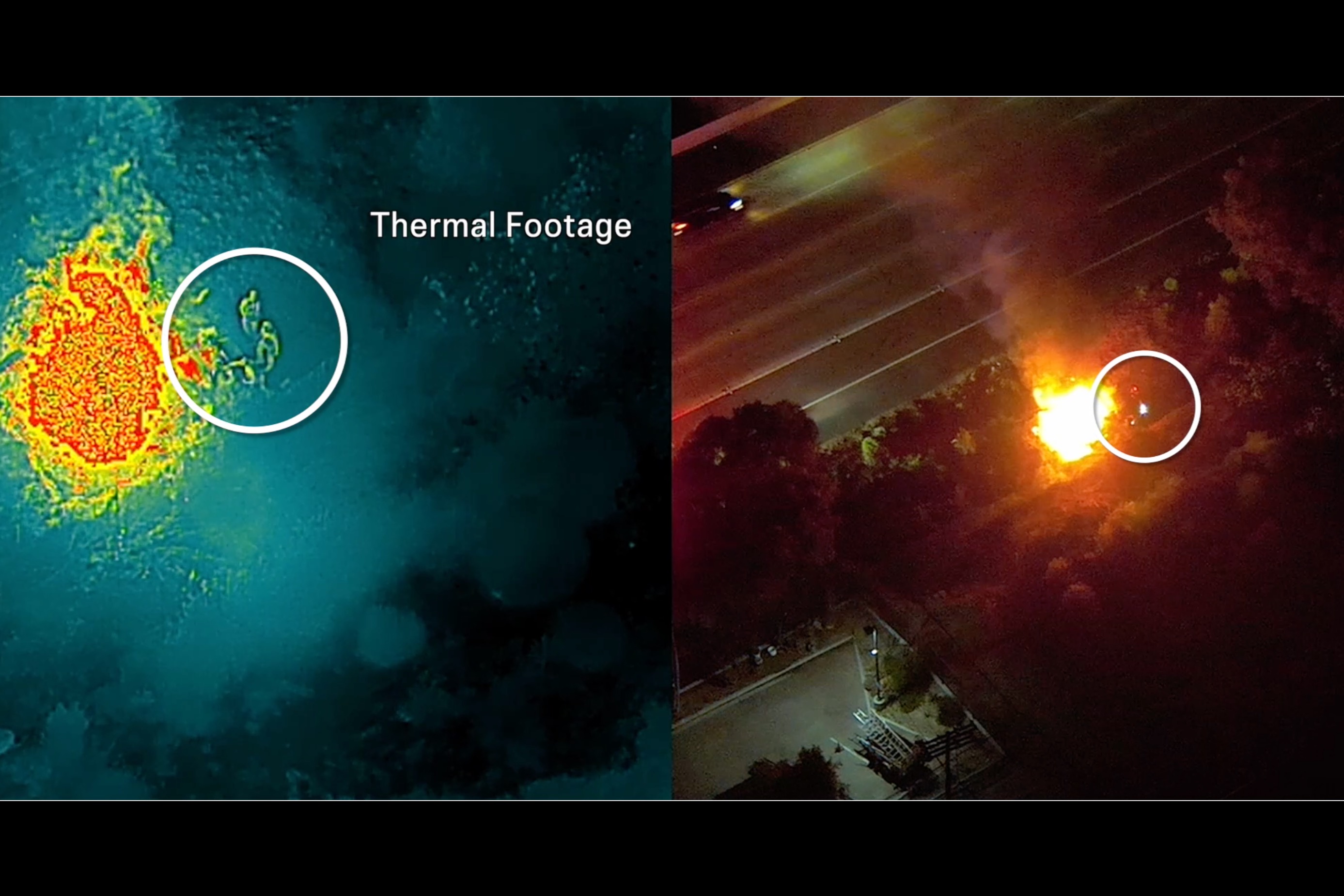

Drone footage from the Chula Vista Police Department during a rescue operation. (Edited by The Epoch Times, Chula Vista Police Department)

CHULA VISTA, Calif.—The scene that unfolded along Interstate 5 looked like a carefully choreographed action film sequence. But it was a real life-or-death situation.

Flames and smoke billowed into the night sky from a vehicle that had crashed off the roadway. Upon arrival, police discovered that the car’s driver was trapped inside, screaming in agony.

“C’mon, give me your hand!” an officer yelled, as he and three others worked frantically to extricate the man through a rear window they had broken.

Panting and grunting, the officers struggled. Then, seconds after they pulled the man to safety along the highway’s berm, the car exploded. A ball of fire engulfed it just as a fire truck arrived.

