1. Asymptomatic Infection Type

Around 80 percent of people infected with WNV do not experience any symptoms. Consequently, most people infected with the disease will never realize they’ve had it.2. West Nile Fever (Non-neuroinvasive disease)

Approximately 20 percent of people infected with WNV will develop West Nile fever, a milder form of WNV, also known as West Nile non-neurological syndrome.3. Neuroinvasive West Nile Disease

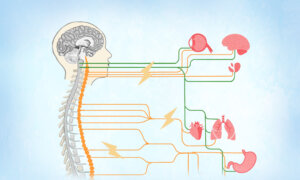

An estimated 1 in 150 people (less than 1 percent) infected with WNV will develop a more severe form of the disease known as neuroinvasive disease or West Nile neurological syndrome. It occurs when the virus affects the central nervous system with symptoms that differ from person to person, making it challenging to diagnose. Even with intensive supportive care, the mortality rate for neuroinvasive WNV infection remains high, as approximately 10 percent of patients may die. There are different types of neuroinvasive disease, including:- West Nile encephalitis: Encephalitis occurs when the virus enters the brain, causing damage and triggering inflammation of the brain.

Symptoms

Symptoms can range from muscle weakness and paralysis to mild confusion and behavioral changes (similar to hysteria), as well as seizures and deep coma.

- West Nile meningitis: Meningitis is inflammation of the meninges (membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord). West Nile meningitis appears very similar to viral meningitis caused by other viruses, so it can be difficult to tell them apart based on symptoms alone.

Symptoms

Similar to West Nile encephalitis, symptoms of West Nile meningitis can include headache, high fever, muscle weakness, disorientation, tremors, convulsions, seizures, paralysis, and coma.

- Meningoencephalitis: Meningoencephalitis is inflammation of both the brain and meninges. WNV has become the leading cause of epidemic meningoencephalitis in North America.

Symptoms

Symptoms include stiffness in the neck muscles, fever, and headache.

- West Nile acute flaccid myelitis: West Nile acute flaccid myelitis closely resembles poliovirus-associated poliomyelitis, both clinically and pathologically. It involves damage to the anterior horn cells in the spinal cord and can lead to severe complications.

Symptoms

West Nile acute flaccid myelitis often manifests as weakness or paralysis in one limb and can take place without any fever or early signs of infection.

Recovery from neuroinvasive disease usually takes one year or more.

Transmission

WNV can spread through several routes, including:- Mosquito bites: WNV circulates in the environment primarily between mosquitoes and birds. Mosquitoes become infected by feeding on infected birds and can then transmit the virus to people through bites. Birds effectively harbor and amplify the virus, and the virus is highly pathogenic to birds in North America, with crows and jays being especially susceptible. The virus has been detected in deceased or dying birds across more than 250 species.

- Blood transfusion: A small number of WNV infections have occurred through blood transfusions. However, since 2003, blood collection agencies in the United States have been screening all donated blood to minimize the risk of WNV infection. Those recently diagnosed with WNV infection should refrain from donating blood or bone marrow for 120 days after the infection.

- Organ or tissue transplantation: Each year in the United States, roughly one organ donor transmits WNV to recipients. The risk of contracting West Nile virus from an organ transplant is uncertain and depends on factors such as the annual number of West Nile cases, the time of year, and the donor’s location. Unlike blood donors, not all deceased organ donors are tested for WNV, although most organ transplant centers screen living donors. Testing deceased donors may be challenging due to the time required for results.

- Pregnancy: Most women who contract WNV during pregnancy deliver infants without WNV infection. However, in a well-documented case of confirmed congenital WNV infection, the mother developed neuroinvasive WNV disease in the 27th week of gestation, and her child was born with cystic brain lesions and chorioretinitis (inflammation of the choroid and retina of the eye).

- Breastfeeding: WNV can potentially be transmitted through breast milk, although this is a rare occurrence. One reported case involved an infant who apparently contracted the virus through breastfeeding but remained asymptomatic.

- Exposure to infected clinical specimens: Laboratory workers are at risk for this type of transmission.

- Donating blood

- Touching pets

- Touching or kissing someone who has the virus: There have been no documented cases of human-to-human transmission of WNV through casual contact, including touching, coughing, sneezing, or sharing a cup.

- Handling infected dead birds: Gloves should still be worn if touching potentially infected dead birds is required.

- Those living in or traveling to areas where WNV has been detected. For instance, WNV is considered endemic, or native, to New York State. Nevertheless, even in regions where the virus is present, the likelihood of getting sick from a mosquito bite is very low.

- Those exposed to mosquito bites during the summer and early fall. The number of WNV cases increases from late August to early September.

- Aged 50 and older: Older people are at the greatest risk of developing severe illness if infected with WNV.

- Immunocompromised: Those with a weakened immune system are also at the highest risk for severe illness caused by WNV.

- Have chronic conditions: Those with cancer, diabetes, alcoholism, hypertension, kidney disease, or heart disease are at a higher risk of experiencing severe health effects from WNV infection.

