Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), also called postural autonomic tachycardia, is a condition marked by an unusually rapid rise in heart rate when transitioning from a sitting or lying position to standing. This prevalent blood circulation disorder is estimated to affect between 1 and 3 million Americans. POTS is also a form of dysautonomia, a disorder of the autonomic nervous system.

POTS stands for the following:

- Postural: your body’s posture or position

- Orthostatic: drop in blood pressure upon standing after sitting or lying down

- Tachycardia: rapid heart rate

- Syndrome: a collection of symptoms

There are two main types of POTS and several subtypes. POTS is either primary or secondary. It is called primary when there isn’t an exact known cause. Secondary means it’s caused by a known underlying condition that can potentially cause autonomic neuropathy, such as diabetes, Lyme disease, or autoimmune disorders.

The different subtypes of primary POTS include the following:

- Neuropathic: Neuropathic POTS is associated with damage to the small fiber nerves, which regulate blood vessel constriction in the limbs and abdomen, leading to blood pooling in the lower extremities. According to one 2007 study, about 50 percent of POTS patients show signs of nerve damage affecting sweating. These nerve problems cause blood to pool in the legs, often causing a bluish color in the skin.

- Partial dysautonomic: Partial dysautonomic POTS involves mild damage to nerves that control involuntary bodily functions (peripheral autonomic neuropathy), particularly affecting the heart rate and peripheral blood vessels. This damage makes it difficult for the body to regulate blood pressure effectively, especially when standing, leading to blood pooling in the lower body.

- Hyperadrenergic: Hyperadrenergic POTS is characterized by elevated levels of the stress hormone norepinephrine and overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the body’s response to threatening situations. Approximately 30 percent to 60 percent of POTS patients have this subtype. In some cases, a genetic mutation in the norepinephrine transporter (SLC6A2) can lead to deficient norepinephrine transport, causing rapid heartbeats, palpitations, tremors, high blood pressure, and anxiety. Certain medications, including some antidepressants and stimulants, can also block norepinephrine transport, so they must be ruled out.

- Hypovolemic: Hypovolemic POTS, or “low blood volume POTS,” is associated with abnormally low blood volume (hypovolemia). Up to 70 percent of POTS patients have lower-than-normal blood volume. Hypovolemia may occur due to gut conditions that cause excessive fluid loss, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can further contribute to low blood volume in these patients. Low blood volume can also occur due to unusually low levels of renin and aldosterone, indicating a possible issue with the body’s system for regulating blood volume.

POTS is a collection of symptoms that often appear together. It has various causes, which is why it’s considered a syndrome. Since POTS is not a disease itself, something else triggers these symptoms, but identifying the exact cause can be challenging. When doctors can’t find the cause, they call it primary or idiopathic POTS, meaning the origin is unknown.

POTS symptoms have a physical origin, but they are sometimes mistakenly attributed to psychological disorders, such as anxiety. While some people with POTS also have anxiety disorders, anxiety is not the cause of POTS.

