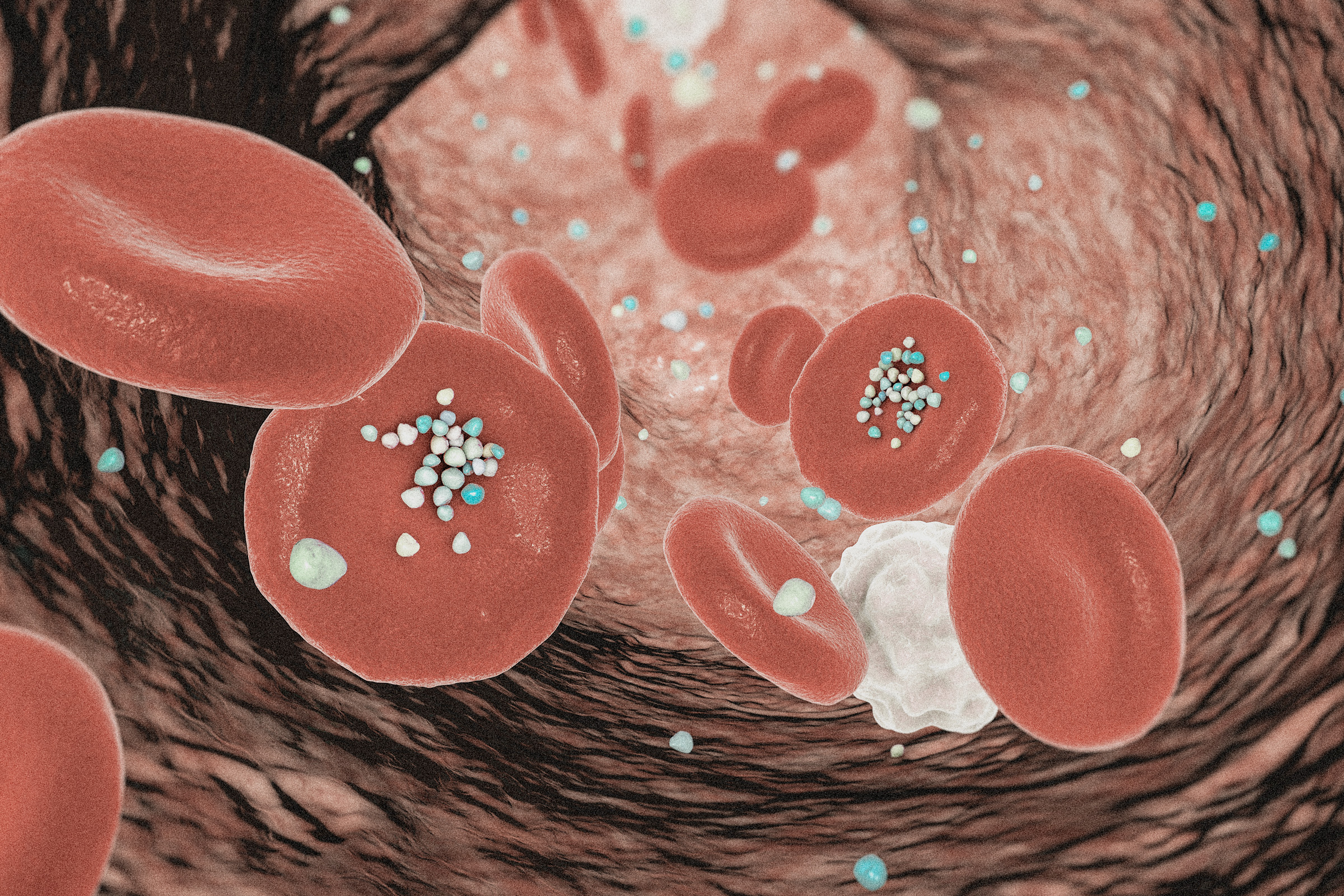

As scientists sound the alarm over microplastics in human brains—which may be as much as a plastic spoon’s worth—some people are turning to at-home tests to measure how much plastic is in their bloodstream.

These kits offer a snapshot of microplastic concentrations, along with personalized “battle plans” with actionable steps for reducing exposure.

But as interest in these at-home tests grows, experts caution that they are likely to deliver more anxiety than answers.

The Caveat With Blood Tests

While blood may seem like an obvious starting point, since it’s the highway through which substances travel to various organs, it may not be the most reliable way to detect microplastics, Dr. Matthew Campen, head of the toxicology laboratory at the University of New Mexico, told The Epoch Times.

