Pulmonary (PTB)

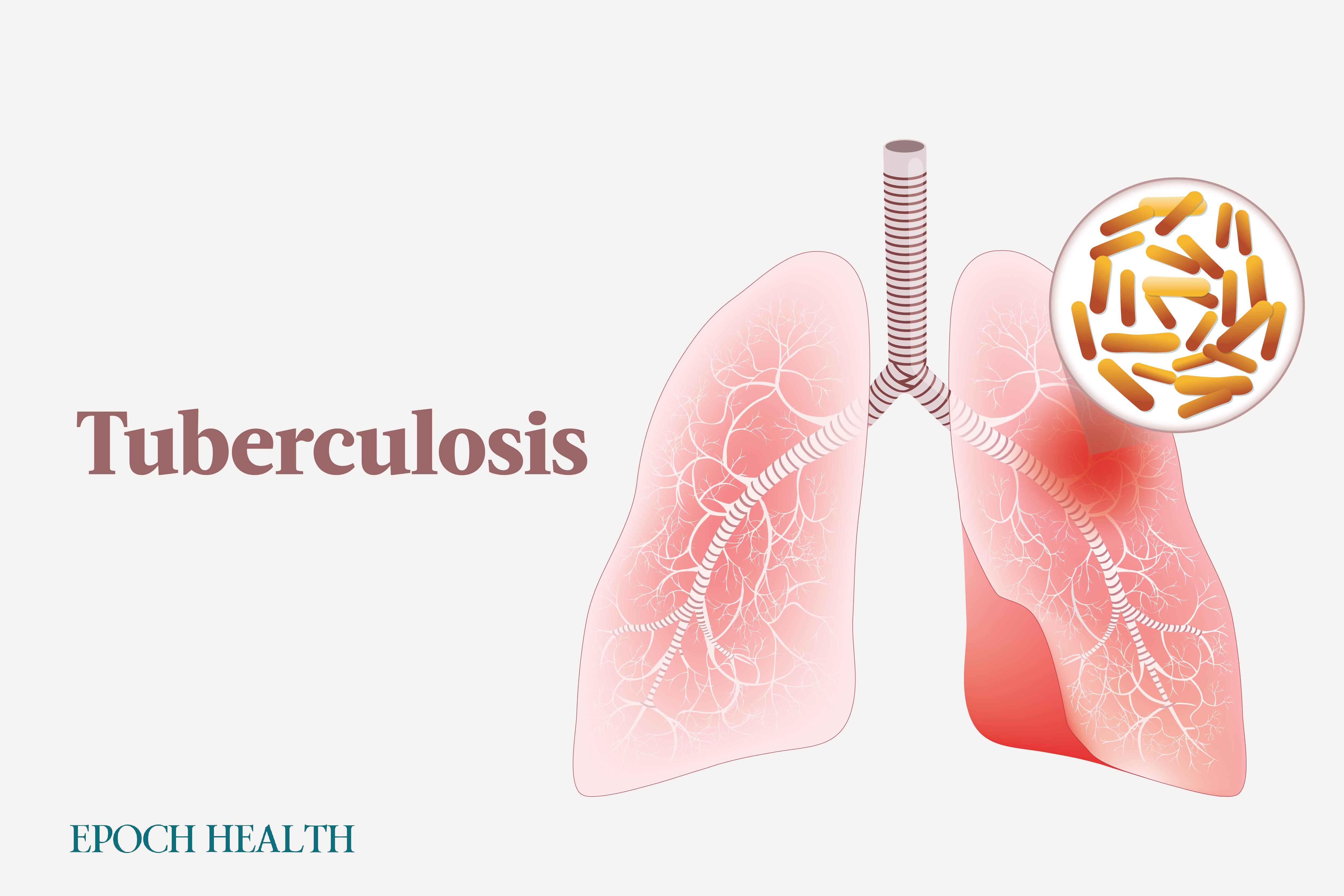

Pulmonary TB (PTB) is an infection involving the lungs but can also spread to other organs.

Extrapulmonary (EPTB)

Extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) stands for tuberculosis that originates in organs outside the lungs and never involves the lungs. If TB originates outside the lungs and eventually moves to the moves, it is then considered PTB. In 2021, 1,780 cases of EPTB were reported in the United States, accounting for almost 23 percent of the total cases. EPTB often arises from the spread of infection through the bloodstream or direct extension from nearby organs. Fortunately, individuals with EPTB do not generally transmit the disease to others.