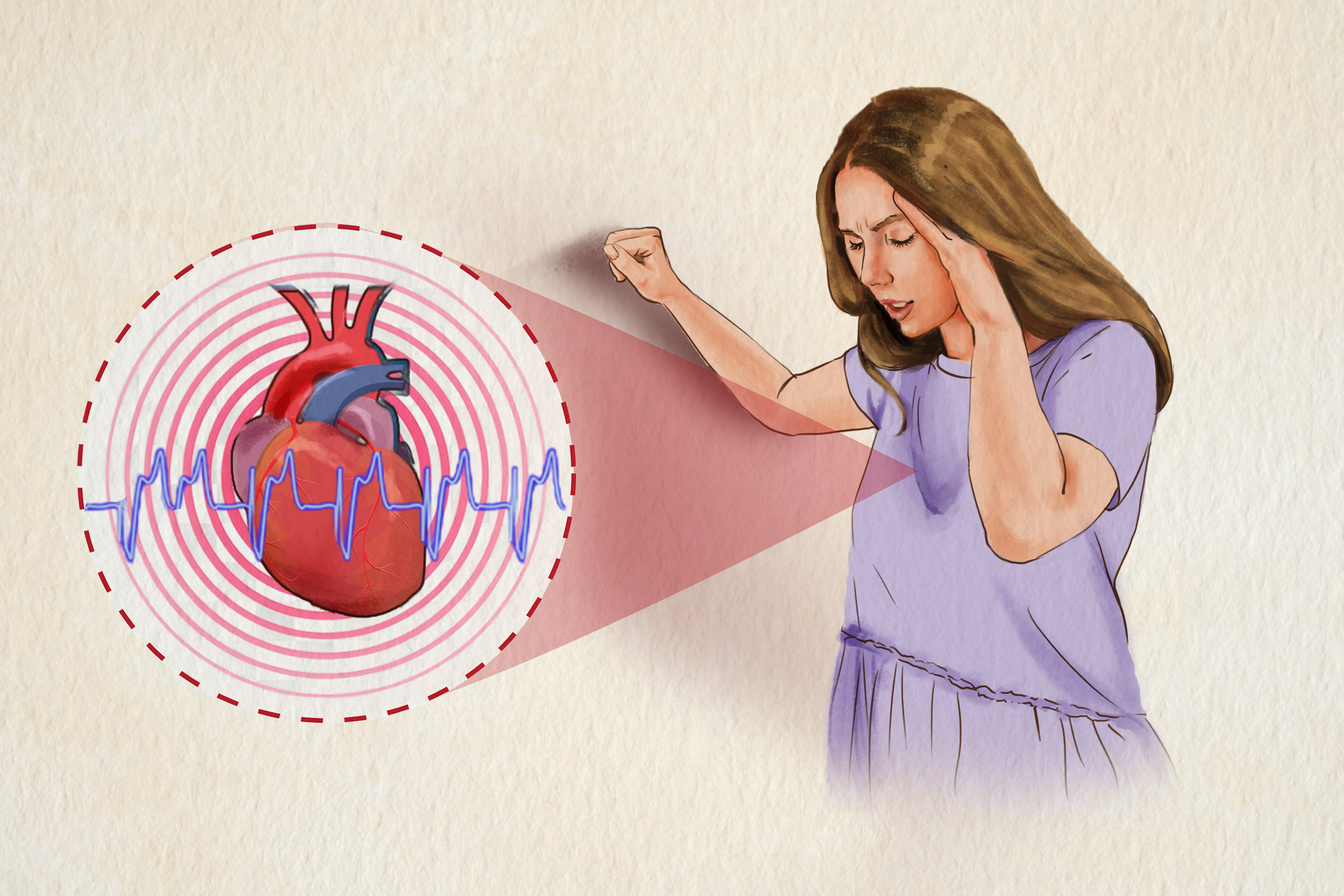

POTS results from the heart beating rapidly upon standing up from sitting or lying down. The direct cause of primary POTS is unknown, but cardiovascular deconditioning and less blood volume typically play a part. (Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

Primary POTS

Researchers have suggested various causes for primary POTS, leading to the identification of different subtypes of the condition. However, they generally agree that the main issue is an excessively fast heart rate due to poor cardiovascular conditioning.

One theory for POTS is that it might be related to autoimmune conditions, given its similarities to diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Research has found increased autoantibodies in POTS patients. Higher levels of the inflammatory marker interleukin 6 (IL-6) and other autoimmune markers have also been found in POTS patients, suggesting chronic immune system activation.

Patients with POTS often show signs of physical and cardiovascular deconditioning, though it’s unclear if this is a cause or a result of the condition. A traumatic event or illness can lead to reduced activity or bed rest, causing patients to become less fit. This results in the heart pumping less efficiently and the muscles in the limbs and abdomen weakening. Similar symptoms to POTS have been seen in healthy people in space, hinting at the role of physical fitness and gravity in POTS. People with POTS tend to have smaller hearts and less blood volume than healthy people, with a significant decrease in left ventricular mass and plasma volume.

