- Cervical: The cervical spine consists of seven vertebrae in the neck. These are small and allow the neck to be mobile.

- Thoracic: The thoracic spine has 12 vertebrae in the upper and mid-back, each attached to ribs, providing strength and stiffness.

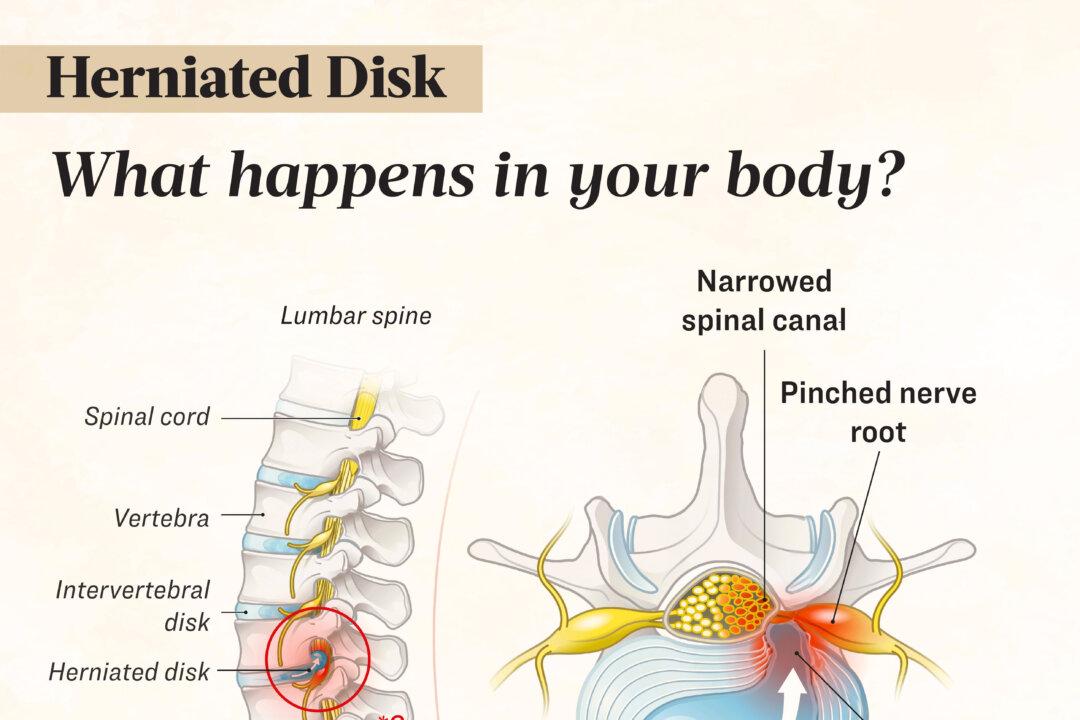

- Lumbar: The lumbar spine, typically with five vertebrae (but can vary between four and six), is the largest and most mobile, bearing significant force and commonly affected by degenerative issues such as herniated disks.

- Sacrococcygeal: The sacrococcygeal region at the spine’s base consists of the fused sacrum (five vertebrae) and coccyx (four vertebrae) and is connected to the pelvis. Variations may include a disk between the first and second sacral vertebrae or fusion of the fifth lumbar vertebra to the sacrum.

A herniated disk can occur in the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine. Lumbar spine herniation is most common, followed by cervical. These areas experience higher rates of disk herniation because they experience greater biomechanical forces.

- Posterolateral disk herniation: The disk usually bulges out to the side and slightly backward into the spinal canal, pressing on the nerve below the affected disk as it travels toward its foramen (exit point).

- Central (posterior) herniation: This less common type involves disk protrusion directly posteriorly. If it occurs around the fifth lumbar vertebra (usually L4-5 or L5-S1), it may compress the nerve roots or cause cauda equina syndrome, which most often occurs due to a large herniated disk in the lumbar region and involves severe back and leg pain along with loss of bladder control.

- Lateral disk herniation: In this case, the nerve root compression occurs at the same level as the herniation.

- After sitting or standing

- At night

- While sneezing, coughing, or laughing

- While bending backward or walking for long distances

- While holding your breath or straining, such as during a bowel movement

The pain and other symptoms often diminish or improve significantly over the course of weeks to months.

Cervical

A cervical herniated disk can compress spinal nerves or, in severe cases, the spinal cord, leading to various symptoms. Nerve compression may cause pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in the neck, shoulders, chest, arms, or hands. Pain might worsen with neck movement and may radiate to the shoulder blade, upper arm, forearm, or fingers. Severe herniation can affect the spinal cord, leading to leg weakness, stiffness, or difficulty with bowel and bladder control.

