COVELO, Calif.—Driving up the steep and windy road from his station in Ukiah, Mendocino County Sheriff Matt Kendall stops his pickup at a pullout overlooking California’s Round Valley.

“It’s where the trouble begins and never ends,” he told The Epoch Times.

Native American sovereignty and California’s policies that shield illegal immigrants have allowed Mexican drug cartels to swoop in on tribal lands of the Round Valley Indian Tribes, a confederation of several tribes, the sheriff said.

The valley, known for illegal marijuana grows on tribal lands, is remote and surrounded by forested mountainous terrain. It’s a patchwork of tribal lands and those sold off to private owners years ago.

Kendall, 56, grew up here in the 1970s. During the drive to Covelo, an isolated town in the valley, he talks about how the times have changed over the decades.

“Back in the ’60s and ’70s, it was a beautiful place—a lot of freedom here,” he said. “When we were kids, we'd be riding our horses and having fun. Every kid in this valley had a horse. We’d go out to the river. All of us had summertime jobs, hauling hay and cutting firewood.”

His nostalgic journey ends abruptly as he passes a burned-out building with murals of missing women on its walls—a stark reminder of the violence that plagues the valley. Other banners along the road display their names and faces, including that of Khadijah Rose Britton, a native American woman who, according to the FBI, was last seen in Covelo being kidnapped at gunpoint in 2018.

Today, Kendall says that “there’s a little bit of farming, and then just tons and tons of marijuana, and pretty much all of it is illegal.”

“We see a lot of Hispanics here when there is no work, no sawmill jobs, no grapes, no vineyards, and not much logging,” he said. “They’re all here taking orders to grow marijuana, and a lot of it’s happening on tribal lands.”

He estimates that up to 80 percent of the illegal marijuana in Mendocino County is grown on the valley floor—most of it on tribal lands—based on aerial surveillance and satellite imagery revealing a vast network of illegal grow operations.

Signs are displayed for a missing woman outside of Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Mexican Cartels

Kendall first encountered Mexican cartels in his county in the mid-1990s.

“I got shot at right over there in a Mexican grow,” he said, pointing to a footpath through the brush.

“A guy pops out of a tent with a 12-gauge and I’m screaming at him in English and Spanish, ‘Drop it or I’m going to drop you!’ and he takes off running and gets a round off at me over his shoulder.”

Years ago, a group of Hispanics growing marijuana in the hills “were digging up artifacts and just tearing things up,” Kendall said.

“We hit this place with search warrants years ago. We got thousands of plants,” he said.

Today, even though the cartels and the laborers who work for them cultivating and harvesting the illicit marijuana are mostly illegal immigrants, Kendall is not legally allowed to call in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) because of state Senate Bill 54, signed in 2018 by then-Gov. Jerry Brown.

The law prohibits state and local law enforcement from using their resources to assist federal immigration enforcement agencies, including ICE, and forbids them from asking about a person’s immigration status or sharing confidential information with federal agents.

Today, two competing Mexican cartels, Jalisco New Generation Cartel and La Familia Michoacana, are exploiting California’s sanctuary state policies and the sovereignty of native tribes to illegally grow marijuana in the county, the sheriff said.

The cartels have tagged their territory with spray paint in different areas of the valley, he said.

Mendocino County Sheriff Matthew Kendall drives outside Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. Mexican cartels and the related crime have become a major problem in the county. Kendall cites illegal marijuana grows on tribal lands as one of the most serious issues. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Shootouts Are Common

“We know that we’ve got some hard hitters from a cartel in the Mexican state of Michoacán,” said Kendall.

He said he suspects that a shootout in the hills in May was infighting among La Familia Michoacana members, known for gun battles in the streets of Mexico.

A roadside shrine marks the site where Jorge M. Zavala Estrella, 30, was shot and killed in the shootout.

“These guys had some bad blood over money and grow operations, and they met nose-to-nose right up here,” he said, pointing out the spot on Hulls Valley Road.

Another man was shot about a dozen times and was bleeding out near the edge of the road when deputies found him. He was airlifted to an out-of-county hospital and survived, the sheriff said.

A third and fourth suspect were also involved in the gun battle, and the homicide investigation is ongoing, Kendall said.

In another shootout in 2022 involving cartel members, Kendall estimates about 300 shots were fired.

“There was brass collected everywhere,” he said. “We never found a drop of blood—not a single body.”

Shootouts are common, he said—“about three or four every year”—and firearms used include AK-47s, AR-15s, and M-16s.

Kendall said he suspects that the money for infrastructure to grow illegal marijuana is coming from south of the border because the toxic chemical containers are labeled in Spanish and most local residents can’t afford to pay for hoop houses and to haul in soil and water.

