- Abdominal pain and tenderness

- Intestinal cramping

- Unintentional weight loss or cachexia (severe weight loss with muscle wasting)

- Nausea or vomiting

- Rectal bleeding

- Decreased appetite

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Pain around the anus

- Compromised growth in children or delayed puberty

- Anemia and iron deficiency

Extraintestinal manifestations, or symptoms outside the intestines, include:

- Mouth ulcers or canker sores

- Skin disorders, such as erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum

- Joint pain and swelling, including arthritis and other joint-related issues

- Eye inflammation, such as uveitis and episcleritis

- Liver and bile duct inflammation

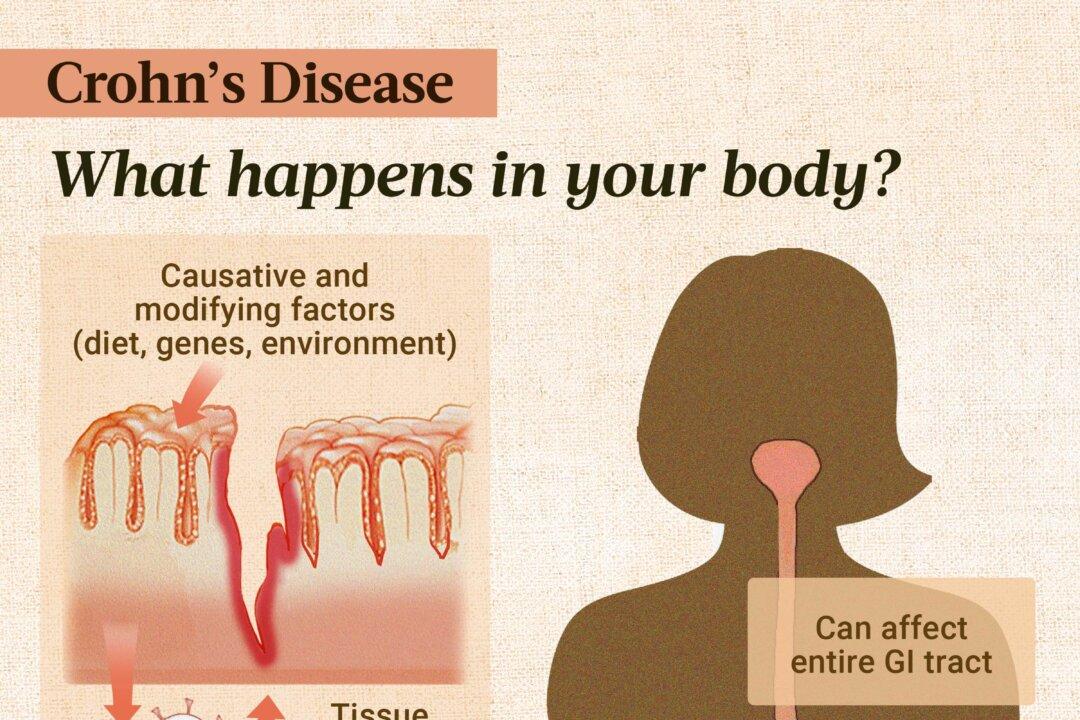

Epigenetic Factors

Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, turn genes on and off without altering DNA sequences. Epigenetic changes to gene expression—which are reversible—can influence immune responses and contribute to the onset and progression of Crohn’s disease.

Microbiome Changes

The gut microbiome, consisting of trillions of microbes, is vital for intestinal health. In Crohn’s disease, this balance is disrupted, leading to dysbiosis. Dysbiosis can manifest in different ways, including:

- Reduced bacterial diversity: A person with Crohn’s may host fewer varieties of bacterial species than healthy individuals.

- Fewer beneficial bacteria: Levels of beneficial bacteria from the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (which produces butyrate), are reduced. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) that helps strengthen the gut lining and provides energy to gut cells. Most studies show decreased Bifidobacterium in Crohn’s disease, but one study showed an unexpected increase.

