Three children grew up in the same household, raised by the same parents, exposed to the same environment. Yet their lives unfolded in dramatically different ways—all because of a single gene.

The older brother met all of his early developmental milestones and could read at the age of 5. He had an excellent memory for car license plates and could make rapid mental calculations. His social deficits, however, came to light once he started school. He was socially awkward, had few friends, couldn’t understand social cues, and was prone to mood swings. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, which is under the autism spectrum disorder label.

His younger brother developed typically, showing no signs of autism or other developmental challenges.

The younger sister, however, developed autism with intellectual disability. As an infant, she met early motor milestones but had very delayed language development. She had to leave school at the age of 7 and instead attended a hospital program during the day. At age 12, her intelligence scores were similar to those of a child under 6 years old, and though she could speak a little, she often had pronunciation errors. She exhibited self-injurious behaviors such as hitting her head and also experienced nighttime bedwetting.

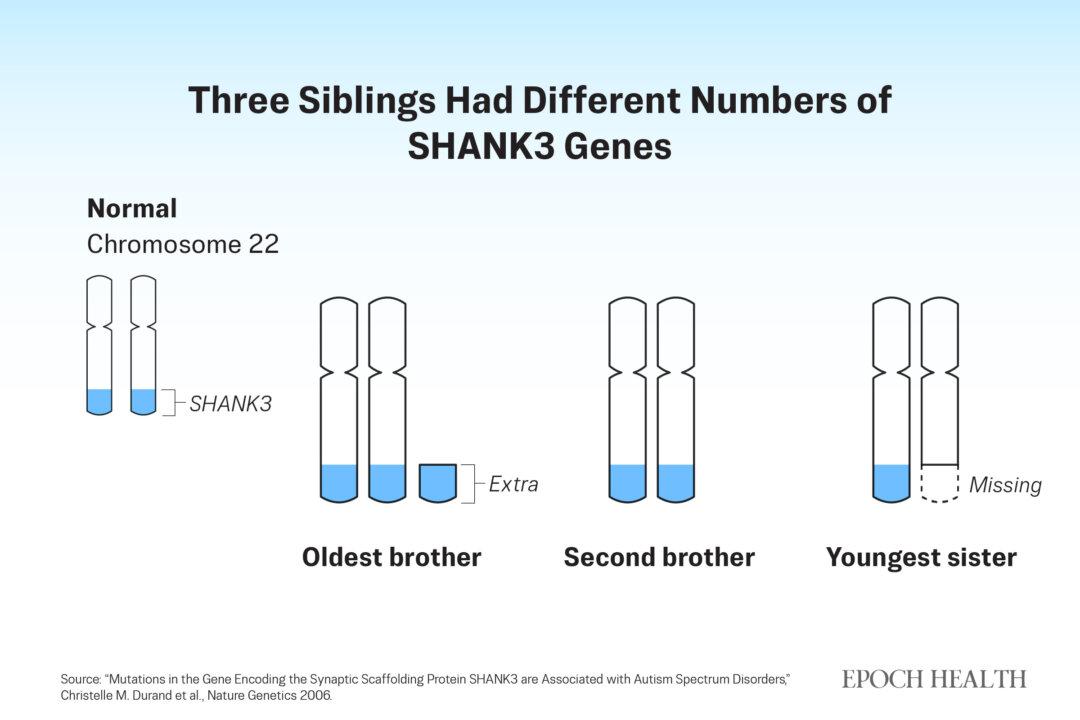

The key difference between each child’s behaviors was the number of copies of an inherited gene called SHANK3 they each had.

This unique case was discovered by French researchers. The family’s unique inheritance pattern gives a glimpse into autism’s complex genetic landscape.

Joseph Buxbaum, director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, told The Epoch Times that autism has a strong genetic component. However, on the surface, the relationship between autism and a person’s genetics is not always clear-cut.

Two Main Genetic Drivers

Two major gene types drive autism—de novo mutations and polygenic variations.

De novo mutations are new genetic changes that occur spontaneously in the egg or sperm and are not inherited from a parent. Most of the genetic research has been focused on finding de novo mutations. They are rare and only drive a smaller proportion of autism cases, but tend to have a strong effect on their carriers. A single de novo variation may be enough to cause autism, and the child is more likely to have debilitating autistic characteristics, such as lower IQ and the need for more caretaking.

Polygenic variations are far more common drivers of autism, accounting for up to 50 percent of all autism cases. However, they are usually harder to detect, since inherited gene variation often involves hundreds to thousands of genes, with each contributing a tiny effect.

