In most U.S. public school districts, staffing continues to increase while student enrollment remains stagnant or declines, recent data indicate.

The situation is approaching a critical point as school boards begin the budget planning process for the 2026–2027 academic year. Federal post-COVID-19-pandemic relief grants are now exhausted, while enrollment-based state aid has decreased, forcing boards of education across the nation to grapple with the choice between layoffs and local property tax hikes, policy experts warn.

Nationally, K–12 public school enrollment decreased by nearly 900,500 students, or 1.9 percent, between 2015 and 2025, and staffing—including both teachers and support staff—increased by more than 700,000, or 11.8 percent, during the same time. That’s according to the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, which analyzes data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Virginia had the largest difference over the decade, with an 18.6 percent boost to staffing alongside a 2 percent enrollment drop.

The National Center for Education Statistics began releasing 2024–2025 state-level figures in the past two months, although updated information for every state is not yet available.

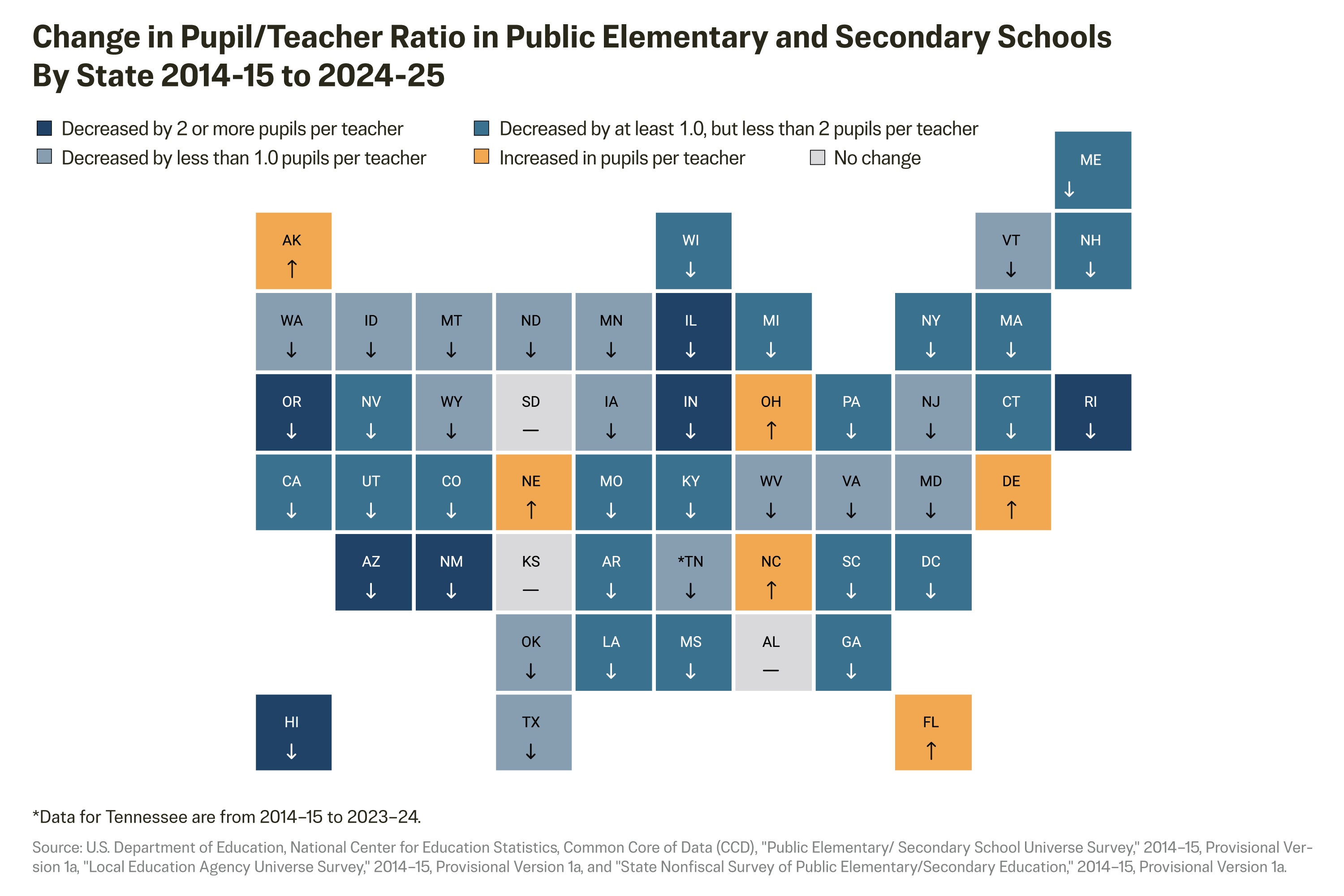

Across the country, National Center for Education Statistics data show that over the past decade, the number of students decreased and the number of teachers increased in more than 80 percent of states.

But the relatively modest increase in teaching staff was dwarfed by surging ranks of administrators and non-instructional staff.

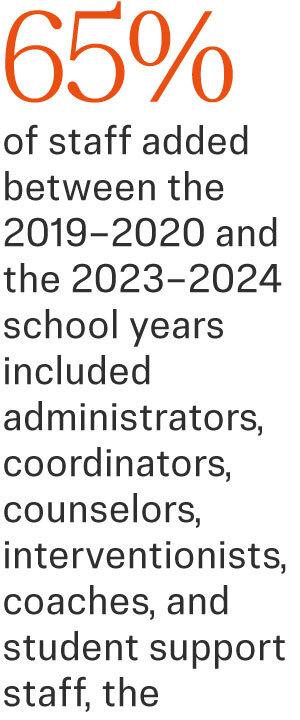

The Edunomics Lab, in its analysis of the 200,000 positions added between the 2019–2020 and the 2023–2024 school years, many of them through federal aid, reported that only 17 percent of those positions were teachers. Eighteen percent were aides, and the remaining 65 percent included administrators, coordinators, counselors, interventionists, coaches, and student support staff.

