Losing touch with old friends is a universal experience. A birthday, a visit to a childhood home, or meeting someone new who looks familiar can evoke memories of past connections. These moments often lead to questions: Should I reach out? Will it be awkward? Do they remember me, too?

Studies suggest that the hesitation to reach out is often misplaced, as most people welcome reconnection more than we might expect.

Research shows that rekindling an old connection is more than a sentimental gesture—it is a way to cultivate deeper meaning and increase one’s sense of belonging, identity, and well-being. However, despite these well-documented benefits, people are often as reluctant to reach out to their old friends as they are to talk to a stranger.

Friendships Keep Us Healthy

Love is baked into the very definition of friendship, as the word “friend” originally traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root priy, meaning “to love” or “beloved” (as in the Sanskrit priya, meaning “dear”).

Cicero’s treatise “De Amicitia” (“On Friendship”) states that true friendship only exists between good people, is based on virtue and character, continues beyond death, augments joy, and helps bear grief. “Friendship is nothing else than an accord in all things, human and divine, conjoined with mutual goodwill and affection,” wrote Cicero.

He saw friendship as essential to his philosophies of happiness and human flourishing.

Indeed, research over the past decades positively links friendship to mental and physical health, quantifying the insights of philosophers and spiritual teachers. Meaningful social relationships are a robust source of well-being and happiness.

According to a meta-analysis of nearly 309,000 people, those with strong social relationships were 1.5 times more likely to survive than those with weaker or insufficient social relationships. In other words, quality of relationships predicts mortality just as much as alcohol consumption and smoking and surpasses the influence of risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity.

Early friendships matter, too. A longitudinal study of 1,103 French young adults found that those who had no close childhood friends were more than two times as likely to experience high levels of depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic complaints, such as chronic pain, headaches, and fatigue.

Why Do We Hesitate to Reconnect?

Despite the well-documented and wide-ranging benefits of social connection, people are hesitant to reach out to old friends. This is surprising, akin to the wisdom that it’s easier to keep tea warm than to reboil it—rekindling an old friendship usually requires less effort than the estimated 200 hours it takes to develop a new close friend.

In 2024, researchers Lara Aknin and Gillian Sandstrom conducted seven studies published in Nature Communications Psychology. Their findings showed that more than 90 percent of people had lost touch with a friend they once cared about. Despite this, when participants had the opportunity to write a note and reconnect with their friend, fewer than one-third took the step of sending the note. This was the case even though efforts were made to assure them that their messages would be well received.

This series of studies was inspired by personal experience. Aknin, a distinguished professor at Simon Fraser University with a doctorate in psychology, recounted to The Epoch Times how she had fallen out of touch with Sandstrom, whom she had known in graduate school and as a collaborator on research projects.

Despite missing her, Aknin felt reluctant to reach out and waited until the new year for an excuse to send her a message. Sandstrom immediately responded to her, and the two decided to work on a project together, inspired by Aknin’s experience of hesitation.

In the joint experiment, participants cited concerns about potential awkwardness and fear that their friend might not want to hear from them despite wanting to rekindle the connection. Thus, the reluctance to reconnect was specifically about being the one to initiate contact, not the act of reconnection itself. In one of the studies, participants reported that they were no more inclined to reach out to an old friend than to chat with a stranger or pick up litter.

Aknin, director of the Helping and Happiness Lab, described the hesitation to reach out as a “very unfortunate forecasting error that keeps forcing us to … keep to ourselves when, in fact, it makes us so much happier and so much more connected when we reach out.”

