- Dizziness

- Lightheadedness

- Fainting

- Dim or blurry vision

- Weakness

- Unsteady gait

- Slurred speech

- Exercise-induced syncope (fainting)

Urinary Dysfunction

- Increased urinary frequency

- Nocturia (the need to urinate frequently during the night)

- Urinary urgency

- Stress incontinence

Sexual Dysfunction

- Impotence

- Loss of sex drive

- Dry or retrograde ejaculation

Gastrointestinal Problems

- Intermittent diarrhea

- Explosive diarrhea (in severe cases)

- Nocturnal diarrhea

- Rectal incontinence

- Constipation

- Abdominal pain

- Acid reflux

- Heartburn

Cardiovascular Issues

- Heart palpitations

- Chest discomfort

- High or low heart rate

- High or low blood pressure

- Blood pooling, which is when blood cannot return to the heart properly and collects in the veins

Neurological Problems

- Mood swings

- Anxiety

- Forgetfulness

- Migraines

Other Symptoms and Signs

- Abnormal sweating

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Drooling or dry mouth

- Vertigo

- Dry or watery eyes

- Trouble swallowing

- Clammy or pale skin

- Viral infections: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus, herpes viruses, flavivirus, enterovirus 71, and lyssavirus infections can cause autonomic dysfunction.

- Lyme disease: Lyme disease can lead to the development of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other forms of dysautonomia.

- Diabetes: Diabetes can cause diabetic autonomic neuropathy.

- Parkinson’s disease: The findings of a 2019 study indicate that autonomic dysfunction is linked to disrupted white matter, impaired brain connectivity, and cognitive decline in newly diagnosed patients with Parkinson’s disease.

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis: This is also known as chronic fatigue syndrome.

- Long COVID: A 2022 study found that symptoms of dysautonomia are common in people with long COVID. The most affected areas of dysautonomia include digestive issues, problems with sweating and other secretions, and difficulty standing up without feeling dizzy or faint. Older patients also tend to experience more orthostatic intolerance, which is when standing up causes changes such as a drop in blood pressure.

- COVID-19 vaccination: As per a 2023 study, some people experience chronic fatigue and dysautonomia after receiving the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine, a condition referred to as post-acute COVID-19 vaccination syndrome (PACVS). Researchers found that PACVS patients who had symptoms of dysautonomia for at least five months after vaccination showed different blood markers compared to healthy individuals. These differences included higher levels of certain antibodies and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which can help distinguish PACVS from a normal postvaccination response. The exact number of vaccinated individuals affected by PACVS is unknown, but current estimates suggest an incidence of about 0.02 percent.

- Vasovagal syncope: Vasovagal syncope, also known as neurocardiogenic syncope, is the most common form of dysautonomia, affecting 22 percent of Americans. While many experience only occasional fainting spells, severe cases can involve fainting multiple times a day. Vasovagal syncope is a type of fainting caused by an abnormal or exaggerated response of the body’s automatic functions to stimuli such as standing up or strong emotions. The exact cause isn’t fully understood, but it involves changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and activation of specific heart fibers.

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): POTS is characterized by an abnormally rapid increase in heart rate when moving from a sitting or lying down position to standing. It is one of the more common types of dysautonomia. Before COVID-19, POTS affected about 1 percent of teenagers and between 1 to 3 million Americans overall. Some sources suggest that this number has increased by 1 million to 3 million since the pandemic. For more details on the condition, please refer to The Essential Guide to POTS.

- Orthostatic and postprandial hypotension: Orthostatic hypotension is a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing, leading to reduced blood flow to the brain. It often causes dizziness, lightheadedness, or fainting. Orthostatic hypotension affects approximately 6 percent of the general population and is more common in older adults, affecting 10 percent to 30 percent of this age group. Similarly, postprandial hypotension is when blood pressure drops suddenly after a meal. During digestion, the body increases blood flow to the stomach and intestines, causing the heart to pump faster and blood vessels to constrict to maintain overall blood pressure. However, in people with postprandial hypotension, the heart doesn’t speed up enough, and blood vessels fail to constrict properly, leading to a drop in blood pressure. It affects around 40 percent of older adults over 65.

- Diabetic autonomic neuropathy: Diabetic autonomic neuropathy is a common form of dysautonomia, affecting 20 percent of individuals with diabetes. It is a severe diabetes complication linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality.