Secondary POTS

Here are

some diseases and conditions known to cause or be associated with POTS or POTS-like symptoms in certain patients:

- Amyloidosis

- Autoimmune diseases

- Chiari malformation

- Delta storage pool deficiency

- Diabetes and prediabetes

- Multiple sclerosis

- Mitochondrial diseases

- Mast cell activation disorders

- Paraneoplastic syndrome

- Toxicity from alcoholism, chemotherapy, and heavy metal poisoning

- Vaccinations: One example is COVID-19 vaccines. According to a 2022 study involving almost 285,000 participants, there were 4,526 POTS-related diagnoses, and the risk of receiving a POTS-related diagnosis increased by 33 percent after vaccination compared to before. However, POTS occurred more frequently in individuals who had been infected with COVID-19 than in those who had received COVID-19 vaccination.

- Vitamin deficiencies/anemia: One example is iron deficiency.

COVID-19 and POTS

Various conditions, including viral or bacterial infections, can trigger POTS. Some researchers believe that COVID-19 can trigger POTS, as many people recovering from COVID-19 are experiencing symptoms such as brain fog, increased heart rate, and severe chronic fatigue. This has led doctors to test these patients for POTS. Thus far, research has found that mild and severe cases of COVID-19 can both result in POTS.

POTS is characterized by an increase of 30 or more heartbeats per minute or a heart rate of 120 or more beats per minute upon moving from lying down to standing. This can occur suddenly within 10 minutes after standing up.

In addition, POTS manifests with varying symptoms that range in severity from mild to severe, affecting individuals differently. While many experience mild to moderate symptoms that may improve with treatment or resolve on their own, approximately 25 percent of POTS patients endure severe symptoms that significantly affect their quality of life.

Some of the other most common POTS symptoms include the following:

- Dizziness and lightheadedness: With POTS, the body struggles to regulate blood pressure and heart rate properly when standing up, leading to inadequate blood flow to the brain temporarily. This can cause feelings of dizziness and lightheadedness. Prolonged sitting can cause the same symptoms.

- Severe or long-lasting fatigue: The fatigue can potentially make daily living difficult.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Shakiness.

- Excessive sweating.

- Fainting: Around 30 percent to 60 percent of individuals with POTS may experience fainting episodes. They can cause falls.

- Exercise intolerance: There’s difficulty with physical activity or a prolonged exacerbation of overall symptoms following increased activity.

- Shortness of breath.

- Cold or painful hands and feet: This is caused by issues with blood pooling or poor circulation.

- Red or purple color in the legs after standing: This condition improves with sitting or lying down.

- High or low blood pressure.

- Chest pain: Chest pain is quite common in POTS patients and may worsen when standing upright, although the exact cause remains unclear.

- Gut issues: These may include diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain. As a result, POTS may often be misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

- Visual problems: POTS patients may experience increased glare, blurred vision, or tunnel vision (i.e., the loss of peripheral vision).

Certain common symptoms may take place without standing, including:

- Headaches.

- Sweating without reason.

- Insomnia.

- Weakness.

- Brain fog: Brain fog is characterized by forgetfulness, difficulty thinking or focusing, cloudy thoughts, and trouble finding the right words. It can be triggered by fatigue, lack of sleep, prolonged standing, dehydration, and feeling faint.

- Reduced mental endurance: This symptom is due to decreased cerebral blood flow.

- Depression: This is also caused by reduced cerebral blood flow.

POTS symptoms often worsen due to:

- Warm environments: Examples include hot baths, hot rooms, or a warm day.

- Prolonged standing.

- Insufficient intake of fluids and salts: This may occur after skipping meals.