- Pregnant mothers

- Young children

1. Differential Diagnosis

WNV should be considered in the differential diagnosis when encephalitis or aseptic meningitis is suspected, particularly if caused by:- Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

- Enteroviruses

- Other arboviruses such as La Crosse, St. Louis encephalitis, Eastern equine encephalitis, or Powassan virus.

- Tick-borne diseases, including Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

2. Diagnosis

Health care providers diagnose WNV infection based on:- Symptoms

- History of potential exposure to infected mosquitoes, blood transfusions, and organ transplants

- Lab tests of blood or spinal fluid

3. Tests

Health care providers may order the following tests:- Blood test: IgG antibody seroconversion, or a significant increase in antibody levels, is measured by collecting two blood samples a week apart and testing them with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) blood test. WNV-specific IgM antibodies typically appear three to eight days after illness begins and can persist for 30 to 90 days, though sometimes longer.

Positive IgM results might indicate a past infection. If serum is collected within eight days of illness onset and IgM is not detected, it does not necessarily rule out WNV infection—a follow-up test may be needed. False-positive results can occur due to cross-reactive antibodies from infections with other flaviviruses, recent vaccination with flavivirus vaccines (such as yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis), or nonspecific reactions.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap): A spinal tap can be used to test for the virus, especially in people experiencing symptoms of meningitis. It involves collecting a sample of the fluid surrounding patient’s spinal cord and brain.

- CT scan or MRI: If you experience severe symptoms, your doctor may recommend a CT scan or MRI to check for brain inflammation.

- Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay: Your doctor may use RT-PCR assay to amplify the virus’s genetic material. This method allows for rapid and precise identification of the virus.

- Plaque-reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs): PRNTs can identify the specific flavivirus causing an infection, such as WNV. They can also confirm acute infection by showing a fourfold or greater change in WNV-specific neutralizing antibody levels between blood samples taken during the acute phase and two to three weeks later during the convalescent phase.

- Serum neutralization assays: Neutralization assays are lab tests used to evaluate the ability of antibodies to prevent WNV from infecting cells. The serum neutralization assay can effectively replace PRNTs to detect and quantify WNV antibodies.

- Viral cultures: Viral cultures and tests can detect viral WNV RNA.

- Seizures

- Memory loss

- Brain damage

- Death

- Coma

- Permanent muscle weakness

- Respiratory paralysis: Respiratory paralysis is a severe complication of West Nile acute flaccid myelitis, and it may necessitate mechanical ventilation.

- Neuropathy: Neuropathy refers to damage or dysfunction of one or more peripheral nerves, resulting in numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, and pain, usually in the hands and feet.

- Vitritis: Vitritis is inflammation of the vitreous body within the eye.

- Chorioretinitis: Chorioretinitis is inflammation of the choroid, a retinal lining located deep inside the eye.

- Retinal hemorrhages: Bleeding into the retina

- Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas

- Rhabdomyolysis: Rhabdomyolysis is a serious medical condition where damaged skeletal muscle rapidly breaks down, leading to the release of muscle contents into the bloodstream.

- Central diabetes insipidus: Central diabetes insipidus is a condition characterized by the deficiency of antidiuretic hormone, leading to excessive urination and thirst.

1. West Nile Fever (Non-neuroinvasive Disease)

If you have a mild case, you can recover at home by resting, staying hydrated, and taking pain or fever-reducing medication (such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen), as there is no specific medication for WNV infection. Although you might feel well enough to continue your normal activities, it’s important to ask your doctor if you should stay home. Most people recover completely from mild WNV cases.2. Neuroinvasive West Nile Disease

If your WNV infection is severe, you may need to be hospitalized to fight the illness and reduce the risk of developing complications with:- Long-term ICU care: Patients with severe neurological symptoms from WNV often need extended ICU care and long-term physical and occupational therapy, since post-infection, they may experience significant motor, cognitive, and fine motor impairments.

- Intravenous (IV) fluids: IV fluids help maintain hydration and support overall bodily functions.

- Breathing support with a ventilator: Acute respiratory failure can develop quickly, often necessitating extended use of a ventilator for support.

- Prevention of secondary infections and other illnesses: Common secondary infections include pneumonia and urinary tract infections. When the central nervous system is affected, many patients become bedridden, which can lead to issues such as pressure sores, aspiration (inhaling food or liquid into the lungs), and deep vein thrombosis (blood clots in the veins). Thus, preventive measures are necessary.

- Certain intravenous treatments: IV treatments such as interferon or ribavirin may have potential benefits in humans, but use is limited due to mixed outcomes and potential adverse events.

- Nursing care

- Close monitoring: Patients with encephalitis need careful monitoring for high intracranial pressure and seizures, while those with encephalitis or acute flaccid paralysis should be closely watched for difficulty maintaining their airways.

- Prevention: A proactive mindset towards health and prevention can prompt individuals to take necessary precautions, such as using insect repellents, wearing protective clothing, and eliminating mosquito breeding sites, to reduce the risk of infection.

- Early detection and response: People who are aware of the WNV symptoms and have a vigilant mindset are more likely to seek medical attention promptly if they suspect an infection. Early detection can lead to more effective management of the disease and better outcomes.

