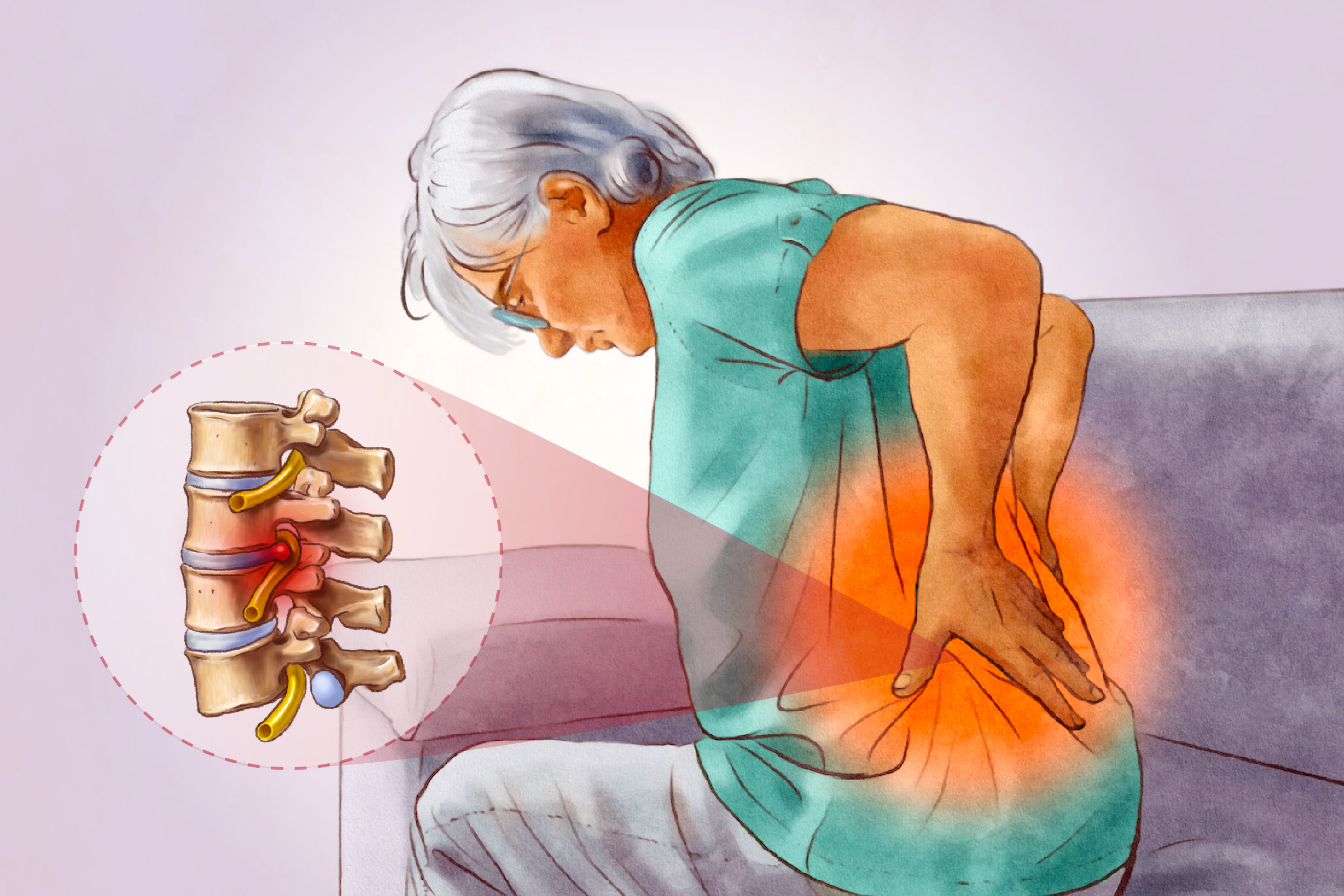

Primary Symptoms

Sciatica symptoms can vary widely in intensity and presentation, but they most often follow a recognizable pattern. Below are the most common signs people experience:

- Pain: Typically affects one side of the body and can range from mild tingling or a dull ache to sharp, burning pain or electric shock-like jolts

- Numbness: Occurs in the leg, calf, or sole of the foot

- Muscle weakness: Appears in the affected leg

- Abnormal sensations: Includes tingling, pins and needles, or intense hot or cold sensations

- Muscle spasms: Occur in the lower back or leg

Pain Triggers and Aggravating Factors

Sciatica pain may worsen with:

- Sitting for long periods

- Standing for extended periods

- Sneezing, coughing, or laughing

- Bending backward

- Walking long distances

- Climbing stairs

- Straining during bowel movements

In severe cases, the pain can be so intense that it limits movement or causes the foot to drag while walking. If the cauda equina—a bundle of nerves at the base of the spinal cord—is affected as well, it can lead to a loss of bladder and bowel control.