- Multiple system atrophy (MSA): MSA is a rare, fatal neurodegenerative disorder affecting adults over 40. It shares similarities with Parkinson’s disease but progresses more rapidly, often leaving patients bedridden within two years of diagnosis and leading to death within five to 10 years. Approximately 350,000 people worldwide are affected by MSA. Its cause is largely unknown, but the condition is associated with the deterioration and atrophy of specific brain areas, including the cerebellum, basal ganglia, and brainstem, along with the accumulation of alpha-synuclein, a protein involved in nerve cell communication.

- Familial dysautonomia: Also known as Riley-Day syndrome, familial dysautonomia is a rare inherited disorder that affects the autonomic and sensory nervous systems. It causes unstable blood pressure, reduced sensitivity to pain and temperature, and a lack of tears when crying. Individuals with familial dysautonomia may experience an autonomic crisis characterized by sudden high blood pressure, elevated heart rate, and vomiting or retching. Familial dysautonomia is caused by a genetic mutation in the ELP1 gene (also known as the IKBKAP gene), which produces a protein found in various cells, including brain cells.

- Baroreflex failure: Baroreflex failure occurs when the body’s baroreflex system, which regulates blood pressure, fails. This system sends signals to the brain to adjust blood pressure by activating the parasympathetic nervous system to lower heart rate when blood pressure is high and deactivating the sympathetic nervous system to reduce heart rate and dilate blood vessels. When blood pressure is too low, the opposite occurs. As a result of baroreflex failure, blood pressure fluctuates between being too high and too low, causing symptoms such as dizziness, fainting, headaches, sweating, and skin flushing. It is a rare condition often caused by neck trauma from surgery or radiation therapy for cancer, although in some cases, the cause is unknown.

- Pure autonomic failure (PAF): PAF, also known as Bradbury-Eggleston syndrome, is a rare form of dysautonomia characterized by the degeneration of autonomic nervous system cells. Its hallmark symptom is severe orthostatic hypotension, which leads to dizziness, fainting, and syncope. It more commonly affects men and typically occurs in middle-aged to older adults. As per estimation, fewer than 5,000 Americans live with this condition. PAF is linked to the abnormal buildup of alpha-synuclein, which is also seen in conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, MSA, and dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST): IST is a chronic condition where the heart maintains a normal rhythm but beats excessively fast, with a resting heart rate above 100 beats per minute (bpm), compared to the normal range of 60 to 100 bpm. It affects approximately 1 percent of the middle-aged population, with a higher prevalence in females. The cause of IST is unknown. One theory suggests that the sinoatrial node may have an abnormality, or the individual might be overly sensitive to adrenaline, a hormone that increases heart rate.

- Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG): AAG is a rare form of dysautonomia wherein the immune system attacks receptors in the autonomic ganglia, a part of the peripheral ANS. It can present with either rapid or progressive symptom onset and is often linked to high levels of ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibodies (g-AChR antibodies). AAG affects individuals of all ages and both sexes, with about 100 cases diagnosed annually in the United States.

- Age: POTS and vasovagal syncope is often more common among teens and young adults, causing 85 percent of fainting instances in people under 40. In people aged 50 and older, dysautonomia is usually associated with a neurodegenerative disease.

- Sex: POTS is most commonly observed in women of childbearing age, typically between 15 and 50 years old.

- Ethnicity: People of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at a higher risk of dysautonomia, especially familial dysautonomia, which affects almost exclusively this population.

- Diabetes: Diabetics are prone to developing diabetic autonomic neuropathy.

- Alcoholism: Excessive drinking is known to affect the ANS.

- Injury or surgery: An event that damages the ANS or brain can lead to dysautonomia.

- Vitamin deficiencies: Examples include vitamin B12 and vitamin D deficiencies.

- Deconditioning: Deconditioning is the loss of physical function due to lack of activity, extended bed rest, or a very sedentary lifestyle.

- Certain medical conditions: These conditions include amyloidosis, celiac disease, mitochondrial diseases, mast cell disorders, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), various autoimmune diseases, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

- Tilt table test: A tilt table test is used to evaluate how the nervous system regulates blood pressure and heart rate. During the test, the individual lies on a table that tilts at different angles while he or she is connected to monitors for blood pressure, oxygen levels, and heart activity. People with dysautonomia may faint when tilted beyond 180 degrees due to their nervous system’s inability to regulate properly. This test is the “gold standard” in testing for dysautonomia.

- Breathing tests: Breathing tests assess how the heart rate responds to slow, deep breathing for 1.5 minutes at a pace of six breaths per minute.

- Active stand test: During the active stand test, the individual lies down quietly for at least 10 minutes to measure baseline blood pressure and heart rate. He or she then stands up and remains upright for 10 minutes, with blood pressure and heart rate measured at regular intervals (e.g., two, five, and 10 minutes).