- More harmful bacteria: There is an increase in potentially harmful bacteria. These include Actinobacteria, Fusobacterium, and Proteobacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), as well as proinflammatory Ruminococcus gnavus. An increase in sulfate-reducing bacteria produces hydrogen sulfide that can damage the gut lining and exacerbate inflammation.

With fewer beneficial bacteria, the production of butyrate decreases. Reduced butyrate levels weaken the intestinal lining, increasing the permeability to create a “leaky gut.” Dysbiosis can also degrade the protective mucus layer, further compromising the gut barrier.

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors like oxidative stress, dysbiosis (microbial imbalance), and chronic inflammation can trigger epigenetic changes. For example, research indicates that a diet high in total fats, saturated fats, and a higher ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids may increase disease activity, especially in those with specific genetic variations related to inflammation.

- Low dietary fiber intake disrupts the gut microbiome and impairs gut health.

- High dietary fat intake, especially from processed foods, exacerbates inflammation and increases disease risk.

- Smoking worsens Crohn’s disease in several ways, such as increasing oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to frequent flare-ups and a higher risk of multiple surgeries.

- Heavy metals can damage the intestinal lining, impact the microbiota, and induce oxidative stress and inflammation.

- Stress can increase intestinal permeability, alter the gut microbiome composition, and dysregulate the immune system.

- Eating processed meat is linked to an increased risk, likely due to its potential to cause inflammation and disrupt the microbiome.

- Increased sanitation, especially in urban environments, limits childhood exposure to infections and pathogens, potentially impairing immune system development.

- Antibiotics disrupt the balance of the gut microbiome, making individuals more susceptible to developing Crohn’s disease.

- Long-term oral contraceptive use is associated with a higher risk of Crohn’s disease, potentially due to hormonal effects on the gut lining and immune response.

- Frequent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use damages the intestinal mucosal barrier, which may contribute to the development and exacerbation of Crohn’s disease.

