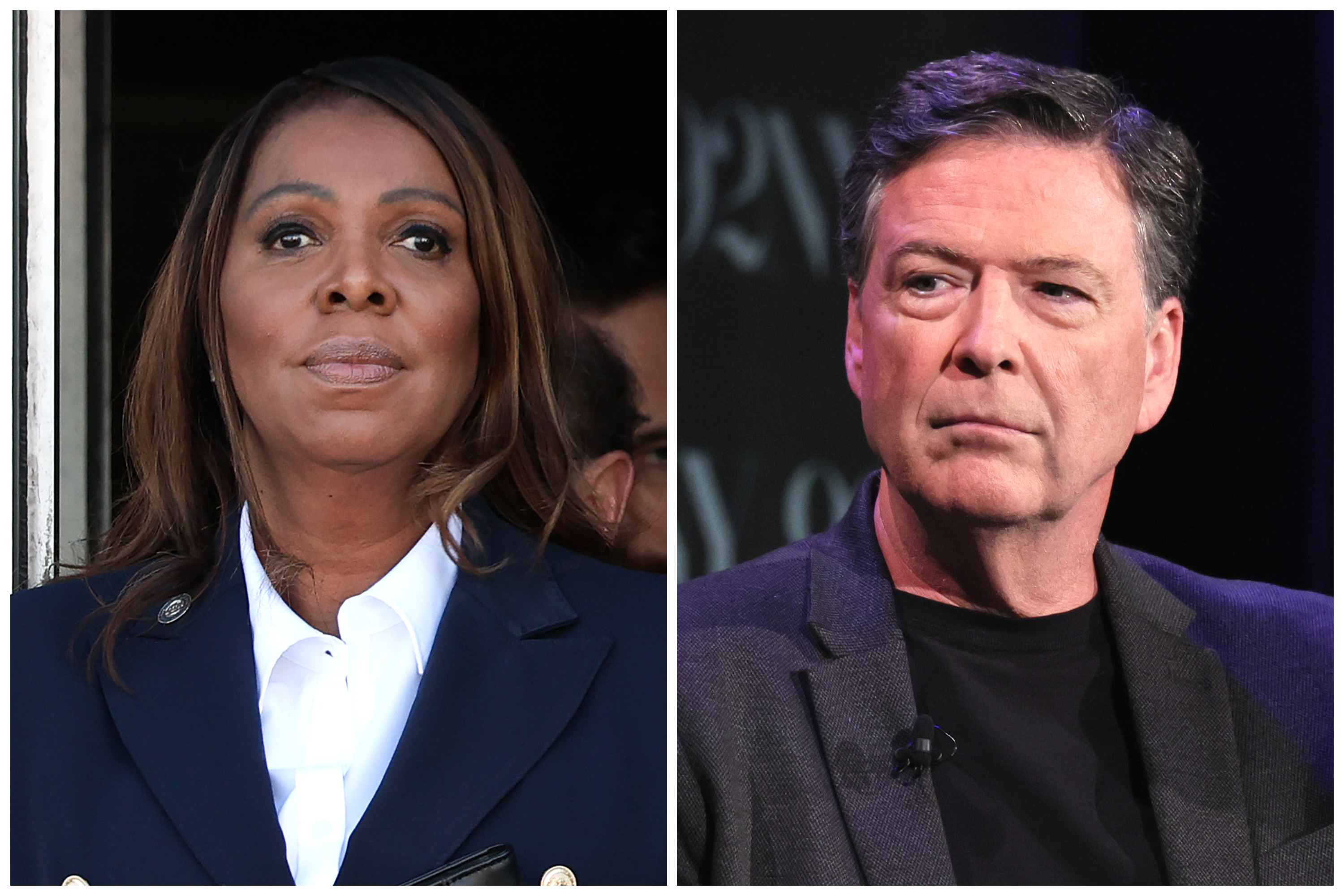

A federal judge has dismissed the Justice Department’s cases against former FBI Director James Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James, throwing a wrench in the prosecutions and teeing up potential legal battles over attorney appointments.

In an opinion on Nov. 24, U.S. District Judge Cameron McGowan Currie said the Justice Department unlawfully appointed Lindsey Halligan, who brought both cases, as the interim U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Here are some takeaways from her decision and what it means for the cases.

1. Judge Says 120-Day Limit Exists for Attorney Appointments

Currie’s

decisions centered on a law Congress passed governing how the Justice Department could fill vacant U.S. attorney spots. Under 28 U.S.C. Section 546, federal law allows interim attorneys to serve for 120 days, further providing that district courts “may appoint” a U.S. attorney to fill vacancies at the end of that timeframe if the Senate hasn’t already appointed a replacement.

The Justice Department had argued the law didn’t confine the attorney general to an initial 120 days for appointing prosecutors. Rather, the department stated, the law allowed for successive appointments of attorneys who would each have 120-day limits on their time in office.

