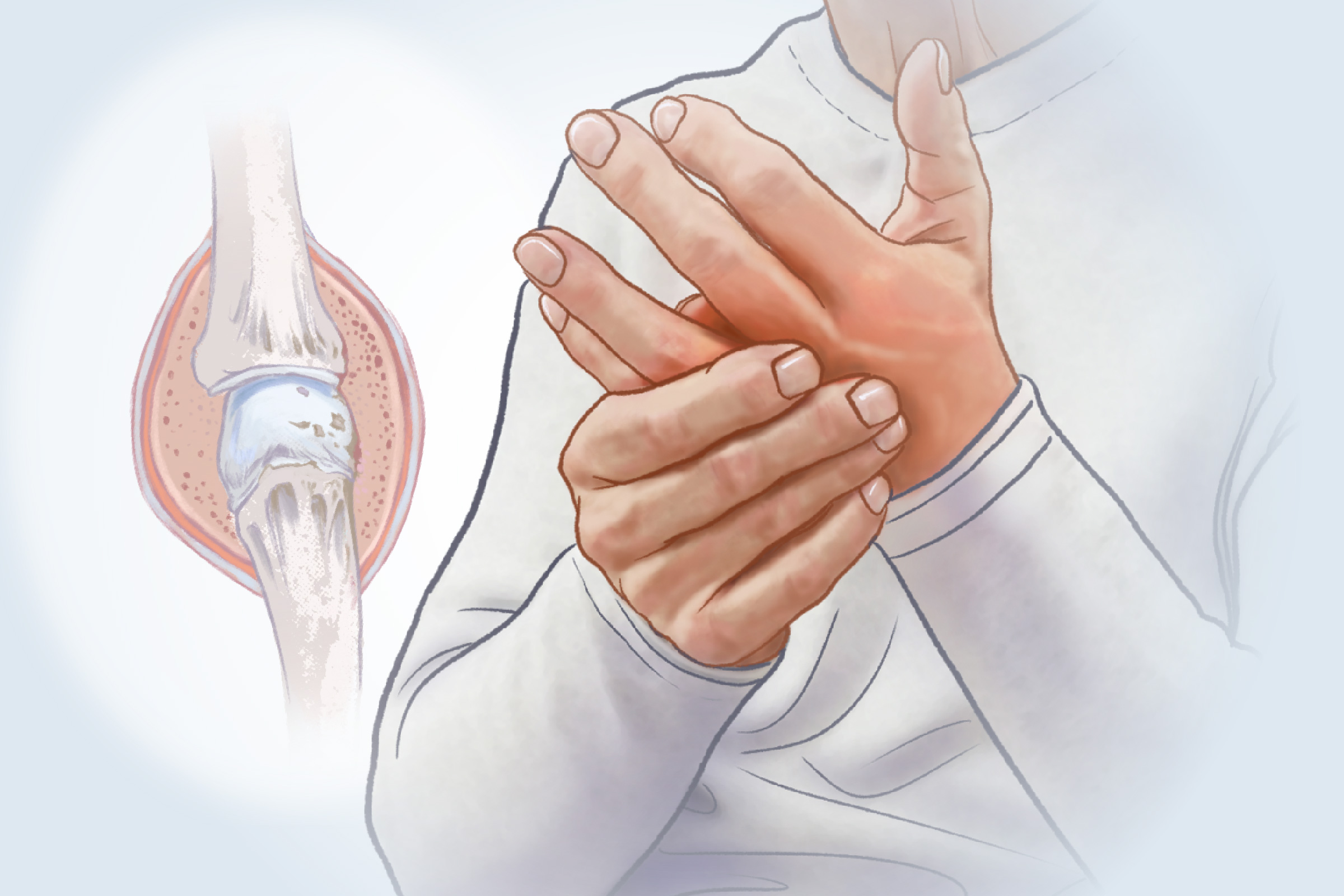

- Symmetrical joint pain and stiffness

- Morning stiffness of the joints lasting at least an hour

- Tenderness and swelling in the joints

As the disease progresses, symptoms might include a decreased range of motion and visible joint deformities.