In states where student enrollment increased, it was minimal. The largest enrollment increase reported between 2020 and last year was 2 percent, in public schools in the District of Columbia, followed by Arkansas at 1.2 percent, according to Burbio, which tracks public school funding and spending.

Meanwhile, Edunomics data show that D.C. public schools experienced an 18 percent hike in the number of employees in that time period.

Most of the other states that had an increase in student enrollments—Utah, Oklahoma, Idaho, Maryland, Florida, Tennessee, Washington, North Dakota, and South Dakota—also reported disproportionately high staffing increases.

New Hampshire, Mississippi, and Wyoming all reported drops in both enrollment and staffing, according to the Edunomics Lab.

An elementary school teacher speaks to her students virtually at Hazelwood Elementary School in Louisville, Ky., on Jan. 11, 2022. In most U.S. public school districts, staffing continues to increase while student enrollment remains stagnant or declines, recent data indicate. (Jon Cherry/Getty Images)

At the District Level

The five largest districts in the nation—New York City, Los Angeles, Miami-Dade in Florida, Chicago, and Clark County in Nevada—have all lost students in the past several years, the Edunomics analysis shows, but Miami-Dade was the only one that reduced staffing.

Los Angeles reported the biggest differences through the 2022–2023 academic year. Its enrollment declined by nearly 26 percent while staffing increased by 19 percent, according to Burbio.

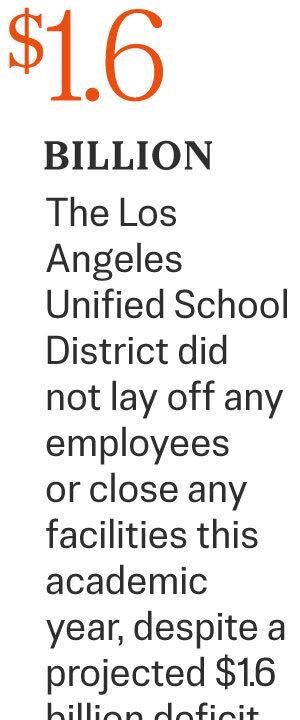

The Los Angeles Unified School District, which had an $18.8 billion budget for this academic year, did not lay off any employees or close any facilities, despite a projected $1.6 billion deficit that district leaders said would be addressed by 2028.