Currie disagreed and said on Nov. 24 that the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia had the power to appoint a replacement for Erik Siebert, Halligan’s predecessor.

“In sum, the text, structure, and history of section 546 point to one conclusion: the Attorney General’s authority to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney lasts for a total of 120 days from the date she first invokes section 546 after the departure of a Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney,” she said.

“If the position remains vacant at the end of the 120-day period, the exclusive authority to make further interim appointments under the statute shifts to the district court, where it remains until the President’s nominee is confirmed by the Senate.”

2. Dismissed ‘Without Prejudice’

While Currie granted Comey’s and James’s requests to dismiss their cases, she did so without prejudice. That typically means that the indictments can be replaced with new ones if brought under the right circumstances.

Former federal prosecutor Neama Rahmani told The Epoch Times that the Justice Department could easily bring a new case against James, but that Comey’s case was over, pending appeal. Halligan had sought Comey’s indictment just days before the statute of limitations expired in his case, meaning that the administration’s limited timeframe for indicting has likely passed.

The indictment focused on statements Comey made to Congress on Sept. 30, 2020, and cited a federal law that has a five-year statute of limitations. If an indictment is brought before the statute of limitations expires, it “tolls” or stops the clock on the charges.

However, Currie indicated in a footnote that Comey’s indictment couldn’t be brought again because Halligan’s involvement made it invalid. She said that while valid indictments typically toll the statute of limitations, “there is no legitimate peg on which to hang such a judicial limitations-tolling result” with a void indictment.

3. Judge Says Bondi’s Ratification Too Late

The Justice Department did not respond to The Epoch Times’ request for comment before publication, but a top official remained hopeful following Currie’s ruling.

On social media, U.S. Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division Harmeet Dhillon emphasized the nature of the ruling.

“WITHOUT PREJUDICE,” she said. She also reposted Ed Whelan, a legal scholar with the Ethics and Public Policy Center, suggesting that another indictment could be brought against Comey. He pointed to 18 U.S.C. Section 3288, which states that new indictments can be brought within six months of an appeal.

That law specifies that it doesn’t allow a new indictment to be filed “where the reason for the dismissal was the failure to file the indictment or information within the period prescribed by the applicable statute of limitations.”

Although Currie’s opinion focused on the validity of Halligan’s appointment, she also stated that the indictment itself was still pending as of Oct. 31. That’s the day that Bondi identified in a declaration as the day she had ratified the indictment.

Justice Department attorneys had argued that even if Halligan’s appointment were invalid, the indictment itself shouldn’t be dismissed because it was ratified by Bondi. Currie, however, rejected that argument and said that the Oct. 31 ratification came weeks after the statute of limitations had expired.

4. Appeal Coming

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said on Nov. 24 that the administration would appeal the decisions, which could prompt a higher court ruling on Section 546 or attorney appointments more generally.

Currie’s decisions were relatively limited in their impact as they applied only to Comey’s and James’s cases.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit is considering whether Alina Habba, who represented Trump in his New York business fraud case, was validly serving as an acting U.S. attorney for the District of New Jersey. If appealed, Currie’s decision would be under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

Like Halligan, Habba initially received a temporary appointment as U.S. attorney but was later named a “special attorney.” Habba’s case is a bit different, however, in that she was subsequently named an assistant U.S. attorney in New Jersey and became the acting U.S. attorney after the administration fired the person above her.

The Justice Department has argued that Halligan “at least was a de facto officer, and any error was harmless since the Attorney General indisputably could have appointed her in a different capacity to obtain the indictments.”

Currie said that regardless of Bondi’s Oct. 31 appointment, Halligan was not a valid Justice Department attorney when she sought the indictments against Comey and James.

“The implications of a contrary conclusion are extraordinary,” the judge said. “It would mean the Government could send any private citizen off the street—attorney or not—into the grand jury room to secure an indictment so long as the Attorney General gives her approval after the fact.”

5. Long Road Ahead

Assuming the Justice Department wins its appeal, which could take months, it’s expected to face additional hurdles before bringing either Comey or James to trial.

Both defendants have brought motions to dismiss based on the idea that the Justice Department was vindictively targeting President Donald Trump’s political enemies.

Comey’s case is more complicated than James’s. He has filed multiple motions to dismiss, while judges have also raised concerns about how grand jury proceedings unfolded. Besides alleging that the indictment was based on fundamentally ambiguous language, Comey has also argued that the case lacks a valid indictment. The Justice Department has denied that argument, but the filing could nonetheless add to mounting pre-trial litigation, including over potential discovery.

Before Comey’s case was dismissed, a magistrate judge had also ordered the disclosure of grand jury materials to the defense. Acknowledging the order was “extraordinary,” U.S. Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick said it was necessary to protect Comey’s rights and that the government engaged in “a disturbing pattern of profound investigative missteps.”

That order has been temporarily stayed by another federal judge overseeing the case.