We’ve all experienced intuition in some form or another. The hunch of knowing without understanding why; the sense that something is right—or terribly wrong—before conscious thought catches up. Or a simple instinct that something is off about a stranger.

Intuition goes beyond superstition, serving as a sophisticated form of intelligence operating largely beneath conscious awareness.

The phenomenon raises a question that has intrigued scientists, philosophers, and everyday decision makers: Where do gut feelings really come from?

Knowing Without Knowing How

Studies have found that when chess grandmasters are given just five seconds to evaluate a position, they can make accurate predictions despite lacking time for conscious analysis.

Because of the thousands of hours of experience under their belts, their brains can make rapid decisions through pattern recognition, without requiring deliberate thought. This experience, similarly reflected among experts across many fields—doctors, military personnel, and firefighters—points to the possibility that intuition may emerge from a rich substrate of prior experience.

Emma Seppala, psychologist and science director at Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, told The Epoch Times that in these instances, intuition is “a fast, instinctive form of intelligence that operates separately from our conscious thoughts.”

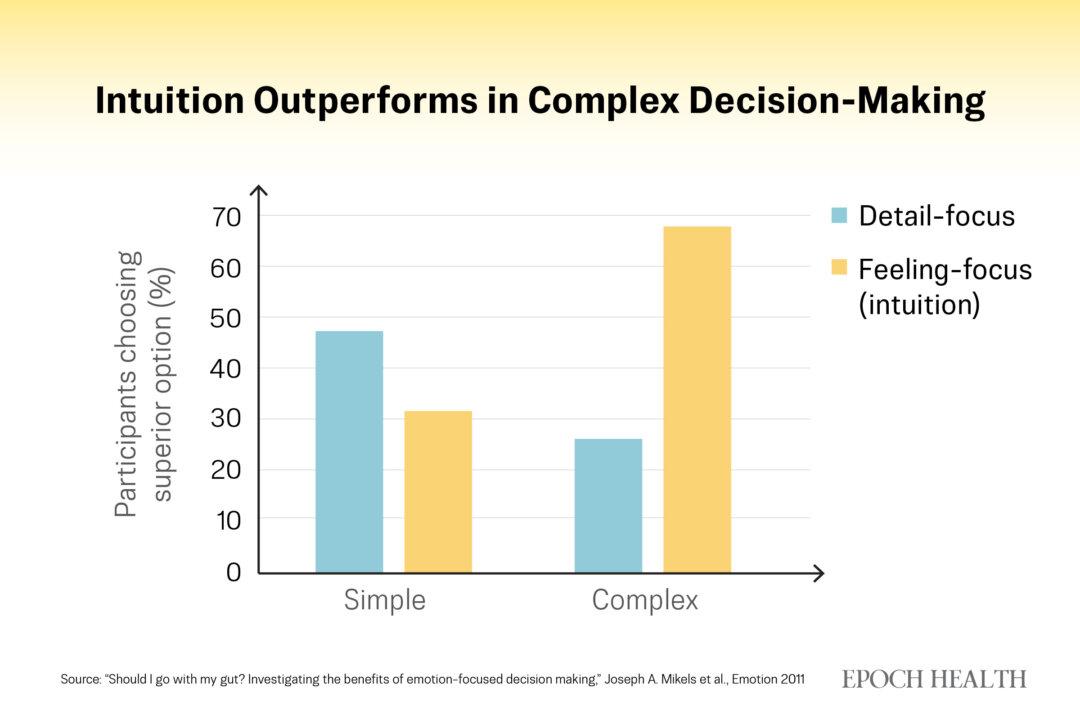

Yet, this kind of intuitive, rapid processing isn’t limited to professional skills. Going with your gut may be especially true in complex situations in your own life. Research shows that when people face complex decisions, such as selecting a home or making major life choices, those who focus on their feelings rather than painstakingly analyzing every detail often make better decisions and, perhaps even more importantly, are more satisfied with the outcome.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times)

Kamila Malewska, a professor who teaches about intuition in managerial decision-making at Poznań University of Economics and Business, believes intuition is invaluable in situations with multiple alternatives, no clear criteria, insufficient information, and unique problems without precedent.

