In an August outbreak in the New York City neighborhood of Harlem, seven people died and more than 100 were sickened by Legionella pneumophila, a waterborne bacterium spread through inhaled mist.

The main source: a cluster of 12 hospital cooling towers.

However, this isn’t just a New York City story.

Nearly a decade ago, during the height of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, national attention focused on lead contamination. Behind the scenes, scientists uncovered a second public health emergency: a parallel outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease that killed at least a dozen people.

“It always comes from a contaminated water source,” Michele Swanson, a microbiologist at the University of Michigan Medical School who investigated the Flint outbreak, told The Epoch Times.

Her team’s analysis revealed that chlorine levels in Flint’s water supply had dropped significantly during the crisis, creating ideal conditions for Legionella to thrive.

First identified nearly 50 years ago, the disease takes its name from a 1976 outbreak that sickened more than 200 attendees at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia. It offered the public a first look at a pneumonia that spreads not from person to person, but through microscopic droplets of contaminated water vapor.

Now, nearly five decades later, reported cases are on the rise.

What Is Legionnaires’ Disease?

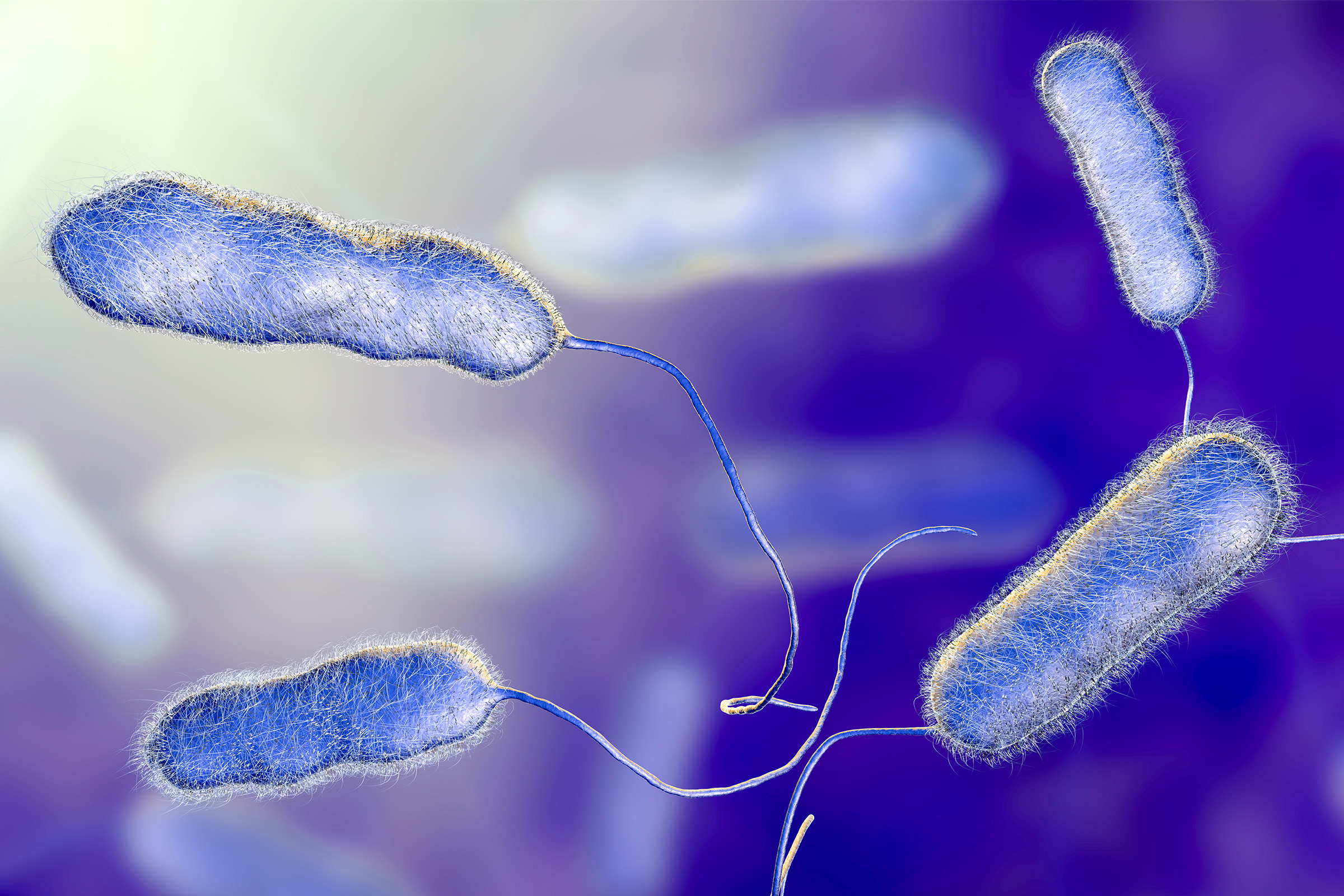

Legionnaires’ disease is a serious, sometimes fatal form of pneumonia caused by Legionella, a bacterium that thrives in warm, stagnant water and spreads through airborne mist.

