The day after the twin towers fell, John Huvane drove through the tunnel to Manhattan and saw the endless white smoke that permeated the island. Huvane, then a New York City detective who'd just turned 40, stopped his car and asked himself, “Where are you going? You just got out of this.” Then Huvane did what the hundreds of thousands of fellow first responders did in the weeks and months of recovery efforts that followed 9/11.

He drove to work.

Every day for about four months, Huvane survived at ground zero on adrenaline and the heightened awareness it imbues on the miraculous human body as he and countless other rescuers worked like ants upon an incredible heap of 1.6 million tons of pulverized concrete. Along with exposure to toxic concrete carcinogens, they experienced jet fuel-laced air, glass, and asbestos entering their lungs.

But permeating all this, Huvane told The Epoch Times, “there was such a heavy smell of death.”

A firefighter prays after the World Trade Center buildings collapsed on Sept. 11, 2001. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Huvane, who has been through three shootings in his career and terror attacks in London and Mumbai, says that all else pales in comparison with his experiences during Sept. 11 and the recovery efforts that followed. Yet today—as he joins firefighters on stair climbs, as he supports families of first responders on 5K runs to help the catastrophically injured, and as the organization he now co-presides over, Tunnel to Towers, will have paid off over 200 home mortgages this year for families who lost loved ones to 9/11 recovery health hazards—Huvane says the attacks haven’t shaken his optimism.

“No, I see good people, and I see amazing sacrifices and acts of bravery,” he says. “It’s so inspiring.”

One of Huvane’s many inspirations is a firefighter who died in the twin towers disaster when he could have been playing golf. While Huvane drove to work the day after the attacks, Stephen Siller had just gotten off a shift right before them. He was about to hit the fairways with his brothers in Brooklyn when he heard the scanner in his truck crackle and learned that a plane had crashed. Driving back to the station, he grabbed 60 pounds of gear and oxygen and headed for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel.

Ominously, Siller found that it was closed. He would have to hike the tunnel under the East River.

Moments before the attacks, in Manhattan, Huvane was on duty as a mayor’s bodyguard. He was later at the scene of the twin towers after they were hit but before they had fallen. “We were at a breakfast in midtown Manhattan, and we got a call that a small plane had hit the tower,” he told the newspaper. “I jumped ahead to go down there.”

What he saw was uncanny.

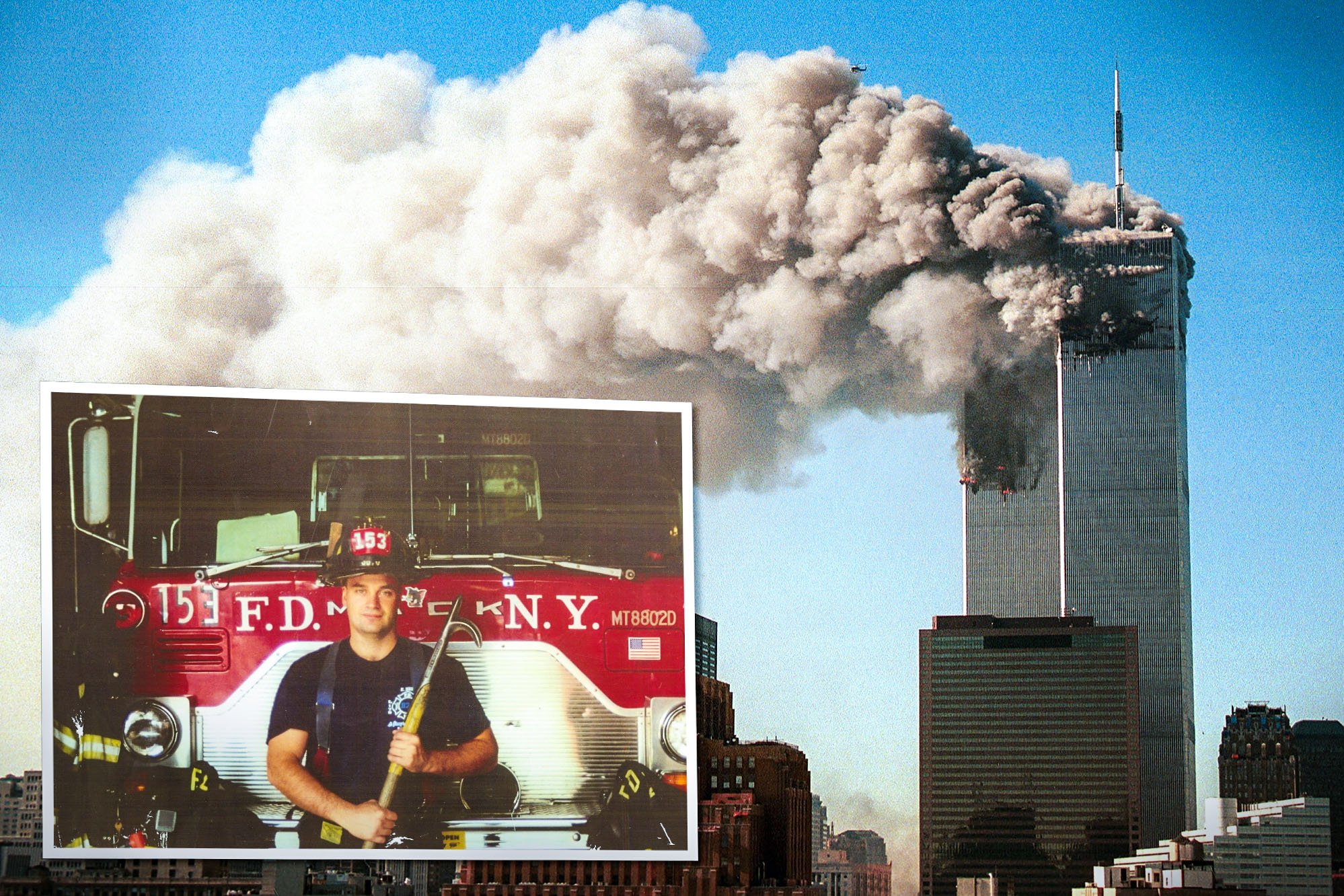

Smoke pours from the twin towers of the World Trade Center after they were hit by two airliners in a terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001, in New York City. (Robert Giroux/Getty Images)

“Chaotic is not the word,” he said. “There were people who were running from the building. Women were dropping their bags and taking off their shoes and running in their bare feet. I walked right by an engine of a plane.” Huvane would not forget the sight of people jumping from the building, nor the sound a human body makes when it hits the ground. He saw pieces of building and plane falling and heard horrific noise all around.

As the city government tried to reestablish control as best it could and get military support, the bridges, tunnels, and everything else that needed to be shut down all was shut down. The country was under attack, and no one knew whether there would be more attacks to come.

Policemen and firemen run away from the huge dust cloud caused by the World Trade Center's Tower One collapse after terrorists crashed two planes into the twin towers on Sept. 11, 2001, in New York City. (Jose Jimenez/Primera Hora/Getty Images)

It was “very dangerous,” Huvane said, as people and debris were falling, and “you don’t want to be underneath when they landed.”

Huvane was speaking to a motorist when suddenly the driver put the vehicle into reverse and hit the gas. The motorist had seen what Huvane could not see, as he was faced in the opposite direction, until he turned around: The first of the two towers to come down came down in a rolling plume of white smoke. It rolled between the buildings on either side of the street toward him.

“It looked like that scene in Indiana Jones where the big ball is coming towards you, and you start running from it,” Huvane said. “So I started to run from it, and it was catching up to me. So I made a turn on one of the side streets.”

He narrowly escaped but could feel the sheer power of the blast.

And when he saw a fire truck heading up the side street towards him and towards the twin towers, he tried to flag them away. “I don’t know what fire truck that was, and I don’t know if those firefighters died that day,” Huvane said.

Stephen Siller. (Courtesy of <a href="https://t2t.org/">Tunnel to Towers</a>)

Huvane says that after the second tower came down, after he jumped onto the mayor to shield him, and after a small headquarters for dealing with the crisis was finally established, he was fortunate enough to go home that evening, unlike dozens of his friends. Unlike Siller—who descended into the hot and muggy Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and lugged his heavy gear for nearly 3 miles to join his fellow firefighters, never to return—Huvane drove to work the next day and began the horrific recovery efforts.

“I probably know 50 guys that died that day, another 20, 25 that died since,” he said. He didn’t know Siller but came to learn of his sacrifice and how the organization Tunnel to Towers was founded by his brother Frank Siller in his honor. “He was off-duty,” Huvane told the newspaper. “He could have easily gone and played golf. But these first responders, these firemen, they were coming in, all off-duty.”

This year, Huvane, now 63, and Frank Siller are honoring first responders from the recovery efforts who have died from the long-term health impacts. Tunnel to Towers will pay off the mortgages and cover mental health services for hundreds of surviving families. Rodrick Covington, a New York State Police major who died of an aggressive cancer in March 2022, was among them. “I got to know him on a professional level,” Huvane said, speaking of their time serving the city together.

“True heroes are the ones who are left behind. Obviously not to diminish the heroic acts that these people performed, but to get up every morning after you lose your loved one,” he added, “is something heroic in itself.”

Share your stories with us at emg.inspired@epochtimes.nyc, and continue to get your daily dose of inspiration by signing up for the Inspired newsletter at TheEpochTimes.com/newsletter.