Unlike depression or anxiety, autism is not classified as a mental illness. It is a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Autism’s distinction as a neurodevelopmental disorder sets it apart in terms of treatment and potential for improvement compared to other psychiatric conditions.

“In autism, kids can go from being quite significantly developmentally delayed on developmental tests to functioning in the normal range,” Dr. Fred Volkmar, a professor emeritus at the Yale School of Medicine specializing in child psychiatry, pediatrics, and psychology, told The Epoch Times.

A Neurodevelopmental Disorder

Neurodevelopmental disorders refer to conditions that typically manifest in early childhood and impair natural development.

The term “neurodevelopmental disorders” is often used interchangeably with “childhood-onset disorders,” said Volkmar. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is another neurodevelopmental disorder many are familiar with.

Autism typically occurs within the first one to three years of life. Though children with milder symptoms may often be diagnosed a few years later.

Mental disorders such as depression and anxiety can occur at anytime in life.

However, having a neurodevelopmental disability can increase a person’s risks of developing mental disorders as they grow older, with 40 to 50 percent of autistic people experiencing depression and anxiety, respectively, at some point in their lives.

People with neurodevelopmental disorders struggle with learning and performing social, cognitive, and/or physical tasks.

In the case of autism, a core difficulty lies in social interaction, with symptoms typically manifesting by 6 to 24 months of age.

“In typical development, social interest and social focusing on other people is a very core feature of development,” psychologist Deborah Fein at the University of Connecticut, who specializes in understanding and treating autism spectrum disorders, told The Epoch Times.

Those with autism often struggle to understand social cues and maintain conversations and relationships. In connection with these social challenges, some autistic children also have language delays and difficulties speaking.

Another defining feature is difficulty adapting to change, which manifests as repetitive behaviors and rigid routines.

What causes these difficulties?

A Mix of Factors

There is generally an assumed brain basis for all neurodevelopmental disorders.

Early research in the 1970s suggested that children with autism exhibited distinct EEG patterns, supporting the theory that autism is rooted in altered brain function. Later, postmortem studies have also shown different brain anatomical structures between autistic and typically developed people.

Around the same time, twin studies began to reveal a strong genetic component.

If one identical twin has autism, there is a 60 to 90 percent chance the other will as well, compared to just 5 to 40 percent for non-identical twins.

Identical twins are more likely than fraternal twins to both develop autism. (The Epoch Times)

Autism cannot be traced to a single gene. Researchers estimate 500 to 1,000 genes may potentially be associated with autism. Up to 10 percent of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder also have a known genetic syndrome, such as Down syndrome or cerebral palsy. For the remaining 90 percent, more than half can be traced to a genetic basis, while the other 40 percent remains unaccounted for.

Unaccounted cases may be due to metabolic conditions like mitochondrial dysfunction. Environmental factors—such as pregnancy complications and postnatal factors like insufficient social connections, early life infections, and chemicals—may also increase autism risk.

Therefore, autism appears to result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and neurological factors. “So you could say [it is a] neuro-genetic developmental disorder,” Volkmar said.

Still, the prevailing theory holds that autism has a strong genetic component. As a result, it has long been considered a lifelong condition.

However, that may not always be the case.

Outgrowing Autism

Some children can make significant progress—especially with early behavioral intervention before the age of three. A small percentage of children may eventually lose their diagnosis, according to Volkmar.

“There’s research on kids who outgrow their autism,” Volkmar said, “They technically no longer meet the criteria for autism, but they often still have residual symptoms.”