- Illnesses: The common cold or infections can exacerbate POTS symptoms. In severe cases, POTS can severely limit a patient’s ability to remain upright for more than a few minutes.

- Exercises: However, exercise is beneficial in the long term.

- Eating: Symptoms of POTS can worsen after consuming food, particularly refined carbohydrates such as sugar or white flour-based products.

- Menstruation: Some women’s symptoms worsen before their menstrual period.

- Different times of the day: Symptoms of POTS may be more pronounced in the morning, especially upon waking up.

- Alcohol consumption: Alcohol can dilate blood vessels.

- Extended periods of bed rest.

Although anyone can develop POTS, the following factors put one at a higher risk:

- Age: Most POTS patients are young, with most patients being between 20 and 40 years old. Many patients, particularly males, develop POTS during their teenage years after periods of rapid growth, and they often see symptom improvements as they get older.

- Race: Most POTS patients are white.

- Sex: Around 80 percent of those affected by POTS are female, and most are premenopausal.

- Viral or bacterial illness: Examples include mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus, Lyme disease, extra-pulmonary mycoplasma pneumonia, and hepatitis C. Some people even develop POTS after a traumatic event.

- Family history of POTS.

- Certain gene variations: For instance, the gene variation GNB3 C825T may increase the risk of POTS by causing the heart’s vagal response to withdraw more strongly in children and teens.

- Surgery.

- Giving birth: Women often develop POTS symptoms after pregnancy, and the prognosis for these symptoms tends to be less optimistic. Fortunately, newborns born to mothers with POTS appear to be as healthy as infants born to mothers without the condition. In addition, some women with POTS who become pregnant experience improved symptoms during pregnancy, likely due to the increase in blood volume that occurs after the first few weeks of gestation.

- Peripheral nerve damage.

Diagnosing POTS can be challenging because its symptoms can involve many different organ systems, and the most troubling symptom can vary significantly among individuals. As a result, patients typically experience symptoms persisting for one year or more before receiving a diagnosis.

A doctor will ask about medical history and a detailed history of orthostatic intolerance (symptoms occurring while standing upright) and conduct a comprehensive physical examination.

For POTS to be diagnosed, the following criteria must be met:

- A sustained increase in heart rate of ≥ 30 beats per minute (or ≥ 40 beats per minute for patients aged 12 to 19 years) within 10 minutes of standing up.

- No significant orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure) upon standing (a decrease of ≥ 20/10 mm Hg).

- Frequent symptoms of orthostatic (upright position) intolerance that worsen when standing up and quickly improve upon lying down. Symptoms can vary but commonly include lightheadedness, palpitations, trembling, weakness, blurred vision, and fatigue.

- Symptoms have been present for at least three months.

- No other conditions could explain sinus tachycardia (fast heart rate originating from the sinus node in the heart).

When investigating suspected POTS, doctors initially focus on ruling out heart issues, such as structural defects or irregular heart rhythms, and checking for underlying systemic problems, such as hormonal imbalances. They also review medications and assess other health issues, such as digestive problems, neurological conditions, or psychiatric symptoms, that may be linked to POTS.

Tests

During

a tilt table test, the standard method for assessing POTS, you lie on a table that tilts to an angle of 60 to 70 degrees. Throughout the test, you are secured on the table and continuously monitored for heart rate, blood pressure, and sometimes blood oxygen and exhaled carbon dioxide levels. After you lie flat for five to 20 minutes, the table is tilted upright. Although a diagnosis of POTS is typically confirmed by an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats per minute within the first 10 minutes of tilting, the test may last 10 to 45 minutes.

The following tests may be performed in addition to the tilt table test:

- Active stand test: During the active stand test, you lie down quietly for at least 10 minutes while your baseline blood pressure and heart rate are measured. Then, you stand up and remain upright without assistance for 10 minutes. Blood pressure and heart rate are measured at regular intervals (e.g., two, five, and 10 minutes) while standing.

