Stephen Grady’s world turned upside down one day.

He woke up at 5 a.m. with what he thought was a cramp. It turned out to be a stroke.

Grady was taken to the hospital, paralyzed down his entire right side.

“I was in shock because I was so fit, and I kept thinking, ‘Why me?’” Grady told The Epoch Times.

“I didn’t want this life. I just wanted to be normal again. I wanted the old me back—playing football, golf, going to the gym with my wife, rushing around at 100 miles an hour, working, going on holidays together.”

A clinical trial using vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) gave him hope. The transcutaneous limb recovery post-stroke (TRICEPS) trial, underway at King’s College Hospital in the UK, is a rigorous, multi-center study investigating whether a noninvasive technique, transcutaneous (through-the-skin) VNS, can improve hand and arm function in stroke survivors when paired with rehabilitation therapy.

“I might get my arm and hand back to use functionally—so it’s not just hanging there,” Grady said.

Rethinking Stroke Recovery

Arshad Majid, a consultant neurologist and chief investigator of the TRICEPS trial, had used VNS for years to treat epilepsy.

It later came to his attention that cardiologists were using VNS as part of active rehabilitation to help patients recover after heart attacks. Stroke recovery, in contrast, hadn’t taken the same proactive approach. Seeing how it was helping in cardiology sparked a new idea in Majid—maybe VNS could also support the brain’s recovery after a stroke by boosting its ability to rewire and heal.

The need for better solutions is clear. Many people who survive an ischemic stroke live with long-term disabilities, particularly in the arm, shoulder, hand, or wrist, referred to as upper extremity impairments. More than 60 percent of survivors face lasting challenges with movement, which affect daily activities and overall independence. Even five years post-stroke, about one in five report a very poor quality of life.

While intensive physical and occupational therapy can lead to improvements, sometimes even years after a stroke, most people hit a recovery plateau early. Progress tends to slow significantly after the first few months, and few treatments have delivered consistent, long-term benefits.

“If our new TRICEPS trial is successful, it will be the first large-scale, properly controlled evidence that vagus nerve stimulation makes a real difference in stroke recovery,” Majid told The Epoch Times.