- Severe numbness in the genital area

- Difficulty urinating or loss of bladder and bowel control

- Progressive muscle weakness

- Foot dragging while walking

- Herniated disc: A herniated disc occurs when a spinal disc becomes damaged and its soft inner gel bulges or leaks through a tear in the outer layer, pressing on nearby nerve roots and causing inflammation.

- Spinal stenosis: Spinal stenosis involves narrowing of the spaces within the spine, which puts pressure on the spinal cord or exiting nerves—often due to age-related degeneration.

- Degenerative disc disease: Degenerative disc disease results from the natural aging process, during which spinal discs lose hydration, become thinner and less flexible, and may irritate nearby nerve roots.

- Piriformis syndrome: Piriformis syndrome develops when the piriformis muscle in the buttock irritates or compresses the nearby sciatic nerve, often due to tightness, inflammation, or spasm.

- Bone or muscle injuries: Bone or muscle injuries include trauma such as pelvic fractures or dislocations that cause inflammation, swelling, or direct injury to the sciatic nerve.

- Spondylolisthesis: Spondylolisthesis happens when a vertebra slips out of place, narrowing the spinal nerve openings or compressing nearby nerve roots in the lower back.

- Pregnancy: Physical and hormonal changes in late pregnancy can shift the center of gravity and loosen ligaments, potentially affecting the sciatic nerve.

Sciatica can also arise from causes beyond disc herniation, including spinal masses, surgical complications, joint issues, nerve damage from diabetes, bone spurs, and, in many instances, an unknown origin.

- Age-related factors: Wear and tear over time increases the risk of sciatica, especially in those 40 or older.

- Sex-related factors: Men between the ages of 30 and 50 have a higher risk of sciatica.

- Physical factors: Tall height and excess body weight may place extra strain on the spine.

- Lifestyle factors: Habits such as smoking or chronic stress may contribute to inflammation or poor spinal health.

- Occupational factors: Jobs that involve heavy lifting, prolonged sitting, driving, or contact sports may raise the risk of sciatica.

- Health-related factors: Poor general health, a history of back surgery, or chronic lower back pain may increase vulnerability.

- Mechanical factors: Improper movement or posture during daily activities—such as lifting heavy objects or prolonged sitting—may aggravate the sciatic nerve and increase risk.

By Duration

Sciatica can be categorized by how long symptoms persist. Some cases resolve quickly, while others become long-term and require more ongoing management.

By Affected Area

The condition can also be described based on where the pain occurs. While most people experience sciatica in one leg, other patterns are possible.

- Unilateral sciatica: Affects one leg and is the most common form

- Bilateral sciatica: Affects both legs simultaneously; a rare form that may indicate a serious condition

- Alternating sciatica: Involves pain that switches between legs; an uncommon form often associated with sacroiliac joint dysfunction

By Pain Pattern

Sciatica may also be classified based on where the pain is most prominent—either in the lower back or the buttocks.

Physical Examination Tests

Diagnosing sciatica mainly involves a thorough medical history and physical exam, during which a doctor evaluates the patient’s symptoms—especially the type and location of their leg pain.

- Straight leg raising test: A common physical exam used to assess sciatica, particularly when a herniated disc is suspected. While the patient lies flat on the back with legs extended, the doctor lifts the affected leg without bending the knee. The test is considered positive if it reproduces pain or abnormal sensations, especially when the leg is elevated to less than 70 degrees and the discomfort radiates below the knee. This may indicate nerve root irritation or compression.

- Crossed straight leg raise: A variation of the straight leg test used to support the diagnosis of a herniated disc. While the patient lies flat on their back, the doctor lifts the unaffected leg while keeping it straight. A positive result occurs when this movement triggers pain that radiates down the opposite, affected leg.

- Femoral stretch test: A physical exam used to identify nerve root irritation higher in the spine. With the patient lying face down, the doctor bends the knee of the affected leg to a 90-degree angle and gently lifts the thigh off the table. Pain in the front of the thigh during this maneuver may suggest a herniated disc.