The district website indicates that the current spending plan provides an additional $25 million for its Black Student Achievement Program. That program employs seven regional directors, four district-level administrators, 15 instructional coordinators, and five administrative coordinators. The current budget also adds $2 million for LGBT awareness training. The district maintains a middle school magnet school for “social and gender equity” centered around social justice instruction, filmmaking courses, and daily yoga sessions.

“Budgets are a reflection of priorities, and even in difficult budget environments, we must choose to make decisions that protect our students, particularly our most vulnerable and those currently under attack by the federal government,” Kelly Gonez, Los Angeles Unified Board of Education member, said in a June 2025 statement.

“This resolution reflects the board’s shared commitment that we will approach any reductions in alignment with our values of equity, transparency, uplifting the critical work of our employees, and meeting students’ need.”

Burbio this month analyzed student–teacher and student–non-teaching staff ratios in the 25 largest districts in the country, comparing the 2019–2020 school year with 2024–2025. Among districts that reported numbers for that period, student–teacher ratios decreased in 15 districts, while student–staff ratios decreased in 17 districts.

California State Superintendent Tony Thurmond reads to second-graders at Nystrom Elementary School in Richmond, Calif., on May 17, 2022. An Edunomics analysis shows the five largest districts—New York, Los Angeles, Miami-Dade in Florida, Chicago, and Clark County in Las Vegas—all lost students in recent years, but only Miami-Dade reduced staffing. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Trending for Decades

The education nonprofit Reason Foundation, in a report released earlier this month, outlined the divergent pattern dating back to 1998. From that year through 2019, districts with declining enrollments reported staff increases of 25.5 percent per 100 existing students, along with a roughly 77 percent boost in salaries and benefits per employee.

The increase appears to be driven by job growth for both instructional and support staff, the report said, including guidance counselors, librarians/media specialists, administrators, and board of education support staff.

“This has happened because there’s a huge political cost to cutting teachers, cutting staff, and downsizing,” said David Hoyt, executive director of School Board for Academic Excellence, a national nonprofit agency that works with public school leaders. “But there’s a lot of administrative bloat.”

In the past decade, Hoyt told The Epoch Times, school districts added a significant number of administrators, along with information technology specialists, counselors, classroom aides assigned to individual special needs students in accordance with state laws or federal funding guidelines, and “interventionists” who are assigned to identify students who are falling behind and establish plans to help them catch up.

“Once you hire staff, it’s very hard to ratchet down,” Hoyt said. “From a budgeting standpoint, every year is going to be challenging for schools now.”

A pre-K student sits with a teacher outside a classroom at Yung Wing School P.S. 124 in New York on March 7, 2022. The Edunomics Lab found that of the roughly 200,000 positions added between the 2019–2020 and 2023–2024 school years, only 17 percent were teachers. (Michael Loccisano/Getty Images)

Trimming the Fat

The districts with the largest disparities between enrollment and staffing trends through 2024 were located in states that didn’t have right-to-work laws, meaning certain school employees are required to join unions, according to the Reason Foundation report. A strong union presence “tends to prioritize employment protections and compensation structures that inhibit performance-based pay and flexibility in resource allocation,” the report states.

“Reforms that prioritize instructional quality, flexible governance, and accountability rather than mere staffing will produce meaningful gains for students,” it states.

In its analysis of the 2026–2027 year budget planning process of 500 school districts, Burbio listed the top five cost-cutting priorities being considered: closing or consolidating school buildings; reducing staff; cutting elective courses in music, art, world languages, and other areas of study; reducing administrative and operational spending; and trimming or consolidating transportation services, including moving to public transit.