- Orthostatic vitals test: An orthostatic vitals test, performed by trained staff in a doctor’s office, provides valuable data on the patient’s response to orthostatic stress and can confirm suspected dysautonomia without costly diagnostic tests, such as the tilt table test. Most clinicians today confidently use this test to confirm autonomic disorders.

- Sweating tests: Sweating tests evaluate the function of the nerves responsible for controlling sweat production.

- Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART): The QSART test quantitatively measures the function of sweat glands controlled by small nerve fibers, evaluating the autonomic nerves responsible for regulating sweating.

If necessary, additional tests may be performed, including:

- Valsalva maneuver: The Valsalva maneuver involves forcefully exhaling against a closed airway to evaluate how autonomic nerves regulate heart function.

- Cold pressor test: This test involves immersing a hand or foot in ice water for one to three minutes while monitoring blood pressure and heart rate.

- Heart rate variability (HRV) monitoring: HRV is a useful biomarker for providing insight into various bodily functions. People with dysautonomia often have low HRV.

- Blood tests: Blood tests, including a complete blood count, evaluate iron levels, kidney and liver function, thyroid function, and other factors such as electrolytes, glucose, and creatinine to identify underlying medical conditions.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): An electrocardiogram is a painless test that monitors the heart’s electrical activity and helps assess its function while ruling out other heart conditions.

- Holter monitor: A Holter monitor records every heartbeat over a 24-hour period to analyze heart rate and rhythm through continuous ECG monitoring.

- Falling: This is a complication of fainting.

- Bone fractures: Falling may result in fractures.

- Stroke: Stroke can be caused by decreased blood supply to the brain.

- Cardiovascular conditions: These can result from orthostatic hypotension. Examples are chest pain and heart failure.

- Thromboembolism: This is a complication of POTS caused by a blood clot that blocks a blood vessel.

- Depression and anxiety: POTS, as well as other types of dysautonomia, can lead to this.

- Dystonia: Dysautonomia-related conditions such as CRPS can cause abnormal muscle postures.

- Adrenal insufficiency: Dysautonomia can cause the body to not produce enough hormones like cortisol, resulting in adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease).

- Increased risk of death: Orthostatic hypotension is linked to a significant increase in all-cause mortality.

1. Lifestyle Adjustments

For many types of dysautonomia, lifestyle changes are first-line treatments. These may include:

- Boosting salt and water intake: Many people with dysautonomia have low blood volume, which can be improved by increasing fluid and electrolyte intake. Sodium is particularly important as it helps the body retain water.

- Avoiding heavy meals: Eating large, heavy meals high in fat and carbohydrates can worsen symptoms such as dizziness, as blood is diverted to the stomach for digestion. Smaller, more frequent meals are generally more well-tolerated, and they can regulate blood sugar levels and prevent low blood pressure after meals.

- Avoiding triggers: Identifying triggers that worsen autonomic symptoms is crucial. Common triggers include medication side effects, dehydration, heat, exercise, alcohol, caffeine, high-carb meals, illness, stress, pain, high altitude, prolonged rest, surgery, and allergic reactions.

- Exercising regularly: Exercise is essential for managing dysautonomia symptoms and should include aerobic reconditioning and strength training. It is important for patients to start gradually and progress slowly. Initially, exercises in a reclined position, such as using a rowing machine, recumbent bike, or swimming, are recommended to minimize orthostatic stress.

- Practicing good sleep hygiene: Sleep disorders are common in individuals with dysautonomia. Restorative sleep supports healing and reduces stress. It’s recommended to avoid stimulating activities 30 minutes before bedtime.

- Using counter-pressure maneuvers: To reduce orthostatic symptoms caused by low blood pressure, counter-pressure maneuvers can be helpful, including isometric maneuvers (holding a position by tensing large muscles) such as leg crossing with muscle tensing and whole-body tensing. Positional maneuvers like squatting or dynamic muscle pumping (using muscle movement to help pump blood), such as postural swaying and toe extension, may also help.

- Taking supplements: Supplementation is important if an individual is deficient in vitamin B12 or vitamin D.

- Wearing compression garments: Compression clothing, such as socks, stockings, leggings, bodysuits, and abdominal binders, helps reduce blood pooling by pushing blood back toward the heart.

2. Medication

Some medications are used to manage symptoms of autonomic disorders. However, most are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating dysautonomia and are used “off-label.” Although they have been successful in helping some patients, they have various side effects. Medications used to treat dysautonomia include:

- Fludrocortisone: Fludrocortisone is used to manage POTS, orthostatic intolerance, and orthostatic hypotension. It increases salt retention and blood volume, which helps raise blood pressure.