- Persistent fatigue

- Low-grade fever

- Unintended weight loss

- Skin nodules

- Digestive issues

- Difficulty sleeping

- Inflammation affecting the lungs, heart, blood vessels, kidneys, and nerves

1. Genetic Factors

The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not yet fully understood. Genetics accounts for roughly 50 percent to 60 percent of rheumatoid arthritis risk, with numerous genetic variants identified. However, genes alone do not cause rheumatoid arthritis. Environmental triggers can activate these genes through epigenetic changes—molecular switches that turn genes on or off—creating a pathway from exposure to disease.

2. Environmental Triggers

Environmental triggers that have been linked to rheumatoid arthritis include:

Risk Factors

While the triggers above can directly initiate rheumatoid arthritis, the following characteristics increase the likelihood of developing it:

- Obesity: Research shows that excess body fat, especially around the abdomen, raises the risk of rheumatoid arthritis, worsens symptoms, increases disease activity, and may impair the response to certain medications. Body fat also releases chemicals that fuel inflammation, alter hormone balance, and put added stress on joints.

- Socioeconomic Status: Lower income and education levels are associated with increased rheumatoid arthritis risk, perhaps reflecting differences in smoking, workplace exposures, and stress.

- Sex: Women are about three times more likely to develop rheumatoid arthritis than men.

- Age: Rheumatoid arthritis can occur at any age, but most diagnoses occur between ages 30 and 50.

- Family History: Having a first-degree relative with rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk by about four times.

- Autoimmune Diseases: Having another autoimmune disease also raises the likelihood of developing rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions share a common underlying mechanism and have been observed in clinical studies to cluster together in the same person.

Blood Tests

Blood tests help confirm a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis, assess disease activity, and monitor how well treatments are working over time.

- Antibodies: The most clinically useful blood tests are rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP). RF targets the body’s own antibodies, while anti-CCP targets citrullinated proteins and is more specific for rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-CCP may appear years before symptoms begin.

- Inflammatory Markers: C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate measure systemic inflammation to help assess disease activity, though high levels can also occur with other inflammatory conditions.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): A CBC with differential checks red and white blood cells and platelets to detect complications or rule out other issues. Many people with rheumatoid arthritis develop anemia because inflammatory cytokines suppress red blood cell production and affect iron metabolism.

Imaging

Imaging studies help identify characteristic signs of rheumatoid arthritis, including symmetrical joint damage, bone thinning around the joints, joint space narrowing, swelling, cysts, and nodules. The following tools may be used:

- X-rays: Widely available and low cost, but less sensitive for early disease.

- Ultrasonography: More sensitive for early erosions and can show active inflammation.

- CT Scan: Rarely used due to radiation exposure, but offers high-resolution 3D imaging.

- MRI Scan: Most accurate for early detection and identifying bone marrow inflammation.

Functional Medicine Tests

Some functional medicine practitioners may use additional testing to identify underlying causes and guide personalized treatment plans. These may include comprehensive stool analysis to assess gut bacterial imbalances, vitamin D testing, heavy metal testing, hormone testing, food sensitivity testing, and methylation testing to evaluate how well the body handles detoxification and other key processes.

First-Line Therapies

Conventional first-line treatment for rheumatoid arthritis typically follows a stepped approach, starting with medications that manage pain and inflammation and progressing to drugs that slow disease activity.

- Pain Relief: Acetaminophen helps with pain but does not reduce inflammation.

- Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen help reduce pain and inflammation.

- Steroids: Glucocorticoids such as prednisone can quickly suppress immune responses and inflammation and are often used short-term or during flares.

- Traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs): DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine slow disease progression and may be used alone or in combination with biologics. These may take two to three months or longer to work.

Biologic and Targeted Therapies

If first-line therapies fail to control rheumatoid arthritis, treatment may progress to therapies that modify the disease process.

- Biologics: These medications block specific immune targets involved in rheumatoid arthritis, such as TNF, IL-6, B cells, or T-cell activation. Examples include etanercept, adalimumab, tocilizumab, rituximab, and abatacept.

- Targeted Synthetic DMARDs: Janus kinase inhibitors such as tofacitinib and baricitinib disrupt intracellular signaling pathways that drive inflammation.

Side effects of rheumatoid arthritis medications—from first-line drugs to biologic and targeted therapies—vary but may include a higher infection risk, liver dysfunction, blood abnormalities, gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and neurological effects.

Supportive Care

Supportive care focuses on preserving joint function, reducing pain and fatigue, and improving daily quality of life alongside medical treatment.