Campen compares blood to a city’s metro system: millions of people live in the city, but only a small fraction will be on the train at any given time. The levels of microplastic in the blood is also transient.

Since blood is essentially just a “transit route” for these particles, the concentrations found in blood could be far lower than in organs where they might settle, Campen said.

Campen’s team has detected more than 5,000 micrograms of plastic particles per milliliter of brain tissue, while a 2022 study in organ donors have estimated around 1.6 micrograms per milliliter of blood.

Given this, testing for microplastics in blood could be highly misleading.

Dr. Win Cowger, research director at the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research, agrees. “The combination of limited quantities in the blood and the challenges of sampling means the results from these tests are highly uncertain,” he told The Epoch Times.

Detecting Plastic in Blood Is Difficult

With just a finger prick of blood, manufacturers of these at-home tests say that they screen for common plastics found in products like toys, cosmetics, and beverage bottles—such as polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

“A drop of blood is a very small unit,” Cowger explains. Current studies estimate there are only around four microplastic particles per milliliter of blood, while a single drop of blood is far smaller at just one-tenth of that.

Getting a reliable estimate of microplastics in circulation is therefore challenging since a single drop of blood will give a smaller sampling of microplastics.

“You have about a 40 percent chance of finding just one [microplastic] particle,” Cowger said. This makes detection especially difficult when using home testing methods.

“Most of these [at-home] tests will use a spectroscopy based technique which can only detect particles greater than say 20 micrometers in size,” Dr. Cassandra Rauert, a research fellow at the Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences in Australia, suggested to The Epoch Times in an email.

“Particles this size are very unlikely to end up in the bloodstream,” she adds, “as they can’t pass through biological barriers in the body.” Instead, these larger particles, whether ingested or inhaled, remain in the gastrointestinal tract or lungs, respectively, as they are too large to enter the bloodstream.

Rauert, who investigates human exposure to microplastics and develops detection methods, co-led a January 2025 study showing that even with advanced equipment, it is harder to detect plastics like PE and PVC in human blood than purified water—up to 20 times harder.

While water is a single substance, blood is a complex mixture of cells, proteins, and other substances that make it harder to detect microplastics, even when present at higher concentrations.

Contamination and False Positives: A Double Whammy

Contamination is another concern of at-home testing. Microplastics are everywhere—found in the air we breathe, the products we use, and even in the equipment used for testing. Outside of controlled lab environments, such as with at-home kits, blood samples are vulnerable to picking up microplastics from the surrounding environment.

“It is very easy for them [particles] to fall into the blood sample and contaminate it,” says Rauert. “There are no control measures in place [at people’s homes] to account for this with these tests.”

A 2021 study examining 20 homes over six months found that indoor microplastic concentrations were as much as 45 times higher than outdoor levels.

“There is always a chance with any measurement that you have contamination from the air or the sampling device getting into the sample,” says Cowger, explaining how this can lead to overestimations of microplastics in blood.

“Any contamination of the sample will give a false positive result,” Rauert said, meaning the test might falsely indicate the presence of microplastics in the blood when they aren’t actually there. Additionally, false positives can also occur due to interference from other substances in the blood, which can confuse the results and lead to inaccuracies.

Even advanced laboratories face significant challenges in accurately identifying common plastics like PE and PVC in human blood due to interference from other substances in the sample, leading to potential false positives. This raises concerns about the reliability of at-home microplastic tests, with tests being conducted at home in an uncontrolled environment and testing results sent to labs that likely encounter the same limitations.

There are also the risks of false negatives, which is when the analysis says that the blood sample contained no plastics. During shipping, exposure to heat and moisture may cause the sample to lose the microplastics originally contained in the blood smear, and the laboratory may therefore give a negative reading.

What This Means for You

Given the many challenges of using at-home microplastic blood tests, Rauert cautions that at the current stage, these tests may not “provide information for informed health decisions.”

Furthermore, both Cowger and Rauert agree that testing a single drop of blood for microplastics is highly unreliable. As Cowger explains, “I’ve yet to see any peer-reviewed study that recommends analyzing a single drop of blood for microplastics—and that makes me very wary.”

While advances in technology are needed to make at-home tests reliable, experts advise focusing on reducing exposure to microplastics in the home and environment through reducing plastic use, such as eliminating single use plastics from the home and improving air filtration in the home with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter.