With the new dietary guidelines for Americans still being finalized, President-elect Donald Trump has urged Robert F. Kennedy Jr., nominee for secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), to “go wild on the food,” signaling the potential for major shifts in national nutrition policy.

With diet-related illnesses costing the nation more than $1 trillion annually, the guidelines carry immense weight in shaping the eating habits—and health outcomes—of millions. Kennedy’s leadership could usher in significant changes, including stricter scrutiny of ultra-processed foods and a push to reduce corporate influence over federal health recommendations. As the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) prepares its report, Kennedy faces a rare opportunity to address the United States’ mounting diet-related health crisis.

Dietary Guidelines Defined

(Dietary Guidelines for Americans)

If you’ve ever eaten a school lunch, followed a doctor’s advice about healthy eating, or noticed public campaigns promoting nutrition, you’ve encountered the influence of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Updated every five years, these recommendations affect school cafeteria options, hospital menus, and the foods covered by assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

But the guidelines don’t appear out of thin air. Behind them is the DGAC, a panel of nutrition scientists and public health experts. Over two years, the committee reviews research, gathers public input, and compiles a report that informs the final recommendations.

The DGAC’s role is advisory.

“The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee reviews the science and makes recommendations,” Richard Mattes, a nutrition scientist and member of the 2020 DGAC panel, told The Epoch Times. Its report goes to the HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which finalize the guidelines.

This dynamic has led to controversy in the past. In 2020, the DGAC proposed stricter limits on added sugars and alcohol, but those suggestions were ultimately rejected. Now, the DGAC is preparing its report, a process expected to continue into 2025. If confirmed as HHS secretary, Kennedy will oversee implementation of the guidelines and help shape their final form.

A woman serves breakfast at a restaurant in North Carolina. (Yasuyoshi Chiba/ AFP via Getty Images)

Less Meat and Potatoes

The DGAC has proposed notable changes since 2020, emphasizing a shift toward plant-based eating and reduced reliance on animal-based foods. The recommendations prioritize plant-based proteins such as peas, beans, and lentils, reclassifying them entirely as protein foods rather than vegetables. The committee also highlights soy, seeds, and nuts as key protein sources and suggests reordering the protein group to reflect this emphasis—placing nuts and seeds first, followed by seafood, with poultry, eggs, and meat relegated to the last position.

Americans are also advised to limit overall red meat consumption. For those eating 2,200 or more calories daily, the DGAC suggests further cutting weekly meat, poultry, and egg intake by an additional 3.5 to 4 ounces compared with previous recommendations—roughly the size of a deck of cards or the palm of a hand.

The recommendations have ignited debate. The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association called the proposals “out-of-touch,” warning that they could harm groups such as older adults, adolescent girls, and women of childbearing age by raising the risk of nutrient deficiencies.

“This advice does not consider that plant-based proteins are not as complete as animal proteins—and therefore, not as digestible to people,” Nina Teicholz, a nutrition expert and author, wrote on her Substack, Unsettled Science. She added that plant proteins often contain extra carbohydrates, which could complicate efforts to combat obesity and diabetes.

The DGAC also suggests reducing starchy vegetable consumption, a proposal the National Potato Council called “unsupported by nutritional science.” Instead, the council advocated boosting vegetable intake across all categories.

The committee recommends six daily servings of grains, limiting refined grains to three. Despite health concerns about refined carbohydrates, the DGAC retained them in the guidelines for their nutrients such as iron and folate.

Teicholz questioned this decision, pointing out that red meat, a natural source of bioavailable heme iron and folate, is simultaneously being reduced.

The committee emphasizes a diet centered on whole foods—vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and fish—while also recommending water as the primary beverage and continuing to suggest low-fat or nonfat dairy products.

Americans are advised to limit overall red meat consumption. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

