At certain moments, history coalesces into a single decisive moment when the future depends on the actions of a few courageous people. Not infrequently, the contour of world events has been shaped by the military action occurring on one, pivotal battlefield. A last stand, a desperate charge, a bold tactic—and a new chapter of history begins. This article outlines five of these world-shaking battles that made and unmade empires and rewrote our collective story.

Salamis

The Battle of Salamis, 19th-century illustration. (Public Domain)

In late September, 480 B.C., the Greek world—and with it, the germ of Western civilization—stood on a knife’s edge. A decades-long revenge story had reached its climax. In the final years of his reign, the Persian emperor Darius seethed with anger at the Athenians because they had assisted their fellow Ionian Greeks in a revolt against Persian rule.

Darius was determined to punish the Athenians, but due to his army’s defeat at Marathon in 490 B.C., he didn’t live to see the proud Athenian helm crushed beneath Persian feet. So Darius’s son Xerxes shouldered his father’s mission and sent a large navy and army against the Greeks 10 years after Marathon.

This led to a string of battles etched forever in the gilded annals of history: Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea. The story of Thermopylae has been told elsewhere. Though it’s remarkable for the Spartans’ heroism during the battle, it wasn’t the most decisive of this triad. That honor goes to the naval battle of Salamis. As “Great Battles: Decisive Conflicts That Have Shaped History,” edited by Christer Jorgensen, put it: “At Salamis, the Greeks inflicted a crushing naval defeat on the invaders and preserved the flower of Western culture.”

The Spartans’ delay at Thermopylae bought time for the rest of the Greek forces, and as a result of this delay, 200 Persian ships were caught and destroyed in a storm off the coast of Euboea. But after the brief halt at Thermopylae, the Persian juggernaut rolled on. Greek city-state after Greek city-state surrendered to the overwhelming invading force. But Athens and Sparta refused to capitulate. The Spartans dug in on land. Meanwhile, the Athenians retreated from their own capital and withdrew their navy to the narrower, more protected waters between Athens and the island of Salamis.

Persian ships were built for maneuvering on the open ocean and didn’t handle well in the shallower, island-studded waters near Salamis. Although the Persian fleet outnumbered the Greeks by at least 100 vessels, their formation was broken in the narrow waters and their pursuit of a feigned Greek retreat left them exposed. They were then shattered by sudden ramming by the orderly Athenian ships. The Persians lost half their fleet. The Greeks lost only 40 ships of between 300 and 400.

Though some Persian forces remained to be contended with—notably at the Battle of Plataea, which the Greeks also won—the Persian expedition was crippled from this point on. The “wooden wall” of the Athenian navy had saved Greek civilization.

In “100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present,” Paul Davis wrote: “The Persian naval defeat, followed by the military defeat at Plataea, ended the attempt to expand the Persian Empire into Europe and made the Greeks the dominant population in the Mediterranean region and Europe.”