- Valsalva maneuver: The Valsalva maneuver involves forcefully exhaling against a closed airway. It simulates various everyday activities and is used to assess how the autonomic nerves that regulate the heart respond.

- Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART): The QSART test quantitatively evaluates sweat glands controlled by small nerve fibers, assessing the function of autonomic nerves that regulate sweating.

- Imaging tests: MRI or other imaging tests may be performed to rule out tumors or other abnormalities.

- Blood tests: Blood tests such as a complete blood count assess iron levels, kidney and liver function, and thyroid function.

- Brain CT scan.

- Urine tests: People with POTS often show low urinary sodium levels, typically less than 170 millimoles per 24 hours. A series of 24-hour urine tests may be performed to check for increased levels of noradrenaline and epinephrine to exclude pheochromocytoma, a growth on the adrenal gland, as a potential cause of symptoms.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): An electrocardiogram is a painless test that shows the heart’s electrical activity and how well it is functioning. It also rules out other heart conditions that may lead to rapid heartbeats.

- Echocardiogram: An echocardiogram is a noninvasive procedure that uses sound waves to visualize the heart’s structure and function.

- 24-hour Holter monitor: A Holter monitor records all heartbeats over one day to analyze heart rate and rhythm.

The existing data on POTS complications is limited. However, common complications include:

- Depression and anxiety.

- Fatigue usually persisting beyond treatment.

- Difficulties with daily functions.

- Thromboembolism: Declining physical fitness and cardiovascular health may increase susceptibility to infections and thromboembolism.

- Trauma or injury resulting from a fall or fainting: This is the most severe complication of POTS.

POTS also has several associated comorbidities, including:

- Migraine: Migraine is arguably the most common comorbidity for POTS patients.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): This is another prevalent comorbidity for POTS.

- Vasovagal syncope.

- Fibromyalgia.

- IBS.

- Anemia.

- Type 1 diabetes.

- Lupus.

- Cardiovascular disease.

- Lesions of the autonomic nervous system.

- Syringomyelia.

- Thyroid disease.

- Certain tumors.

- Lyme disease.

- Scleroderma.

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Sarcoidosis.

- Multiple sclerosis.

- Mast cell activation syndrome.

- Joint hypermobility conditions: These include hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSD) and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS).

POTS treatment should be personalized due to varying symptoms and underlying conditions. While there is no cure, most patients can manage POTS mainly through diet, exercise, and medications, if necessary.

1. Diet

The cornerstone of POTS treatment is regular fluid intake. Typically, one should drink 64 to 80 ounces (2 to 2.5 liters) daily. In addition, increasing salt intake, either through consuming salty foods or adding more salt to meals, helps retain water in the bloodstream, thus helping more blood reach the heart and brain. POTS patients may require up to

three times the amount of salt that dietary guidelines recommend.

POTS patients, who often have digestive issues, should eat small, frequent meals that include carbohydrates with lower sugar content. This approach helps maintain stable blood sugar levels and prevents drops in blood pressure after meals.

POTS patients should avoid the following:

- Alcohol: Alcohol generally aggravates POTS by diverting blood from the body’s central circulation to the skin and thus increasing fluid loss through urination.

- Caffeinated beverages: Caffeine can cause nervousness and lightheadedness in some but may improve blood vessel constriction in others.

- Energy drinks: Energy drinks can increase heart rate and dehydrate the body, making POTS symptoms worse.

Ask your doctor or a POTS specialist to help assess the impact of diet and medications on your treatment.

2. Physical Therapy

Exercise can benefit some POTS patients but can also worsen symptoms in others. Therefore, patients should begin exercising slowly and progress based on individual tolerance. As blood circulation improves with medication and diet, exercise intensity can gradually increase to retrain the autonomic nervous system and boost blood volume.

In one 2011 study, a three-month progressive exercise regimen increased left ventricular mass by 12 percent and end-diastolic volume by 7 percent. By the end of the regimen, 53 percent (10 out of 19 that finished the regimen) of the patients no longer met the criteria for POTS.