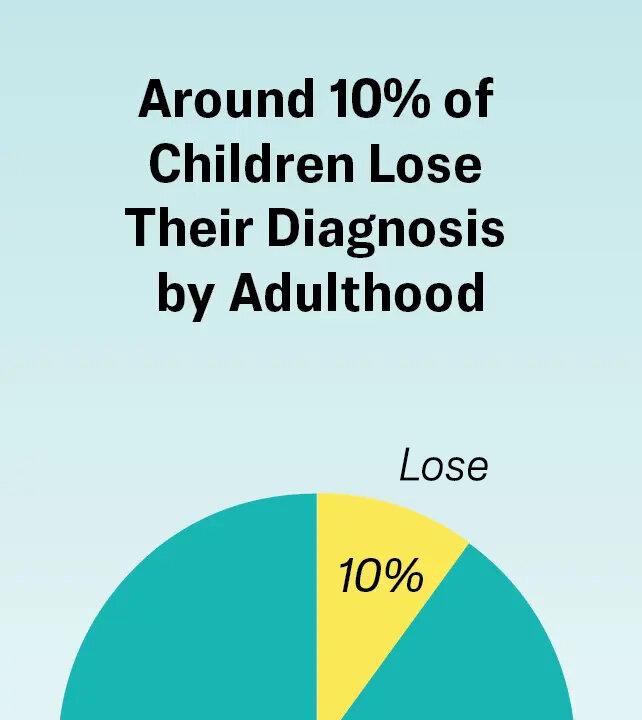

(The Epoch Times)

Brains are most neuroplastic in the first three years of life, and by training a child to surpass their social difficulties, they may grow up to be socially functional and no longer considered autistic, Fein said.

Studies suggest that approximately 10 percent of children with autism may no longer meet the diagnostic criteria by adulthood.

Fein has conducted research showing that certain early traits may predict treatment success. Children with higher IQs, stronger language abilities, and the capacity for mimicry play—combined with early diagnosis and intervention—are more likely to lose their diagnosis.

It’s worth noting that these children are cognitively sound and therefore have a milder form of autism than profound autism, the most severe type. We’ll discuss this further in the following article.

The most common type of treatment for autism is applied behavioral analysis, a behavioral therapy that teaches children social skills, such as maintaining eye contact and verbally expressing their desires. It is widely considered the gold standard for autism treatment.

However, children who lose their diagnosis do not necessarily become the same as typically developing children.

Fein has observed that many of these children later develop other issues, such as attention problems or ADHD.

A possible explanation is that difficulties with attention are a key part of autism, even though it’s not a diagnostic criterion, Fein said. Therefore, once a child becomes more socially adept and moves off the autistic spectrum, the other disabilities in attention and focus become more apparent and give a picture of ADHD instead.

In a follow-up brain imaging study, Fein and her colleagues found that children who had lost their autism diagnosis later in life had brains more similar to those who retained the autism label, compared to those of typically developing children.

Children who lost their diagnosis also had unique brain activity not seen in other groups, suggesting their brains had to form new pathways to learn and adapt.

Still, even if the autism label no longer applies, adults who grow up with autism may retain certain quirks. They may use overly formal language that is not typically used in everyday speech, such as “excited by this new phenomenon,” and sometimes coin new words, like “electronical wires,” rather than “electric wires.” As adults, they also are partial to routines, Fein said.

Since children who grew up with an autism diagnosis are often put through behavioral training, they also follow social etiquette more closely and, as a result, tend to get ranked as being more likable than typically developing children, Fein said.

Fein illustrates how people with autism tend to follow social etiquette with a dialogue from the TV show “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” in which detectives are questioning an autistic person:

“He’s [the autistic person] looking at the detective, and ... says something like, ‘Oh, I have to look away, because if I look at you more than two-thirds of the time I look aggressive, and if I look at you less than one-third of the time I look evasive.’ He’s learned that rule.”

In addition to behavioral therapies, some doctors believe that autism may be treated based on its underlying biomedical causes—such as immunological differences, vitamin deficiencies, mitochondrial dysfunction, and more.

For example, neurologist Dr. Richard Frye’s research has shown that some children produce antibodies that interfere with nutrient absorption. When those nutrients are restored, improvements in focus and language can follow, he told The Epoch Times.

Internal medicine physician Dr. Armen Nikogosian told The Epoch Times that children who receive biomedical therapies at a younger age, such as less than five years old, may experience great improvements in their behavior. Children who receive treatments later on in life typically see milder improvements.

The early developmental window offers some children with autism—often regarded as a permanent disability—the chance to achieve meaningful and lasting improvements in their lives.