Traditional and Complementary Treatments

Other treatments that have been studied for their potential effects on inflammation and joint symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis include the following:

- Tripterygium Wilfordii, or Thunder God Vine, used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects in rheumatoid arthritis.

- Wuweiganlu extract, a Tibetan medicine, has been shown to reduce joint inflammation and damage.

- Research indicates that acupuncture may help reduce pain and stiffness and improve function in rheumatoid arthritis.

Like other medical treatments, these TCM and Tibetan therapies come with potential risks and side effects, and should only be used under the supervision of a qualified practitioner.

Dietary Modifications

An anti-inflammatory, high-fiber diet is one of the most effective ways to support immune balance, reduce disease activity, and improve the microbiome in rheumatoid arthritis. Two dietary approaches in particular have shown benefit:

Foods to Avoid

Certain foods can increase inflammation, promote gut dysbiosis, or contribute to weight gain, which can worsen joint pain. For example, gluten—even in those without celiac disease—can increase intestinal permeability and immune activation. Research suggests a gluten‑free diet may reduce antibodies, improve symptoms, and lower disease activity in some people with rheumatoid arthritis.

- Processed foods

- Sugary foods and baked goods

- Fried foods and trans fats

- Seed oils

- Excess salt

- Red and processed meats

- Alcohol

Beneficial Nutrients and Compounds

Several nutrients and botanicals have demonstrated benefits for reducing rheumatoid arthritis symptoms, lowering inflammatory markers, and supporting immune balance.

- Borage Oil: Borage oil is rich in gamma-linolenic acid with anti-inflammatory effects and, in some studies, has shown benefits comparable to NSAIDs.

- Fish Oil: The omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) found in fish oil can reduce pain, morning stiffness, and inflammatory cytokines.

- Polyphenols: Compounds such as curcumin, quercetin, resveratrol, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) from green tea help regulate immune activity and provide antioxidant support.

- Boswellia: Resin from Boswellia serrata has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects in rheumatoid arthritis, including reduced pain and swelling and improved joint function.

- Ginger: Ginger has anti-inflammatory properties and has shown evidence for reducing disease activity.

- Vitamin D: Vitamin D plays a key role in immune function; deficiency is common in rheumatoid arthritis and is associated with increased disease activity.

- Antioxidants: Selenium, zinc, and vitamins A, C, and E help counter oxidative stress, which contributes to joint damage.

- Bone-Support Nutrients: Calcium, magnesium, and vitamins D and K help maintain bone density and counter bone loss from rheumatoid arthritis and long-term steroid use.

Nutrients That Support Gut Barrier Integrity

Several nutrients can support intestinal lining repair, reduce permeability, and help restore immune balance. With professional guidance, these can be obtained through diet or supplementation, and include:

- Glutamine: An amino acid found in protein-rich foods such as meat, fish, and eggs.

- Zinc: A mineral found in oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, and beans.

- Butyrate: A short-chain fatty acid found in butter and ghee and made when gut bacteria ferment fiber from vegetables and other plant foods.

- Vitamin D: Found in fatty fish and egg yolks and made in the body after sunlight exposure.

Other Supportive Approaches

Several supportive therapies have been studied for their potential to reduce pain and stiffness, improve mobility, or support symptom management in rheumatoid arthritis. These include:

- Yoga: Studies on yoga for rheumatoid arthritis show improvements in pain, stiffness, function, and quality of life.

- Exercise: Regular, low-impact movement such as walking, gentle stretching, or light resistance exercises can improve pain, mobility, and physical function.

- Heat and Cold Therapy: At-home heat applications, such as warm packs or warm showers, may help loosen stiff joints and relax muscles, while cold applications, such as ice packs, may help reduce swelling and numb sharp pain.

- Massage: Research on Swedish massage, aromatherapy massage, and foot reflexology suggests potential benefits for pain reduction and improved function in rheumatoid arthritis.

Many other natural approaches exist, and individual responses vary. Even natural compounds may cause side effects, interact with medications, or be inappropriate for certain conditions. Always consult your health care provider or pharmacist for personalized guidance.

- Know Your Personal Risk: In people with a family history of rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmunity, testing for anti-CCP antibodies may help identify rheumatoid arthritis earlier, when treatment and lifestyle changes have the best chance of preventing or slowing progressive joint damage. Some functional medicine practitioners also use expanded immune-reactivity panels to evaluate broader autoimmune risk.