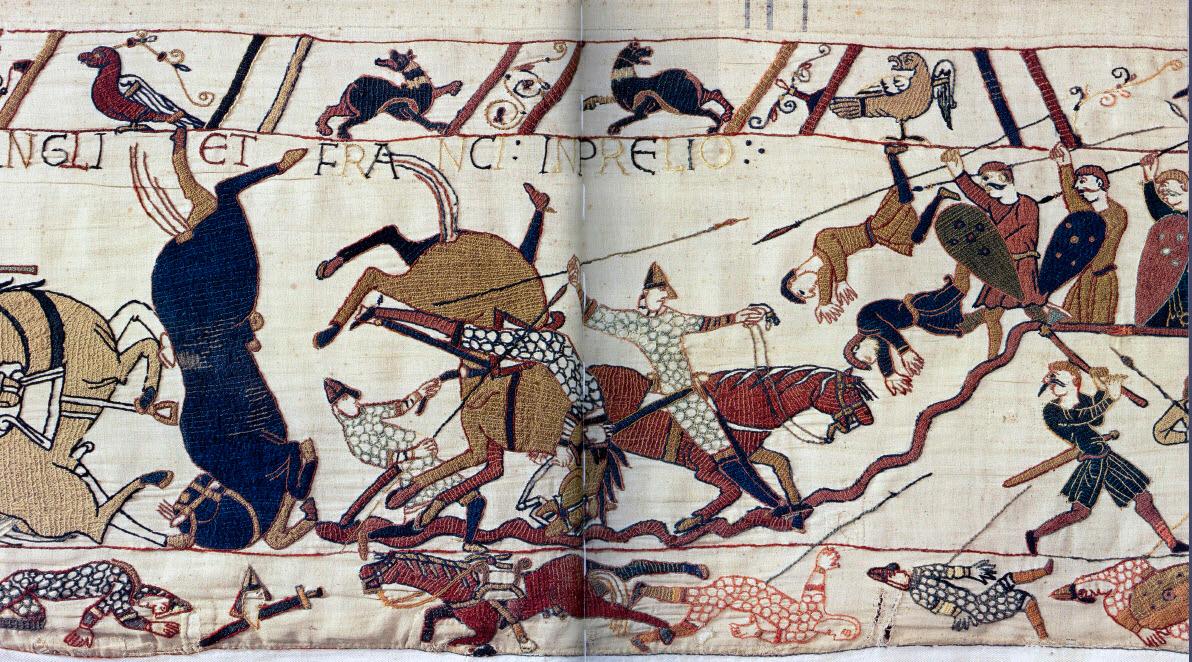

Hastings

Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings. (Public Domain)

When Edward the Confessor died childless in January of 1066, two men laid claim to the English throne he left vacant: Harold Godwinson and Duke William of Normandy. The Anglo-Saxon nobles threw their support behind Harold, and even Edward himself had apparently named him successor before he died. Across the English Channel, however, William strongly contested the claim. Back in 1064, William had forced Harold to swear an oath that he would leave the throne for William. Now, the English nobles didn’t care, and Harold himself hardly felt bound by an oath sworn under the pressure of threats and blackmail.

Harold was crowned king in Westminster Abbey the same month that Edward died, but he knew that the viciously ambitious William wouldn’t let the matter rest. Both sides began mobilizing forces for the inevitable Norman invasion of England. At the same time that Harold had to deal with the rising threat of William, another, unexpected gale broke on British shores: a Viking invasion. Harold rushed his troops north and defeated King Harald Hardrada of Norway at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Almost immediately, he had to march back south to face the newly landed Norman force.

The Battle of Hastings occurred on Oct. 14, 1066. Harold’s warriors formed a solid shield-wall atop Senlac Hill, and William’s troops gathered at the foot of the embankment. One of William’s strengths was his cavalry—particularly due to the invention of stirrups, which helped keep a knight steady as he wielded a lance. But the Anglo-Saxon shield-wall atop a steep hill stood almost impervious to a cavalry charge. William’s plan, then, was to get Harold’s warriors into more open, even terrain where his cavalry could dominate.

A few initial assaults against the well-ensconced Anglo-Saxons proved fruitless, and rumors of William’s death made the Normans falter. But William appeared before them without his helmet to prove he was still alive, and this rallied the men. Then, William ordered them to fake a panicked retreat. As he predicted, a good portion of the Anglo-Saxon line broke and pursued the “retreating” Normans.

William sprung his trap: Now that Harold’s men were in the open, dislodged from their hill, his cavalry could eviscerate them. Harold and his best men remained atop the hill, but the Normans peppered them with arrows, one of which struck Harold in the eye and killed him. This broke what morale the English still possessed, and the day was William’s.

The influx of Norman rulership into Anglo-Saxon England profoundly reshaped the country’s contours of European power dynamics. William introduced a centralized form of feudalism, Norman culture, and French language. He restructured the nation’s laws, politics, and culture, creating a stronger, more centralized monarchy. “Before the invasion, England had been a loose confederation of nobles more than a country; afterwards it became a real nation,” wrote Michael Forbes, a contributing author, in “100 Decisive Battles.”

Lepanto

"Naval Battle of Lepanto (October 7, 1571)," 1887, by Juan Luna. Oil on canvas. Palace of the Senate, Madrid. (Public Domain)

Throughout the Middle Ages, Muslim forces attacked and invaded Christian Europe. Not infrequently, Europe was but a whisper away from being overrun by the caliphs of Africa and the East. Yet, with the exception of Spain for a period of time, Europeans managed to maintain their independence. But in 1571, the Muslim Ottoman Empire of Turkey launched a massive invasion force by sea. It appeared that Europe would at last bow to the ascendant crescent.

After the brutal fall of Famagusta to the Turks in August 1571, the Papal States, Spain, Venice, Genoa, and Malta (among others) formed the Holy League. They combined their navies under Don John of Austria to counter the oncoming Turkish forces. The Holy League’s ships were fitted with innovations that served them well in the battle. As “Great Battles” notes, they relied on cannons more than the traditional methods of ramming or boarding enemy ships. They also made use of fence-like nets that made it more difficult for the enemy to board the ships’ sides.

The two fleets met in the Gulf of Patraikos, near Lepanto, in Greece. Both sides opted for a conventional straight line of battle. The Christian fleet consisted of three divisions with a reserve division behind the main fleet. At first the wind favored the Turks, but then it shifted to favor the Christians. The Turkish ships took heavy damage from the Holy League’s withering cannon and arquebus fire—the latter a heavy, long gun similar to a rifle.