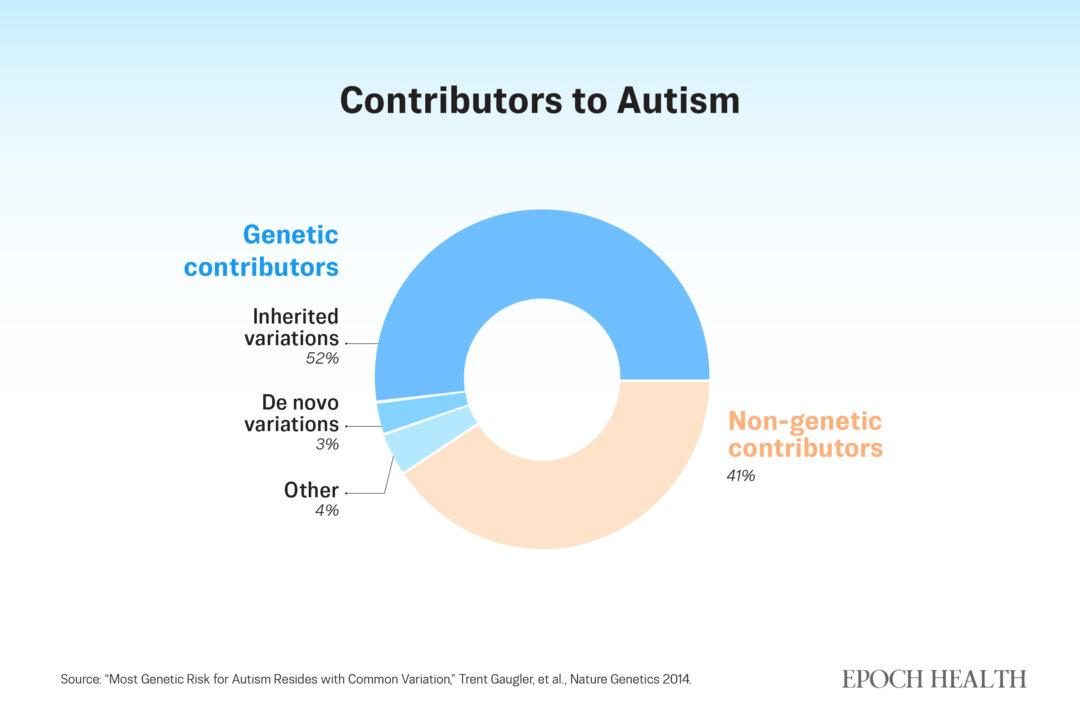

Research estimates that genes are the cause of around 60 percent of autism cases. (The Epoch Times)

Buxbaum, co-founder of the Autism Sequencing Consortium, an international group of scientists who share autism samples and data, compared the subtle effects of inherited genes on a person’s risk of autism to the way genes influence a person’s height: “I have some common variants for short height, but I’m six-five, right?”

Not everyone who inherits genetic variants that are linked to autism will necessarily develop autism, as it is dependent on the person’s entire genetic makeup. The complexity of different genes working against and with each other is why inherited autism genetics can be so puzzling.

The pattern of autism in families often provides clues about which type of genetics is at play. When only one child in a family has autism, de novo mutations are the likely culprit. When multiple children are affected, inherited variations are usually responsible.

Specific Genes

More than a hundred genes have been strongly linked to an increased risk of autism.

These genes are involved in brain cell formation, maturation, and their communication. The SHANK3 gene helps form the proteins involved in the connection points between neurons. When these connections don’t form properly—whether from having too few or too many SHANK3 copies—it can alter communication between brain cells.

SHANK3 gene resides in chromosome 22. In the story involving the three children, the typically developing brother had the standard two normal gene copies. The older brother with mild autism inherited an extra piece of chromosome 22, in addition to two normal copies. The sister with severe autism had only one normal copy, due to a missing piece of chromosome 22.

Three siblings had different amounts of genetic material on chromosome 22. (The Epoch Times)

Another example is the CHD8 gene, which regulates how DNA is packaged within cells, influencing whether certain genes are activated. When a mutation occurs in CHD8, it can prevent genes necessary for development from being activated. Defects in this gene have been linked to problems with brain cell growth.

Some autism genes work more indirectly. For example, the genetic condition phenylketonuria causes the child to be unable to break down the amino acid phenylalanine. Children with such conditions who eat foods containing phenylalanine can develop toxic levels that harm brain development, potentially causing autism-like symptoms.

Environmental factors also influence genetic risk. While everyone will accumulate some de novo mutations in their lifetime, older people, smokers, and those who are exposed to radiation and toxic chemicals have a higher risk of forming more. As parents get older, the risk of having a child with autism increases since they tend to accumulate more de novo mutations in their eggs and sperm.

Severe Autism May Be Treatable

Knowing an autistic person’s genetic deficits makes treatment possible. Researchers have found that some of the debilitating autism symptoms can be reduced or even reversed.

“When we look at individuals with autism and a significant cognitive impairment, the likelihood of identifying the underlying cause by applying whole genome sequencing is around 30 to 35 percent,” Dr. Christian Schaaf, medical director of the Institute of Human Genetics at Heidelberg University, and discoverer of Schaaf-Yang syndrome, told The Epoch Times.

“If we take individuals with high-functioning autism and no cognitive impairment, the likelihood of identifying the underlying cause is less than 10 percent.”

Genetic studies are therefore more helpful to children with severe autism accompanied by intellectual disability than those who need less support, Schaaf said.