The Hollywood-worthy timing, captured in video footage, is breathtaking.

Chula Vista Police Capt. John English said the man “probably would have perished” were it not for the officers’ heroism, as well as the aid of a camera-equipped, airborne drone.

By relaying real-time information to officers as they head to emergencies such as this one, drones help police plan their actions.

English reviewed video footage of the fiery rescue with The Epoch Times, explaining how a drone helped officers save the man’s life.

As the car burned, the drone’s aerial view allowed police to quickly identify the best route to the scene. Without that perspective, officers easily could have chosen a more distant highway entrance.

“That would have taken extra time to get there, and they didn’t have it,” English said.

Also, because the drone’s thermal imaging showed no person near the burning car, officers suspected that someone might still be inside the wreckage. That fear increased their sense of urgency, helping to avert tragedy.

Although the man and three of the four rescuing officers were hurt, all recovered. That incident, on Oct. 13, 2023, stands out as a dramatic example of how drones are bolstering police work across the nation.

Officers have used terms such as “game changer,” “transformational,” and “revolutionary” to describe the effect of drones on their jobs.

Others are raising alarms over this technology’s capability to be intrusive.

In Eureka in northern California, a city of about 25,000 people, opponents recently stopped local police from even looking into a drone program.

The city’s police had relied on outside agencies for drone assistance for several missions, including locating armed suspects near school campuses and negotiating with a suicidal person who threatened to leap from the city water tower. Lacking a local drone fleet “can limit timely access to this critical resource,” officials said, explaining the reason for the proposed study.

After citizens pressured city leaders to back away from the idea, the city announced that the proposed drone study had been cut from the city council’s Oct. 21 agenda.

An opposition group, which declared victory on its website, stated that it expects the city to resurrect the proposal.

“We vow to keep fighting surveillance overreach ... [to] preserve our integrity, safety, and privacy in our rapidly changing world,” it stated.

According to advocates, police already are following standard procedures that safeguard people’s privacy while greatly enhancing public safety. They consider drones a crucial asset at a time when many police agencies are understaffed and underfunded.

From Rescues to Arrests

In the seven years since the Chula Vista Police Department pioneered using drones as first responders, increasing numbers of police and fire agencies have adopted the technology.

Some departments, including Chula Vista’s, still use advanced, affordable drones from DJI. This is a source of security concerns because the company is based in China, which has a history of stealing U.S. technology and data.

The Chula Vista Police Department stated that its devices have always operated with U.S.-based software “to bypass the drone manufacturer’s systems.” Data from the drones are encrypted and stored on U.S.-based servers “that meet federal requirements for confidential law enforcement databases,” the department’s website states.

Skydio, a U.S. company, supplies drones to 800 public safety agencies, including those in New York City, where police are using the aircraft to quell the dangerous trend of riding on top of subways, known as “subway surfing.”

In Cincinnati, which is situated along the Ohio River, police used a drone to track a felony suspect who jumped into the water and tried to swim away.

In Redmond, Washington, officers used a drone to reveal the hidden location of a missing elderly man with dementia. He was found safe, sitting in a wooded area.

A police officer monitors a drone flight near the Chula Vista Police Department in Chula Vista, Calif., on Aug. 21, 2025. Drone use for first response is spreading nationwide, although some critics cite surveillance overreach and data security risks, especially with Chinese-made models. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Police in all three cities run drone first-response programs. Drones go airborne to relay and record live video footage from scenes where people have reported disturbances or circumstances that appear to imperil lives, safety, or property.

Across the United States, officers credit drones with improving police safety and efficiency. Drones also help police rescue people, de-escalate contentious situations, and arrest suspects.

“We hear more and more reports from our customers about people actually surrendering to drones,” Skydio CEO Adam Bry said at a 2024 conference in California.

His audience had just watched a staged, live demonstration of a remote police officer using a drone to track a fleeing suspect. Using the drone’s loudspeaker, the officer ordered him to put his hands up and walk toward on-scene police.

“[Such an outcome] is not far-fetched at all,” Bry said.

Chula Vista Laid Groundwork

Jon Beal, CEO of the Law Enforcement Drone Association, said he expects the drone first responder trend to grow rapidly, largely because of “trailblazers” such as Chula Vista.

That department’s leaders “stuck their necks out” to figure out drone methods that are now being replicated across the nation, he said, noting that departments fine-tune policies to meet each community’s needs.

Over the years, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has been removing approval obstacles.

And President Donald Trump’s June executive order supporting expansion of drone use in the United States further aims to streamline the administration’s processes for drones.