Unlike other respiratory infections, it doesn’t pass from person to person. Instead, people contract the disease by inhaling microscopic droplets of contaminated water, often from human-made systems such as cooling towers on hospitals or high-rises, decorative fountains, hot tubs, or construction spray systems.

“We don’t share Legionella with each other,” Swanson said. “In these large buildings, it’s often a cooling tower—basically a pond sitting on top of the building. If wind blows across, it can send aerosol into an air conditioning system or out into the surrounding area.”

Once inhaled, Legionella operates very differently from most pneumonia-causing bacteria. Rather than being destroyed by immune cells in the lungs, it invades and replicates inside them, making it harder to treat and more dangerous for vulnerable people.

“It becomes what’s called an intracellular pathogen,” Dr. Paul Auwaerter, clinical director of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told The Epoch Times. “If people become ill enough to be hospitalized, it has a mortality rate that can range from 15 to 25 percent—so it’s pretty significant.”

Why Legionnaires’ Keeps Coming Back

Both Auwaerter and Swanson noted that cases tend to spike in late summer and early fall, when rising temperatures drive up use of cooling systems such as air conditioning towers and misting stations.

However, despite improved awareness and treatments, Legionnaires’ disease rates are rising, particularly in older, densely built cities such as New York City.

“If you’re in a high-density area with high-rise buildings and so on, you see it more,” Auwaerter said.

The bacterium’s remarkable resilience makes eradication challenging. Swanson, whose lab studies Legionella’s behavior inside buildings, said the bacteria often establish themselves by forming biofilms.

“It doesn’t just grow as a free-floating bacterium,” she said. “It grows in communities on pipe surfaces and covers itself with this kind of slimy layer, which holds the community together and makes it more difficult to get biocides or antibiotics to cross that slimy layer and get into where the bacteria are growing to kill them.”

Even aggressive efforts to “shock” contaminated systems with heat or chemicals sometimes fail. In one case, Swanson said, a long-term care facility had to be demolished after repeated efforts to eradicate Legionella were unsuccessful.

“Engineered water systems create the opportunity,” she said. “And if not properly managed, they give Legionella the perfect conditions to flourish. Once a building is colonized, it can be very hard to eradicate.”

Key prevention measures include:

- Keeping hot water heaters hotter than 140 degrees Fahrenheit

- Preventing water stagnation in plumbing systems

- Monitoring disinfectant levels

- Regularly inspecting cooling towers and dead-end pipes

Recognizing the Signs

At first glance, Legionnaires’ disease can resemble other forms of pneumonia, with fever, cough, and shortness of breath. However, certain symptoms set it apart:

- Respiratory Symptoms: High fever, often higher than 104 degrees Fahrenheit; chills; shortness of breath; chest pain; and cough, with or without mucus or blood

- Distinguishing Signs: Nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and confusion or difficulty concentrating

- Additional Symptoms: Muscle aches, headaches, fatigue, and seizures—rarely

Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are the early signs more common in Legionnaires’ than in other pneumonias.

Confusion or trouble concentrating can also appear in early stages—atypical for most lung infections—and may suggest that the bacteria are affecting more than just the lungs.

While most healthy people can recover with prompt care, certain groups are far more vulnerable to severe illness or complications:

- Adults older than 50

- Smokers or people with chronic lung conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- People with weakened immune systems due to conditions such as cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, or immunosuppressive medications

- Recently hospitalized patients or those recovering from surgery

People who have recently been exposed to cooling towers or who have recently traveled or been hospitalized should be especially alert to these signs, Auwaerter said.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Because its symptoms closely resemble other types of pneumonia, Legionnaires’ is often misdiagnosed unless doctors specifically test for it, Auwaerter said.

“With any disease in the U.S.—Legionella, Lyme, [tuberculosis]—we’re only capturing a fraction of actual cases,” he said. “We track trends, but many people are treated for pneumonia without ever being tested for Legionella.”

Diagnosis typically includes a urine antigen test, which detects the most common Legionella strain.

However, in some hospitals, sputum may be collected for culture or PCR testing to identify the presence of a broader range of Legionella strains. Blood tests and chest X-rays can be done to assess the severity of the pneumonia.

Because the bacteria live inside immune cells, the disease requires targeted antibiotics—typically macrolides or fluoroquinolones—that can penetrate the cells.

“You need antibiotics that can actually get into the white blood cells,” Swanson said.

Auwaerter said: “You also need your body’s immune system to respond [to the infection]. That is why those over age 50, smokers, or people with chronic lung disease or weakened immune systems are at highest risk for serious illness or death.”

Left untreated, Legionnaires’ disease can lead to respiratory failure, kidney failure, or septic shock, especially in people with underlying health conditions.

Any physician who diagnoses a case should report it to public health authorities. This is a requirement in New York City. Reporting helps officials trace sources and prevent future outbreaks, according to Auwaerter.

“I’ve been impressed with New York City’s really proactive policy to address this issue,” Swanson said. “So the good news is that it can be prevented with good water management practices.”

It’s about keeping the conditions hostile to Legionella and not giving it a warm, wet place to grow, she said.