Thoracic

Symptoms and signs of a herniated thoracic disk, the rarest type, may include radiculopathy and myelopathy.

Lumbar

A herniated disk in the lower back can cause various symptoms, including:

- Lower back pain: This is marked by intermittent or continuous pain at the site of the herniated disk.

- Sciatica: This sharp, shooting pain radiating from the buttocks down the leg is caused by pressure on the sciatic nerve.

- Leg or foot weakness: This results from the herniated disk pressing on nerves that control the legs or feet.

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction: In rare cases, pressure on nerve roots can lead to issues with bowel and bladder control, requiring immediate medical attention.

- Additional symptoms: Other symptoms may include muscle spasms, muscle weakness, numbness, impaired reflexes, difficulty walking, and incoordination.

1. Age-Related Degeneration

The most common cause is degeneration, in which the nucleus pulposus dehydrates and weakens with age. As a result, intervertebral disks lose water and their ability to cushion the vertebrae, becoming less flexible. This makes the outer layer of the disk more prone to rupture or tearing. This degeneration can gradually lead to disk herniation and associated symptoms.

2. Trauma, Improper Lifting, and Surgery

Trauma or injury due to improper lifting of heavy objects can also cause a herniated disk. A disk may herniate due to a sudden traumatic injury or the accumulation of repeated minor injuries. Acute disk herniations can occur in young, healthy individuals due to an injury or tear in the annulus fibrosus, allowing the nucleus pulposus to protrude into the spinal canal or foramen.

3. Genetics

Research has found that genetic variations, particularly in collagen-related genes, can increase the risk of intervertebral disk disease by weakening disk stability and promoting degeneration. Variants in immune-related genes may also contribute by triggering inflammation and dehydration of disks, accelerating their degeneration. Additionally, genetic changes affecting the development and maintenance of disks and vertebrae are linked to disk degeneration and herniation.

- Bulging: The outer edge of the disk extends beyond the borders of the vertebrae above and below it.

- Protrusion: The inner gel-like core of the disk pushes against the annulus fibrosus without breaking through, while the ligament at the back of the spine remains intact.

- Extrusion: The disk’s inner core breaks through the outer layer but is still contained by the ligament at the back of the spine.

- Sequestration: The inner disk material not only breaks through the outer layer but also ruptures the ligament at the back of the spine, with a portion of the disk moving into the space near the spinal cord.

- Age: Herniated disks are more common in middle-aged and older people (30s to 50s), often following strenuous physical activity. After age 50, the inner portion of the disk starts to harden, reducing the risk of herniation.

- Family history of herniated disks: Research suggests that a tendency for herniated disks may run in families with multiple affected members. Two studies found that a positive family history of herniation increases the risk of herniation in adolescents by about five times.

- Diabetes: Diabetes can also increase the risk of herniated disks. One study involving only female participants found that diabetes increased the risk of herniation by about 50 percent.

- Cardiovascular problems: Cardiovascular problems, particularly atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, have been associated with an increased risk of herniation.

- Lifting heavy objects: Using the back muscles instead of the legs to lift heavy objects or twisting while lifting can lead to a herniated disk. Lifting with the legs helps protect the spine.

- Repeatedly bending or twisting the lower back: Physically demanding jobs often involve lifting, pulling, bending, or twisting. Using proper lifting and movement techniques can help protect the back.

- Athleticism: For instance, weightlifters, rowers, and American football players have a higher risk of disk herniation.

- Congenital and connective tissue disorders: Connective tissue disorders can make one more prone to developing a herniated disk. One example is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a group of inherited disorders characterized by unusually flexible and fragile connective tissue. Each vertebra has two pedicles, bony projections that protect the spinal cord and nerves on the sides. Having short pedicles can also make one more prone to disk herniation.

- Lack of physical activity: A sedentary lifestyle can weaken the muscles supporting the spine, increasing the risk of injury. Additionally, sitting for extended periods can place pressure on the spine and disk. Long-haul truckers and taxi drivers are at greater risk.

- Smoking: Smoking is thought to reduce the oxygen supply to the disk, leading to faster degeneration. Smoking fewer than five cigarettes a day increases the risk of herniation by about 20 percent while smoking 45 or more a day doubles the risk.

- Poor posture: Poor posture while sitting or standing can put added pressure on the spine, thus contributing to disk degeneration and herniation.