The following exercises or therapies may be used:

- Reclined exercises: Patients unable to stand may start with horizontal or reclined exercises.

- Aquatic therapy: Aquatic therapy can be effective due to water pressure on the body.

- Manual physical therapy: This therapy addresses nerve tightness and range of motion and can help build exercise tolerance.

3. Compression Garments

Wearing compression garments and stockings may help certain POTS patients reduce excessive blood pooling in their legs. Other apparel and accessories, including inflatable abdominal binders, may also be helpful.

4. Medications

There is no single medication universally effective for POTS, and medications are not first-line treatments. They are typically reserved for severe or refractory cases to aid in stabilizing the patient for continued physical reconditioning. Currently, there are no drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for POTS. Therefore, medications should be used cautiously due to potential side effects and interactions. In addition, nonpharmacologic approaches are generally preferred and can be as effective as medications.

The following medications are sometimes used off-label to treat POTS:

- Fludrocortisone: As the primary medicine for POTS, fludrocortisone increases salt retention and blood volume. Its side effects include hypertension, low potassium levels, and headaches.

- Vasoconstrictors: For patients experiencing venous pooling, vasoconstrictors such as midodrine and ergotamine are potential treatment options. They cause blood vessels to constrict, increasing blood return to the heart.

- Clonidine and alpha-methyldopa: These medications reduce sympathetic nervous system activity, which is beneficial for POTS patients with hypertension. They can cause drowsiness, mental fog, and fatigue.

- Beta-blockers: Beta-blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol can lower heart rate when standing without major changes in blood flow, but they may also increase fatigue.

- Ivabradine: Ivabradine, a sinus node blocker, has been noted to improve symptoms in POTS patients who experience sinus tachycardia. Unlike beta-blockers, ivabradine doesn’t have side effects such as adverse effects on heart contraction strength (ionotropic effects) or blood vessel dilation.

- Pyridostigmine: Pyridostigmine increases acetylcholine levels, which can help reduce heart rate. Its side effects include muscle cramps, vomiting, and urinary issues, limiting its use.

- Erythropoietin: Erythropoietin is a treatment option for certain POTS patients with low red blood cell volume and impaired erythropoietin function or production. It helps increase red blood cell mass, thus contributing to higher blood pressure.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): These antidepressants enhance nerve activity in the standing vasoconstriction reflex, thus reducing venous blood pooling and improving orthostatic tolerance.

POTS patients should

avoid certain medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, alpha- and beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and phenothiazines.

POTS patient education should emphasize the connection between the mind and body and how factors such as anxiety, stress, and lifestyle can affect breathing patterns, thus leading to feelings of breathlessness.

A negative mindset characterized by stress or anxiety can exacerbate symptoms of POTS, such as increasing heart rate and blood pressure fluctuations. Anxiety and stress trigger the release of norepinephrine in the bloodstream. Individuals with POTS are particularly sensitive to this chemical. Moreover, the parasympathetic nervous system, which normally promotes relaxation, may also be impaired in POTS, further affecting the autonomic nervous system.

On the other hand, a positive mindset can facilitate the adoption of adaptive coping strategies, such as lifestyle and activity changes, to manage POTS symptoms effectively.

Certain natural approaches may lessen POTS symptoms. Please consult your doctor before using any of them.

1. Posture Changes

If you experience sudden faintness or dizziness, consider lying down and elevating your legs until you feel relief. If lying down isn’t an option, you can try these standing maneuvers to manage symptoms: cross your legs, rock on your toes, clench your buttocks and stomach muscles, and clench your fists.

Additionally, elevating the head of the bed helps maintain pressure in the blood vessels of the legs during sleep.

POTS prognosis varies depending on the underlying cause, with better outcomes generally seen in adolescents. For instance, approximately 50 percent of patients recover within two to five years after post-viral episodes. About half of all POTS patients recover spontaneously within one to three years.