Dysregulated Immune System

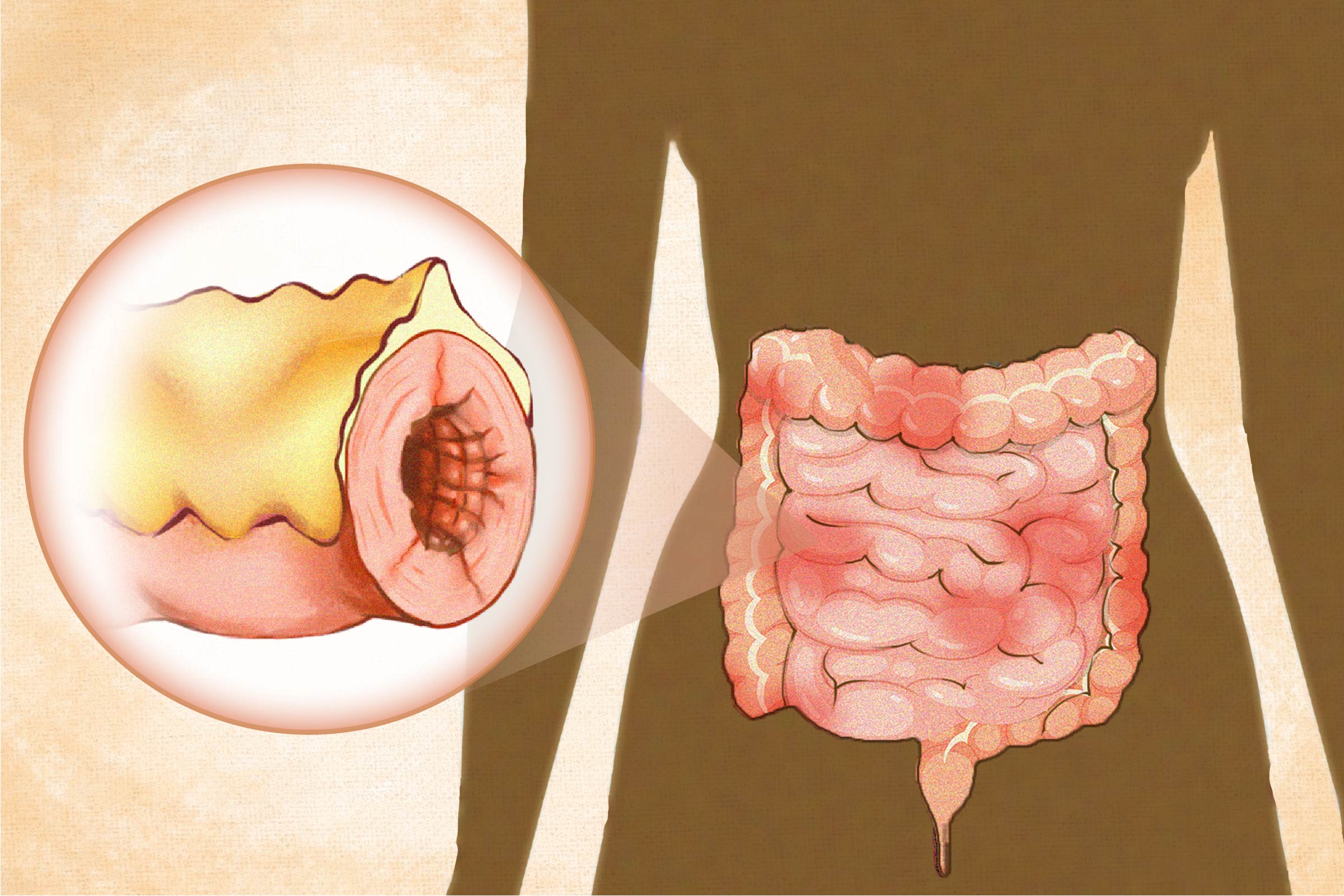

Mesenteric Fat (Creeping Fat)

Abdominal fat can be subcutaneous (under the skin) or visceral (inside the abdominal cavity). Mesenteric fat is a visceral fat surrounding the intestines (and some other organs) within the mesentery, a fold of tissue that attaches the intestines to the abdominal wall.

- Ileocolitis is the most common form, affecting both the ileum (the last section of the small intestine) and the colon (large intestine).

- Ileitis affects only the ileum.

- Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease affects the stomach and the beginning of the small intestine (the duodenum).

- Jejunoileitis affects the middle section of the small intestine (the jejunum) with patchy areas of inflammation.

- Crohn’s colitis (granulomatous colitis) is limited to the colon (large intestine). Perianal disease may accompany this type.

Classifications of Crohn’s Disease

Classification systems help guide Crohn’s disease treatment plans based on disease progression and characteristics, ensuring a more personalized approach. The classifications are as follows:

- Montreal: This widely accepted system categorizes Crohn’s disease based on age at diagnosis, location, and disease behavior (stricturing, penetrating, non-stricturing, nonpenetrating, perianal). For example, a patient classified as A2L3B2 would be diagnosed between the ages of 17 and 40 (A2), with the disease affecting both the small and large intestines (L3) and exhibiting stricturing behavior (B2).

- Vienna: An older system similar to the Montreal Classification, the Vienna Classification’s criteria differ slightly for age, location, and behavior.

- Paris: This classification is designed explicitly for children, using the same parameters as the Montreal Classification but with adjustments for pediatric concerns, such as growth. Some researchers suggest adding histology (microscopic examination of tissue) to provide more detailed insights into disease involvement.

- Age: Crohn’s disease can affect people of any age. However, the age of onset is often in the second decade of life, with a median age at diagnosis of 29.5 years.

- Sex: Crohn’s disease occurs in both sexes but slightly more frequently in females.