As an alternative to layoffs or building closures, the Edunomics Lab has advised that school districts can save money by increasing teachers’ course offerings to students rather than hiring additional staff, consolidating sports teams across multiple schools, making a plan to merge classrooms on a short-term basis when there’s a shortage of substitute teachers, and enlisting the help of community groups and parents to assist with library and athletic functions.

Administrative Bloat

Local districts are at the mercy of countless state and federal regulations for staffing, curriculum, facilities, and even student disciplinary requirements. Those regulations require schools to hire more employees and administrators to oversee compliance. These days, it’s not unusual for even smaller districts to have assistant superintendents in charge of instruction, special education, technology, and transportation, in addition to assistant principals for every grade level.

Shaka Mitchell, a senior fellow at the American Federation for Children, said outdated local regulations contribute to administrative bloat in public schools. For example, he said a public elementary school where he previously worked in Tennessee mandated having an employee to track and comply with space allocations, right down to the number of parking spaces, even if there was ample parking for employees or visitors and the students weren’t old enough to drive.

Mitchell also said many school districts across the country protect the most ineffective tenured teachers by allowing them to remain employed as some type of administrator.

“A lot of those added costs are things that don’t add value to what’s happening in the classroom,” he said.

An aerial view of the schoolyard at Frank McCoppin Elementary School in San Francisco on March 18, 2020. State and federal regulations require local school districts to hire more employees and administrators to oversee compliance. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Higher Staffing, Higher Taxes

When it comes to administrative bloat, property taxes—which provide a major funding source for school districts across the nation—are often the canary in the coal mine. Local governments provide 45 percent of all public K–12 education funding, and 80 percent of that share comes from property taxes, according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a Massachusetts-based think tank.

If staffing increases and student enrollment decreases—with a subsequent decrease in per-pupil reimbursement from the state—local tax levies are typically raised to fill the funding gap.

When state governments claw back funding from local governments and school districts, property owners often see drastic spikes in their tax bills on short notice.

Beth Blackmarr, a homeowner in Lakewood, Ohio, and media director for Citizens for Property Tax Reform, a grassroots organization, said most of the 31 school districts in the state’s Cuyahoga County have experienced enrollment declines in the past two decades, including a 50 percent drop in Cleveland city schools, while staffing levels and tax rates generally continue to rise.

“We do feel that good public schools are important to our communities, but we’re carrying an unfair share of the burden,” Blackmarr told The Epoch Times.

She said that the local property taxes on her small two-bedroom, 100-year-old bungalow total $4,600 a year, nearly triple the $1,580 she paid in 2008.

Blackmarr said moving from multiple districts to a county-wide school district would eliminate the staggering number of high-paid administrators and free up more money for classroom instruction at a time when it’s difficult to recruit and retain good teachers.

“Maybe there’s a better way to slice the pie,” she said.

A student arrives for classes at A. N. Pritzker Elementary School in Chicago on Jan. 12, 2022. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

School Choice

Declining U.S. birth rates and migration to other states are only part of the slumping enrollment equation. The other piece is school choice.

More than 18 percent of K–12 students in the United States attend charter schools, attend private schools, or are homeschooled, according to data compiled by EdChoice, an Indiana-based nonprofit. Those numbers are only expected to increase as many states and the federal government promote school choice.

Charter and private schools, especially those that serve low-income populations, have always operated with much tighter budgets and can’t afford administrative bloat, Mitchell said.

He said he thinks that public school budgets, whether decided on by voters or by local governments, will face more scrutiny than ever in the months and years to come, as parents increasingly remove their children from public schools, despite still paying taxes to fund the government education system.

“Parents notice when money isn’t getting pushed down to the classroom,” Mitchell told The Epoch Times. “I think you’re going to see school boards butt heads with the reality of what’s in the bank. There’s going to be some very tough decisions to make.”