The Biology of Gut Feelings

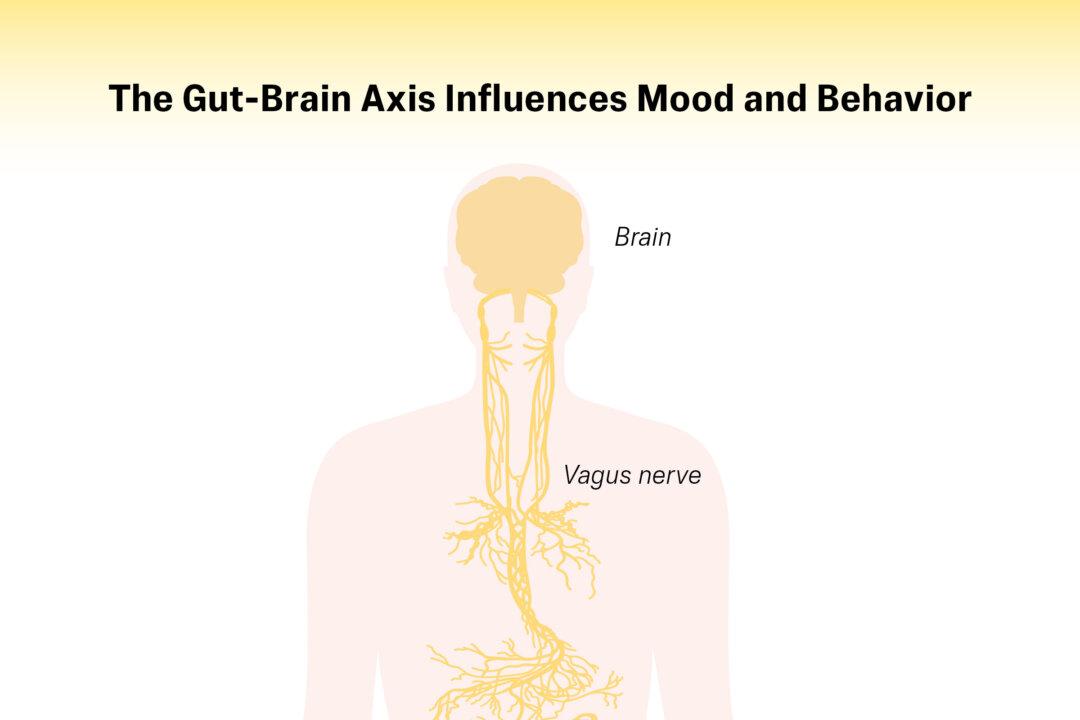

We often say we have a “gut feeling,” and research now shows the phrase carries both a metaphorical and biological truth.

The gut has what scientists refer to as a “second brain,” comprising more than 200 million neurons. These neurons send signals back and forth with the brain through the vagus nerve, forming the gut-brain axis. This system creates a feedback loop that affects how we feel physically and emotionally.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

Moreover, the health of the gut microbiota, which comprises approximately 38 trillion bacteria, can affect feelings of urgency, emotions, and even memory, as it produces chemicals that affect the brain. In mouse experiments, altering the gut microbiota balance can alter brain neurochemistry, making mice more bold or anxious. Notably, in humans, approximately 90 percent of serotonin, a key neurotransmitter that influences mood and decision-making, is produced in the gut. This indicates that emotional states and intuitive feelings may be influenced by the gut-brain axis.

This connection isn’t new. The vagus nerve may have helped our predecessors find food and avoid danger through gut-based intuitive signals. Today, the gut-brain system still functions, albeit in a different manner. When you feel butterflies in your stomach before a big decision, or a sinking feeling when something seems wrong, you may be experiencing this ancient communication system at work.

Unconscious Gestalt

Besides the gut-brain axis, neuroscientists have found other brain processes that may explain intuition.

One way to understand intuition is to examine how memories form.

Don Tucker, a neuroscientist who studies consciousness and memory, says that memory occurs before you are aware of it.

“Memory is organized from an implicit level where general meaning is not fully articulated into conscious access, but is still very powerful in providing a sense of the gist of the information,” Tucker told The Epoch Times.