- Ethnicity: While Crohn’s disease can affect individuals of any ethnic background, it is most prevalent among populations of European descent. For instance, the incidence is observed to be more than twice as high in individuals of European descent than in non-Hispanic black individuals. Within the European-descent population, Ashkenazi Jews have a two to four times higher risk.

- Geographic region and latitude: North America, Europe, Greenland, and Australia have the highest prevalence of Crohn’s disease, with an increasing prevalence observed in other countries becoming more industrialized, such as Asia.

- Family history: Having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with Crohn’s disease raises one’s risk of developing the disease by up to 10-fold.

- Surgeries: Risk may be increased for up to 10 years after an appendectomy. Tonsillectomy has also been linked to higher risk in children.

- Formula-feeding: Breast milk provides beneficial bacteria, prebiotics, and immune factors that help establish a healthy gut microbiome and immune system development, helping protect the infant against Crohn’s disease.

- Cesarean birth: The lack of exposure to microbes in the vaginal canal may disrupt the seeding of an infant’s gut microbiota, increasing Crohn’s disease’s risk, particularly for boys. Notably, one study found that babies born vaginally at home and breastfed exclusively had the most beneficial gut microbiota and lowest numbers of Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) and E. coli.

- Urban living: Studies show that living in a metropolitan area increases susceptibility to Crohn’s disease, while exposure to pets and farm animals may be protective.

Other factors associated with an increased risk in children include previous admission to the hospital for a gastrointestinal infection, bedroom sharing, atopic dermatitis, and parents’ divorce.

- Blood and stool tests: Complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), fecal calprotectin, and lactoferrin are used to assess inflammation or signs of infection.

- Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy: A flexible tube with a camera is used to view the digestive tract and take tissue samples (biopsies) to confirm the diagnosis and check for any precancerous changes.

- CT scans, MRI scans, and ultrasound: These can determine the extent and location of inflammation or complications. Intestinal ultrasound is noninvasive and radiation-free, making it a good option for children.

- Enterography or enteroclysis: These are specialized tests for parts of the small intestine that are hard to reach with endoscopy. They involve drinking a contrast dye and then using X-rays, CT scans, or MRI scans to get detailed images.

Functional Medicine Testing for Root Causes

Functional medicine practitioners dive deep into a person’s health history, creating a timeline from before birth to the present. This comprehensive view helps them identify and understand the various factors that play a role in each individual’s case of Crohn’s disease. They also use specialized tests tailored to each individual to uncover the underlying causes, aiding in the creation of a personalized treatment protocol.

- Breath test for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Intestinal permeability test

- Micronutrient evaluation

- Food sensitivity and cross-reactivity testing

- Heavy metal testing

- Anemia

- Adipogenesis (fat accumulation)

- Diabetes

- Gallstones and kidney stones

- Growth issues in children

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

- Obesity

- Osteopenia or osteoporosis

- Restless legs syndrome: A 2023 retrospective cohort study of nearly 36,000 people found that people with IBD (including Crohn’s disease) were more likely to have restless legs syndrome than cohorts without IBD.

- Intestinal complications: These include narrowing (stenosis) or constriction of the intestines, tightening (strictures) that can block the intestines, and abnormal connections (fistulas) formed between the intestines and other tissues. Such complications often require surgery.

- Anxiety and depression: Crohn’s disease can significantly affect mental health, contributing to anxiety and depression. These mental health issues can further complicate the condition’s management. Furthermore, intestinal inflammation can activate the hypothalamic‒pituitary‒adrenal (HPA) axis via the brain-gut axis to induce anxiety and depression.

- Breast cancer: An activated HPA axis can inhibit anti-tumor responses in the immune system and promote breast cancer development.

