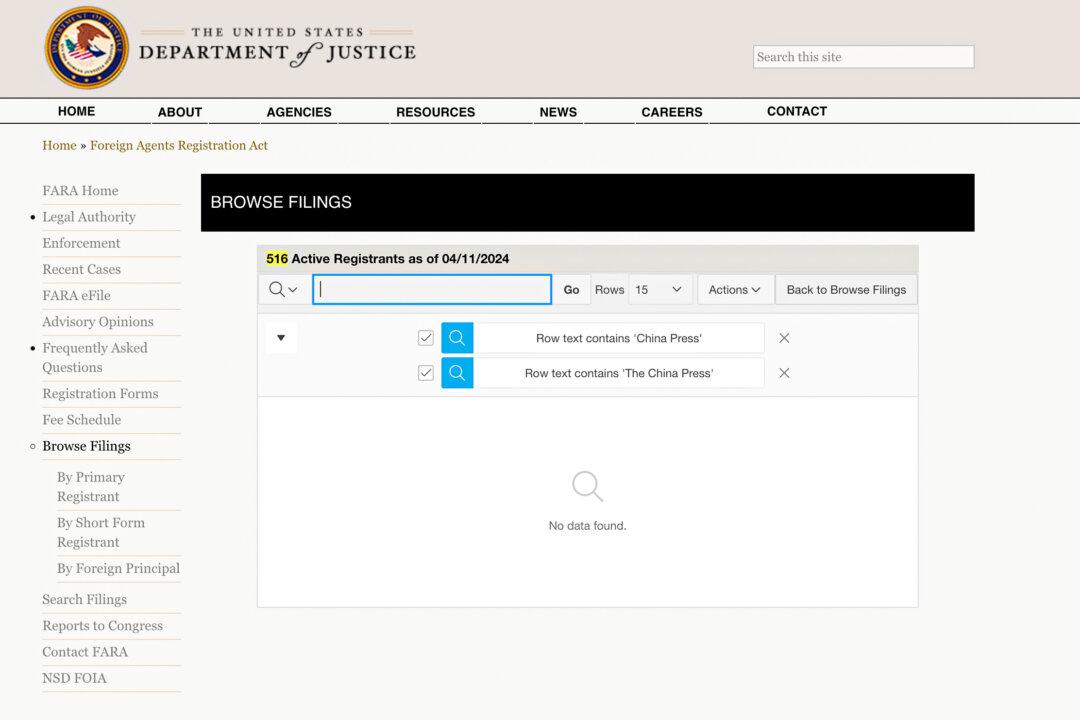

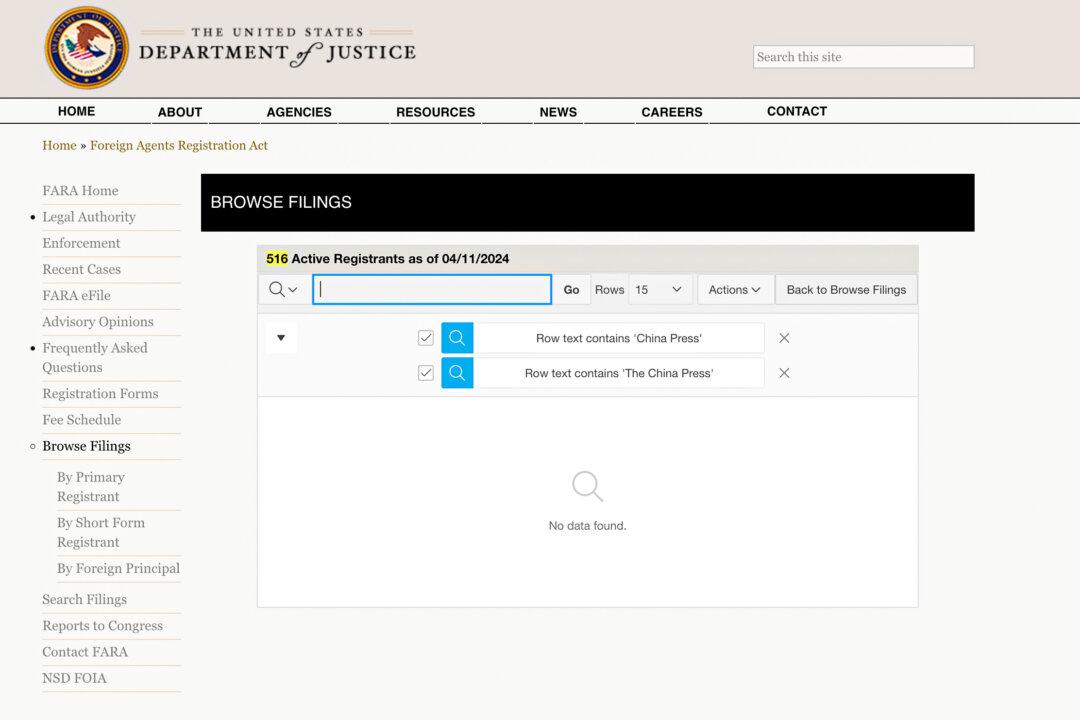

No US Oversight

Unlike official Chinese state-affiliated entities such as China Daily, China Press has been shielded from U.S. oversight because of its private ownership. The newspaper is not registered as a foreign agent with the U.S. Justice Department, which would compel more transparency on its activities.In practice, though, whether the entity is privately held makes little difference, say China analysts and people who have worked with Beijing-linked entities for years.

“If it looks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck,” Sarah Cook, an independent researcher and lead author on the Freedom House think tank’s

2022 report on Beijing’s global media influence, told The Epoch Times.

The former assignment editor in China, already a green card holder living in the United States, said he was approached in recent years by a Chinese person who offered him a job at any overseas Chinese media of his choosing. China Press was one of the options.

The former Overseas Chinese Affairs Office press officer received an order in the 1990s to feed regular content to China Press for its new special section “promoting accomplishments from China’s nation-building efforts.”

Content on these pages, which appears in the same font as the rest of the paper, also comes from other Chinese state news agencies and government entities, such as Xinhua Daily and China News Service. One northeastern city in China

credited this coverage for bringing in “over 20 faxes” from five prospective U.S. investors, according to local state-owned media.