- Midodrine: Midodrine constricts blood vessels, raises blood pressure, and helps prevent fainting.

- Beta-blockers: Beta-blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol help manage POTS and hyperadrenergic hypertension by reducing heart rate, blood pressure, and adrenaline effects, which can prevent fainting.

- Pyridostigmine: Pyridostigmine helps manage chronic orthostatic hypotension by increasing acetylcholine levels, which can reduce heart rate, boost blood pressure, and enhance muscle strength.

- Clonidine: Clonidine helps reduce blood pressure and sympathetic nervous system activity. It also improves sleep, benefiting patients with hypertension and excessive sympathetic stimulation.

- Ibuprofen: Ibuprofen constrains blood vessels and blocks inflammatory prostaglandins.

- Amphetamine: Amphetamine helps manage chronic orthostatic intolerance by tightening blood vessels, increasing alertness, improving cognitive function and brain fog, and reducing appetite.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): SSRIs alleviate orthostatic tolerance and reduce venous blood pooling. They also help improve mood and reduce anxiety.

- Erythropoietin: Erythropoietin increases blood volume and blood pressure, making it particularly beneficial for anemic patients or those with chronic fatigue.

- Ivabradine: Ivabradine lowers heart rate, alleviates angina pectoris, and improves IST and POTS.

- Yohimbine: Yohimbine increases blood pressure, making it useful for conditions like chronic autonomic failure and MSA.

- H1 and H2 antihistamines: These constrict blood vessels and help reduce inflammation in the gut.

- Botulinum toxin injections: Botox injections relieve dystonia by relaxing contracted muscles and restoring normal hand or foot positions.

- Droxidopa: Droxidopa, an orally active synthetic precursor of norepinephrine, has been approved by the FDA for treating symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension.

3. Physical Therapy

Exercises and therapies used to treat dysautonomia may include:

- Reclined exercises: Patients who cannot stand can begin with exercises performed in a horizontal or reclined position.

- Aquatic therapy: Aquatic therapy is beneficial as the water pressure on the body helps support movement and reduces strain.

- Manual physical therapy: This therapy focuses on relieving nerve tightness and improving range of motion, which can help increase exercise tolerance.

- Craniosacral therapy: Craniosacral therapy uses soft-tissue manipulation techniques to improve musculoskeletal health and function by releasing tension in the body and facial tissues.

4. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

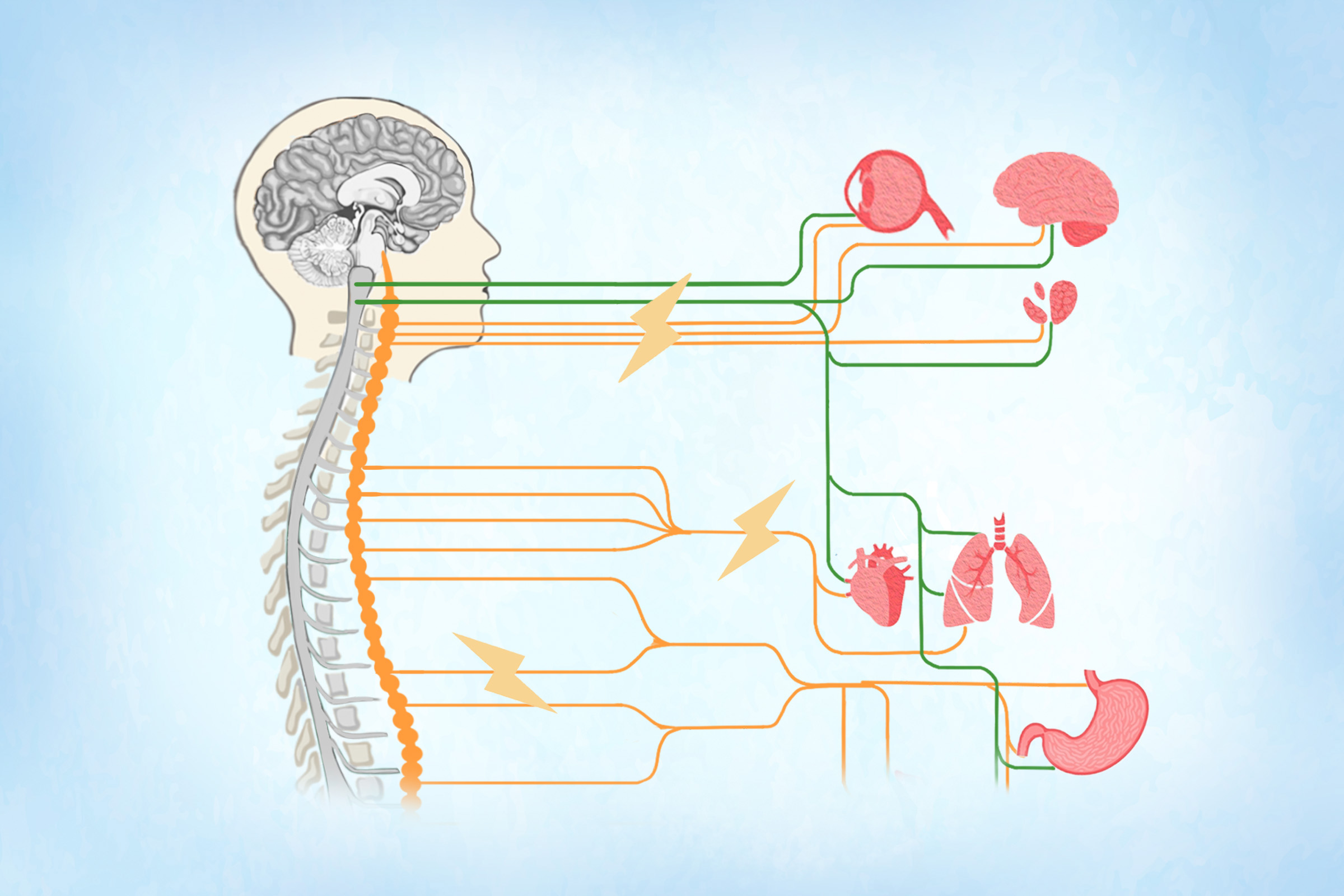

The vagus nerve is the primary nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system, relaying signals from the brain to the gut and heart. There are invasive (device-based) and noninvasive ways to stimulate the vagus nerve. For instance, simply humming, grounding to the Earth, and singing can stimulate this nerve. Emerging research into VNS shows promise for treating dysautonomia.

1. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements

Personalized dietary strategies and targeted supplements can help alleviate the symptoms affecting multiple organ systems in individuals with dysautonomia.

- Diarrhea or bloating: The fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet or gluten-free diet, soluble fiber, probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) treatment may help with gastrointestinal disturbances.

- Constipation: Fiber supplements and SIBO treatment may help.

- Osteoarticular symptoms: Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and manganese ascorbate may help with joint issues.

- Musculoskeletal pain: Carnitine, gamma-linolenic acid, and coenzyme Q10 may help with inflammation.

- Fatigue: Coenzyme Q10, magnesium, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and alpha-lipoic acid supplements may alleviate fatigue.

Phosphatidylserine is a neuroprotective fatty substance available as a supplement generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA but not approved for any specific medical condition.

2. Yoga

Yoga has been found to positively affect cardiovascular autonomic function. A 2021 randomized controlled trial found that guided yoga therapy was more effective than conventional or nonpharmacological therapy in reducing symptoms in patients with recurrent vasovagal syncope (VVS).

3. Acupuncture

A 2013 study found that electroacupuncture at PC-6 (neiguan) acupoint enhanced orthostatic tolerance in healthy individuals by improving cardiac function and stimulating the sympathetic nervous system. This point is in the center of the right forearm, about three finger-widths above the wrist crease. Please consult a certified acupuncturist for guidance.

4. Tai Chi

A 2012 study found that tai chi training helped reduce balance impairments in patients with mild-to-moderate Parkinson’s disease while improving functional capacity and reducing the risk of falls.

- Treating diabetes and other conditions that can cause dysautonomia.

- Avoiding drugs or substances that may affect the ANS, if possible. Examples include alcohol, MAO inhibitors, antihypertensives (prazocin, clonidine, alpha-methyldopa), barbiturates, antipsychotics (phenothiazines), and tricyclic antidepressants.

- Avoiding viral infections that can lead to dysautonomia.

- Leading a healthy lifestyle that includes getting enough sleep, exercise, and eating a balanced diet.

- Staying hydrated and adding dietary salt or electrolytes as needed. Keep in mind: Not all salt is created equally. Rock salt and sea salt are the most nutritious, but rock salt, such as Himalayan pink salt, is less likely to contain microplastics.

- Identifying and avoiding triggers.

- Managing stress and employing strategies to soothe the vagus nerve, such as deep breathing, yoga, meditation, grounding, and humming.