“Somebody’s putting up the money for this,” he said. “There are millions of dollars being poured into the marijuana industry up here.”

(Top) A marijuana grow operation outside of Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. Mendocino County Sheriff Matthew Kendall said some illegal immigrants who cannot afford to pay Mexican cartels’ smuggling fees end up working in marijuana cultivation to settle their debts. (Bottom) A marijuana farm outside of Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Narco-slavery

The Biden administration’s “wide open” border policies made things worse in Mendocino, he said.

“I’m not playing partisan politics here,” Kendall said. “It’s a fact. Borders were open.”

Illegal immigrants who couldn’t pay the full fare to Mexican cartels to cross into the United States fell into debt with the Mexican cartels, and much of that debt is being worked off in the marijuana grows, Kendall said.

Over the past few years, Kendall’s deputies have seen an increase in human trafficking cases as the cartels bring in more illegal immigrants to cultivate, trim, and harvest the illegal marijuana crops.

“It’s sex trafficking, it’s labor trafficking, it’s narco-slavery,” he said.

One victim told Kendall that after he crossed the border from Mexico into the United States, he was picked up in California and informed by the driver working for a cartel that he would be taken to Washington state to work in the “logging industry.”

“I’ve spoken with a lot of people in marijuana grows—once they’re caught—who have been trafficked and didn’t realize it,” he said.

Kendall found the man months later in Mendocino, one of three Northern California counties—with Trinity and Humboldt—that make up the Emerald Triangle, an area long known for cannabis cultivation.

“He’s in the middle of the forest, in the middle of nowhere, in a weed grow. He has no idea where he is. He thinks he’s in the state of Washington. He doesn’t know anyone, except for a couple of other clowns that are also working there. He doesn’t know how to get out of there,” the sheriff said.

“So where do you start to find your way home? He’s in a foreign country. He doesn’t speak the language, and these guys show up and bring food now and then. And whether he knows it or not, he has been trafficked.”

The man told him the cartels promised to pay him for his labor at the end of the growing season but didn’t, Kendall said.

“A lot of these folks I’ve spoken to aren’t getting paid at all,” he said. “We had two people wander out of the brush—husband and wife. They weren’t getting paid. They wanted to leave, and the gate was locked, and the boss goes and lights their car on fire.”

Many of the laborers at illegal grow sites in several California counties live in squalor at makeshift camps where their basic human needs are not being met, and they aren’t there of their own free will, he said.

“They’re scared to death of the cartels,” Kendall said. “They wind up here, but they’re still under that control.”

A marijuana grow operation near Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. Sheriff Kendall said many laborers at these grow sites live in poor conditions and may be working against their will. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

‘We’re Not Mayberry’

The sheriff’s department is underfunded, understaffed, and under-equipped to deal with all the crime related to illegal marijuana grow operations, he said.

“This is cartel violence that not even the United States government seems to be able to handle, and we’re expected to take it on when we’ve got six deputies for 3,500 square miles,” Kendall said.

“We’re not Mayberry,” he said, referring to the quaint, fictional town from “The Andy Griffith Show.” “I wish we were because we’d have enough personnel to handle Mayberry.”

Kendall said he isn’t looking forward to the coming weeks of harvest season, which usually means more robberies, murders, and mayhem.

“There’s cash, there’s marijuana, there’s greed,” he said.

Tribes Sue Sheriff

Tribal sovereignty also poses a challenge for law enforcement. In April, the Round Valley Indian Tribes and three residents of the reservation filed a lawsuit against Kendall and other law enforcement agencies over raids that occurred on tribal land in July 2024. The lawsuit alleges that sheriff’s deputies failed to produce valid search warrants and illegally destroyed medicinal cannabis gardens and cultivation.

Kendall wouldn’t comment on specifics related to the case but said the tribes are trying to assert their sovereignty over marijuana grown on tribal lands.

The sheriff said that although the tribes “should have sovereignty,” he has received complaints from tribal members saying the reservation has been overrun by cartels.

“We’ve had some really good, forward-thinking tribal leaders over the years—really good people—but there’s a little ebb and flow where we'll get some people in who are making money off the marijuana, and the rules change,” Kendall said.

Reservations are often the canary in the coal mine.

“If something goes south there, because it’s a very close, tight-knit community, it’s going to go south across the entire county,” he said.

Kendall said that partisan politics are getting in the way of law enforcement and public safety but that he does his best to stay out of the fray.

“I’m careful what I say because I don’t want to alienate people, but I still have to tell the truth,” he said, adding that one of the more important things he can do is call out corruption and deception.

“There’s a very small portion of people who are making money on it, and they are being bullies and creeps, intimidators, knee-cappers, to the good people.”