Such sections have expanded over the years. The newspaper’s digital edition contains dedicated coverage of cities and governments all over China. In one, it touts how a village’s “miraculous” poverty eradication program is “going global.”

“China Press is an overseas propaganda tool for the CCP,” the former Overseas Chinese Affairs Office press officer, who also requested anonymity, told The Epoch Times.

Zhang Jing, a former news editor with New York City-based World Journal and Hong Kong’s Ming Pao, also said as much.

“The only difference is in name,” she told The Epoch Times.

In a “free environment like America,” China Press can do a lot to aid the regime, she said.

“China Press is basically an oxygen pipeline” for Beijing, she said.

A screenshot shows that the China Press newspaper is not listed with the Foreign Agents Registration Act. (Screenshot via The Epoch Times, U.S. Department of Justice)

‘Believe It’s True’

The Chinese community in the United States is the largest overseas population outside Asia. In 2022, it was estimated that more than 5.4 million Chinese were living in the United States, according to Census data.Of them, two-thirds spoke their native tongue at home, and one-third had a limited command of English, leading to a reliance on Chinese-language sources for information.

In this immigrant population, China Press sees opportunity.

Xie, who reigned over China Press for nearly three decades until a co-worker

fatally shot him in his Alhambra, California, newspaper office over a dispute, had once

quoted the Chinese regime spokesman Zhao Qizheng: “If you don’t tell the China story, others will. If you don’t tell the real story, fake news will proliferate,” according to a China News Service report.

The question is, who decides what’s real versus fake?

On hot-button Chinese issues, China Press’s reporting hews closely to Beijing’s narratives. Its editorials openly back TikTok when the app faces U.S. pressure to divest from its Chinese ownership, and local Beijing critics such as

Mr. Rubio and Rep. Chris Smith (R-N.J.) are labeled “anti-China.”

The outlet drew

lawsuits, and recognition from Beijing, for its hundreds of reports maligning Falun Gong—a meditation practice that rapidly gained popularity in the 1990s with its teachings of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance—in the first two years of the regime’s persecution of the practice at the turn of the century.

The CCP has used an aggressive disinformation campaign against the spiritual practice to whitewash and justify its sweeping suppression, which involves mass

detention,

forced labor,

torture, and

forced organ harvesting.

All mentions of Falun Gong have now disappeared from China Press’s website. Also gone are trigger events such as the Tiananmen Square massacre.

The opposite stands true for topics it considers important. As former Taiwanese leader Ma Ying-jeou, known for espousing friendlier ties with Beijing, began his unprecedented 11-day trip to China on April 1, 10 glowing stories

popped up on China Press in less than two hours, all to convey one message: Taiwan, the self-ruled democratic island, should unify with the mainland.

A restaurant owner watches live television coverage of a meeting in Beijing between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou, in Singapore on Nov. 7, 2015. (Greg Baker/AFP via Getty Images)

During major events involving China, such as the 2022 Beijing

Olympics and the November 2023 U.S.–China summit in San Francisco, China Press turns into a space where Chinese front groups exhibit fervor.

Full-sized ads run in the newspaper for days, broadcasting what the Party wants heard in large red characters.

“Injecting positive energy to Asia-Pacific and the world,”

read one November 2023 ad that listed names of more than 100 pro-Beijing groups.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Chinese officials return the favor.

In a 2012 speech marking the 20th anniversary of the China Press’s San Francisco edition, then-San Francisco Chinese Consul General Gao Zhansheng

praised the outlet for its “accurate, timely, in-depth reporting of major domestic political and diplomatic affairs in China and crucial international events.”

In his words, it has “opened an important window” for overseas Chinese to “understand the homeland.”

The former China Press reporter said he never read the newspaper, even while working there. “It’s just a job,” he said. At most, he said, he checked to see if his articles were published.

“A lot of people from Fujian read China Press,” he said, referring to the province on the southeastern Chinese coast that accounts for a large portion of the Chinese immigrant population in the United States.

“They will trust its words because our fellow overseas Chinese still love their country. When they read China Press, they will believe it’s true.”

It’s also convenient for the CCP to launder information: Whatever it prints in support of the regime, the mainland media can quote it and cast it as a sentiment from the United States, because it “represents American Chinese,” he said.

Seeding ‘Future Propagators’

To achieve the regime’s directive to “tell the China story well,” the idea is to have more voices—to “tell it together,” Sun Yumei, vice president of the Overseas Chinese Newspaper of Europe, said at a Beijing-based conference in 2022 strategizing how to spread Chinese influence. Her outlet serves a similar function to China Press.She placed particular emphasis on grooming the younger generation of overseas Chinese to become the “future propagator of China stories.”

China Press has been doing exactly that for years.

Ostensibly providing an opportunity for Chinese American teens to gain real-life journalistic skills, China Press started a “junior reporter club” in 2013, selecting a small cohort for an organized China tour each year. By 2019, the nationwide program had drawn nearly 200 U.S.-raised teens with Chinese language skills.

Chinese authorities played the part of a gracious host, granting the young visitors rare access and time with senior officials and encouraging them to build a career in China. Chinese media outlets printed ebullient remarks from the participants.

Mr. Jeng, China Press’s chief editor,

led the earliest programs. He

noted that the American teens were “experiencing a China like few others could,” with privileges that actual reporters may not even get, a 2013 press release from a New York City Chinese school quoted him as saying.

