We rarely think about sweat as anything more than a side effect of heat or exercise, but it may be more valuable than we realize. The drops our bodies naturally excrete contain a chemical fingerprint of what’s happening inside, including early warning signs of diseases such as diabetes, cancer, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s that a doctor might not catch for years.

Sweat contains biomarkers, such as cortisol, hormone levels, electrolytes, glucose, and even medication levels that offer clues about everything from stress and metabolic health to how well a person is responding to treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis.

However, unlocking sweat’s full diagnostic potential isn’t simple. Results can vary widely from person to person, and technical hurdles remain before devices can be trusted in clinical settings alongside traditional screenings such as blood and urine tests.

How Sweat Monitors Work

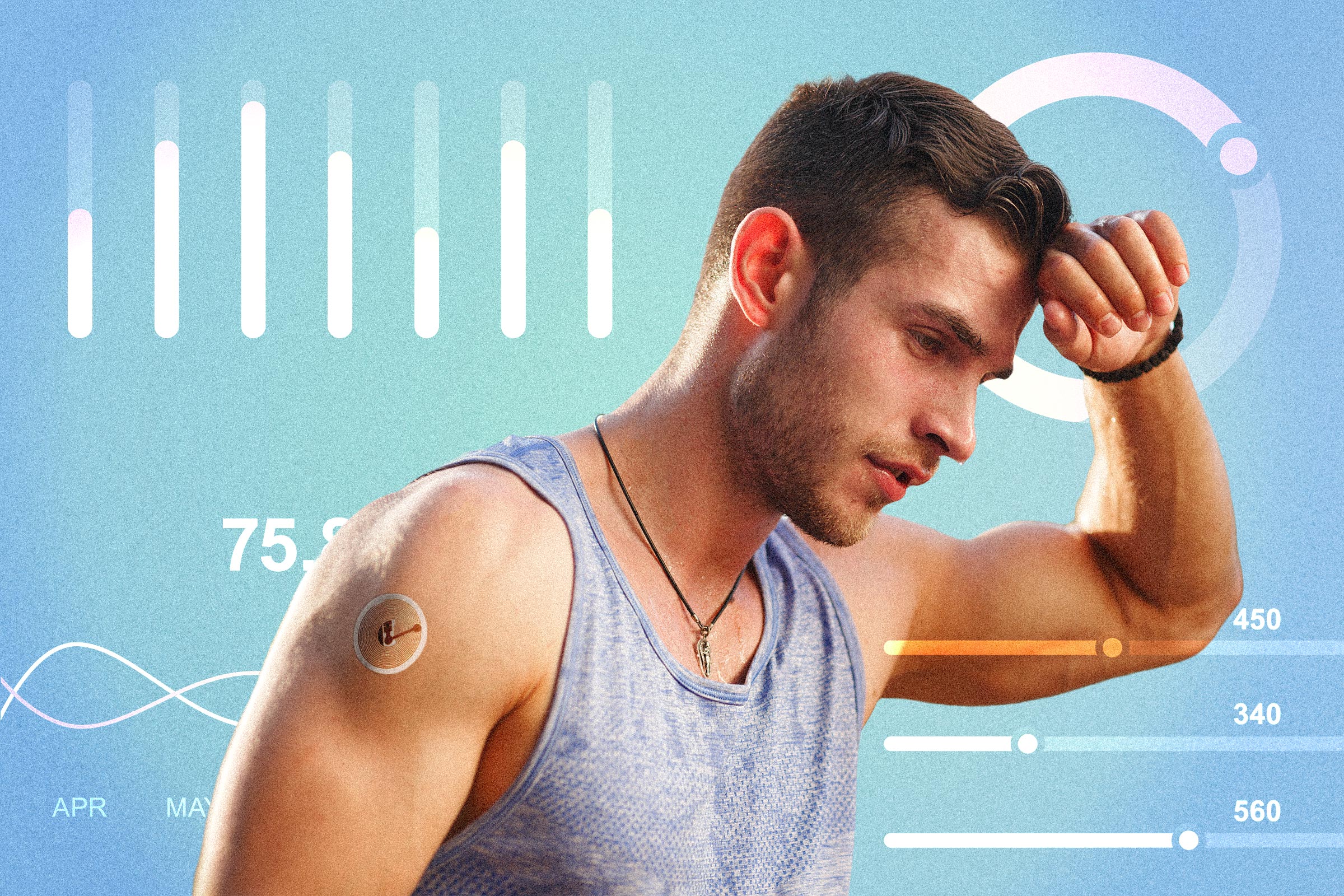

Four main types of sweat-collection devices are currently commercially available, most of which use wearable patches or absorbent pads placed directly on the skin. The patches can stay attached for up to 14 days, allowing people to shower, exercise, and go about their daily routines.

Once sweat is produced, it flows through tiny channels or soaks into materials inside the device, John Rogers, a researcher on a 2023 study published in Science on sweat as a diagnostic biofluid and a faculty member in Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University, told The Epoch Times. “These channels, each the diameter of a human hair, captures, stores, and analyzes biomarkers in sweat using color changing chemistries.”

In most cases, enough sweat can be collected in about 30 minutes.

Some patches, such as the Gx (Gatorade) sweat patch, can deliver real-time information through a mobile app, measuring hydration and electrolyte levels in athletes during exercise.