Encouraging Results

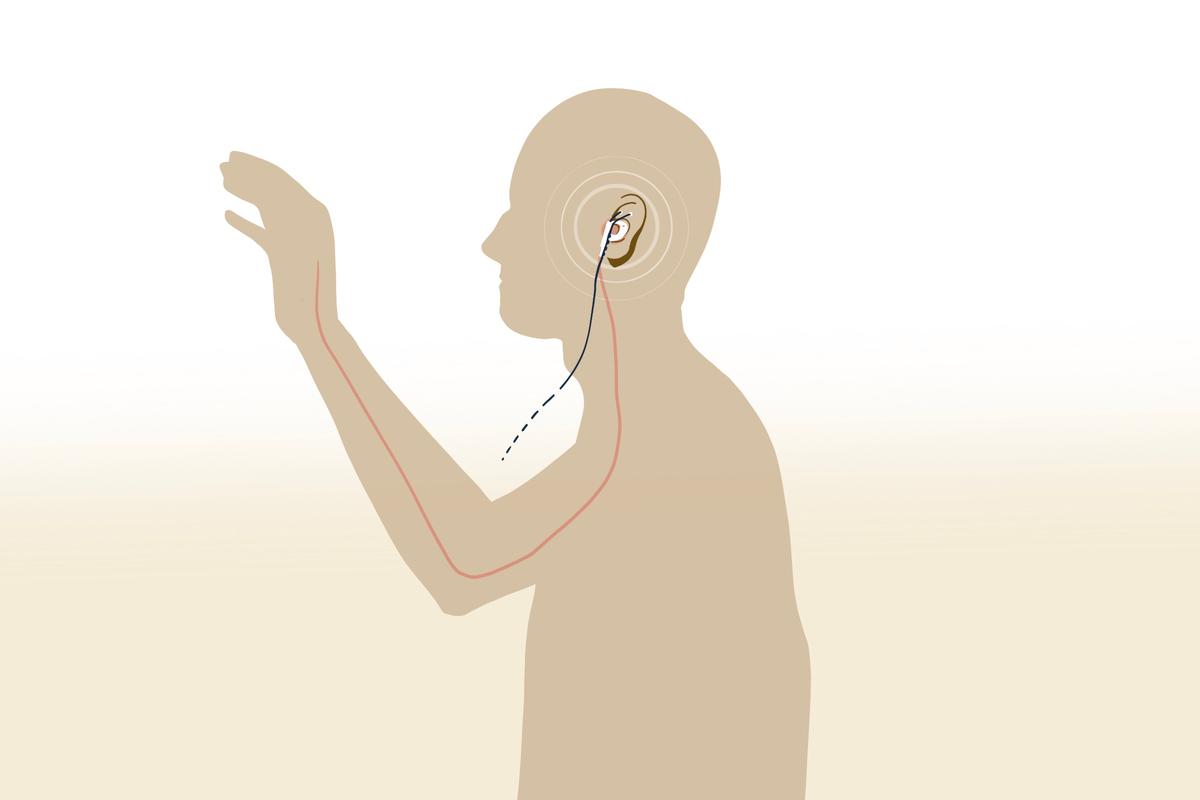

Traditionally, VNS involves surgically implanting a device in the neck, much like a pacemaker. But for stroke patients, many of whom are on blood thinners and at increased surgical risk, this isn’t ideal. Majid’s team turned to a less invasive option: transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS), delivered via the ear.

The tVNS device and how it may help restore arm function after a stroke. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

The team began with a small pilot study, involving a dozen participants, that paired tVNS with physical movement. After six weeks, the team observed improvements in patients’ arm weakness.

“There was a signal there,” Majid said. “We didn’t have a control group, but it gave us reason to be optimistic.

“One participant, a boxing coach, couldn’t use his arm at the start of the study. Six weeks later, he was punching a bag again.”

In the early study, participants also saw meaningful improvements. Some went from not being able to change a baby’s diaper to doing so independently or from struggling to turn a key in a lock to confidently driving and carrying a cup of coffee, according to Majid.

Encouraged by these outcomes, the team launched the large-scale TRICEPS trial. An interim analysis phase, conducted as a safeguard to assess whether the treatment was showing enough promise to continue, has shown positive results. The final results are expected in early 2027.

A unique aspect of the TRICEPS trial is that participants receive the treatment at home. Participants self-administer tVNS for one hour per day, over three months—an accessible alternative to previous in-hospital or surgical approaches.

The cost difference is also significant: While invasive VNS devices can cost anywhere from $39,000 to $45,500, including surgical and hospital expenses, the tVNS device costs about $1,300 and poses no surgical risks.

What the team hopes to see is a clinically meaningful improvement, defined as a five- to six-point increase on a recognized stroke recovery scale. Numbers aside, the team is also conducting a qualitative component to ask patients what those changes actually mean in daily life.

“We want to understand how this affects real-world function—what can you do now that you couldn’t before?” Majid said.

According to him, if successful, the trial could reshape stroke rehabilitation and open the floodgates for more research into VNS.

The Mechanism

How exactly does VNS support stroke recovery? While the mechanisms aren’t fully understood yet, several promising hypotheses are emerging.

A stroke occurs when blood flow to part of the brain is cut off, either by a blockage (ischemic stroke) or bleeding (hemorrhagic stroke). Blocked blood flow deprives brain cells of oxygen and nutrients, triggering inflammation and cell death. Depending on the location, the result may be muscle weakness, paralysis, loss of coordination, and difficulties with speech, memory, vision, understanding, or emotions.

Although the brain begins repairing itself in the days and weeks following a stroke, recovery can be impeded by ongoing inflammation, disrupted neural circuits, and stress-related responses, especially if rehabilitation is delayed.

“This is where VNS becomes particularly valuable,” Priyal Modi, an integrative medical doctor, told The Epoch Times.

The vagus nerve carries information bi-directionally from the brain to many key organs in the body. It also supports neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire and form new connections, according to Modi.

