In 1896, a journalist for the San Francisco Call reported that keepers at California’s Pigeon Point Lighthouse were perplexed. Visitors often made repeat visits up the tower’s spiral staircase to view the lamp.

“This is a mystery to the keepers,” wrote the journalist, “who fail to see what the visitors can find to interest them after they have been there once.”

Clearly, these particular keepers did not understand the lasting allure lighthouses have for the public.

Pigeon Point Lighthouse’s spiral stairs in 2007. (Courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard and National Archives)

In general, lighthouse tourists can be broken down into three different types: the casual fan, the enthusiast, and the “lighthouse junkie” who makes every effort to visit lighthouses far and wide.

No matter the type, most people can’t help but view a lighthouse through a romantic prism. Where else does hope glow so brightly as from a beam of light shining across a dark sea? Mariners who remain offshore for months at a time would likely agree.

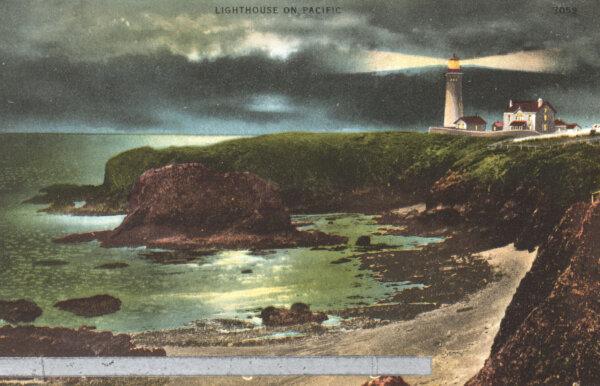

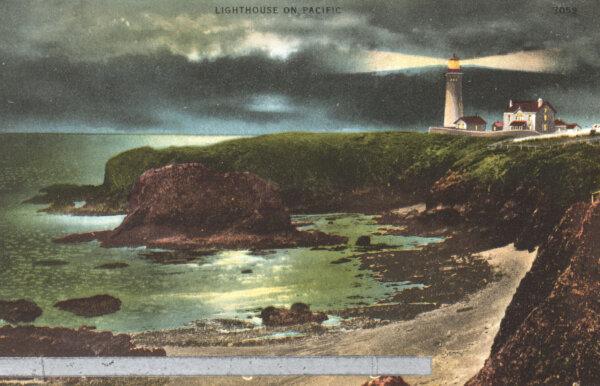

Light shines from Pigeon Point Lighthouse on a 1907–1915 postcard. (Courtesy of the Herb Entwistle Postcard Collection, National Archives)

Keepers may have had a more pragmatic view of lighthouses. In their eyes, the purpose of a lighthouse was to provide a reference point for seamen, to warn ships off of dangerous shores, or to light up safe passages to port.

Pigeon Point Lighthouse was built to act as a navigational reference point and to alert mariners to a treacherous stretch of California’s San Mateo coast.

A view of the Pacific Ocean from Pigeon Point on California’s San Mateo coast. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

How Pigeon Point Lighthouse Came to Be

On the morning of June 6, 1853, a thick fog settled along the San Mateo coast of California. The Carrier Pigeon, a clipper ship from Boston, sailed north toward San Francisco. Halfway between Santa Cruz and what is now known as Half Moon Bay, she ran aground and began to break up against the rocks.

The crew made it to shore safely, and ships dispatched from San Francisco salvaged some of the cargo. Ultimately, however, the ocean destroyed the Carrier Pigeon, resulting in a huge financial loss to investors, insurance companies, and merchants.

As a result of the shipwreck, the federal government decided that fog signals and a lighthouse were needed along that area of coastline. The exact location would be chosen by the U.S. Coast Survey team. They chose a cliff 500 feet from where the Carrier Pigeon had struck.

Named Punta de las Balenas (Point of the Whales) by the Spanish, it was renamed Pigeon Point after the wreck of the Carrier Pigeon.

Looking south from Pigeon Point along the San Mateo Coast of California. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Unfortunately, it took another 19 years for the lighthouse to be built. In the meantime, three more wrecks occurred near Pigeon Point, with great loss of life. Media exposure and public outcry prompted the federal government to finish the job.