It builds on a directive he issued during his first presidency, ordering agencies to update regulations for “unmanned aircraft systems”—the technical term for drones and their related equipment—while ensuring safe operations. The goal is to spur drone use in sectors ranging from agriculture to commerce to emergency management.

Police Officer Ben Miller pilots a drone and monitors the scene its camera reveals at the Cincinnati Police headquarters in Cincinnati on Sept. 12, 2025. (Malinda Hartong for The Epoch Times)

Applause and Concerns

The technology’s role in law enforcement has become increasingly important, Beal said.

He believes that we are approaching the point at which “it’s almost negligent” if departments fail to use every tool available, including drones.

That is particularly true in “search-for-persons operations” and high-risk incidents, Beal said. Those might include police serving search warrants targeting dangerous people or police responding to shootings-in-progress, unruly crowds, or standoffs with barricaded suspects.

In such circumstances, the high-tech devices give officers “an eye in the sky and time on their side,” Beal said.

About 2,500 police agencies own at least one drone, and 400 police departments run some type of Drone as First Responder (DFR) program, Beal estimated.

Those numbers are low, considering that the United States is home to about 18,000 federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

“We’ve got law enforcement agencies buying drones on a daily basis,” Beal said.

Agencies that lack their own drones often borrow them from neighboring departments.

And, as agencies’ drone use expands, people on both sides of the political aisle are raising concerns, he said.

In Eureka, California, an Oct. 17 social media post from a group calling itself “The Humboldt Area Center for Harm Reduction” called drones “militarized police technology” and “fascist.”

“Research is only the first step,” the post reads, alleging that police would move toward “a military drone surveillance program.”

Beal said it is impractical—and irresponsible—for agencies to deploy drones for general surveillance. It makes no sense for officials to say, “We’re gonna go out and fly a drone for 10 hours today and hopefully find something,” he said.

Misusing the technology, he said, could ignite backlash against drone programs across the United States.

Beal’s 2,000-member nonprofit helps train drone operators and sets standards to ensure that the technology is being used “the right way,” he said. His group assists public safety agencies not only across the United States, but also in Canada, Europe, South America, and Australia.

A drone operator flies a Chula Vista Police Department drone in Chula Vista, Calif., on Aug. 21, 2025. Authorities said the drone provides precise location data that guides officers and enables a rapid response. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Tales From 2 Cities

To learn more about police drones, The Epoch Times visited the Chula Vista Police Department and the Cincinnati Police Department, which began its drone program over the summer.

Although the two departments are located 2,200 miles apart and serve starkly dissimilar communities, they follow some of the same key principles. Their drone pilots must be federally certified, and their policies prohibit general patrolling or random surveillance with drones.

Unique factors affect police drone operations in each city.

Chula Vista, which means “pretty view” in Spanish, enjoys Southern California weather that is reliably clear and sunny: ideal drone-flying conditions.

And it is a low-rise city, with buildings mostly 20 stories or lower, simplifying drones’ flight paths.

The police headquarters building is only about four stories high, but its rooftop enables a miles-wide view. It is one of the locations from which police launch drones.

Under federal rules, a person must be present at the site; that is typically a contractor who performs maintenance on the drones and coordinates flights with a drone operator inside the building. The indoor employees operate controls and monitor computer displays of maps and drone-collected images.

In contrast, Cincinnati faces more obstacles for its drone flights.

Midwest weather tends to be more fickle, and skyscrapers form the Queen City’s distinctive skyline, posing challenges for drones. Tall buildings can disrupt GPS signals that guide the aircraft. The structures also may create a “canyon wind effect” that can destabilize drones.

Numerous federal flight restrictions affect Cincinnati airspace, too. While Chula Vista lacks a professional sports team, Cincinnati is home to three: Reds baseball, Bengals football, and FC Cincinnati soccer. Those teams’ schedules and the presence or movement of Vice President JD Vance, whose permanent residence is in Cincinnati, all can cause the FAA to impose restrictions.

Spc. Matthew Martin pilots a drone at the Cincinnati Police Department in Cincinnati on Sept. 12, 2025. (Malinda Hartong for The Epoch Times)

Cincinnati encompasses nearly 80 square miles of hilly land and water. That is about 30 square miles larger than Chula Vista, a mostly flat Pacific coastal plain just north of the U.S.–Mexico border.

Furthermore, because Cincinnati was incorporated nearly 100 years before Chula Vista, much of Cincinnati’s land is more densely packed with structures. That characteristic could also affect drones’ maneuverability and sight lines.