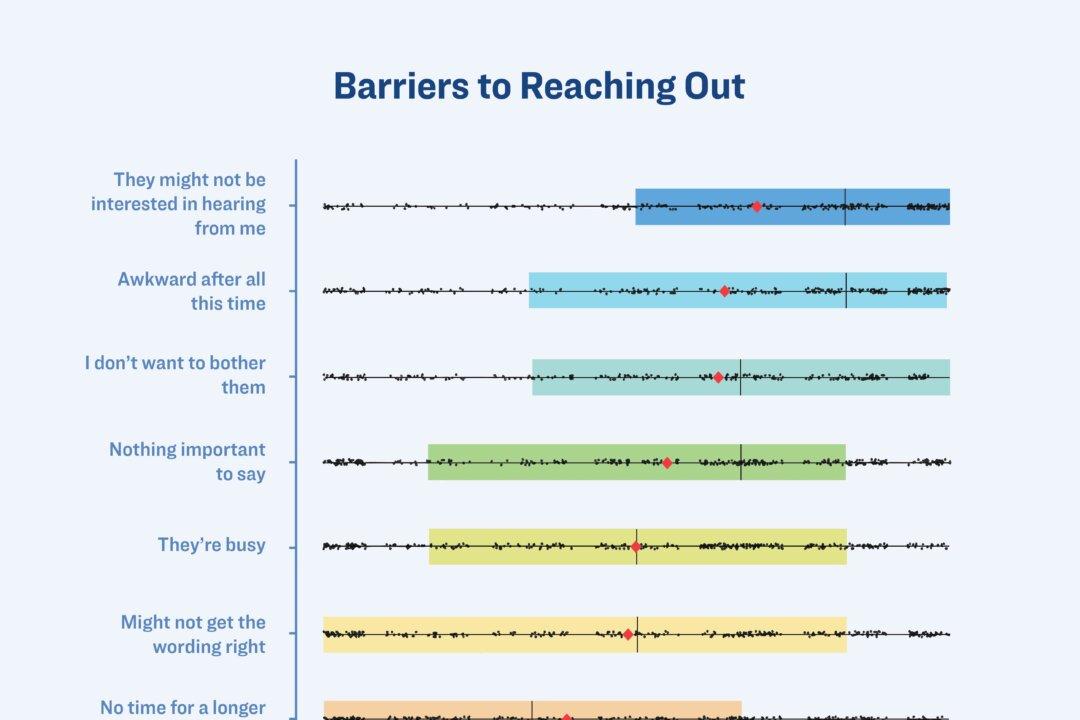

People reported several reasons for hesitating to reach out to an old friend, despite caring about the relationship. The most common concern is that their friend might not want to hear from them, followed by the worry that contacting them would be awkward. (Illustration by The Epoch Times.)

Research demonstrates that people overestimate the discomfort of getting in touch with an old friend while underestimating the positive effects and appreciation such acts encourage and elicit.

These misjudgments in social cognition are not only limited to the time before an interaction takes place but extend to post-conversation evaluations. Researchers at Cornell, Harvard, and Yale found that following a conversation, people systematically underestimated how much their conversation partners liked them and enjoyed their company, calling this illusion the “liking gap.”

Rekindling Friendships

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were strict stay-at-home orders in most regions of the United States, many people took to their phones to rekindle old friendships. Their motives for reconnecting ranged from simply checking in after a period of losing contact to wanting to reminisce about a positive memory together. Researchers called this phenomenon the “Great Reconnection” and found that those who confided a breadth and depth of personal and intimate thoughts while reconnecting reported lower levels of depression and loneliness.

To encourage reaching out, in their experiment, Aknin and Sandstrom divided participants into two groups. Those in the practice condition were asked to send messages to current friends and acquaintances for three minutes (on average, each person reached out to three contacts), while those in the control condition were told to browse social media feeds for the same amount of time (on average, they looked at six or seven accounts). All participants were then encouraged to send a note to their old friend and were assured that this act of kindness would benefit both themselves and their friend by increasing their happiness.

Fifty-three percent of participants in the practice condition got in touch with their old friend, while 31 percent of participants in the control condition did so.

“I would recommend that [people] take the behavioral intervention to heart. Just warm up by sending a couple of messages to the folks at the top of their most recent contacts, people they’re frequently in touch with, and then just take that leap. Don’t overthink it, and just do it,” Aknin told The Epoch Times.

Pete Bombaci, founder and CEO of GenWell, a movement dedicated to fostering human connections, told The Epoch Times about a positive moment of reconnection that happened at a workshop conducted for a Chamber of Commerce:

“During this workshop, a lady reached out to her ex-husband’s sister, who, before their divorce, was her best friend. They had not spoken for I believe … 13 years. We finished the 90-minute workshop, and at the end, I asked if anyone had heard from the person that they had reached out to, and she raised her hand and said that her old friend had gotten back to her almost immediately and that they had scheduled a coffee for the following week.”

Aknin said, “People have told us that there’s both this risk and excitement of reaching out to friends from the far, far past, that in many ways for folks represents a period locked in time.”

These findings are reflected in real-life reconnection stories, including one shared by a young woman from Georgia.

Kamryn Tucker, student assistant at Veritas Academy in Savannah, recently experienced this mixture of discomfort and reward when she reached out to friends she had played volleyball with as a teenager but had been out of touch with for four years. On the day of the reunion, Tucker initially felt uncomfortable with how much she had changed, fretting over what she would wear to the gathering. In high school, she had dressed like a tomboy, but her style had since become more feminine.

Once the young women reunited, Tucker’s doubts evaporated.

“We’d all seen such deep parts of each other in that way where it’s like we’re all siblings. Even though it had been a long time, it just felt like family we hadn’t seen in a long time when we came back together,” she told The Epoch Times.

While friendships formed later in life are often shaped by social roles, childhood friendships arise from the pure delight of shared experience. They are a reminder of when connection was more spontaneous, without the burden of self-consciousness and worldly ambitions.

“Sometimes your family knows you better than everyone and also the least out of anyone. It just kind of felt like that in that moment [of reconnection]: I’m very different, and I feel uncomfortable about that, but also these people are different too, but we’re all coming together,” said Tucker.

Old friendships don’t have to fade.

Think of an old friend you haven’t spoken to in a while. What’s preventing you from reaching out? A simple note, a shared memory, or even a brief “Hi, I’ve been thinking about you,” can be all it takes to reignite a meaningful connection. So why hesitate? Send that message, make that call, and discover the power of reconnecting.