- TB lymphadenitis: TB lymphadenitis is the most common form of EPTB, and it typically affects lymph nodes in the posterior neck and collarbone.

- Skeletal: Bone and joint tuberculosis can account for up to 35 percent of EPTB cases. The spine is the most commonly affected, with tuberculous arthritis in weight-bearing joints following in frequency. Pott’s disease, or spinal TB, frequently affects the thoracic spine. It starts in a vertebral body and commonly spreads to adjacent vertebrae, narrowing the disk space.

- Miliary: Also called generalized hematogenous TB, miliary TB results from the spread of TB lesions into blood vessels, disseminating millions of bacilli throughout the body, with the lungs and bone marrow being common sites.

- Pleural: In the United States, pleural TB comprises approximately 5 percent of all TB cases and is one of the most common types of EPTB. Pleural TB affects the pleura, the thin membrane lining the chest cavity and covering the lungs.

- Meningeal (TB meningitis): TB meningitis is the most severe form of TB, with high mortality. It often occurs independently of infection at other extrapulmonary sites.

- Abdominal: Abdominal TB can affect abdominal organs such as the kidneys, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and the peritoneum (the membrane encasing abdominal organs). Genitourinary TB infects the kidneys and can extend to the bladder and, in men, to the prostate, seminal vesicles, and epididymis (the coiled tube that stores and transports sperm). Peritoneal TB occurs when the infection spreads within the abdominal cavity’s lining from abdominal lymph nodes or an inflamed ovary and fallopian tube. Gastrointestinal TB can occur through various means, such as consuming contaminated food, via bloodborne spread, or from neighboring organs. Intestinal lesions can take the form of ulcers (most common), excessive growth, or a combination of both. Although liver involvement by TB is typically clinically silent, it is common in patients with advanced pulmonary TB or miliary TB. The liver generally heals without sequelae if the primary infection is treated.

- Cutaneous: Also known as scrofuloderma, cutaneous TB occurs when an underlying TB infection spreads to the skin, causing the formation of ulcers and sinus tracts.

- Pericardial (TB pericarditis): Pericardial TB starts as an infection of the covering of the heart (pericardium) and can arise from mediastinal (chest cavity) lymph nodes or pleural TB.