Chinese state media reports suggest that the effort to transform young hearts and minds was working.

The Confucius Institute building on the Troy University campus in Troy, Ala., on March 16, 2018. (Kreeder13 via Wikimedia Commons)

“They are educated in America, but in classrooms, they are daring enough to challenge teachers who hold a bias toward China, to tell classmates about the real China,”

read a 2016 article in People’s Daily, the Party’s official mouthpiece.

The teens

sang patriotic songs,

admired the Chinese ministry spokesperson’s “skillful handling” of challenging questions, and came away

remembering Confucius Institutes—the state-funded program often criticized for amplifying Chinese propaganda in the West—as a “key platform for the world to understand China.”

A two-time participant on the trip later

returned to study at Tsinghua, an elite university in Beijing, state mouthpiece Xinhua reported in 2017. Another club member, a ninth grader, in 2020

wrote in China Press that the regime’s draconian pandemic lockdowns, while damaging in the short term, “quickly contained the virus and protected the ailing and elderly.”

Political Warfare?

The pandemic appeared to have hit China Press hard.

Its circulation shrank. The pickup site of the Boston edition vanished after November 2019. The weekend edition was axed and layoffs followed, the former staffer said. The junior reporter club activities were

suspended after an end-of-year awards ceremony in 2020.

But the editorial line remained—as did the apparent support from the United Front network. This year, from Feb. 28 through March, the network

ran nine full-page ads in the paper celebrating the anniversaries of various New York City front groups.

These organizations often

work closely with the Chinese Consulate and, sometimes, officials in China.

“The ads aren’t meant for the reader, it’s for the Chinese Consulate,” the former China Press reporter said. “Where else would you put up such ads except on China Press?”

During the November 2023

U.S.–China summit in San Francisco, members of the associations crowded the plaza in front of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s hotel in red caps, waving red banners, and some

assaulted a reporter and Chinese human rights activists.

Two leaders of one association that appeared in one of the March ads, America Changle Association, allegedly ran a

secret Chinese police station in Manhattan’s Chinatown. One of them received a plaque from a Ministry of Public Security official for his work in countering Falun Gong protests while Xi was in Washington in 2015.

People walk by a building (C) that is suspected of being a Beijing-controlled secret police station used to repress dissidents living in the United States, in New York City's Chinatown on April 18, 2023. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Liang Litang, a United Front leader in Boston,

submitted photographs and other details of dissidents to the New York Chinese Consulate and China-based officials under their directions, U.S. prosecutors said.

Entities such as China Press also serve more covert functions for the regime, said Ms. Zhang, the former World Journal editor.

Chinese authorities can send personnel from the mainland to work at these U.S.-based organizations, which are used as a cover, she alleged.

A former senior reporter who retired from a pro-Beijing Chinese newspaper in New York City, who spoke to The Epoch Times under the alias Zhao Wei, confirmed that has happened. She recalled one China Press manager admitting to having been “dispatched over” from China.

“I don’t know how long I can work here,” the person said, according to Ms. Zhao. She suspects that the person was part of China’s intelligence services.

The Epoch Times was unable to independently verify her claims.

Some members of Congress who have examined China Press’s background find it troubling.

Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.), who has pushed for stronger measures to deter Chinese influence operations, introduced a bill in March called “Countering China’s Political Warfare Act” to target United Front groups.

“The China Press was established by the propaganda arm of the Chinese Communist Party, the United Front, to whitewash the CCP’s crimes and human rights abuses,” he told The Epoch Times.

Mr. Banks said the newspaper “should be investigated and punished” for violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act, which requires entities representing foreign interests to make disclosures.

He said that this is how his bill can make a difference: by empowering authorities to “sanction the real owners of the China Press in Beijing for engaging in political warfare against the United States.”

The Epoch Times sent a list of questions to China Press, but didn’t receive a response by press time.

Hannah Cai and Sophia Lam contributed to this report.