“When paired with rehabilitation exercises, VNS enhances the brain’s learning capacity by increasing neurotransmitters like acetylcholine and norepinephrine, helping the brain remember successful movements and regain motor function more effectively,” she said.

VNS appears to promote the growth of both new brain cells and blood vessels, improving circulation in areas damaged by stroke. Improved circulation could aid recovery by enhancing the delivery of nutrients and oxygen where they’re most needed. VNS may also help stabilize the blood-brain barrier, which often becomes leaky after a stroke.

VNS helps tone down the immune response, which can become overactive after a stroke, according to Modi.

Another often overlooked factor in stroke rehabilitation is sleep. Insomnia affects up to 59 percent of stroke survivors and has been linked to slower recovery and increased risk of further complications. VNS has shown promise in treating both primary insomnia and insomnia associated with depression, two common concerns after stroke.

Perhaps most compelling is the longevity of the results. When VNS is paired with physical therapy, the improvements in upper limb function and overall quality of life can last well beyond the treatment window. Gains have been observed for up to a year (and in some cases, for two to three years) after therapy ends, suggesting that VNS may not only accelerate recovery, but also extend it.

Stimulate Naturally

Besides VNS devices, there is growing interest in natural ways to stimulate the vagus nerve as part of a more holistic approach to stroke.

Breathwork techniques, particularly slow, diaphragmatic breathing, can help stimulate the vagus nerve through the lungs and diaphragm. Breathwork helps shift the nervous system into a more calm, restorative state, supporting the body’s innate intelligence and healing capacity, according to Modi.

Cold exposure, including cold showers or plunges, gentle humming or chanting, and mindful movement, such as yoga or tai chi, are other natural ways to activate the vagus nerve, she noted.

While these methods are not a direct substitute for medical-grade VNS, they are particularly useful.

“I’ve seen firsthand how natural and noninvasive VNS techniques can support stroke survivors,” Modi said.

Jodi Duval, a naturopathic physician, has also helped stroke patients by using VNS techniques, which naturally activate vagal motor fibers. She also uses ear acupuncture, focusing on parts of the ear connected to the vagus nerve, and often recommends a device called Sensate, which uses gentle infrasonic vibration over the chest to stimulate vagal tone.

“One client recovering from a left-sided stroke integrated structured diaphragmatic breathing, auricular [ear] acupuncture, and Sensate into their rehab plan,” Duval said.

Over time, the patient reported more stable energy, improved sleep quality, and greater emotional resilience, which helped this client engage more fully in physical rehabilitation.

Duval said she believes that natural VNS remains a largely untapped resource in stroke care.

“These interventions are especially valuable in early recovery or in settings where surgical or invasive methods are inaccessible,” Duval said.

Support Caregivers

Stroke’s impact extends beyond patients—it places a heavy physical and emotional burden on caregivers.

Tasks such as helping with mobility, communication, and daily routines can be overwhelming, especially when progress is slow or uncertain. A 2022 study of caregivers to first-time stroke survivors found that caregiver stress was strongly linked to the patient’s level of disability.

Effective VNS treatment, when it helps restore even modest function, can ease the burden. Greater independence in daily tasks means fewer hours spent assisting with basic needs, reduced emotional strain, and more space for caregivers to tend to their own health, work, and personal lives. For many, even small gains in movement or communication can feel transformative.

“For stroke survivors and their families, this offers hope, even years after the initial event,” Modi said.

A Hope

VNS isn’t a cure, but it’s a powerful support, especially when paired with targeted rehabilitation, Modi said.

It reflects a broader shift in stroke care: moving beyond symptom management to enhancing the brain’s ability to adapt and heal.

“The nervous system is incredibly adaptable, and with the right stimulation and support, recovery is often more possible than we once believed,” Modi said.

Grady has already noticed small gains and said his arm doesn’t feel like it’s just hanging there anymore.

“Regaining full function would mean the world to me,“ he said. ”To use my arm and hand in everyday tasks again—just that.

“I have a different outlook on life now. I appreciate the simple things more. Life is hard at the moment, but I will never give up.”

Update: The article has been updated to include the interim results of the TRICEPS trial.