In Alzheimer’s disease, brain cells lose the ability to break down sugar stores, which may drive disease progression, a recent study found.

The study, conducted in flies and human brain cells, found that dietary fasting slowed disease progression and may explain why drugs and lifestyle habits that reduce caloric intake also reduce the risk of dementia.

“This discovery adds a new layer to our understanding of Alzheimer’s—one that links metabolism more directly to neurodegeneration,” Dr. Achillefs Ntranos, a board-certified neurologist who was not involved in the study, told The Epoch Times.

The Brain’s Sugar Storage System

The study, published in Nature Metabolism, found that breaking down stored glucose in neurons could help prevent toxic protein buildup and brain cell damage.

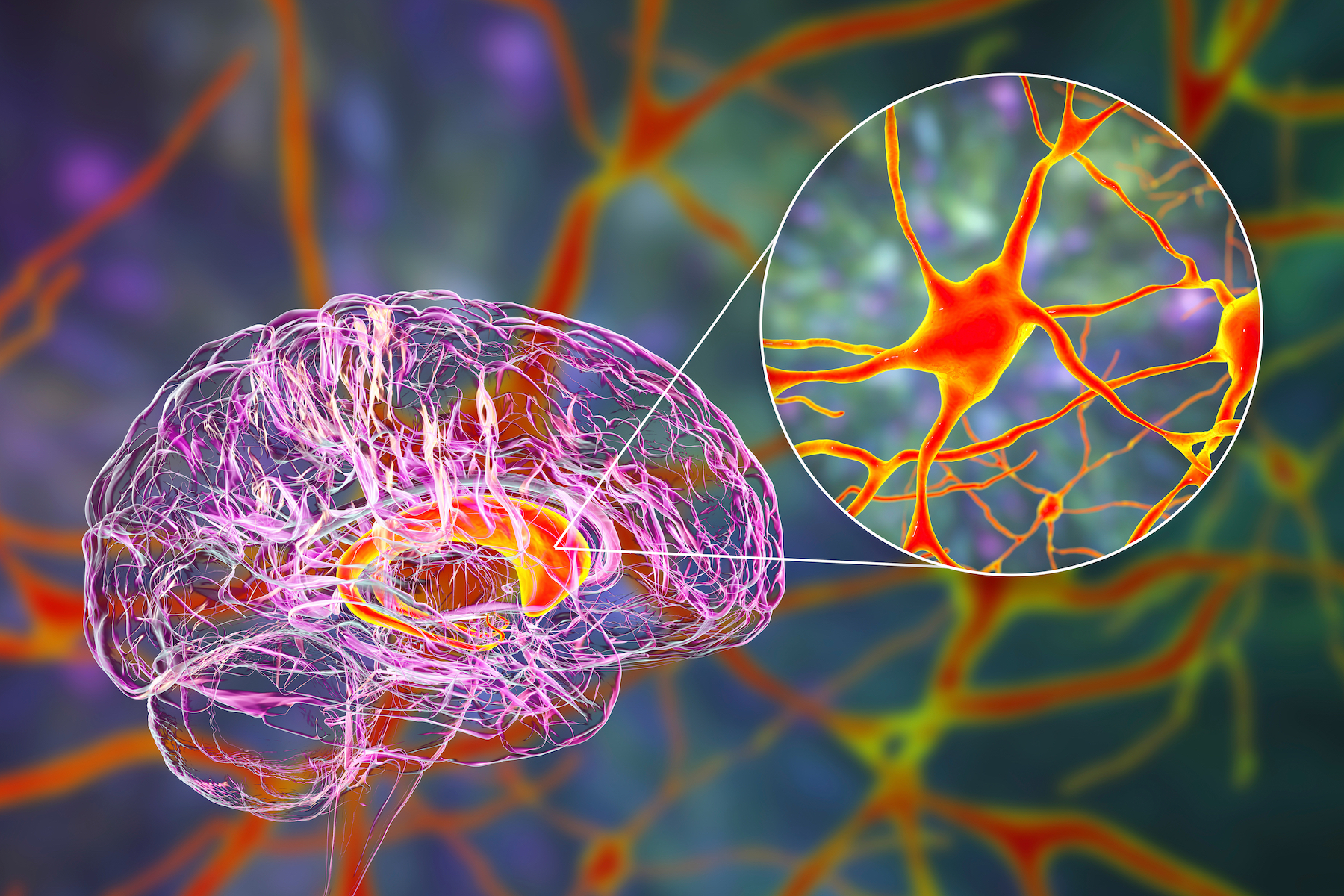

Researchers at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging focused on glycogen, a form of stored sugar, typically considered an energy reserve found in the liver and muscles. While small amounts of glycogen are found in the brain to support certain cells, its accumulation may drive brain disease.