First they completed the fog-signal system on Sept. 10, 1871, then the lighthouse. On Nov. 15, 1872, a keeper lit the oil lamp inside the lens of the lantern room, and rays of light shone out from Pigeon Point Lighthouse.

How Did a 19th-Century Lighthouse Work?

Lighthouses in the 19th century had a lantern room at the top of a tower. Inside the lantern room was a lens, typically a Fresnel lens (pronounced fra-nel). Inside the lens was an oil lamp. When the lamp was lit, light beams shone through the lens.

The Fresnel lens—made up of many smaller prisms and lenses—bent and focused the light far out to sea, where it could be seen by passing ships.

To help with identification by day, each lighthouse had distinguishing features. These included the height and width of the tower, its architectural style, and its painted patterns and colors—known as daymarks.

For night identification, each lighthouse had specific lighting characteristics, such as a fixed light or a revolving light. Revolving lights “flash” at timed intervals. The lights can be white, green, or red, or a combination thereof. These characteristics are also known as the lighthouse signature.

Pigeon Point Lighthouse has a 10-second signature, meaning a white light “flashes” (revolves into view) every 10 seconds.

A model of Pigeon Point lighthouse and oil house on display in the fog-signal building. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Inactivated foghorns (diaphone horns) protrude from the back wall of Pigeon Point’s fog-signal building. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Pigeon Point Lighthouse Today

Pigeon Point Lighthouse has a 115-foot-tall tower. Until 1972, light shone through a first-order Fresnel lens that was six feet wide and seventeen feet high; then the lighting was changed. A 24-inch rotating aero-beacon was mounted on a railing outside the lantern room. It kept the same 10-second signature.

In 2001, damage to the upper part of the tower caused the lighthouse to be closed. However, the grounds, fog-signal building, and hostel remained open to visitors.

In 2024, restoration work began on the lighthouse tower and oil house. It is hoped that work will be completed by the end of 2025.

Pigeon Point Lighthouse is undergoing restoration in 2024. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

The Future of Pigeon Point’s Fresnel Lens

Though signage states that the Fresnel lens will one day be returned to the top of Pigeon Point’s lantern room, this is actually in question. Currently, the state government is considering leaving the original Fresnel lens in the fog-signal building, in order to make it ADA compliant (physically accessible).

However, the state also has the option of displaying a smaller lens in the fog-signal building, which would allow the original lens to be reinstalled in the lighthouse.

Even if the Fresnel lens is returned to the lantern room, it will only shine on special occasions. This is because the light is extremely bright, shining as much as 22 miles out to sea. This poses a danger to migrating birds.

However, the U.S. Coast Guard does plan to install an automated light that is less bright. It will keep Pigeon Point’s 10-second lighting characteristic.

Restoration experts from ICC Commonwealth show their enthusiasm from the top of the lighthouse tower. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Visiting Pigeon Point Lighthouse

Although scaffolding covers the lighthouse tower at this time, it’s still worthwhile to visit Pigeon Point Lighthouse. To begin with, the first-order Fresnel lens is on display in the fog-signal building. With its 1,008 separate lenses and prisms, including 24 “bullseye” flash panels, the Fresnel lens is a beautiful sight.

The first-order Fresnel lens is displayed inside the fog-signal building at Pigeon Point Lighthouse. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Secondly, visitors can learn much from docents who share their knowledge about the lighthouse, area history, and wildlife. There are also many informative signs and displays inside the fog-signal building.

Finally, Pigeon Point itself is beautiful. From the cliffs, visitors have an unobstructed view of the Pacific Ocean. Harbor seals lounge on the rocks below. Seabirds fly nearby, and whales can sometimes be seen off the coast. Next to Pigeon Point, there is also the enticing Whaler’s Cove, where rum-runners used to smuggle whiskey in from Canada.

Harbor seals lounge on rocks below Pigeon Point Lighthouse. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Whaler’s Cove is located next to Pigeon Point on the San Mateo Coast. (Courtesy of Karen Gough)

Hours and Location

The Pigeon Point Light Station State Historic Park is located at 210 Pigeon Point Road, Highway 1, Pescadero, CA 94060.

The day-use area is open from 8 a.m. to sunset.

The visitor center and gift store is open Friday to Monday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Docent-led tours of the grounds take place on Sundays at 2 p.m. See their website (parks.ca.gov) for more information, or call 650-879-2120.