So while Chula Vista police enjoy more favorable drone conditions, Cincinnati police say they have figured out how to overcome hurdles in their local landscape.

Tragedy Sparked Innovation

The idea for Chula Vista’s drone program dates back a decade or so.

English recalled that about a decade ago, then-Capt. Roxana Kennedy was lamenting a tragedy in a neighboring community.

A man having a mental health crisis had positioned himself in a ready-to-shoot stance. To defend themselves, officers opened fire, killing him. They later learned that he was holding a harmless shiny object, not a gun.

Kennedy and other officers brainstormed how to prevent such a terrible outcome in the future. They designated a small team of plainclothes officers to go to critical incidents in unmarked cars. That advance team used binoculars and radios to “start providing real-time intelligence” to arriving officers, English said.

According to English, after that approach proved effective, then-Lt. Fritz Reber wondered, “What if we did the same thing with drones?”

After Kennedy became chief in 2016, Chula Vista held community forums to address questions and concerns. Community opposition had killed proposed drone programs in other cities.

A committee worked with the FAA to learn rules governing drone flights. The department earned federal approval to fly drones for tactical purposes in 2017, paving the way for the drone program the next year. In 2021, the FAA granted citywide approval for drone flights.

“It’s hard to be the first, because there’s a very bright light that shines on you,” English said. “[Kennedy] had the guts to make the leap.”

Capt. John English stands in a hallway at the Chula Vista Police Department in Chula Vista, Calif., on Aug. 21, 2025. English said drones provide real-time intelligence to responding officers, improving decision-making and helping prevent an overreaction to a perceived threat. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Evaluating Effectiveness

Since the program’s inception, Chula Vista drones have flown nearly 25,000 missions and assisted in about 3,800 arrests. For the highest-priority calls, drone on-scene arrivals averaged 3.7 minutes, compared with six minutes for patrol cars, according to figures on the department’s Drone-Related Activity Dashboard on Oct. 28.

Police in Chula Vista are deploying drones with increasing frequency. In 2019, the first full year of the program’s operation, drones flew to about 1 percent of calls for service; by 2023, that number grew to nearly 5 percent, according to Government Technology magazine’s 2024 analysis.

Sgt. Manny Salazar, drone unit supervisor, told The Epoch Times that first-response drones, which run about $35,000 each, are far less expensive aerial aids than helicopters, which he estimated at $1 million apiece.

However, he said, it is hard to quantify program cost savings, such as the vehicle gasoline preserved in 4,500 instances in which a drone arrived and showed that there was no need for an officer.

“The financial benefit of saving a life, reduced use of force, reduced injury or hospitalizations of officers, faster response times, and better intelligence gathering [are all difficult to tally],” a 2024 Justice Department case study of Chula Vista’s drone program states.

“The impacts of the drone program are demonstrated through narratives of drone use and supported by video gathered by the drones themselves.”

Chula Vista’s police department employs fewer than 300 officers and is considered understaffed for a city of its size, English said. Police often say drones act as a “force multiplier,” meaning that drones maximize what each officer can accomplish.

Sgt. Manny Salazar, supervisor of the drone unit, prepares a drone for flight at the Chula Vista Police Department in Chula Vista, Calif., on Aug. 21, 2025. Salazar said first-response drones cost about $35,000 each—far less than helicopters, which he estimated at $1 million apiece. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Tactical and Mapping

In Chula Vista, police use drones in three different ways.

For the first-response drone program, devices sit in “nesting states,” awaiting activation, at four main launch sites, including police headquarters. The DFR unit is staffed during specified periods, including peak 911 call times. An experienced sworn officer known as a “teleoperator” decides when a drone should be deployed.

Another type of drone use involves specially trained officers who can sign up to take one of 20 smaller, “tactical” drones with them for use during their shifts. Those drones take several minutes to set up, so they are typically used for less urgent situations such as surveying the building an officer is about to enter during a requested “wellness check” of a person with potential mental health issues.

With both first-response and tactical drones, the drone pilot can connect the device to a system that allows responding officers and commanders to watch drone-fed images of events on their cellphones in real time.

A third type of drone use—mapping traffic and accident scenes—has cut accident investigation time “at least in half,” a case study shows.

The department strives to be transparent, Salazar said, and its website displays maps of all drone flight paths.

Willingness to answer questions and provide information has allayed most concerns and converted many skeptics into supporters, Salazar said.

Despite community outreach, only 34 percent of people surveyed were aware of the drone program, according to a 2024 Criminal Justice Clearinghouse report. However, when those people were told about the program’s functions, more than nine out of 10 respondents were supportive, the report states.