- Adherence to treatment: A positive and cooperative mindset can improve adherence to medical advice and treatment plans.

- Psychological impact: The stress and anxiety related to dealing with severe WNV illness can affect patients’ overall well-being and recovery. A resilient mindset and mental health support can help them cope better.

1. Natural Polyphenols

Polyphenols are compounds found in plant-based products such as tea, chocolate, fruits, and vegetables. They protect organisms from external stress and help eliminate reactive oxygen species, with the potential to positively impact human health.- Delphinidin: Delphinidin is a polyphenolic natural pigment found in brightly colored fruits and vegetables, especially pomegranate. It is a strong angiogenic inhibitor with cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory properties. A 2017 study, found delphinidin was able to block WNV infection in cell culture, particularly by targeting the early stages of the virus’s life cycle. It significantly reduced the virus’s ability to infect cells by affecting its attachment and entry into cells and directly destroyed WNV particles, making it a strong candidate for future antiviral treatments.

- Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): Epigallocatechin gallate is a natural compound mainly found in green tea, but also in various other fruits, nuts, and herbs such as cranberries, strawberries, apples, and pecans. EGCG offers numerous health benefits, including reducing inflammation, aiding in weight loss, lowering cholesterol levels, and providing cardiovascular protection. The same 2017 study found EGCG to be capable of inhibiting WNV production. Similar to delphinidin, EGCG prevented the virus from attaching to and entering cells, and also directly damaged the virus, making it less infectious. When EGCG was used at 37 C (body temperature), it was even more effective. Treating WNV with EGCG before it infected cells greatly reduced the amount of the virus and its genetic material RNA inside the cells.

2. Combined Monoterpene Alcohols

Monoterpene alcohols, also called monoterpenols, are naturally occurring acyclic compounds found in many plants, especially in essential oils. A 2016 study showed that a combination of monoterpene alcohols from the Melaleuca alternifolia plant could destroy WNV and reduce the amount of virus and the number of infected cells. When tested in mice, this treatment delayed the onset of illness, helped prevent weight loss, and lowered the amount of virus in the brain. The researchers concluded that this combination could be a promising treatment for WNV infection.3. Human Immunoglobulin

Human immunoglobulin is a medical product made from the combined blood plasma of many people. It contains a high amount of special proteins called gamma globulins, which are important for the immune system. These proteins, also known as antibodies, help the body fight off infections. During the 2000 WNV outbreak in Israel, a 70-year-old woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who had fallen into a coma due to WNV encephalitis recovered after being treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).1. Infection Risk Reduction in Humans

As there is no human vaccine available for WNV, prevention is crucial. The best way to protect against WNV is to prevent mosquito bites. In areas with West Nile virus, only a small percentage of mosquitoes are typically infected. The infection rate is often around 10 percent during outbreaks. It’s difficult to distinguish infected mosquitoes from those that are not. The following measures can be helpful:- Use screens: Install screens on doors and windows, and keep doors and windows closed if they are not screened.

- Wear protective clothing: When outdoors, wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants, shoes, and socks to minimize mosquito exposure. Avoid wearing dark-colored clothing, as it tends to attract mosquitoes. Tuck your pants into your socks and shirt into pants for added protection.

- Use mosquito netting: Use mosquito netting over cribs and strollers to protect babies and toddlers.

- Apply insect repellents: Use insect repellents as directed, choosing products with EPA-approved ingredients such as DEET and picaridin. Do not apply insect repellents to infants under 2 months old. Children over 3 years old can use oil of lemon eucalyptus. When applying a repellent to a child, put it on your hands first then apply it to the child, avoid their eyes and mouth, and use sparingly around their ears. Do not apply it to their hands to prevent ingestion. You can also spray your clothing with insect repellents. Avoid applying repellents to cuts, wounds, or irritated skin. After coming indoors, wash treated skin with soap and water.

- Limit outdoor activity: Minimize outdoor activities around dawn and dusk, when mosquitoes are most active.

- Eliminate breeding sites: Most mosquitoes don’t travel far and usually stay near their breeding sites, so you’re most likely to be bitten by mosquitoes from your own backyard. Mosquitoes can develop from eggs into adults in as little as one week, and they don’t need much water to do so.

- Remove standing water: Remove standing water from containers such as buckets, trash cans, tires, and even tiny containers such as bottle caps left outdoors, and regularly clean birdbaths, dog bowls, and flowerpots to prevent mosquito breeding. You can also drill holes in the bottom of used containers to prevent water from collecting.

- Maintain swimming pools: If you have a swimming pool, promptly remove water from pool covers and ensure the pump is circulating properly. Clean and chlorinate swimming pools, outdoor saunas, and hot tubs.

- Clean drains: Regularly clear leaves and twigs from eavestroughs, storm drains, and roof gutters during the summer.

- Community spraying: Community mosquito spraying can help reduce mosquito breeding.

- Handle sick/dead animals properly: To reduce the risk of animal-to-human transmission, wear gloves and protective clothing when handling sick animals, their tissues, or during slaughtering and culling procedures.