Independence Day is the nation’s most patriotic holiday, and Americans celebrate it with abandon.

On this day of parades, baseball games, hot dogs, and sparklers, even the stodgiest old uncle may arrive at the family cookout wearing a red, white, and blue top hat and suspenders.

By day’s end, about 260 million pounds of commercial fireworks will be lit, filling city skies with splendor and leaving the air in suburban neighborhoods thick with the smell of smoke and sulfur.

Americans love to display their patriotism.

Yet there is little agreement on what that means. The majority—about 55 percent—of Americans think the United States has become a less patriotic nation in recent years, according to a Marist poll released on July 1. Only 14 percent think Americans have become more patriotic.

That could be because Americans display patriotism in a variety of ways and may not recognize it in others, Ken Kollman, director of the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan, said.

“Definitions of patriotism, and behavioral standards for what counts as patriotic, are both folded into our current political divisions and reflect them,” Mr. Kollman told The Epoch Times. “Who counts as a patriot and what counts as patriotism are in the eyes of the beholders.”

Just ahead of the 248th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, The Epoch Times asked Americans to define patriotism.

“What does patriotism mean to you?” we wanted to know, “and how do you display it?”

Most answers were rooted in a deep appreciation for sacrifices that were made to create and defend the country, and a desire to continue to do the same. That desire manifests itself in different ways.

Honoring the Symbols

Pride in the United States and its symbols was the most common way that people said they expressed patriotism. We heard frequent references to standing for the national anthem, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and wearing star-spangled clothing. Voting was mentioned often.

These simple expressions of national pride can also be used by some—though not by everyone—to emphasize divisions within the country, according to John Bodnar, emeritus professor of history at Indiana University.

Locals take part in the annual Fourth of July Bicycle Cruise in Huntington Beach, Calif., on July 1, 2023. A majority of Americans (55 percent) think the United States has become a less patriotic nation than it was a few years ago. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

“Some people express their patriotic loyalty to show they are superior to other citizens within the nation,” Mr. Bodnar told The Epoch Times. “On the other hand, some patriots see in the flag or in the nation they love the promise of equal rights for all, regardless of one’s political views or race or religion.”

The latter seemed to describe most of the people whom we encountered.

Bailey, 31, of Las Vegas, said that standing for the national anthem is one way that he shows patriotism. Another was his recent visit to the nation’s capital. He believes that a patriot should respect the office of the president regardless of which party is in power.

“You love America? You’ve got to love who’s running it,” he said.

Healing Divisions

Brothers Peter and Rory Corrigan, whose parents met while serving their country during World War II, are driven to both honor the past and ensure that the United States lives up to its promise.

Their father, a lieutenant in the Marine Corps’ Seabees battalion, met their mother on Guam, where she served with the Red Cross.

“[Our father] rarely talked about the war. Both parents had acquaintances who were killed or seriously wounded in the Pacific,” Peter Corrigan, 76, of Delmar, New York, told The Epoch Times.

Yet the war symbolized something more than bloodshed to the elder Corrigan brother.

“One night in the mid-1950s, while tucking me into bed, I was probably 7 or 8, [my father] asked if I could think of one good thing about the war,” Mr. Peter Corrigan recalled. “I tried, but I couldn’t.”

What his father said next made a lasting impression on the boy.

“It’s where I met your mother,” he said simply.

Mr. Peter Corrigan now honors the sacrifices of the Greatest Generation by wearing a Seabees cap and holding an American flag as veterans pass by in the Memorial Day parade.

“And I think how grateful I am to live in this country,” he said.

Brother Rory Corrigan, 74, of Richmond Hill, Georgia, said his sense of patriotism took on a more profound meaning after the 9/11 attacks.

“I lost 37 friends that day,” he said. “My sense of America’s unique promise and necessary leadership was deepened as the face of evil confronted me in a new and profound manner.

“I have never been prouder of our country than in the period closely following those attacks,“ Mr. Rory Corrigan said, citing pride in the nation’s struggles ”to overcome our demanding history and divisions.”

(Top) A parachutist brings in the U.S. flag before the start of the 101st annual Black Hills Roundup rodeo in Belle Fourche, S.D., on July 4, 2020. The town celebrated Independence Day with the rodeo, a parade, a street dance, and a carnival. (Bottom) Guests remove their hats during a salute to veterans before the start of the rodeo. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Connecting America to the World

Peter McCormick, 69, of Dunedin, Florida, found a sense of patriotism as a foreign correspondent in Central America during the 1980s.

“It was our backyard, and as a reporter I realized U.S. readers needed, as citizens, to know what was going on,” he told The Epoch Times.

Mr. McCormick said his reporting on Marxist versus right-wing factions shattered preconceived notions held by friends on both the left and the right.

He later worked as a U.S. Agency for International Development contractor in Rwanda, where he wrote checks to charities that supplied wells, food, and medical attention to that war-stricken nation. Mr. McCormick considered it an expression of patriotism.

“The operation was an example of American largesse being put to efficient use,” he said.

Political Activism

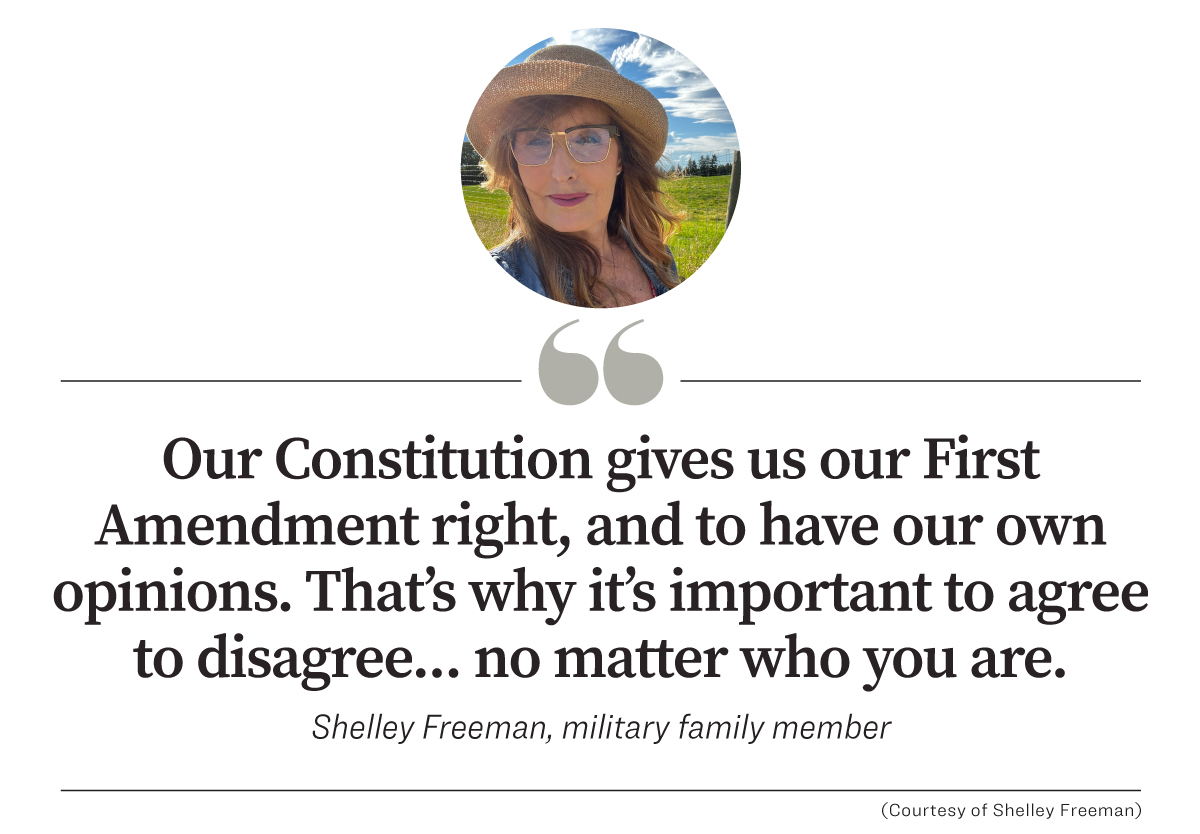

Shelley Freeman, 58, of Clements, California, is part of a four-generation military family and has a son now on deployment with the Army. She has served her country as a civilian by sitting on local government committees, volunteering for Senate and presidential campaigns, and hosting political discussions on social media.

She sees political discourse as unifying rather than divisive.

Ms. Freeman recalled a discussion she had about presidential candidates that provoked strong disagreement from another woman. Although the debate was intense, it ended with a hug.

“It’s OK. We’re going to get through this, and we’re all going to be alright,” Ms. Freeman said she told the debater.

“Our Constitution gives us our First Amendment right, and to have our own opinions,” she said. “That’s why it’s important to agree to disagree ... no matter who you are.”

Dissent

Rachel Taillon, 31, at her home in Lake Butler, Fla. (Courtesy of Rachel Tallion)

Patriotism required a change in lifestyle for Rachel Taillon, 31, of Lake Butler, Florida, who relocated with her family from another state. The move was motivated by a desire to live their version of the American dream, free from what they saw as government intrusion.

“We decided to take a stand against our government’s new policies and pick up everything we own and our entire life and move,” she told The Epoch Times.

