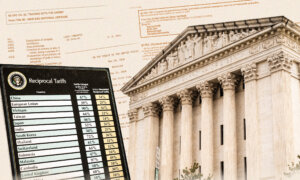

President Donald Trump said on Feb. 20 that he will issue an executive order to create a 10 percent “global tariff,” announced shortly after the Supreme Court invalidated his reciprocal duties on U.S. trading partners.

The new tariff would be added to existing import levies, which remain in place under the court’s decision.

“The good news is that there are methods, practices, statutes, and authorities, as recognized by the entire court in this terrible decision, and also recognized by Congress, which they refer to, that are even stronger than the IEEPA tariffs available to me as president of the United States,” Trump told reporters at a press briefing.

Section 122

Trump’s executive action will invoke Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974.

Section 122 allows the president to implement a tariff rate of up to 15 percent on countries that maintain “large and serious” trade surpluses with the United States. The measure also authorizes the president to introduce limits on the volume of foreign goods entering the country.

The tariff can be applied for 150 days. An extension will require the White House to seek congressional approval, which could be difficult, especially as the midterm elections near.

One of the key advantages of Section 122 is that it does not mandate the administration conduct a formal investigation to justify the tariffs.

The Trade Act of 1974 was first introduced in 1973 by Rep. Al Ullman (D‑Ore.) and was enacted in 1975 when President Gerald Ford signed it into law.

While it has been on the books for more than 50 years, it has never been invoked by a president.

Market watchers had widely anticipated that the White House would use Section 122.

“Section 122 offers the fastest path forward,” ING economists said in a Feb. 20 research note.

“Section 122 has never been invoked, but its balance-of-payments trigger clearly applies to major partners like China and Mexico. Think of it as a temporary patch while more durable options take shape.”

Section 301

Trump added that his team is using Section 301 to initiate a series of inquiries into possible unfair trade actions—steps that could ultimately produce new tariffs.

Section 301 permits the president expansive power to address unfair trade practices, including by using tariffs and sanctions.

U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer will also be allowed to probe and respond to policies from foreign governments that the White House considers violations of trade agreements with the United States.

“While that has not been difficult to prove in the case of China 301 tariffs, it won’t be as easy for broader tariffs across dozens of countries,” Jeff Buchbinder, chief equity strategist at LPL Financial, said in a note emailed to The Epoch Times.

Trump tapped Section 301 during his first term and applied it against China.

Other administrations have used it in the 1980s and 1990s, specifically against Japan as part of pressure tactics to force Tokyo to open its markets to U.S. goods.

“For longer-term tariffs, Section 301 investigations remain the primary tool,” the ING economists added.

President Donald Trump speaks during an event to announce new tariffs in the Rose Garden at the White House in Washington, on April 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

“These allow duties in response to unfair trade practices but require up to nine months of review before implementation.”

Higher Tariffs Could Come

The president warned that while the Supreme Court’s decision has brought “great certainty” to the economy, the next set of tariffs could potentially be higher.

“It depends, whatever we want them to be, but we want them to be fair for other countries,” he said.

“And you know, we have some countries that have treated us really badly for years, and it’s going to be high for them, and we have other countries that have been very good, and [those are] going to be very reasonable tariffs.”

U.S. stocks shrugged off these fears, with the leading benchmark index averages up across the board.

Yields on long-term Treasury securities were also little changed, despite the possible fiscal fallout from refunds and future tariff collections.

However, speaking at an Economic Club of Dallas event, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent stated revenues will not change very much.

“I can tell you that the total amount of revenue the Treasury will collect this year will be little changed,” Bessent said.

Trump’s tariffs were forecast to generate approximately $3 trillion over the next decade.

Economists at the Penn Wharton Budget Model estimated that more than $175 billion in tariff collections could be returned to U.S. importers.