- Clostridioides difficile infection: Infection with the bacterium C. diff is a serious complication of Crohn’s disease. A study of hospitalized Crohn’s disease patients found the incidence of C. diff infection to be 12.7 percent. Dysbiosis, inflammation, immunosuppressive medications, and frequent hospitalizations associated with the disease increase susceptibility to C. diff, E. coli, and other infections. Symptoms of C. diff infection can mimic a Crohn’s disease flare-up. Prompt recognition and treatment are crucial, as this infection can be life-threatening, extend hospital stays, and worsen Crohn’s disease.

Fertility, Pregnancy, and Childbirth Complications

Having Crohn’s disease or taking medications for it can lead to various complications before and during pregnancy and childbirth, including:

- Placenta issues: Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy during pregnancy has been linked to a higher chance of placenta previa. In this condition, the placenta covers the cervix, which may cause severe bleeding during delivery.

- Preterm birth and small babies: There is a higher occurrence of early water breaking in women taking anti-TNF, thiopurine, and 5-aminosalicylic acids (5-ASA) medications. Women with Crohn’s disease are more likely to have low-birth-weight babies and infants small for their gestational age. Maintaining remission and being steroid-free for at least three months before conception is advisable, with appropriate treatment continued during pregnancy. It is crucial to note that infants exposed to anti-TNF medications in utero should not receive live vaccines for the first nine months of life or until the drug concentrations are undetectable in their blood.

- Increased risk of Cesarean delivery: Active perianal disease, a history of intestinal or perianal surgeries, or taking anti-TNF therapies and immunomodulators can make a C-section more likely. Guidelines often recommend C-sections for active perianal disease to avoid complications during vaginal delivery. Some women may choose an elective C-section to prevent perineal damage.

- Fertility: Crohn’s disease and its treatments can affect fertility. Women over 30 with Crohn’s disease in the colon may experience faster follicle loss, reducing fertility. Pelvic surgeries and active disease further contribute to this complication. In men, certain medications and active diseases can also decrease fertility.

Medications

Several classes of medications, each with its own potential risks and benefits, are used to achieve these goals. Those recommended in the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines include:

- 5-Aminosalicylic acids (5-ASAs): Sulfasalazine has shown efficacy for treating Crohn’s disease in the colon in mild to moderate flares. The ACG advises against oral mesalamine because it has not demonstrated efficacy in inducing remission or healing.

- Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids such as prednisone and budesonide are potent anti-inflammatory agents that quickly control flare-up symptoms. However, evidence suggests they are ineffective in consistently achieving mucosal healing, with the ACG recommending they be used sparingly. Due to potential side effects, they are not recommended for long-term use.

- Immunomodulators: Medications like thiopurines (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine) and methotrexate may help reduce inflammation during a flare-up and maintain remission by suppressing the immune system. These drugs can take several months to show their full effects. Before starting a thiopurine, doctors will likely test one’s levels of an enzyme called thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT). This test ensures a person can metabolize the medication properly and helps avoid potential side effects, including bone marrow toxicity.

- Biologics: Anti-TNF agents such as infliximab, adalimumab, and vedolizumab suppress the immune system, targeting specific inflammatory pathways. They are typically prescribed for severe Crohn’s disease cases that don’t respond well to corticosteroids or immunomodulators. In children, these drugs may be used to induce remission quickly and prevent long-term bowel damage. Combining infliximab with thiopurines may work better than using either drug alone for patients new to infliximab and immunomodulators.

Since the ACG guidelines were issued in 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several new oral and biologic therapies for Crohn’s disease, including Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, anti-interleukin-23 (IL-23) agents, subcutaneous anti-TNF formulations, and Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1P) modulators.

Enteral Nutrition

Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) involves consuming only liquid nutritional formulas to reduce inflammation and induce remission, providing complete nutrition. EEN is commonly used as a first-line therapy in children and may be an option for those who do not respond to medication. However, adults may struggle to stick to EEN due to taste fatigue and lifestyle challenges. Long-term use may affect the gut microbiota, be costly, and affect quality of life and social interactions.