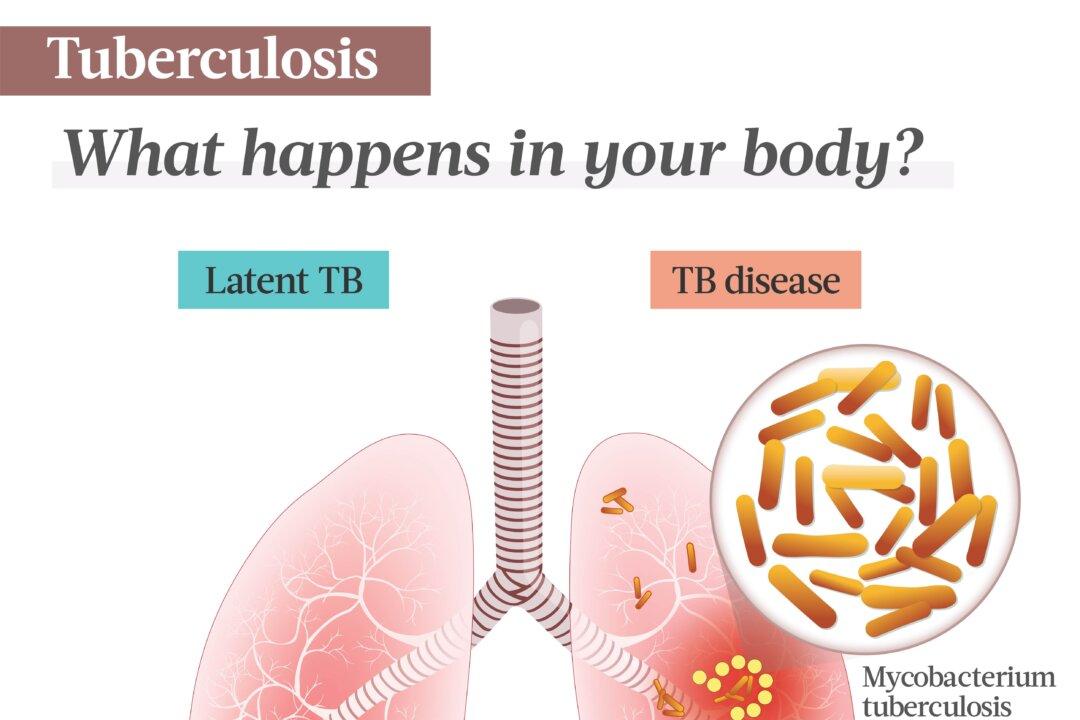

- Active: Also known as TB disease or primary progressive tuberculosis, around 10 percent of individuals infected with TB will develop an active symptomatic infection. Some may suffer from the spread to distant organs.

- Latent: Latent TB takes place when an individual infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis doesn’t develop TB disease. As long as they are latent, individuals cannot spread bacteria to others. However, they may develop active TB in the future. Treatment is often prescribed to prevent this.

- Postprimary: Also called secondary TB or reactivation TB, postprimary TB is the second and most common form of active TB, accounting for 90 percent of cases. In postprimary TB patients, the disease often develops from either the reactivation of a latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection or external reinfection by the same bacterium. Reactivated TB can develop years after the initial infection, and for those without coexisting health issues, there is a 5 percent to 10 percent lifetime risk of developing active TB.

- Chills.

- Fever.

- Profuse night sweats.

- Weight loss.

- Loss of appetite.

- Malaise.

- Weakness.

- Fatigue.

- Poor growth in children.

Symptoms depending on affected organs include the following:

- Pulmonary: difficulty breathing, chest pain, persistent cough lasting over three weeks, coughing with mucus and/or blood, profuse night sweats, fatigue, fever, weight loss, swollen glands, and sore throat.

- Lymphadenitis: swollen lymph nodes. In advanced cases, nodes may become inflamed and tender, potentially forming a draining fistula (an abnormal connection between internal body parts). Enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes is also common in primary pulmonary disease.

- Skeletal: persistent pain in the affected bones and chronic or subacute arthritis, neurologic deficits (e.g., paraplegia), paraspinal abscess, and potentially collapsed vertebrae. Articular TB is a slow-progressing monoarthritis affecting the hip or knee. Symptoms include persistent pain, joint swelling, reduced range of motion, and draining sinuses and abscesses. Abscesses can form, resulting in pain or compression of the spinal cord, causing paralysis.

- Miliary: fever, chills, malaise, progressive shortness of breath, fever of unknown origin due to intermittent bacilli dissemination, and possibly anemia and low platelet count.

- Pleural: acute illness with symptoms such as cough, chest pain, fever, and shortness of breath.

- Meningeal: low-grade fever, behavioral and mental changes, persistent headache, nausea, drowsiness, stupor, and coma.

- Genitourinary: painful urination, blood in the urine, and flank pain. It may present as a kidney infection, characterized by symptoms including fever, back pain, and pus in the urine.

- Cutaneous: ulcers, especially on the hands, buttocks, elbows, feet, or knee hollows, that can appear wart-like, flat and painless, brownish-red or purple, or like sores.

- Peritoneal: fatigue, abdominal pain, tenderness, fluid buildup in the belly, and fever.

- Pericardial: pericardial friction rub, chest pain, and fever.

- Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, fever, black stool, rectal bleeding, and abdominal tenderness.

- Liver: enlarged liver, fever, respiratory symptoms, abdominal pain, weight loss, enlarged spleen, fluid buildup in the belly, and jaundice.

- Individuals in close contact with infected people: Since close and lengthy contact is required for TB transmission, the highest risk is for individuals residing in the same household with a person with TB.

- People living in or visiting certain countries: Most TB cases occur in low- and middle-income countries, with half concentrated in eight nations: Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, and South Africa, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

- Older people: Older individuals may be more vulnerable to TB due to weakened immune systems.

- Immunocompromised: These people receive treatments that weaken their immune system, such as chronic immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., steroids), TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy, or organ transplantation, or have medical conditions such as HIV/AIDS, rheumatic diseases, or primary immunodeficiency disorders. TB is the primary cause of death among individuals with HIV.

- Children under 5.

- Diabetics.

- Malnourished people.

- Homeless people.

- Substance users and those who share needles.