Kendall said that he’s repeatedly called California Gov. Gavin Newsom but that the governor won’t return his calls.

Mendocino County Sheriff Matthew Kendall looks down a road in Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. Kendall said marijuana legalization in the state has failed to curb the black market or support legal growers, arguing that penalties remain too light to deter illegal cultivation. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

“Kids up here are smoking pot at 10, 11, and 12 years old,” he said. “We have pounds of methamphetamine, fentanyl, and heroin. Anything that you can think of is happening on this reservation.”

In 2021, 47 people died from accidental opioid overdose in the county, a rate three times higher than the state average. In 2023, the county’s rate for all drug overdoses was 41.2 deaths per 100,000, significantly more than many other counties.

Mendocino County District 3 Supervisor John Haschak didn’t respond to The Epoch Times’ request for comment.

Legalization of Cannabis

Cannabis proponents who claimed that legalizing marijuana would eliminate the black market and its criminal element couldn’t have been more wrong, Kendall said.

“The black market is killing the white market,” he said.

When the state legalized marijuana in 2016, Kendall said lawmakers should have imposed stiffer penalties for those growing weed illegally: “Why didn’t they say if you jump through the hoops, you’re going to be legal, and if you don’t jump through the hoops, we’re going to throw [you] in prison?”

Instead, the state is tolerating the growth of the black market at the expense of legal cannabis growers who can’t compete with much lower black market prices, he said.

Illegal growers view the $500 fine for cultivating illegal marijuana as the cost of doing business. For example, the driver of a truck loaded with 4,000 pounds of illegal marijuana would be fined $500 total, not per plant or per pound, Kendall said.

“It’s a joke,” he said.

Cartels Exploiting Tribes

A longtime resident of Round Valley who spoke to The Epoch Times on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation said Mexican cartels are exploiting tribal members while the tribal council “turns a blind eye.”

It’s easy to spot the cartel bosses because they look “citified” and “unapproachable,” the source said.

“They drive really expensive vehicles. They get out with polished clothes and gold jewelry. You can tell. They’re different,” the source said. “You see them now and then roll into town. They don’t live here.”

Cartels offered some tribal members as much as $40,000 up front to use their land and water for one year, while others were promised cars or a 30 percent cut of the profits from the illegal pot, the source said. But by the second or third year, the cartels took all the profits and told the tribal members the deals were off the table.

“A lot of people will take the money and then they can’t get out of it,” the source said, because once the cartels gain a foothold on a property, “they won’t leave.”

“Nobody wants to talk” because too many people “have their hands in the same money bag,” and the cartels know who’s who on the reservation, including family connections, where people work, which elders may live alone, and which children may walk to school, the source said.

“Who are they going to tell when they’re scared and scared for their families?” the source said.

The cartels are also paying tribal members in harder drugs, mostly “meth and fentanyl,” according to the source.

Illegal grow operations are known to cause extensive environmental damage, including toxic contamination from banned foreign pesticides and rodenticides in the soil, but the tribal council has ignored these complaints, the source said.

Farmers grow Marijuana outside of Covelo, Calif., on Oct. 9, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

“They did nothing,” the source said. “There’s trash everywhere, and wherever there has been a grow, you cannot even use the land again. It’s horrible.”

Lewis “Bill” Whipple, tribal council president, and Robert “Bob” Whipple, treasurer, did not respond to The Epoch Times’ request for comment.

About half of the Round Valley tribal members have left the reservation, and many parents who have remained are sending their children to schools outside the reservation because it’s too dangerous, the source said.

Nobody listens to tribal members who want to see an end to the “fast money and drug peddling,” the source said.

Robberies and assaults tied to the illegal grows are common, and gunfire, including from large-caliber weapons, often echoes through the valley at night, the source said.

“There is so much I want to say, but I’m scared,” the source said. “There’s so much cartel activity. Tribal land is no longer safe.”

Because marijuana is illegal under federal law, “there’s been talk of calling federal marshals to come in,” the source said, “but [the] tribal government doesn’t want the federal marshals in [the area] at all.”

The Epoch Times reached out to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for comment but received no response.

Federal Help

A former Round Valley Indian Tribes council member, who asked not be named for fear of retaliation from cartels, suggested that ICE could step in to remove cartel members and illegal immigrants who are exploiting tribal members on native lands.

“There’s a problem when you have people move from Soyapango, the highest crime and drug capital in the world, and come straight to Covelo,” the source told The Epoch Times.

Soyapango, a sprawling municipality near El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador, is known historically for the presence of violent gangs such as MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and its rival, the 18th Street Gang (Barrio 18). In 2022, President Nayib Bukele ordered a military offensive, deploying 10,000 soldiers and police to surround Soyapango and round up tens of thousands of suspected gang members.