In other words, before we consciously remember or notice something, our brains, especially our limbic system, rapidly sort out experiences, picking up the important bits and giving a holistic level of understanding.

This process relates to another psychological concept called gestalt: the brain’s tendency to perceive patterns rather than individual parts, and to create closure to make sense of incomplete information.

Your brain completes the triangle. This is Gestalt psychology, in which the mind organizes parts into patterns. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

Consider a manager interviewing a seemingly perfect candidate. His résumé seems impeccable, his answers are satisfactory, but something still feels wrong. Only later does the manager realize the subtle inconsistencies in the candidate’s story, a shift in eye contact during discussions of previous employment, and a mismatch between verbal and nonverbal expressions. The cues may not have been noticed in the moment, but the brain assembled them into an intuitive warning—into an unconscious gestalt.

Neuroscience supports these ideas. The right hemisphere of the brain is good at spotting patterns and noticing things that don’t fit, even if we’re not aware of it. The hippocampus compares what we see now with past experiences, while the orbitofrontal cortex integrates emotional memories with present sensory input. The result appears as a feeling rather than a thought.

The process of unconscious becoming conscious is driven by what is called predictive processing.

Rather than passively receiving stimuli and then reacting, predictive processing theory suggests that the brain actively generates predictions about what it should perceive based on its experience. When these predictions detect a mismatch—something that does not fit the expected pattern—the result manifests as intuitive unease or “knowing.”

According to Tucker, consciousness develops from this primitive, intuitive level through a process of articulation. A vague feeling—a sense of “No, I shouldn’t do that”—gradually becomes more conscious and explicit as the brain works to understand why the feeling arose.

Could intuition also come from somewhere else?

Perhaps, instead of merely reacting to the present, intuition offers us a glimpse of the future.

Memories From the Future

In the mid-1990s, Dean Radin at the University of Nevada–Las Vegas designed an experiment to test whether awareness could transcend time. He had participants connected to an EEG machine and placed in front of a computer screen. The computer randomly selected and displayed pleasant or disturbing images after a brief pause.

Radin noticed that people’s brains became more active just before seeing disturbing images, but not before positive ones. It was as if the brain could sense something bad was coming, even seconds before it happened. This effect was called “presentiment.”