- People residing in group settings: These places include nursing homes, correctional facilities, and other places where people live in close quarters.

- Health care workers: Health care professionals who come into contact with people infected with TB and/or high-risk populations are at an increased risk.

- People with high-risk occupations: Miners and construction workers can be exposed to silica dust in their line of work, which can increase TB risk.

- Alcohol abusers and smokers: Individuals who abuse alcohol or smoke may have compromised immune systems.

- Strict vegans or vegetarians: In an older TB study in south London among Asian immigrants from the Indian subcontinent, Hindu Asians (lacto vegetarians who consume dairy products but no meat or eggs) showed an 8.5-fold increased risk for TB compared to Muslims (meat and fish eaters). The study found an increased risk with decreasing meat or fish consumption, possibly due to vitamin D deficiency, which negatively affects the immune system. However, the study only showed an association and examined only a specific cohort.

Tests for Latent Infection

Two types of tests are available for TB infection in the United States: the TB skin test and the TB blood test. Your health care provider will choose one based on the reason for testing, test availability, and cost. Typically, it is not recommended to administer both tests.

Tests for Active Disease

The doctor first inquires about the patient’s TB history, demographic factors, and underlying medical conditions such as HIV or diabetes that may elevate the risk of latent TB progressing to disease. Then, a physical examination is performed to obtain information about the patient’s overall health. TST and TB blood tests may also be used. Other commonly used tests may include the following:

- Chest radiograph (X-ray): A posterior-anterior chest radiograph identifies lung abnormalities that may suggest TB, but it cannot definitively diagnose TB. However, it’s still helpful in ruling out pulmonary TB in individuals with a positive TST or TB blood test and no symptoms.

- Sputum smear microscopy: Ideally, two or three sputum (phlegm) samples are collected on consecutive mornings. Detecting acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on a sputum smear suggests TB disease, but it doesn’t confirm the diagnosis, as not all AFB are necessarily Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Mycobacterial culture: To perform this test, a body fluid or tissue sample, typically from the lungs, bone marrow, or liver, is required. Most often, a sputum sample will also be taken. The sample is cultured in a special dish and observed for up to six weeks to detect bacterial growth. If there is no disease, bacterial growth will not occur in the culture medium. A positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis confirms TB disease.

- Drug resistance (drug-susceptibility) testing: While the United States has controlled multidrug-resistant TB (having resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampin) and rifampin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) through effective public health measures, global cases caused by these resistant strains have been on the rise until recently. Therefore, initial Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolate should be tested for drug resistance to identify it early for effective treatment.

- Permanent lung damage.

- Extensive lung destruction, necrosis, and gangrene: Pulmonary gangrene is a rare complication of severe lung infection, leading to the detachment of one segment or lobe of the lungs. If left untreated, lung gangrene can cause sepsis, multiple organ failure, and death.

- Pneumothorax: Pneumothorax is a collapsed lung resulting from the accumulation of air escaping to the space between the membranes surrounding the lungs. This results from the weakening of the lung tissue, allowing an air leak.

- Hemoptysis: Hemoptysis is the coughing up of blood from the lungs, and it’s a result of bleeding from bronchial, pulmonary, and intercostal arteries.

- Bronchiectasis: Bronchiectasis is a lung disease marked by chronic widening bronchial airways and weakened or absent ciliary fibers that normally transport old mucus from the lungs. It can result from lymph node inflammation-induced compression on the bronchial tree.

- Increased risk of developing lung cancer.

- Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is a persistent fungal lung infection commonly associated with Aspergillus fumigatus, but not exclusively.

- Septic shock: Septic shock is a critical medical condition that occurs when the blood pressure dramatically decreases to a dangerously low level following an infection that has moved into the blood.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): ARDS is a severe lung injury causing fluid leakage into the lungs, leading to difficulty breathing and inadequate oxygen intake.

- Empyema: Empyema refers to the accumulation of pus in the space between the inner chest wall and the lungs.

- Systemic amyloidosis: Systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition where misfolded proteins build up in tissues, causing organ dysfunction and potential harm.

- Bronchopleural fistula: Bronchopleural fistula is an abnormal link between the bronchial tree and the pleural space. It has a high mortality and can be a complication of pleural TB.

- Fibrothorax: Fibrothorax represents the most severe type of pleural fibrosis, the thickening of the pleura, restricting lung movement. Fibrothorax is another complication of pleural TB that has eroded the lung tissue.