- Obesity: Carrying excess weight places additional pressure on the disk in the lower back.

- Neurological exam: A neurological exam helps determine if nerve damage is causing symptoms, as nerves affect muscles in predictable patterns, with absent reflexes or altered sensations potentially indicating a herniated disk compressing a nerve. It involves tests such as checking lower leg muscle strength by having the patient walk on heels and toes, testing reflexes at the knee and ankle, and checking for sensory loss by lightly touching legs and feet.

- Straight leg raise (SLR) test: The SLR test helps diagnose a herniated disk, especially in younger patients. The patient lies on their back while the doctor lifts the affected leg. If they experience pain down their leg and below the knee, it strongly suggests a herniated disk.

- Lumbar spine examination: The lumbar spine exam includes assessing the range of motion by having the patient bend forward, backward, and rotate the spine. The evaluation also involves observing standing and sitting postures.

Diagnostic Tests

The following diagnostic tests may also be performed:

- Flexion-extension X-rays: A flexion-extension X-ray, taken while the patient bends forward and backward, provides more detailed information about vertebral instability than a traditional X-ray.

- Three-foot standing X-rays: A three-foot standing X-ray, available in anterior–posterior and lateral views, uses large films to capture detailed images of spinal alignment, which may be disrupted by a herniated disk.

- MRI: An MRI provides a detailed view of the vertebrae, disks, surrounding soft tissues, spinal cord, and affected nerves.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: A CT scan may be recommended for individuals with a history of spinal injury or surgery or when a herniated disk is suspected to result from another spine condition, as it offers more detailed imaging than a standard X-ray.

- Electromyogram (EMG): An electromyogram can help identify nerve compression caused by a herniated disk by measuring electrical impulses in nerves, nerve roots, and muscles. By inserting thin electrodes into specific muscles and observing their responses during movement, doctors can pinpoint affected nerve roots and assess nerve-related muscle damage.

- Myelography: Myelography involves injecting a contrast dye into the spinal column, followed by X-rays and a CT scan, to visualize indentations in the spinal fluid sac caused by herniated disks. This procedure helps determine the size and location of a herniated disk.

- Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) test: The NCV test measures how quickly electrical signals travel along a nerve. For herniated disk diagnosis, this test can help determine if a compressed or damaged nerve is affecting its ability to transmit signals efficiently. During the test, small electrodes are placed on the skin over the nerve, and a mild electrical impulse is sent through the nerve. It is usually used alongside EMG.

- Bone density tests: These assess the quality and strength of bones.

- Chronic back or leg pain

- Loss of movement or sensation in the legs or feet

- Loss of bowel or bladder control

- Permanent spinal cord damage (very rare)

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Permanent nerve damage

- Paralysis (very rare)

- Death (very rare)

1. Medication

Treatment starts with the most minimally invasive options, such as medications. The commonly used ones include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Pain from a herniated disk can result from nerve and tissue inflammation near the affected area. Swollen nerves may press against the disk, causing discomfort. NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin can reduce inflammation, alleviate swelling, and relieve pain, making them useful for long-term pain management.

- Muscle relaxants: Muscle relaxants can reduce spasms and alleviate pain, improving mobility. Doctors typically prescribe these medications for a short duration (e.g., one to two weeks), as pain from muscle spasms often resolves naturally over time.

- Corticosteroids: If other treatments fail to relieve pain, a doctor may prescribe oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone and methylprednisolone), which reduce inflammation near the herniated disk, ease nerve pressure, and alleviate pain. Corticosteroid injections are a second-line treatment, typically used when other treatments have not provided pain relief. These injections, delivered into the epidural space around the spinal cord, reduce inflammation and can provide relief for several months. While they may alleviate symptoms, they do not address the underlying issue, and pain may return over time. The different types of injections include epidural steroid injections, nerve root blocks, facet joint injections, and sacroiliac joint injections.

- Narcotics: Narcotics may be used if the pain is severe and doesn’t respond to NSAIDs.

2. Rest and Lifestyle Changes

Many health care providers recommend reducing or modifying activities, suggesting taking frequent rest breaks, avoiding sitting for too long, and moving slowly and steadily when bending or lifting. A patient may gradually return to normal activities after two to three weeks and avoid heavy lifting or twisting for the first six weeks. If the person is overweight, focusing on diet and exercise may help.

- Bend knees and hips, keeping the back straight when lifting.

- Carry objects close to the body.