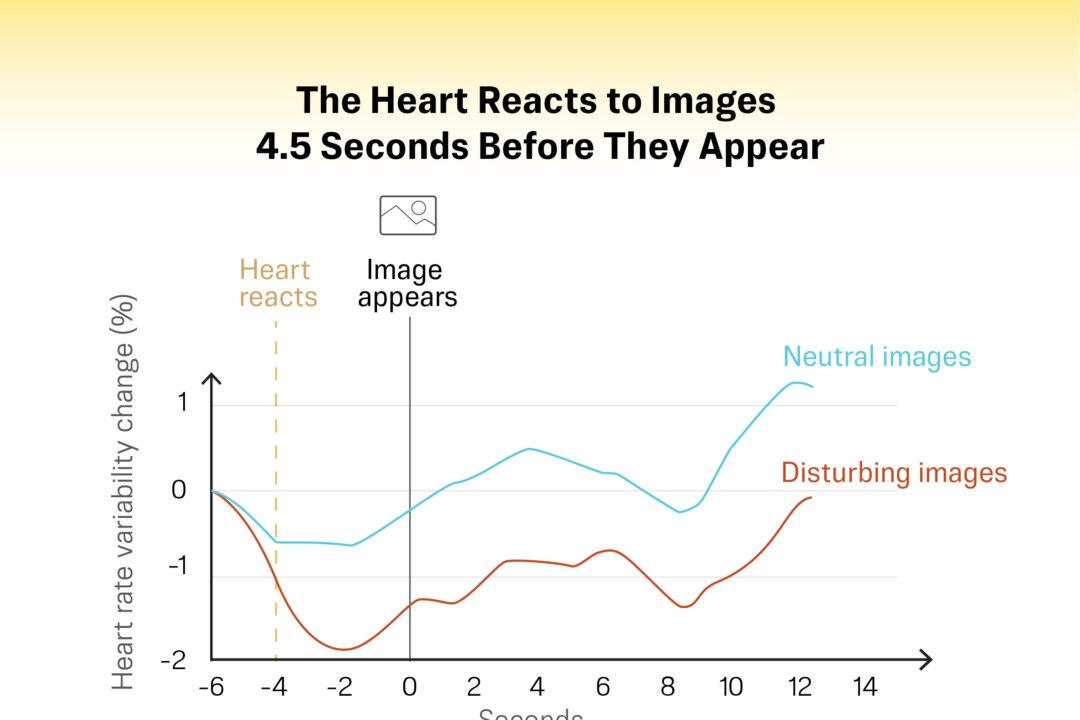

Replicated results following Radin’s original experiment. Lower heart rate variability in response to disturbing images indicates a stronger fight-or-flight reaction. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

The results were statistically significant, and other researchers, such as Daryl Bem at Cornell University, found similar effects in their own experiments.

A 2012 meta-analysis of 26 studies spanning three decades found that experiments such as Radin’s and Bem’s suggest that human physiology can distinguish between randomly delivered emotional and neutral stimuli occurring one to 10 seconds in the future.

This isn’t precognition in the traditional sense—a psychic power of seeing future events—participants aren’t consciously predicting them. Instead, their autonomic nervous systems—heart rate, skin conductance, and brain activity—show measurable arousal before encountering emotionally significant stimuli. According to the 2012 meta-analysis, the effect size may be small. Still, it’s statistically significant across multiple laboratories and researchers, with the probability of the effect being a coincidence estimated at one in a trillion. That’s the equivalent of flipping a coin and getting heads 40 times in a row.

Julia Mossbridge at Northwestern University, who led the meta-analysis, said when the study was released: “The phenomenon is anomalous, some scientists argue, because we can’t explain it using present-day understanding about how biology works.”

Nevertheless, intuitive presentiment is increasingly researched and recognized.

Seppala said there is a real advantage to developing the “cognitive faculty” of intuition, as evidenced by cases of soldiers surviving only because of their “hunches.” The military, as a consequence, has invested significant resources in developing and understanding the “sixth sense,” or what the U.S. Office of Naval Research calls “spidey sense.” In 1995, even the CIA declassified its own research on precognition.

Eric Wargo, a researcher exploring precognition, told The Epoch Times that intuition represents a fundamental feature of how living things respond to their environment and thus shouldn’t be called a “sixth sense,” but rather the “first sense.” He suggested that the ability could be rooted in the brain’s microtubules, which, through quantum processes, might allow information to move not just from past to future, but from future to past.

“Precognition, I believe, is intuition by another name,” Wargo said, calling it potentially “one of the first guidance systems in the simplest living organisms.”

“There’s something more going on than what current neuroscience can explain,” he said.

Becoming More Intuitive

Whether intuition comes from the brain, the gut, or something more mysterious, researchers generally agree on a few practical points.

Firstly, intuition can be developed. “We can think of it as a separate form of cognition that has been neglected in our education,” Seppala said. “We prioritize rationality over intuition, innovation, and creativity—but we are now seeing a creativity crisis in our young people because these skills are not nurtured the way logic and rationality are. Since it’s a cognitive faculty, it is something that can be trained.”

Wargo suggests that building intuition begins with paying attention, and it can be developed through practicing mindfulness. “Modern humanity has lost its connection to the environment,” he said, “not just natural surroundings but also paying attention to where you are, what you are, who you are, what you’re doing.”

Second, intuition needs discernment—to distinguish genuine intuition from fear, bias, or wishful thinking—which requires self-awareness. “Otherwise, you don’t know whether it is a fear or an intuition that is guiding you,” Seppala said.

Third, integrate both intuition and rational thinking.

Intuition is not infallible. “It is not easily verified and therefore can be wrong,” Tucker said. It is also an early level of gaining knowledge. Therefore, rational analysis is necessary.

Malewska’s research echoed this balance: Purchasing managers get the best results when they blend rational analysis with intuition.

The most effective decisions come not from gut feelings alone or pure logic, but from the conscious interplay between the two.