The research team, led by postdoctoral researcher Sudipta Bar, found that neurons accumulate too much glycogen in Alzheimer’s disease. The buildup was observed in both fruit fly and human cells. This accumulation appears to drive brain disease, with tau protein—which plays a role in the development of Alzheimer’s—physically binding to glycogen, trapping it and preventing its breakdown.

“Stored glycogen doesn’t just sit there in the brain; it is involved in pathology,” study senior scientist and professor Pankaj Kapahi said in a statement.

Sugar Processing and Neuron Damage

When glycogen becomes trapped and can’t be broken down, neurons lose an important way to handle oxidative stress—a damaging process involved in aging and brain diseases.

Glycogen in the brain is broken down into antioxidant molecules such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and glutathione, which both help protect cells against oxidative stress.

By restoring the activity of an enzyme called glycogen phosphorylase (GlyP), which initiates glycogen breakdown, tau-related damage in both fruit flies and human neurons was reduced.

Significantly reducing calorie intake through dietary fasting naturally increased GlyP activity in flies and improved outcomes in flies with tau-related disease. Researchers also mimicked this effect using a synthetic drug.

This finding may explain why glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) drugs—now widely used for weight loss—show promise against dementia by potentially mimicking the effects of dietary restriction, Kapahi noted.

“If neurons can’t properly break down sugar, they may become energy-deprived and vulnerable to dysfunction or death, which gives us a new angle on why neurodegeneration happens in the first place,” said Dr. Luke Barr, a board-certified neurologist and chief medical officer at SensIQ Nootropics + Adaptogens, who was also not involved in the study.

“It opens up a new area of research that connects metabolic dysfunction directly to brain aging,” he added.

Practical Applications

The research suggests more feasible approaches may be within reach. Dr. Ryan Sultan, a dual board-certified adult and child psychiatrist affiliated with Columbia University and NewYork-Presbyterian, cautioned that although caloric restriction showed benefits in the study, it could pose risks—especially as weight loss and poor nutrition are already common in advanced neurodegenerative diseases.

Dr. Kimberly Idoko, a board-certified neurologist and medical director at Everwell Neuro, who was not involved in the study, noted that GLP-1s—used to improve insulin sensitivity to enhance the breakdown of sugars—theoretically may have effects such as reducing neuroinflammation.

“Their long-term risks, including to brain health, are still being assessed,” Idoko said. “So we’re probably not near the point of prescribing metabolic drugs as a primary prevention strategy for Alzheimer’s.”

Studies have linked being prescribed GLP-1 drugs to reduced risks of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, though the mechanism is still unclear.

More feasible approaches, such as intermittent fasting or optimized diets, could be a good middle ground, Ntranos said.

He said that intermittent fasting approaches—such as time-restricted eating or a 5:2 diet—may be easier for some people to follow and offer metabolic benefits that support brain health. Ntranos added that even without strict fasting, maintaining a nutritious, antioxidant-rich diet is already encouraged for promoting overall cognitive well-being.

“I suspect that in the future we’ll see personalized diet plans as part of dementia prevention or care,” he said. “Perhaps not extreme fasting for everyone, but moderate dietary changes that mimic those beneficial effects.”

Looking Forward

The discovery of glycogen metabolism as an unexpected protector against neurodegenerative disease opens new directions for developing therapies for Alzheimer’s disease, Kapahi said.

Researchers confirmed similar glycogen buildup and the protective effects of glycogen phosphorylase—the enzyme that breaks down glycogen—in human neurons from patients diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, pointing to potential new treatments based on this discovery.

“By discovering how neurons manage sugar, we may have unearthed a novel therapeutic strategy—one that targets the cell’s inner chemistry to fight age-related decline,” he said.

Kapahi added that findings like these offer hope that better understanding—and perhaps rebalancing—our brain’s “hidden” sugar code could unlock powerful tools for combating dementia.