Meanwhile, Chula Vista’s DFR program has faced a notable court challenge: a four-year legal battle over a journalist’s request for a full month of drone video footage.

Courts have ruled that police cannot withhold all such videos as “investigation records.” Yet at the same time, California’s strict privacy laws compelled police to review the footage case by case.

On Oct. 22, the newspaper that filed the lawsuit, La Prensa San Diego, reported that a judge had ordered Chula Vista to pay $500,000 in legal fees and other costs. The newspaper also reported that the case is considered precedent-setting and could affect other police agencies that use drones.

Chula Vista’s legal department did not respond to a request for comment.

A computer screen displays an image from a drone's camera, monitored by a member of the Cincinnati Police Department's drone unit, on Sept. 12, 2025. (Malinda Hartong for The Epoch Times)

Stepping Up to the Launchpad

Police in Cincinnati confront higher crime rates than their peers in Chula Vista.

In 2024, the Queen City’s violent crime rate was 7.28 per 1,000 citizens, according to NeighborhoodScout’s analysis of FBI data. Chula Vista’s rate was about half that level, at 3.60.

Crime became a major political issue in Cincinnati this year. Local outrage gained national attention after a racially divided, videotaped brawl went viral online.

Earlier this year, Cincinnati Police Chief Teresa Theetge announced multiple steps the city was taking to address crime, including launching drones.

A month before the drone program’s official rollout in July, police used a drone’s spotlight to disperse an unruly nighttime crowd downtown.

But the drone program is not a product of the recent crisis.

In fact, it was “years in the making,” Police Lt. Jonathan Cunningham told The Epoch Times. He said police leaders, including Theetge, became increasingly interested in the technology after hearing success stories from other departments. The process began four or five years ago.

Cincinnati police followed Chula Vista’s example and met with community leaders before rolling out its DFR program; officers met with heads of all 52 community councils to seek input and familiarize them with the department’s planned use of the technology, Cunningham said.

In addition, Cincinnati’s main DFR-use policy resembles Chula Vista’s.

“Drones will be used only in response to dispatched calls for service—not for random surveillance or general patrol—and their cameras remain pointed at the horizon during flight to protect privacy,” a city of Cincinnati statement reads.

“This program represents a major step forward in the department’s commitment to using innovation to keep Cincinnati safe.”

The department started the program with nine drones capable of covering about 40 percent of the city; the department is aiming for 90 percent coverage within a few months.

Police Lt. Jonathan Cunningham discusses how the Cincinnati Police Department operates its new “Drone as First Responder” program in Cincinnati on Sept. 12, 2025. (Malinda Hartong for The Epoch Times)

Cincinnati’s Distinctive Features

Cincinnati’s DFR program differs from Chula Vista’s in a few notable ways.

While Chula Vista’s drones are labeled “Chula Vista Police,” Cincinnati’s drones fly with blue-and-red lights, a more visible indicator that the drone represents law enforcement.

Also, while Chula Vista puts a person on the roof at the launch site to observe the skies and clear the airspace—as the FAA requires—Cincinnati obtained FAA approval to use a radar-and-camera system, DedroneBeyond.

Sgt. Jay Kemme, supervisor of Cincinnati’s drone unit, explained that the system fulfills the FAA’s requirement for a “visual observer.”

“It tells us where the planes are, how high they are, the helicopters,” he told The Epoch Times. “And if there’s something in our area, it'll beep, so we know we have to get out of the way of that.”

Cincinnati also figured out how to help minimize the effects of sometimes-unfriendly southwest Ohio weather. The department houses its drones in a climate-controlled charging dock.

“It’ll stay warm in the winter and cool in the summer. ... It’s all-weather,” said Officer Ben Miller, a remote drone pilot.

Miller said he marvels at the devices’ capabilities and “how incredible it is that [police] can get to virtually anywhere” while the drone’s battery lasts. If a battery gets low, police can send a backup drone and command the original to return to home base for recharging, he said. Using this “leapfrog” method, drones can monitor scenes for prolonged periods if necessary.

Drones are sent after reports of “everything from a shooting to a mattress on the highway,” Kemme said.

By the end of October, Cincinnati’s drone unit had already surpassed 3,000 flights, he said. That is more than triple the number of drone responses listed on Chula Vista’s dashboard since July, when Cincinnati’s program started.

“I would like citizens to know that it’s keeping them safer,” Kemme said. “[When citizens call 911] we’re going to get there really fast ... and if we see that it’s a serious situation, now we can rush resources to you faster.”