The year ahead could be an opportunity for public schools to reexamine expensive and ineffective education technology vendor contracts and potentially reduce screen-based learning, some K–12 policy experts have forecast.

Virginia Gentles, parental rights director at the Defense of Freedom Institute, an education and workforce policy center, said that states and school districts in 2025 took major strides to rid classrooms of student cellphone disruptions but that there is still a long way to go to recover the loss of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic era now that nearly $190 billion in federal relief aid has been exhausted.

“We’re not done,” she told The Epoch Times. “We’re just beginning to acknowledge the commodification of kids’ attention.”

The next main focus should be on laptop computers and other tools for browsing the internet, Gentles said.

She said that 90 percent of K–12 districts provide the devices for every child or allow students to use their own.

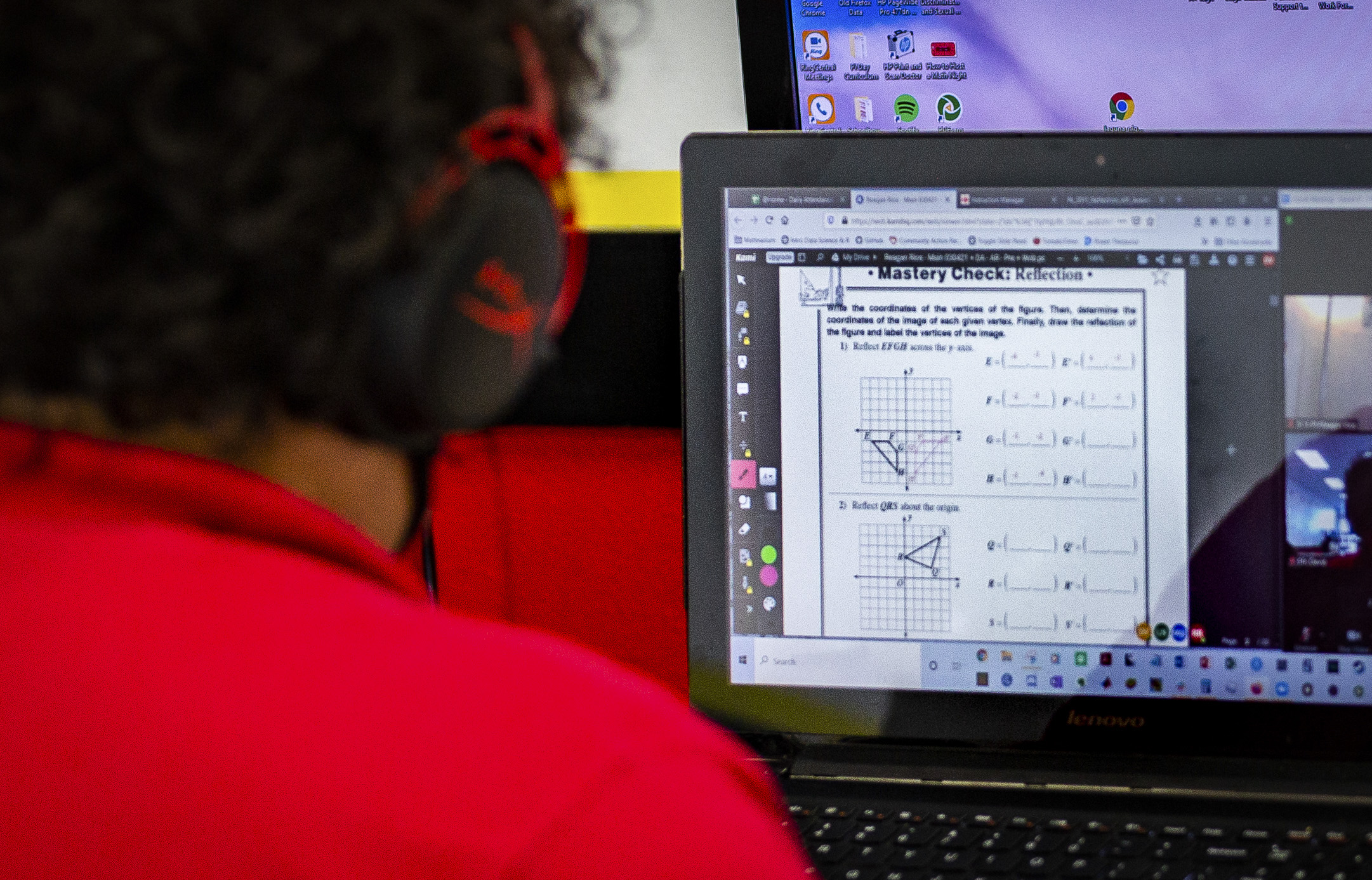

This one-to-one policy spread widely during the COVID-19 pandemic, following the extended closure of schools and the allocation of federal funds to support continued remote learning.