If symptoms are severe, especially concerning, or persist for more than a few weeks, a doctor may recommend additional tests:

Imaging Tests

Diagnostic imaging is most useful when it may affect treatment decisions. It is typically considered for patients with severe symptoms that do not improve after about six weeks of conservative care, or if weakness or numbness is present. Imaging can help determine whether a herniated disc with nerve root compression exists—possibly indicating the need for surgical intervention. Techniques may include:

- X-rays: Used to detect bone-related issues such as osteoarthritis or spinal fractures

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Provides detailed images of soft tissues, including nerves, tumors, and spinal damage

- Computed tomography scans: Offer 3D views of the spine and can detect structural abnormalities

If imaging tests are inconclusive or further clarity is needed, a doctor may order electrodiagnostic tests.

Exercise

Pilates and strength exercises may help improve pain and function with chronic lower back pain, including sciatica. Many health care providers recommend performing these exercises under the supervision of a trained physical therapist. Light activities—such as walking, swimming, or aqua therapy—along with gentle stretching of the lower back and hamstrings, can aid recovery. Specific exercises may be recommended based on the underlying cause of sciatica.

Massage Therapy

Massage therapy may help relieve sciatica symptoms in several ways, and many people experience some improvement in both pain and function with regular treatment:

- Muscle relaxation: Loosening tight muscles can ease tension around the sciatic nerve and reduce pressure.

- Improved circulation: Increased blood flow may support healing and help reduce inflammation in the affected area. Massage therapy has been shown to enhance circulation by promoting the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to tissues and aiding in the removal of metabolic waste—thereby encouraging recovery.

- Endorphin release: Massage may stimulate the release of endorphins—the body’s natural pain relievers—which can help reduce discomfort. By promoting relaxation and the release of feel-good hormones, massage may also support the body’s detoxification processes and ease pain symptoms.

Cold and Heat Therapy

Cold and heat therapy may provide temporary relief from lower back pain, though effectiveness can vary depending on the underlying cause. Cold therapy, such as applying an ice pack for 20 minutes every two hours, may be most helpful in the early stages of pain. However, some people with sciatica still find brief cold applications useful for reducing inflammation and numbing pain.

Common Herbs

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials suggested that some common herbs and spices may reduce pain associated with sciatica and radiculopathy.

Conservative Treatments (First-Line)

Initial treatment for sciatica often focuses on conservative measures aimed at reducing pain, calming inflammation, and improving function without the need for surgery.

Advanced Treatments

1. Injections

- Laminotomy/Laminectomy: Removal of a portion of bone to relieve pressure on the nerve

- Discectomy: Removal of damaged disc material

- Spinal fusion: Permanent connection of two or more vertebrae to improve spinal stability

Integrative Treatments

Complementary and integrative therapies may offer additional relief for sciatica, especially for people seeking nondrug, nonsurgical options. When used alongside conventional treatment, these approaches may help reduce symptoms, improve function, and support long-term recovery.

Prolonged Pressure

One key factor is avoiding prolonged pressure on the buttocks—such as sitting or lying down for extended periods. Maintaining strong back and abdominal muscles becomes especially important with age to support the spine and reduce strain on the sciatic nerve.

Exercise

Regular exercise can help prevent sciatica by improving overall fitness, maintaining a healthy weight, and strengthening core muscles. Aerobic activities such as walking or swimming enhance general strength, while specific exercises—like pelvic tilts, abdominal curls, and knee-to-chest stretches—help stabilize the spine and reduce strain on discs and ligaments. However, stretching should be done with caution, as it can worsen pain in some people.

Posture

Good posture also plays a role in prevention. Slouching should be avoided, and chairs should be adjusted so that feet rest flat on the floor, knees remain slightly bent, and the lower back is supported—using a small pillow if needed. It’s best to sit with feet flat rather than crossed and to avoid staying in one position for too long.

Proper Lifting Techniques

Using proper lifting techniques is key to preventing back injuries. It’s important to keep the hips aligned with the shoulders and avoid twisting. Instead of bending at the waist with straight legs, one should bend at the hips and knees to lift objects safely.

- Lasting numbness or weakness in the affected leg

- Abnormal sensations, such as tingling or “pins and needles”

- Progressive worsening of pain over time

- Reduced motor strength in the affected leg

- Loss of bladder or bowel control

- Permanent nerve damage

- Recurring or worsening herniated discs