- Severe spinal deformity: This is a complication of spinal TB.

- Neurologic deficit: A neurologic deficit indicates an abnormal functioning of a specific area of the body and is a complication of spinal TB. Sometimes, paraplegia may occur, which paralyzes the lower half of the body.

- Hydrocephalus: Hydrocephalus is a neurological condition resulting from an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid within the brain’s deep cavities. It’s a complication of TB meningitis.

- Intestinal obstruction: This is a complication of intestinal TB.

Latent Infection

As per 2020 latent TB treatment guidelines, the regimens are recommended only for individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis presumed to be susceptible to isoniazid or rifampin. Their goal is to ensure an infected individual won’t develop active TB in the future. The different regimens include the following:

- Three months of once-weekly isoniazid plus rifapentine: This is preferred, particularly for children over 2 and adults.

- Four months of daily rifampin: This is for HIV-negative individuals of all ages.

- Three months of daily isoniazid plus rifampin: This is conditionally recommended for adults and children, including those with HIV.

- Two regimens of six and nine months of daily isoniazid: These are alternative recommendations.

Active Disease

To treat TB disease, combination therapy is always necessary, and the use of monotherapy should be avoided. The following are treatments for active TB:

- First-line: These are primary drugs recommended for the standard treatment of TB, including isoniazid, rifampicin, rifabutin, rifapentine, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.

- Second-line: These are alternative drugs used when first-line medications are ineffective, poorly tolerated, or in cases of drug resistance. They include injectable aminoglycosides, injectable polypeptides, fluoroquinolones, para-aminosalicylic acid, cycloserine, terizidone, ethionamide, prothionamide, thioacetazone, and linezolid.

- Third-line: These are drugs with uncertain efficacy against TB, reserved as last-resort options for total drug-resistant TB. They include clofazimine, linezolid, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, imipenem/cilastatin, and clarithromycin.

- Medicines for multidrug-resistant TB: High doses of first-line and second-line medications are combined to treat MDR-TB. One drug specifically for treating MDR-TB is the FDA-approved bedaquiline.

- Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids are occasionally used in TB treatment for patients with significant inflammation, particularly in cases of ARDS or TB meningitis and pericarditis.

- Better treatment results: In a guide prepared by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the links between mental health and TB are thoroughly outlined. In one of the systematic reviews mentioned, depression was associated with worse treatment outcomes. Although depression isn’t always a mindset, having a positive mindset is often linked to lower rates of depression.

- Better TB infection prevention: One systematic review found that people with mental health conditions, such as depression and schizophrenia, have a higher incidence of TB infection, making them a high-risk group that should be targeted for screening and treatment.

- Better adherence to treatment regimens: A significant challenge in TB treatment is patient nonadherence to the regimen due to a prolonged course of antibiotics. This leads to extended disease transmission and drug resistance development. A positive mindset can improve adherence to the prescribed TB treatment regimen, achieving better results.

- Stress reduction: Managing stress is crucial during the TB recovery process. A positive mindset may help individuals cope with stress more effectively, as chronic stress can negatively impact the immune system.

1. Medicinal Herbs

Medicinal herbs are commonly found in standardized extract forms, such as pills, capsules, lozenges, tablets, liquid extracts, and teas. The following have some anti-TB properties:

- Indian gooseberry (Phyllanthus emblica): Indian gooseberry is widely acknowledged as a key medicinal plant in the traditional Indian Ayurveda medicine system, with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, chemopreventive, and neuroprotective properties. The herb and its extracts and supplements are rich in vitamin C, phenols, dietary fiber, and antioxidants. Indian gooseberry is usually administered by using a compound called Jawarish amla. As per one study, after some participants took Jawarish amla daily for 60 days along with standard TB medications, many of their TB symptoms and drug side effects greatly subsided, and test parameters significantly improved. The researchers concluded that Jawarish amla had been proven a safe and effective adjuvant in managing the side effects of anti-tubercular drugs.

- Garlic (Allium sativum): In various traditional medicinal practices, garlic has been used as an established remedy for TB, as it contains allicin, ajoene, and various sulfur compounds, with antimicrobial, anti-cancer, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and cardiovascular properties. In one study using laboratory cell cultures, an allicin-rich garlic extract was found to be more effective against mycobacteria than standard anti-TB drugs isoniazid and ethambutol, while another ajoene-rich extract had a comparable activity level to these drugs. In an animal study, researchers discovered that allicin showed potent anti-TB effects against drug-sensitive, multidrug-resistant, and extensively drug-resistant strains of TB, concluding allicin could become an adjunct to classical antibiotics used in TB treatment.

- Astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus): Astragalus, a traditional Chinese medicinal herb, has been used to bolster the immune system, prevent respiratory infections, lower blood pressure, address diabetes, and protect the liver due to its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. The herb’s two major natural active components are Astragalus polysaccharide, extracted from Astragalus stems or dried roots and is the herb’s most important natural active component, and Astragaloside, another important bioactive constituent with pharmacological properties. One animal study found both components capable of enhancing the ability of macrophages to ingest TB bacteria while encouraging their release of certain proteins involved in immune responses.

- Dzherelo (Immunoxel): Dzherelo is an approved oral botanical compound that modulates the immune system, enhancing the body’s ability to combat infectious diseases, including TB. A systematic review found that using this compound as an additional treatment for pulmonary TB may improve the effectiveness of anti-TB therapy. However, conclusive evidence regarding its efficacy requires better-designed clinical trials.

- NiuBeiXiaoHe (NBXH): NiuBeiXiaoHe, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine prescription, is comprised of Bulbus fritillariae cirrhosae, Bletillae tubers, Platycodon grandiflorum root, Fructus arctii, Houttuyniae herba, and glutinous rice, and has demonstrated effectiveness against TB in an animal study.

Diet tips that can help reduce TB risks and symptoms include eliminating suspected food allergens (e.g., milk and gluten), incorporating B vitamins and iron-rich foods (e.g., dark leafy vegetables), consuming antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables, avoiding refined and trans fat foods, choosing healthy oils (e.g., olive oil), and reducing stimulants (e.g., alcohol and tobacco). The following supplements may also be helpful:

- Vitamin D: Vitamin D, which regulates macrophage function, can boost human anti-mycobacterial activity, and vitamin D deficiency is associated with an increased risk of TB infection. One study showed that toll-like receptors triggered direct antimicrobial activity to destroy intracellular TB bacteria. Another study found that vitamin D might aid in accelerating treatment for individuals with multidrug-resistant pulmonary TB.

- Bergenin: Found in many medicinal plants, the chemical bergenin shows diverse pharmacological activities, including anti-HIV, antifungal, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. Bergenin can potentially be a valuable adjunct to TB treatment, as it induces protective immune responses and inhibits mycobacterial growth. As per one animal study, combined treatment with bergenin and anti-tubercular treatment reduced immune impairment, shortened treatment duration, and significantly decreased bacterial loads of an MDR-TB strain.

- Curcumin: Curcumin is a polyphenol produced from turmeric, with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. One animal study found that curcumin exhibited bactericidal effects, effectively managing pulmonary mycobacterial infection and reducing neuroinflammation caused by the TB infection. The study authors believe curcumin holds promising potential as an adjuvant therapy in TB treatment.

3. Mind-Body Practices

In one study, the participants were randomly assigned to one yoga and one breathing group. After two months, the yoga group demonstrated a higher rate of sputum conversion and negative sputum culture and a greater reduction in symptoms compared to the other group, suggesting the potential benefits of yoga in TB management. The researchers concluded that yoga could play a complementary role in treating TB.

- Avoid high-risk and poorly ventilated environments: Limit exposure to individuals with active TB, especially in closed, crowded, and/or poorly ventilated environments. Minimize trips to regions with high TB infection rates. Before taking a trip, visit a travel clinic for advice. Fortunately, air travel generally poses a relatively low risk of contracting TB infection.

- Test for potential TB infection: Skin/blood testing for TB is used in high-risk populations or individuals with potential exposure, such as health care workers. Those exposed to TB should promptly undergo an initial skin/blood test and follow up with another test if the initial one is negative.

- Prevent latent TB infection from progressing to active disease: If a person has latent TB infection, he or she should take medications at a doctor’s recommendation to kill the bacteria, thus preventing the latent infection from developing into active TB disease.

- Ensure your home or workplace has adequate ventilation.

- Support your immune system: Exercise regularly, eat healthily by avoiding processed and inflammatory foods, get seven or eight hours of sleep each night, and manage stress levels.