The idea of treating autistic people can be controversial, especially among some members of the neurodiversity movement, who see treating autism as an elimination of their autistic characteristics, which are integral to their identity.

However, people who are cognitively sound and capable of self-advocacy are not the target patients in medical autism treatment. These medical interventions are also not made to eliminate their neurodiversity.

Rather, treating autism is meant to make the profound autism patients’ life easier, Buxbaum said.

“It’s useful to always make it clear that autism is this incredibly, ridiculously wide spectrum, and when we talk about treatment and gene-targeted therapy, we’re only talking about profound autism,” Buxbaum said.

“If somebody is on the spectrum, but has a little bit of trouble with job interviews because they don’t attend to the social skills so well, we can give them a job class to help them do better—they don’t need gene-targeted therapy.”

Gene-targeted therapies take several approaches. The most well-known involves changing a person’s genetic code. These therapeutics are controversial and, in rare cases, can present the risk of introducing negative genetic changes and thus potentially new genetic problems.

There are other, more conservative therapeutics.

If a child has one faulty gene and one healthy gene, doctors might use medication to make the healthy gene more active, which can help counteract the effects of the defective one. Such an approach isn’t always possible, especially if the gene is difficult to target or if many genes are involved.

Alternatively, researchers may give drugs or supplements to fix adverse downstream effects. For instance, if a certain deficit causes the body to become deficient in a key nutrient, and the normal gene cannot be targeted, the nutrient deficiency can be corrected by supplementing the patient with the missing nutrient.

Schaaf’s team demonstrated this principle with a 4-year-old boy who was regressing from his developmental milestones. He was losing speech and was aggressive and agitated. Biochemical and genetic testing showed that the boy had a mutation in the TMLHE gene, which had caused severe carnitine deficiency.

By supplementing the child with carnitine, his regression ended, his language skills improved, and he became calmer.

Other Similar Conditions

Genetically inherited conditions have traditionally been thought to be lifelong, but emerging research may change this long-standing notion.

One ongoing clinical trial involves Angelman syndrome, which causes developmental delays and is often linked with autism. It is primarily caused by a defect or missing UBE3A gene inherited from the mother.

A healthy child inherits two copies of the UBE3A gene, one from each parent. However, in Angelman syndrome, during brain development, the father’s copy of the gene switches off. Therefore, if the child’s mother’s copy of the UBE3A gene is faulty or absent, it results in abnormal brain development and Angelman syndrome.

The trial on Angelman, which is still in progress, aims to treat Angelman syndrome by introducing proteins that turn on the paternal copy of the UBE3A gene. Preliminary results show that children who had the UBE3A gene turned on have demonstrated significant improvements.

“The biggest thing is, they saw evidence for improvements in cognition, in language, and in daily living skills,” Buxbaum said. Improvements in cognition and language are critical for children’s survival and are the reason why many children with autism and intellectual disabilities will need care for life, he added.

Similarly, another trial in men with Fragile X syndrome also showed improvements in cognition. People with Fragile X syndrome experience developmental delays, including learning disabilities, due to insufficient levels of a brain signaling molecule called cAMP. Researchers found that raising cAMP levels improved adult participants’ cognition and behavior.

“If these trials and a couple of other trials see real, positive changes, everybody will start thinking about these kinds of disorders as being tractable to therapy,” Buxbaum said.

Not the Whole Picture

Not all people with autism will necessarily have an “easy” genetic variation that can be addressed. Most people with autism have hundreds or even thousands of gene variants.

Buxbaum believes that with more research, scientists may be able to identify the major neurobiological pathways that drive autism. Therefore, it may be unnecessary to find every single genetic variant.

If the key pathways can be identified, those pathways could be targeted rather than intervening at the genetic level.

However, genetics alone does not tell the full story of autism. Research estimates that genes are responsible for around 60 percent of autism cases.

Some of the missing 40 percent may be due to calculation errors and insufficient sample size to detect new variations, but another potential reason is the environment.

From the 1980s to today, the prevalence of autism has risen sharply from about 0.06 percent to 3.2 percent.

Some of this rise can be explained by better diagnostic criteria and maybe even overestimation of current autism rates, but not all. The most severe cases—profound autism—have increased by about 70 percent from the year 2000s to 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s data.

“When rates have gone up so much, it’s not changes in gene frequency, so there must be something environmental or diagnostic that’s presumably happening now,” Neil Risch, director of the Institute for Human Genetics at the University of California–San Francisco, told The Epoch Times.

Even among identical twins, who share the same genetics, there are pairs in which one has autism and the other does not, indicating environmental influences, Risch said.

“The assumption in twin studies is that the amount of environmental sharing between identical and fraternal twins is the same, which may not be the case,,” he added.

In the womb, each twin is on a different side, which may lead to different environmental exposures in utero—perhaps one twin receives more nutrients than the other.

The science is still young.

Like the parable of the blind men and the elephant, focusing solely on genetics reveals only part of autism’s story. Beyond the genetic blueprint, environmental factors, developmental timing, and individual biology also play roles—topics that will be explored in the following series.