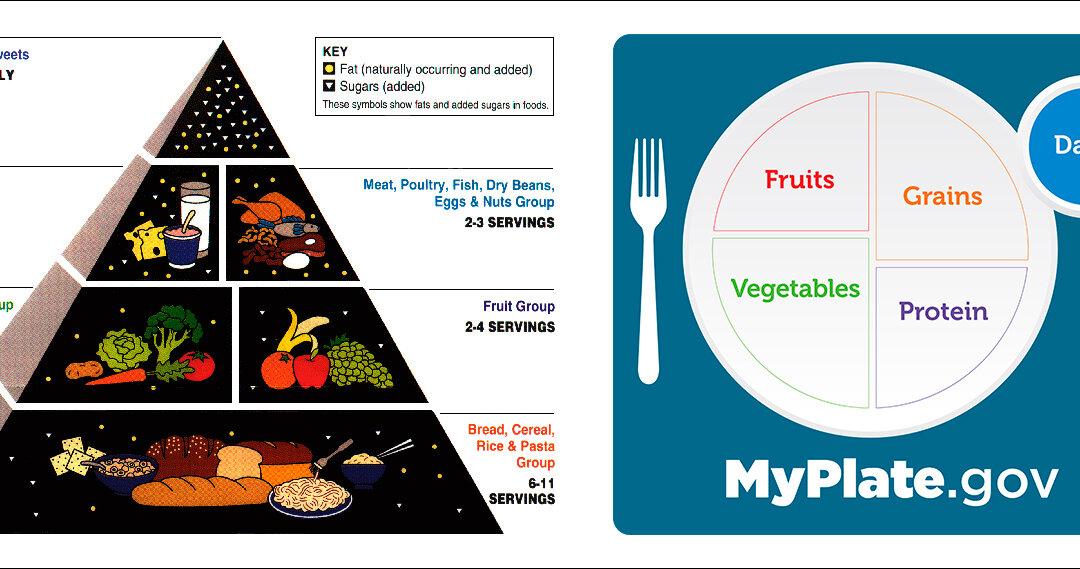

From Food Pyramid to Flawed Policy

For decades, the Dietary Guidelines have shaped how Americans eat, but their legacy is marked by controversy. Introduced in 1980, they shifted focus from overall nutrition to targeting fat intake, blaming dietary fat for heart disease and urging Americans to swap butter for margarine and adopt low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets.

Before the 1980 guidelines, Americans consumed about 45 percent of their calories from fat. The new recommendations reduced this to 30 percent while suggesting that carbohydrates should make up 55 percent to 60 percent of daily calories—primarily from grains. This shift became the foundation for the now-debated food pyramid of the 1990s, which emphasized grains as the base of a healthy diet.

In response, food manufacturers reformulated products to align with the low-fat guidance, often adding sugar and refined grains to maintain flavor and appeal—a phenomenon dubbed the “Snackwell Effect,” referring to the rise of low-fat but highly processed snack foods. These changes fueled the increased consumption of processed foods, indirectly supporting trends that some researchers now link to rising rates of obesity and diabetes.

Although the food pyramid was officially retired in 2011 and replaced by MyPlate, its legacy persists, as the broad messaging it promoted about grains, fats, and sugars continues to influence dietary habits.

“Even though it meant to encourage consumption of whole grains and small portion sizes, the pyramid’s putting grains as the foundation of a healthy diet inadvertently induced the food industry to vigorously market highly processed grain products,” Marion Nestle, a food policy expert and former DGAC member, told The Epoch Times in an email.

Carlos Monteiro, a Brazilian researcher and expert on ultra-processed foods, faulted the food pyramid for failing to differentiate between food types.

“The problem with the food pyramid is not the emphasis on grains and grain products,” Monteiro told The Epoch Times in an email. “It is the failure to distinguish whole grains from processed and ultra-processed products.”

While refined carbohydrates, such as sugars and sweets, are placed at the top to be consumed sparingly, the pyramid’s wide base for grains does not differentiate between whole and refined options. Monteiro added that this oversight extends to other categories such as meat, dairy, and fruits and persists in newer models, such as MyPlate, that also overlook food processing.

(Left) The USDA's original food pyramid, from 1992 to 2005. (Right) MyPlate guidelines launched in 2011. (Public Domain, MyPlate)

A 2015 meta-analysis highlighted foundational flaws in the guidelines, revealing that early dietary fat recommendations were implemented without evidence from randomized controlled trials.

“The guidelines were based on weak science—namely, epidemiological studies,” Teicholz told The Epoch Times. “With these studies, it’s easy to get a desired result.”

In an op-ed, she went further: “Americans aren’t growing fatter and sicker in spite of the government’s dietary guidelines but because of them.”

Ultra-Processed Foods: A Test for Kennedy

Ultra-processed foods make up nearly 60 percent of the average American’s daily calorie intake, dominating grocery shelves and diets. These include packaged snacks, sugary cereals, frozen meals, and soft drinks, many of which are made with ingredients such as high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, and artificial flavorings. While convenient and shelf-stable, they are strongly linked to obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Scientists disagree on how to define ultra-processed foods and why the distinction matters. The NOVA classification system, developed by Monteiro, is the most widely used framework for categorizing foods by the extent and purpose of their processing. It defines ultra-processed foods as those made with industrial ingredients such as hydrogenated oils, flavor enhancers, and emulsifiers designed for convenience and long shelf life. While other systems exist, no universal standard has emerged, complicating efforts to assess these foods’ health impacts.

The DGAC declined to make specific recommendations against ultra-processed foods, citing limited research.

“To set national policy, you need robust evidence,” Mattes said. “Right now, there’s only one small randomized controlled trial on this issue; it’s just not enough.”

Monteiro criticized the lack of action. “A recommendation against these foods would be beneficial for public health but detrimental to the profits of major corporations,” he said in a previous interview with The Epoch Times.

Teicholz highlighted the challenges of focusing on ultra-processed foods, calling the term “poorly defined.” She cautioned that sweeping changes, such as removing processed meats—a key protein source in school lunches—based on limited science could backfire without addressing the more pressing problems of excess sugars and refined grains.

Countries such as Brazil, France, and Israel have adopted dietary guidelines that explicitly advise reducing ultra-processed foods. Advocates view these policies as models for the United States to follow in combating diet-related chronic diseases. However, the DGAC’s cautious stance indicates the United States may lag behind in adopting similar measures.