POTS often follows a relapsing-remitting course, with symptoms fluctuating over time, leading to difficulties in employment and daily activities. However, patients in a hyperadrenergic state typically require lifelong treatment. Most individuals with POTS experience some improvement in functionality, though residual symptoms are common.

2. Supplements

- Vitamin B12: A 2013 study involving 125 children and teenagers demonstrated that youths with POTS have notably lower levels of B12 deficiency. Therefore, B12 supplements may help alleviate orthostatic symptoms in this group.

- Vitamin B1: A 2017 study found that a small number of POTS patients might experience vitamin B1 deficiency. Twenty-five percent of the vitamin B1-deficient patients experienced significantly improved POTS symptoms after taking oral vitamin B1 supplements. The study recommended addressing vitamin B1 deficiency to help manage POTS symptoms effectively.

- Iron: POTS is associated with low iron stores and mild anemia, suggesting that iron deficiency may contribute to the condition’s development. Thus, iron supplementation may help improve the symptoms of some POTS patients.

- Carnitine and coenzyme Q10: Taking a daily supplement of 250 milligrams of carnitine and 100 milligrams of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) can help alleviate symptoms of general muscle weakness and fibromyalgia. Carnitine is a naturally occurring compound in the body that helps with fatty acid metabolism. CoQ10 is a natural compound found in the mitochondria of cells. It plays a critical role in the production of energy (ATP) within cells and possesses potent cardiovascular protective properties.

3. Cough Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Cough cardiopulmonary resuscitation is a technique in which a person experiencing a heart attack or certain types of

cardiac arrhythmias can potentially maintain some level of circulation to the brain and other vital organs by forcefully coughing at regular intervals. It can prevent loss of consciousness when a patient feels dizzy in an upright position, thus providing a temporary measure.

4. Skin Surface Cooling

Since a warm environment can exacerbate POTS symptoms, cooling the entire body helps patients handle standing up better, especially if they’ve been overheated or are recovering from long periods of bed rest. This works effectively by reducing blood flow to the skin, which keeps more blood in essential areas such as the heart and brain.

While cooling the entire body isn’t easy in daily life, cooling specific surface areas such as the face, neck, or chest can help manage acute symptoms for POTS patients in hot weather. Here are some tips:

- Cold water spray: Keep a spray bottle of cold water in the fridge and spray water on your face when needed.

- Cooling towels: Wrap a cooling towel around your neck.

- Cooling vests: A cooling vest keeps your body cooler and reduces symptoms such as dizziness.

- Portable fans with mist: A small fan that sprays cool mist helps circulate cool air around you.

5. Acupuncture

A

2013 study showed that

electroacupuncture, a novel form of acupuncture in which a small electric current is passed between pairs of acupuncture needles at the

Neiguan (PC-6) acupuncture point, improved orthostatic tolerance by enhancing cardiac function and activating the sympathetic nervous system. Thus, electroacupuncture showed promise in effectively managing orthostatic intolerance.

It’s impossible to prevent POTS, as its exact causes are not always clear and can vary from person to person. However, there are steps you can take to help reduce the risk of developing POTS and preventing episodes, including:

- Avoiding prolonged standing.

- After lying down, sitting for a moment before standing up quickly.

- Avoiding or limiting caffeine and alcohol.

- Identifying specific triggers of POTS episodes.

- Avoiding triggers: Examples may include skipping meals, not getting enough sleep, taking hot baths or saunas, and consuming high-carbohydrate meals.

- Staying hydrated.

- Managing stress.

- Changing postures: If you sit for extended periods, try crossing your legs and bringing your knees up.

- Drinking sports beverages: Drink electrolyte beverages when it’s hot or before participating in sports to replenish fluids and minerals lost through sweating. However, making your own beverages with high-quality electrolyte tablets rather than drinking store-bought ones is best, as they contain a lot of sugar.