Surgery

Unfortunately, many people with Crohn’s disease do not achieve remission with medication, and up to 75 percent will need surgery at some point—often more than once. Surgery may be necessary if medications fail, complications occur, or if precancerous or cancerous lesions are found. Procedures can include removing parts of the rectum, colon, or intestine, widening or diverting sections of the intestine, or addressing a fistula.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) involves transferring stool from a healthy donor into a patient’s gastrointestinal tract to restore healthy gut bacteria. While FMT shows promising results for treating ulcerative colitis and increasing microbial diversity, its effectiveness in Crohn’s disease is less conclusive and still under investigation.

1. Rebalancing the Microbiome

Addressing gut dysbiosis is crucial. Evidence varies on whether beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium are increased or decreased in Crohn’s disease, so testing can help tailor probiotics and prebiotics to a person’s specific imbalances. Effective yeast strains like Saccharomyces cerevisiae boulardii (sometimes written as Saccharomyces boulardii) may yield reduced relapse rates and improved gut permeability when used with mesalamine.

2. Healing the Intestinal Lining

To support and heal the gut lining naturally, avoid personal food triggers and things like processed foods, gluten, dairy, and additives like emulsifiers and carrageenan that adversely affect the intestine. Consider nutrients like the following to help reduce intestinal permeability and promote intestinal healing:

- Butyrate

- Zinc

- Vitamin D3 (Test to optimize levels and avoid toxicity.)

Glutamine, commonly used for leaky gut, has not shown efficacy in Crohn’s disease, and at least one randomized controlled trial showed it can worsen the condition.

3. Reducing Inflammation

Fish oil, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, may help reduce inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Some studies have shown that supplementation can prevent relapses. Though research remains mixed about the benefits of supplementing fish oil, it is generally safe when taken as recommended and may help promote a better balance between omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

- Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) combined with partial enteral nutrition (PEN)

- Elemental diet, a liquid meal replacement that includes all necessary nutrients broken down into easily absorbable forms

- Semi-vegetarian (plant-based with occasional animal products, but no red meat)

- Low-fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet

- Mediterranean diet

- Autoimmune protocol (AIP) diet

- Specific carbohydrate diet (SCD)

Each diet emphasizes nutrient-dense whole foods and excludes processed foods and additives that may be inflammatory or harmful to the microbiome. They likely show benefits because they are less inflammatory than the typical Western diet. However, focusing on healing the gut and re-modulating the immune system is crucial so that a highly restrictive diet is not needed long-term.

4. Reducing Oxidative Stress

Antioxidants are necessary to reduce oxidative stress. Persistent oxidative stress in Crohn’s disease can deplete the cells’ resources and ability to produce antioxidants. Therefore, a diet rich in antioxidant foods and specific supplements can be beneficial. Some antioxidant-rich foods include berries, cruciferous vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, herbs, spices, and olive oil. A few of the many antioxidant supplements are vitamins C and E, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), coenzyme Q10, and curcumin.

- Emphasize fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and whole grains to support a healthy gut microbiome.

- Limit processed foods, refined carbs, saturated fats, and potential dietary triggers like gluten and dairy.

- Incorporate anti-inflammatory foods from the Mediterranean diet, such as olive oil, fatty fish, leafy greens, and tomatoes.

- Avoid smoking, as it increases oxidative stress, inflammation, and the risk of Crohn’s disease.

- Minimize exposure to heavy metals, pollutants, and other toxic substances.

- Practice stress management techniques like mindfulness, yoga, and meditation.

- Stay physically active and adequately hydrated to support digestion and overall health.

- Limit the use of NSAIDs and unnecessary antibiotics to protect the gut barrier and microbiome.

- Discuss nonhormonal alternatives to oral contraceptives with a health care provider.

- If applicable, breastfeed infants for at least three months, if possible, to help establish a balanced gut microbiome.

- If pregnant, opt for vaginal delivery when medically appropriate to help seed the infant’s microbiome.