Kennedy has signaled that he is unwilling to wait for perfect science. During his campaign, he called ultra-processed foods a major driver of the obesity epidemic and hinted at stricter regulations to come.

Ultra-processed foods make up nearly 60 percent of the average American’s daily calorie intake. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Confronting Corporate Capture

The DGAC has faced scrutiny over its ties to industry. A U.S. Right to Know (USRTK) report found that nearly half of the committee’s 2025 members reportedly have financial relationships with corporations such as Beyond Meat and Abbott. Critics argue these connections compromise the committee’s objectivity and erode public trust.

Kennedy has been vocal about addressing what he calls the “corporate capture” of federal health agencies.

“Corporate interests have hijacked the USDA’s dietary guidelines,” he said in a social media video filmed outside the USDA’s headquarters on Oct. 30.

He pledged to overhaul the system, adding, “We’re going to remove conflicts of interest from the USDA dietary panels and commissions.”

Calls for reform are not new. In 2017, the National Academy of Sciences urged stricter conflict-of-interest rules and full disclosure of committee members’ financial ties. Transparency advocates such as Sen. Chuck Grassley have since criticized the lack of progress, saying reforms have largely stalled.

“Why should Americans trust a report produced by people with so many conflicts of interest?” asked Gary Ruskin, executive director of USRTK, in a prior interview with The Epoch Times.

Do the Guidelines Work? A Mixed Report Card

The Dietary Guidelines have a broad influence but limited success in improving Americans’ diets. On average, Americans score just 58 out of 100 on the Healthy Eating Index, which measures how closely diets align with the guidelines.

“We don’t follow the dietary guidelines well at all,” Mattes said.

However, Teicholz said that Americans have largely followed the advice offered over the decades, citing government data on food consumption since 1970.

“Americans have made pretty large shifts in all food groups in the way that we’ve been advised,” she said. She also questioned the Healthy Eating Index’s accuracy, noting that it offers only snapshots in time and may overlook broader historical trends.

Although many Americans don’t follow the guidelines perfectly, the influence of the guidelines on food production, marketing, and public perception has shaped what’s widely available and affordable. Trends such as the rise of low-fat diets and increased carbohydrate consumption reflect their broader impact.

Research suggests the guidelines may not effectively improve health. The Women’s Health Initiative, an eight-year randomized controlled trial of nearly 49,000 postmenopausal women, tested a low-fat diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and grains. Despite significant cuts in fat intake, the study found no substantial reduction in heart disease, stroke, or other cardiovascular conditions. Researchers concluded that more focused strategies may be necessary to tackle chronic disease.

Another concern is systemic accountability.

“Agencies like the USDA have little accountability for the chronic diseases linked to the dietary advice they give,” Teicholz said, adding that health care systems ultimately bear the cost of poor nutrition.

Complexity also hampers the guidelines’ effectiveness. With some editions exceeding 900 pages, they can be challenging to translate into actionable advice.

“The longer the guidelines have become, the worse our health outcomes are,” Mattes said, noting that improving adherence requires practical, relatable advice.

“We can’t just issue directives and expect people to comply,” he said. “Effective change requires understanding the barriers people face and tailoring guidance to meet them where they are.”

Reform or Reinvention: The Path Forward for Kennedy

As adherence to the guidelines remains low, Kennedy’s leadership presents a rare opportunity for reform—but systemic challenges loom.

Nestle said she believes Kennedy has significant influence over the guidelines, as their finalization rests with HHS and USDA leadership.

President-elect Donald Trump has urged Robert F. Kennedy Jr., nominee for HHS secretary, to “go wild on the food.” (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

“The Secretaries appoint a joint committee to do the writing, and Congress can also weigh in,” she wrote in an email to The Epoch Times, adding that Kennedy would work with the USDA secretary to shape the direction of the guidelines.

However, Nestle cautioned that food industry lobbying and the demand for unreasonable levels of evidence have long obstructed reform efforts. She acknowledged the difficulty of relying on incomplete or evolving science to drive policy change.

Nestle admitted uncertainty about how Kennedy will approach his role.

“I have absolutely no idea what he might do if appointed,” she said, noting the slow pace and resistance often accompanying federal processes.

On whether Kennedy’s ideas align with evidence-based solutions, she offered a nuanced view. “Some are, and some are not,” she wrote. “My plan is to support the ones that have some science behind them, and oppose the ones that don’t.”

Kennedy’s exact plans for the guidelines remain unclear. His outspoken criticism of corporate influence suggests he may push for significant reform. Still, it remains to be seen whether he will work within the existing framework or chart an entirely new course.

While Kennedy’s reforms could take years to materialize, there are steps individuals can take now to improve their diets and reduce disease risk. Focusing on whole, minimally processed foods while cutting back on sugary drinks and ultra-processed snacks is a practical starting point. Small, consistent changes such as cooking more meals at home or swapping sodas for water can significantly reduce diet-related health risks.

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines may be a critical measure of Kennedy’s ability to influence federal nutrition policy. Will he succeed in reshaping federal nutrition policy and fulfilling his promise to make America healthier, or will he be constrained by the entrenched forces he seeks to challenge?

As Teicholz put it in her Substack article, “The health of our nation depends on it.”