- When standing for prolonged periods, rest one foot on a small stool or box.

- When sitting for prolonged periods, elevate the feet on a stool so the knees are higher than the hips.

- Avoid wearing high-heeled shoes.

3. Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is also a first-line treatment like medications but is not advised immediately, as most disk herniation symptoms improve within a few weeks.

4. Surgery

Only a small percentage of patients with herniated disks need surgery, which is the last resort. The goal of surgery for a herniated disk is to remove damaged disk tissue and stabilize the spine, and it is performed under general anesthesia. There are different types of surgery, including:

- Diskectomy: Diskectomy is the most common surgery for a herniated disk. It involves removing the damaged part of the disk to relieve pressure on the affected nerve. This may be done through an open procedure with an incision for direct access to the disk.

- Artificial disk replacement: Surgeons increasingly recommend artificial disk replacement as an alternative to spinal fusion for younger patients. The artificial disk, a prosthetic spacer, replaces the removed herniated disk and helps preserve spinal flexibility and stability without the need for screws or plates. This option may offer better long-term results and fewer complications than fusion. The procedure involves removing the herniated disk, inserting the artificial disk, and closing the incision with stitches.

- Spinal fusion: If a disk has slipped significantly or surrounding vertebrae and joints can no longer support the spine, spinal fusion with diskectomy may be performed, more commonly in the neck than the lower back. The procedure involves removing the damaged disk and herniated fragments, then permanently joining the vertebrae above and below the disk space to stabilize the spine and eliminate movement between the vertebrae.

5. Other Therapies

Additional therapies may be recommended, including:

- Spinal manipulation: Chiropractic adjustments or osteopathic manipulations can help alleviate pain and enhance function in the back or leg, especially in cases of sciatica.

- Hot and cold therapy: Heat therapy helps relax tight muscles, increase blood flow, and reduce spasms, while cold packs can reduce inflammation and relieve pain.

- Traction therapy: Traction involves applying a stretching force to vertebrae using body weight, weights, or pulleys to separate the joints of the spine. Research shows that traction therapy can positively affect pain, disability, and straight leg raising in patients with intervertebral disk herniation.

- Cryotherapy: Cryotherapy helps reduce muscle spasms and inflammation during acute herniation cases.

1. McKenzie Method

The McKenzie method, or mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT), is a widely accepted approach for treating back pain. It focuses on self-treatment through posture correction and frequent, end-range exercises to relieve symptoms and improve mobility.

2. Tuina (Manual Therapy)

Traditional Chinese manual therapy, Tuina, uses rolling, pinching, and diagonal pulling techniques to relax muscles, improve circulation, regulate spinal balance, and reduce swelling. By affecting skin, muscles, meridians, acupoints, and joints, it helps treat conditions like lumbar disk herniation and other disorders.

3. Acupuncture

As per a 2018 meta-analysis, acupuncture demonstrated greater effectiveness in treating lumbar disk herniation than lumbar traction, various medications (e.g., ibuprofen, diclofenac sodium, meloxicam, mannitol with dexamethasone, mecobalamin), and a few Chinese herbal remedies.

4. Meditation

A 2023 meta-analysis of 12 studies involving 1,005 participants suggested that meditation might be effective in reducing short-term pain intensity in patients with low back pain. A 2022 meta-analysis of 12 studies involving 1,153 participants also found meditation-based therapy to be a safe and effective alternative method for managing chronic low back pain.

Promising Animal Studies

The following is an example of promising research in animals that may eventually help with the condition, but more research is needed to confirm its effectiveness.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Exercise regularly to strengthen and stretch core muscles. Perform specific core-strengthening exercises (e.g., pelvic tilts and abdominal curls) and stretching exercises (e.g., knee-to-chest stretch) to stabilize the spine and decrease disk strain. Incorporate aerobic exercises to improve overall fitness.

- Practice proper lifting techniques to avoid injury.

- Maintain good posture.

- Avoid repetitive movements that strain the back.

- Treat medical conditions that may increase the risk of disk herniation.

- Avoid smoking.

- Practice yoga: A 2010 study showed that a group of long-term yoga practitioners had significantly less degenerative disk disease than a group that didn’t practice yoga.

- Take breaks to walk around if sitting for prolonged periods (at least once every hour).

- Consider using back braces: Some health care professionals may recommend using back braces to help support the spine and prevent injuries if you lift heavy objects at work. However, some research suggests back braces are not associated with few back injuries or less lower back pain. Additionally, overreliance on braces can weaken spinal support muscles over time.