These systems don’t just measure chemicals in sweat, but try to interpret what those measurements actually mean for a person’s body using AI and machine learning, Roozbeh Ghaffari, CEO and co-founder of Epicore Biosystems, and another author of the Science study, told The Epoch Times. “AI and machine-learning models play a key role downstream in data analysis by breaking down personalized interpretations of large datasets based on factors like sweat rate, temperature, activity level, and baseline health.”

From Athletic Performance to Disease Screening

Sweat analysis has long been associated with athletic performance, where it is used to monitor hydration status, electrolyte loss, and thermoregulation during training and competition. For athletes, these measurements help optimize performance, prevent fatigue and cramping, and reduce the risk of injuries by enabling personalized hydration and recovery strategies.

While current commercial applications focus mainly on hydration and electrolyte tracking for athletes, researchers are exploring sweat’s potential for early disease detection.

Sweat removes waste products from the body, including excess micronutrients and toxic substances. Because many of these chemicals also circulate in the bloodstream, sweat can reflect what is happening inside the body, without the need for more invasive tests.

One example is measuring glucose, a sugar that provides energy to cells and is routinely monitored during health assessments, especially for people with diabetes. Although sweat-based glucose monitoring is still being refined, it shows promise as a less painful alternative to frequent finger-prick tests.

Sweat also contains biomarkers associated with inflammation, the body’s natural response to injury or infection. These include cytokines, which signal immune activation, and lactate, which increases when tissues are stressed.

Chronic inflammation is linked to autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Studies have found that early detection of diseases can lead to better treatment outcomes, as doctors can often begin treatment sooner and prevent the condition from becoming more serious. Early detection can also reduce the need for aggressive treatments and improve a patient’s overall quality of life.

Neurological Diseases Leave Traces in Sweat

Recent research suggests sweat analysis could help detect Alzheimer’s disease.

While Alzheimer’s primarily affects the brain and memory, it can also impact sodium levels. Sodium in sweat is important because it helps regulate body temperature, and changes in sweat sodium levels may make people with Alzheimer’s more sensitive to heat, increasing their risk of heat-related problems.

A 1993 study found that about 27 percent of women with Alzheimer’s showed reduced sweating, compared to only 7 percent of the healthy control group. Reduced ability to sweat could make it harder for people with Alzheimer’s to cool down, increasing their risk of heat stress.

Sweat may also help detect Parkinson’s disease, a neurological disorder caused by the gradual loss of cells that produce dopamine, a chemical needed for movement and coordination. Since diagnosing Parkinson’s early can be difficult, researchers are looking for new biological markers that could help detect the disease sooner and monitor how it progresses.

One study analyzed skin swabs from 150 people and found clear differences in sebum—an oily substance produced by the skin—between people with Parkinson’s and those without it. However, more research is needed to confirm whether these differences can be reliably used to diagnose the condition.

Sweat analysis is not limited to health-related markers—it can also reveal exposure to drugs such as amphetamines, opioids, and cocaine, as well as pesticides. Detection can help with medical monitoring, workplace safety, and environmental exposure studies. For instance, it could help identify ongoing exposure to harmful chemicals in agricultural or industrial settings, allowing safety measures to be improved. More specifically, it can detect exposure to heavy metals and toxins, such as lead, arsenic, and mercury, enabling early intervention before serious health effects develop.

Sweat Monitoring vs. Blood Testing

Monitoring sweat has many advantages—offering a larger detection window and the detection of biomarkers at a deeper molecular level, according to the study published in Science.

“Sweat monitoring is much more convenient than blood because access to sweat does not require penetration of the skin,” Rogers said. “The tests can be run at home without the need for specialized facilities or trained personnel.”

Sweat testing could make health monitoring more accessible, especially for people who need frequent testing, such as athletes, people with chronic conditions, or people who want to track overall wellness.

However, scientists don’t see sweat as a replacement for blood testing entirely. “We view sweat as a new physiological data stream that complements existing tools, particularly for monitoring and personalized wellness and health interventions,” Ghaffari said.

In other words, sweat adds another layer of information, giving doctors and researchers a more complete picture of what’s happening inside the body.

The dynamic nature of sweat presents some challenges. “Until recently, there were major barriers, including difficulty collecting clean, time-resolved sweat samples, a limited understanding of how sweat biomarkers correlate with blood/serum levels, and a lack of wearable platforms that can measure data,” Ghaffari said.

Other problems include evaporation of sweat from the skin, contamination of sweat with other substances, and handling sweat in small volumes. Getting enough sweat is a typical problem, especially in infants and young children.

The Future of Sweat Testing

“At the moment, the most realistic and impactful early-detection applications are in monitoring and screening,” Ghaffari said.

Near-term applications include detecting fluid loss and electrolyte imbalance before dehydration symptoms emerge, managing physiological stress and fatigue in athletes, monitoring chronic conditions, and tracking environmental and occupational exposure.

Looking ahead, combining sweat analysis with wearable technology, AI, and mobile apps could make personalized health tracking even more precise and convenient. Continuous sweat monitoring could alert people in real time about hydration levels, stress, and toxin exposure, enabling proactive health protection.

“As large-scale datasets and clinical validation studies advance, we should expect a broader range of sweat-based screening, monitoring, and management capabilities to become commercially deployed over the next two to five years,” Ghaffari said.