- Smoking Cessation: Avoiding smoking and secondhand smoke exposure, as smoking is the strongest modifiable environmental risk factor.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight to reduce inflammatory burden and joint stress.

- Anti-Inflammatory Diet: Following a dietary pattern that reduces systemic inflammation and supports immune balance.

- Toxic Exposure Avoidance: Minimizing exposure to air pollution and toxic chemicals.

- Vitamin D Optimization: Maintaining adequate vitamin D levels through sunlight exposure, diet, or supplementation.

- Gut Health Support: Supporting healthy microbial balance and gut barrier integrity.

- Stress Management: Using techniques that reduce chronic psychological stress.

- Oral Hygiene: Maintaining good dental health to reduce the risk of periodontal disease.

- Protective Supplementation: Working with a qualified practitioner to identify beneficial nutrients based on individual needs and risk factors.

These lifestyle modifications can also lower the risk of other chronic conditions and may play an important role in managing rheumatoid arthritis and reducing complications.

Cardiovascular Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis more than doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease. Chronic inflammation accelerates atherosclerosis, or plaque buildup in the arteries, and raises the risk of heart attack, congestive heart failure, and pericarditis, or inflammation of the heart lining.

Pulmonary Complications

Lung involvement is frequent and may include:

- Interstitial Lung Disease: Scarring of lung tissue that interferes with oxygen exchange.

- Pulmonary Fibrosis: Progressive lung scarring that can impair breathing.

- Pleuritis and Pleural Effusions: Inflammation of the lung lining or fluid buildup around the lungs.

Bone Health

Systemic inflammation and long-term steroid use can accelerate bone loss, contributing to osteoporosis in about one-third of people with rheumatoid arthritis, and increasing fracture risk.

Eye Complications

Eye involvement, if untreated, can cause pain, light sensitivity, and vision problems. Manifestations may include:

- Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca: Significant eye dryness.

- Episcleritis and Scleritis: Inflammation of the outer layers of the eye.

- Keratitis: Inflammation of the cornea.

- Secondary Sjögren’s Syndrome: An autoimmune condition affecting tear and saliva production.

Neurological Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect the nervous system through compressed nerves, reduced blood flow, medication effects, or direct autoimmune activity. Common manifestations include:

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Compression of the median nerve at the wrist.

- Peripheral Neuropathy: Nerve damage causing numbness, tingling, or weakness.

- Cervical Myelopathy: Spinal cord compression caused by neck instability.

Skin Manifestations

Skin-related complications may include:

- Rheumatoid Nodules: Firm lumps that develop over pressure points.

- Periungual Inflammation: Redness and inflammation around the nails.

- Rheumatoid Vasculitis: Inflammation of blood vessels that can cause purplish spots, ulcers, or—in severe cases—digital gangrene because of reduced blood flow.

Blood-Related Complications

Chronic inflammation and some rheumatoid arthritis medications can lead to blood-related complications, including:

- Anemia: Reduced red blood cell production linked to inflammation.

- Felty’s Syndrome: A triad of an enlarged spleen, low white blood cell count, and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Abnormal Blood Cell Counts: Conditions such as neutropenia (low neutrophil count), eosinophilia (elevated eosinophils), thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), and thrombocytosis (elevated platelets linked to active inflammation).

- Increased Risk of Blood Clots: A higher risk of blood clots, particularly when platelet levels are elevated.

- Increased Risk of Cancer: A higher risk of certain cancers, including lymphoma (cancer of the lymphatic system).

Gastrointestinal Complications

While many gastrointestinal issues arise from medication effects, rheumatoid arthritis itself can lead to rare, serious problems, including:

- Rheumatoid Vasculitis: Inflammation of the blood vessels manifesting in the intestines, a rare but serious form of systemic vasculitis that can cause ischemia or bowel perforation.

- Amyloid A Amyloidosis: Abnormal protein deposits in the gastrointestinal tract that can cause diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, and malabsorption.

Other Systemic Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect multiple systems beyond the joints, leading to complications that benefit from early recognition and ongoing monitoring.

- Oral Manifestations: Salivary gland swelling and dry mouth.

- Renal Complications: Kidney involvement, including glomerulonephritis or interstitial renal disease, affecting up to one-quarter of people with rheumatoid arthritis.

- Sleep Disruption: Pain and stiffness that interfere with sleep, along with inflammation that disrupts normal sleep-wake regulation.