Gabriela Bernatova collects corroded bullet casings, rusty war relics, and empty glass Coke bottles from the 1940s while scanning the mountain forests of western Czechia with her metal detector.

Last fall, she learned about an American soldier who fought during World War II after she detected a pair of lost dog tags while visiting northern Italy.

“I could clearly read the information engraved on it, including that the soldier had received a tetanus vaccination in 1946,” Bernatova, 44, told The Epoch Times. “I assume the soldier may have discarded them before leaving the area; that is only a theory.”

The avid detectorist says his name was James Steadman, reading off the letters imprinted on the worn steel plates through a patina of oxidization. The letter “A” denoted his religious affiliation—Protestant—while the designation “RA” meant “Regular Army.” He was otherwise identified as “17093719 T46 B,” the tags read.

“His service number is a unique personal identification number assigned to each enlisted soldier,” Bernatova said, adding that “T46” represents the year he was vaccinated and that “B denotes his blood type, in this case type B.”

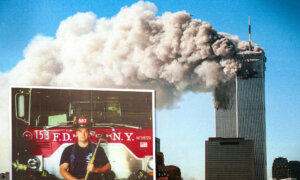

Gabriela Bernatova, who goes by the Instagram handle Detector Lady, scours WWII battlefields with her metal detector to uncover history. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

A pair of U.S. Army dog tags found in northern Italy. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

Bernatova, who works as a business consultant by day and posts her wartime finds on Instagram, became all the more curious. Gaining such intimate insights into the private life of an American soldier, now presumably long gone, she allowed her imagination to ponder the mystery.

“I want to be able to connect the image in my mind with the real face of the man who might have once thrown these tags into that pit in the corner of the garden,” she said, speaking of the 17th-century Italian estate—the villa of Count Gianni Deciani—where she gained special permission to search and excavate.

“What was his experience during his mission in northern Italy after World War II?” she wondered. “Was someone waiting for him back home?”

Lately, Bernatova has been putting out the word on Facebook and through her Instagram handle, Detector Lady, hoping to track down Steadman’s family so she might reach out and return one of the tags. The other she wants the villa to have for an exhibit in its planned new museum.

Gabriela Bernatova has found assorted coils and pins hailing from military and civilians who partook or were affected by World War II. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

Gabriela Bernatova searches a forest for detritus left from WWII. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

For Bernatova, who grew up near the Czech Republic’s western border near Germany, memories of her childhood home are filled with romps into the forests where bunkers from World War II are everywhere. “We used them as our playgrounds,” she said, recalling excursions to collect “sklíčka”—or bits of old glass or ceramic buttons, often decorated with hunting scenes or religious motifs.

“As a child, I often heard stories about hidden treasures left behind by Sudeten Germans who were expelled back to Germany after the war,” she said. “One day, while picking mushrooms, I discovered a place where there were plenty of these little treasures. From then on, I spent almost every weekend in the forest searching for these glass glass ‘gems.’”

The Sudetenland was a predominantly ethnic German part of Czechia where Hitler’s army initiated his second expansion (after annexing Austria) before many subsequent invasions throughout the war, though it’s now become a play place for children. It’s also filled with small wartime artifacts that have spurred adventurers, like Bernatova, to take up metal detecting.

(Left) Coke bottles left over from WWII; (Right) A U.S. soldier's button. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

She'd heard word “metal detector” as a young girl though it faded from her mind for years, until the COVID-19 pandemic happened. Bernatova, a mom by now, was desperate to breathe the fresh air of the mountains again. The metal detector she ended up using was originally a Christmas present for her kids (which they ignored in favor of novels). She’s been detecting ever since then.

“I completely fell in love with this hobby,” she said.

Now, when she isn’t busy on business trips across Europe and to Asia—where she helps clients in the manufacturing industry to expand their sales on Amazon—she is collecting the occasional “SS” pin and war-era dagger as her pastime. She’s found countless crucifixes and military badges.

World War II-era objects found by Bernatova include U.S. Army buttons and ordinary objects like toothbrushes. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

Gabriela Bernatova gets to work with her metal detector. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

“This kind of work gives me the freedom to travel and also to pursue my passion, which is history,” she said. “I love studying our history, collecting old coins, exploring places with a metal detector, and uncovering the stories and fascinating places.”

After a stint metal detecting on the beaches of Vietnam last year, Bernatova visited northern Italy and had the good fortune of connecting with a former employee of the Villa Gallici Deciani last fall. It had been occupied by the Germans before American troops gained control near the war’s end. The Italian resistance, or la Resistenza, had also waged a campaign of sabotage against the German Wehrmacht while a countess from the estate was a resistance sympathizer.

A military document attests that the 350th Infantry served at the villa of Count Gianni Deciani. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

War-era relics found at the Villa Gallici Deciani in northern Italy. (Courtesy of Gabriela Bernatova)

“Because of the villa’s unique connection to occupation, resistance, and postwar recovery—and to Countess Giulia’s extraordinary role—the site is filled with layers of history,” Bernatova said, adding that she spent days uncovering memorabilia and eventually found the American soldier’s dog tags in a corner of the garden.

“I also found numerous Coca-Cola bottles dated 1944 and 1945,“ she said, ”along with old beer bottles and many personal items such as toothbrushes, empty toothpaste tubes, razor blade boxes, and other everyday objects.”

Through scouring historical records she has learned about a U.S. Army division that was stationed at the estate at that time, though she admits there’s no guarantee Steadman served among its units. After the war, a veteran from the 350th Infantry, as part of 88th Division, did return to the estate where he was stationed and presented a book documenting the infantry’s service.

So far, though, Bernatova’s efforts to locate James Steadman’s surviving family have been unsuccessful, despite her network of international contacts. They’ve found no official records that match his service number. It’s possible, she says, that old U.S. Army documents are routinely destroyed and that his records may no longer exist.

“However, I’m not giving up,” she said. “I truly hope that by continuing to share this story, someone who reads or sees it might recognize the name James Steadman and contact me with any information that could help reconnect his memory with his family.”