With her husband, Brendan, and four young children, Ms. Rachel Taillon now homesteads on rural land, homeschools, raises farm animals, and works diligently to create a self-sustaining life.

Patriotism is often rooted in disobedience to government actions gone wrong, she said.

A person watches the fireworks show on the Hudson River, behind the Empire State Building that is lit up in red, white, and blue, in New York City on July 4, 2023. (Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

Defending Constitutional Rights

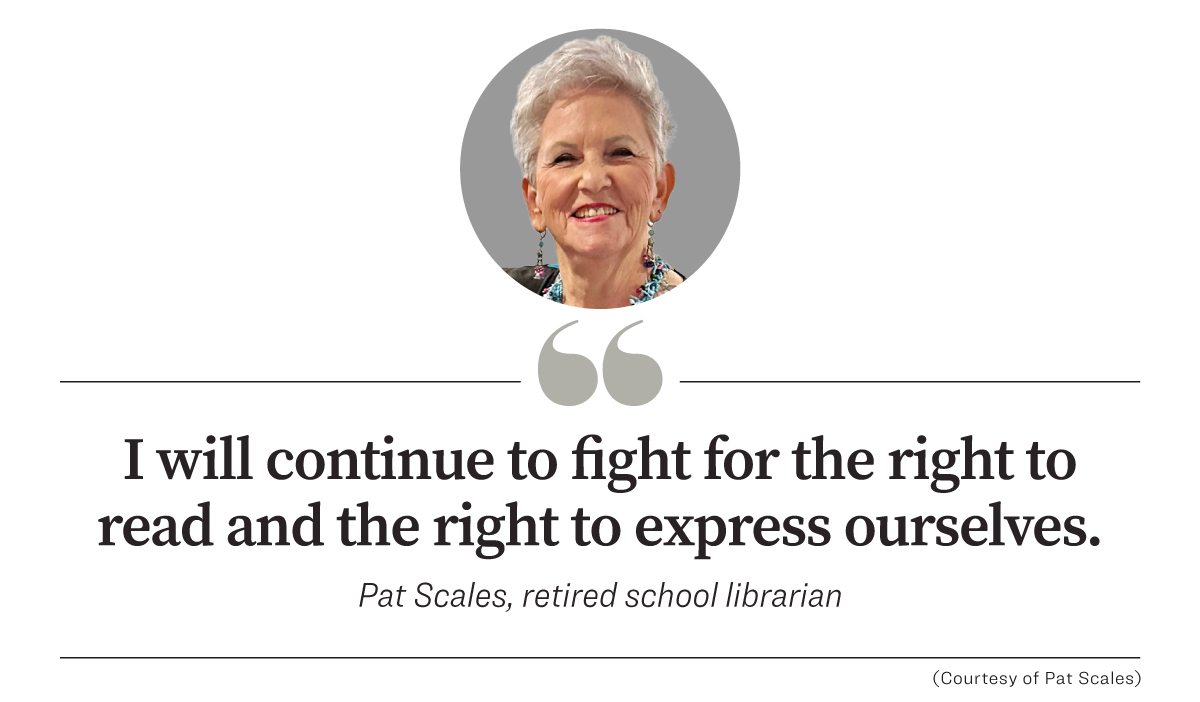

Patriotism springs from an appreciation for the Founding Fathers’ long struggle to create a democratic government, according to Pat Scales, 79, of Greenville, South Carolina.

Ms. Scales, a retired middle and high school librarian, said she expresses patriotism by speaking to politicians and school boards about freedom of speech and helping others to stand up for their rights as citizens.

Brian Dietz, 72, an Army veteran from Venice, Fla. (Courtesy of Brian Dietz)

“The main thing I do is defend the freedoms that were outlined to us in the First Amendment of the Constitution,” she told The Epoch Times. “I will continue to fight for the right to read and the right to express ourselves.”

Brian Dietz, 72, an Army veteran from Venice, Florida, is an advocate for First and Second Amendment rights.

“I don’t think there are many people at all that actually know the importance of the U.S. Constitution or how this country was founded,” he said. However, Mr. Dietz is filled with hope that Americans can fix the problems that they face.

Respect for the Privilege

For most of the people whom The Epoch Times interviewed, patriotism goes beyond appreciating the United States’ bounty and freedom. It extends to respecting the ideas and values that motivated previous generations to make sacrifices to create and defend the Republic. And that implies taking seriously the responsibility attached to citizenship.

“Patriotism to me means to hold the privilege of being an American in high regard,” Kailas Chong-You, 21, of Newberry, Florida, said.

“Patriotism to me doesn’t just mean to have an American flag in my room. But to also have a healthy concern for the country that I live in,” the grandson of immigrants told The Epoch Times.

“Being able to live in America and call the country my nation means a lot to me.”