State test scores have continued to plummet since this policy was implemented, Gentles said.

She said that older students can access the same social media and sports betting apps that they used on their phones and that younger children who were essentially born with a device in hand struggle to write words on paper.

“Now is the time to fall out of love with this idea; 2026 is the time to take a look at this,” she said.

Gentles said she expects to testify before congressional committees on this topic and participate in policy center public roundtable discussions in the new year, as she did in recent months.

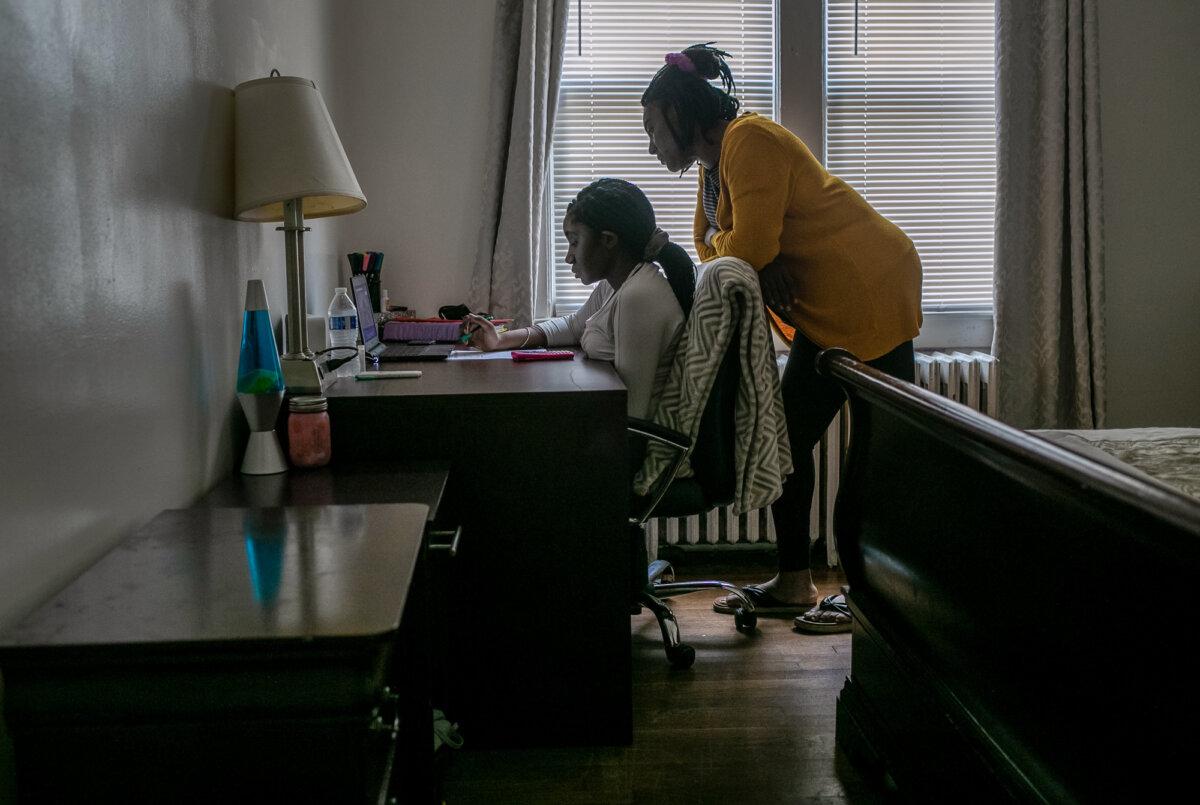

A student takes part in remote distance learning on a Chromebook with the help of her mother in Stamford, Conn., on Oct. 28, 2020. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Once attention is raised on this issue, legislation should follow, which was the case with cellphone restrictions, she said.