Eradicating cartels from tribal lands in Round Valley would mean asking the federal government to send in federal agents, but in the past, that idea has been rejected by the tribes, the former tribal council member said.

“Many tribal members and even some tribal leaders have allowed cartels to move in and grow illegal weed for financial benefit,” the source said. “Even though they’re bullied ... and it’s bad for the community, it does support some of the elders.”

Some tribal members see illegal immigrants as “people of color” and feel they “should back them—the illegal immigrants—completely,” the source said. Meanwhile, the cartel culture and illegal grow operations are destroying the community, environment, and native way of life.

Mendocino County Jail in Ukiah, Calif, on Oct. 9, 2025. Since Gov. Gavin Newsom established the Unified Cannabis Enforcement Taskforce in 2022, 47 warrants have been served in Mendocino County, leading to four arrests and the seizure of 54 firearms and an estimated $65 billion worth of marijuana plants and harvested cannabis. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Tribes have seen funding cuts over the past four years, when they could have used the money to create jobs, the source said.

“I feel that a lot of the funding that went to illegal immigrants was taken from funds that should have been given to native Americans to help them build a foundation for their tribes,” the source said.

Because job opportunities for those living on the reservation are sparse, the people often live on social assistance or Social Security.

“There’s nothing to do here. So what are you going to do with your mind, your thoughts? The easiest way out of the valley is to get high,” the source said.

Alcoholism and drug addiction rates among indigenous peoples are already high, and cartels supplying harder drugs such as meth and fentanyl aren’t helping, the source said.

Additionally, nobody in Covelo will talk to authorities about missing and murdered women and girls, the former tribal council member said.

“I’m talking about the ones that get taken, raped, beaten, left on the side of the road, that nobody hears about,” the source said. “They can’t tell anybody because their families are on the line. They can’t come forward or get out of Covelo. Nobody can help them.”

Cannabis Control

Newsom’s office referred an inquiry to the California Department of Cannabis Control (DCC).

“Illegal cannabis grows on federal lands, including tribal trust lands and National Forests, are a serious issue. Any illegal cannabis grows put people at risk, harm the environment, and undercut the legal market,” Jordan Traverso, the DCC’s deputy director of public affairs, wrote in an email to The Epoch Times.

California doesn’t have “civil-regulatory jurisdiction over cannabis cultivation on tribal land,” but if evidence of crimes such as forced labor, illegal pesticide use, or money laundering surfaces, then state and local law enforcement agencies have authority to investigate, according to the DCC.

Federal agencies have authority to investigate and arrest people for criminal activity regardless of a suspect’s citizenship or immigration status, including at grow sites on tribal or other lands under federal jurisdiction, according to Traverso.

“California’s laws do not prevent the federal government from enforcing federal immigration law, including entry into the United States,” she wrote.

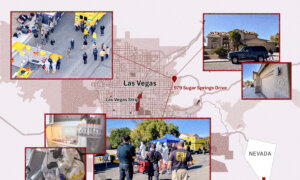

Since Newsom established the statewide Unified Cannabis Enforcement Taskforce in 2022, 47 warrants have been served in Mendocino County, resulting in four arrests and the seizure of 54 firearms, 67,368 pounds of harvested cannabis, and 94,066 marijuana plants valued at $65 billion, according to the DCC.

A firearm seized by the Mendocino County Sheriff’s Department during a raid on an illegal cannabis grow site in Northern California. Since Gov. Gavin Newsom established the Unified Cannabis Enforcement Taskforce in 2022, 47 warrants have been served in Mendocino County, leading to four arrests and the seizure of 54 firearms and an estimated $65 billion worth of marijuana plants and harvested cannabis, according to the Department of Cannabis Control. (Courtesy of the Mendocino County Sheriff’s Department)

More than half of those warrants were served in Covelo, and nine each were served in Potter Valley and Laytonville. Two were served in Ukiah and one in Dos Rios.

On Sept. 25, 4,044 cannabis plants and 679.86 pounds of processed cannabis found in Covelo were destroyed, according to the DCC.

In mid-August, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, in conjunction with other law enforcement agencies, served 21 search warrants and conducted raids in Mendocino County to “investigate the illicit cultivation of cannabis with impacts on sensitive fish and wildlife habitat.”

The raids eradicated more than 46,000 cannabis plants and destroyed more than 13,600 pounds of processed cannabis.

Tens of thousands of illegal plants may sound like a lot, Kendall said, but if only 46,000 plants out of an estimated 8 million to 10 million plants in the county are seized, it’s “a drop in the bucket.”