She said she isn’t calling for a total ban on student laptops but that more pen-and-paper assignments should return to classrooms, along with collaborative work, so that students aren’t continually looking at screens in isolation.

Not Making the Grade

Gentles grades the one-to-one arrangement at most public schools a “C,” representing the risks of increased cost, cheating, copying, compulsion, corruption, and commodification.

“The problem isn’t technology,” she said. “It’s ubiquitous technology.”

A look at headlines across the nation indicates that the rollout and continuation of the one-to-one policy has not been problem-free.

Many districts had problems keeping track of the devices and covering the costs of repairs and upgrades without continuing federal aid.

Bryce Fiedler, director of the Carolinas Academic Leadership Network, said it is “time to power down the Chromebook experiment.” The issue is twofold, he said: costs and quality of instruction.

“We can’t expect an 8-year-old to take great care of a laptop,” he told The Epoch Times. “On the learning side of this, it created 24/7 screen time. There’s never been more screen time per student in human history.”

Fiedler cited a 2024 analysis of 49 studies that found that students who read on paper consistently scored higher on comprehension tests than those who read the same material on screens, determining that digital reading leads to lower information retention and understanding.

Districts Overhaul 1-to-1 Policy

In the Burke County school district in North Carolina, the board of education passed a non-binding resolution ahead of this school year, asking teachers to blend digital instruction with in-person activities, such as group discussions.

Board of Education member Jamey Wycoff suggested it after his daughter, a first-grader, brought her school-issued Chromebook home to complete a homework assignment and revealed that much of the instruction at school involved looking at a screen.

“Other parents were asking the same question,” Wycoff told The Epoch Times.

He said that teachers and students have embraced the resolution, and leaders in his district have since consulted with their peers in eight other states, in addition to presenting it to state education organizations in Washington.

“It blew up like wildfire,” he said.

A student works on a project in New Rochelle, N.Y., on March 18, 2020. (John Moore/Getty Images)

In Pennsylvania, the Southern York County school district this academic year began phasing out its Chromebook program in grades K–4 in favor of a more balanced integration of technology such that digital learning will no longer be the centerpiece of instruction, Joe Wilson, a board of education member there, told The Epoch Times.

There is now one laptop for every pair of students, and the children aren’t allowed to bring them home. This shift has promoted student collaboration and small group instruction, Wilson said.

“Digital learning has not lived up to what it was expected to be,” he said, adding that his district had implemented a one-to-one laptop policy several years before the COVID-19 pandemic and that test scores across several grade levels remained stagnant or declined.

Questioning Ed-Tech Contracts

Gentles said districts in every state hurriedly spent their federal COVID-19 aid to buy laptops, software, and other digital learning tools, entering multi-year contracts with education technology vendors that renew automatically.

As the end of these five-year contracts approaches for many schools ahead of the 2026–2027 academic year, now is the time for K–12 leaders to stop and consider them, she said.

Many devices are equipped with filters that prevent students from accessing websites, and ed-tech vendors can provide additional services in that area.

Some school districts purchase “off-the-shelf” products without safeguarding student privacy.

The nonprofit Internet Safety Labs, which monitors K–12 technology use and policies, reported in August 2025 that off-the-shelf apps at schools outnumber licensed apps by a two-to-one margin.

When students, without a school license, create their own accounts to access software or websites, their privacy is compromised across devices at school or home, leaving them vulnerable to targeted advertisements.

“This is not a sufficient form of vetting to ensure student data privacy,” the report said. “Schools are subjecting students to unvetted and ungoverned technologies—sometimes more than 200 such technologies.”

Megan Kaul, a Seattle-based mother of two and a member of the national Mothers Against Media Addiction organization, declined to accept a school-issued device for her third-grade daughter because of privacy concerns. Her daughter can complete some in-class writing assignments on a laptop that doesn’t require log-ins. For reading assignments, she insists on books or printouts, not screens.

“An app for reading is just useless,” Kaul told The Epoch Times, “especially when there are so many books and libraries not being used.”

Fifth-grade students dissect owl pellets at Excel Academy Public Charter School in Washington on April 5, 2017. (Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images)

In the higher grades, she said, it’s infuriating to hear that students in science class watch a video of a class somewhere else doing a science experiment instead of doing the work themselves.

“Hands-on learning with real materials is superior every time,” she said. “We’re just glamorizing the idea of technology.”