In some areas of the massive battle, ships came alongside one another and each side attempted to board and capture the other. The galleys of Don John and Turkish Grand Admiral Ali Pasha met and the two sides fought upon the ships’ decks. Don John was wounded and Ali Pasha killed; the death of the Grand Admiral broke Turkish morale. The center of the Turkish fleet collapsed.

On the left flank, Christian galley slaves revolted against their Muslim masters, turning the tide of battle in that sector. On the other side, to the south, the Turks had more success, but it wasn’t enough to snatch a victory; overall, the Turkish forces were largely annihilated. History lecturer Christopher Check called Lepanto “the most important naval contest in human history ... the battle that saved the Christian West from defeat at the hands of the Ottoman Turks.”

Incidentally, it may also have provided the Spanish novelist Cervantes, who fought and was injured in the battle, with inspiration for his future works.

Waterloo

"The Battle of Waterloo" by Thomas Jones Barker. This painting depicts the decisive moment that marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars. (Public Domain)

The grueling Napoleonic Wars had stretched on for over a decade by the time Napoleon was finally defeated and exiled to the island of Elba in 1814. The war had pitted various European coalitions on one side against the French government—the First Republic (1803–1804) and French Empire (1804–1815)—on the other. The French were led by Napoleon, who seemed intent on ruling all of Europe and beyond.

But like a repeating nightmare, Napoleon appeared in France once again on March 1, 1815, after the European coalition thought they had finally dealt with him through exile. The coalition couldn’t suffer his return since he'd often disturbed European peace, so they mobilized against him. Though the French were tired of bloodshed, they also mobilized under the man who had led them to heights of glory.

The coalition had two main armies: a British one led by the Duke of Wellington, and a Prussian army under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Together, the forces numbered about 113,000 men. Napoleon led about 72,000 Frenchmen. His best chance of victory was to prevent the two enemy armies from joining forces and to defeat them piecemeal, a technique at which he had many times proven his acumen.

Europe’s long, bloody, blistering attempts to rid itself of the brilliant and unbeatable Napoleon came to a violent climax on June 18, 1815. Napoleon fared well in the battle, at first. He drove the Prussians back at Ligny, although poor intelligence and the failure of subordinating officer Marshal Grouchy prevented Napoleon from taking full advantage of this victory. The Prussians were down but they weren’t out, and Napoleon failed to realize that the well-disciplined Prussians had recovered from the defeat and emerged largely intact. Meanwhile, Napoleon’s sights were on Wellington, who had retreated toward the village of Waterloo and taken up a position on the ridge south of Mont-Saint-Jean.

Napoleon began his assault on Wellington’s position with an artillery bombardment. Then, he attempted a diversionary attack on a side wing of the enemy forces entrenched in a nearby chateau. Napoleon followed this up with his main assault on the coalition left center, driving back the enemy infantry. But once the French crested the ridge, they were counterattacked by British infantry and cavalry, who pursued them until the British, also, were counterattacked by French horsemen.

Neither side gained a clear advantage, and time was running out for Napoleon as the recovered Prussians began to arrive on the battlefield, pressuring Napoleon’s flank. In a final attempt to break the enemy line, Napoleon deployed his elite Imperial Guard troops, who assaulted Wellington’s ridge. But even they were unable to puncture through, and ultimately they broke and ran. This caused panic to sweep the French forces like an ill wind. Even a brilliant general like Napoleon couldn’t salvage the situation.

After his defeat, Napoleon was again exiled, this time to the barren island of St. Helena—from which, this time, he would not return. His empire collapsed, and four decades of peace finally came to Europe. The Napoleonic Era—which had defined European culture and politics for so long—was now over.

D-Day

American troops stand by on Omaha Beach after the D-Day landings in June 1944. (MPI/Getty Images)

The immense importance of the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II can hardly be tabulated. As Davis wrote: “The Normandy invasion marked the point beyond which Hitler’s dream of German-dominated Europe could not be revived.” It marked a major intervention by the Americans in the war and solidified the Allies’ ascendancy. The liberation of Western Europe that followed promised peace, the reversal of the dark future that would have ensued after a Nazi victory in the war.

The D-Day landings also stand out as one of the most successful amphibious assaults in modern history. They required meticulous planning, patient preparation, and webs of deception. The British initially hesitated to attempt an all-out assault on the French coast, preferring to hammer away at the Mediterranean campaign instead. But the Americans’ bolder strategy eventually won out. “Operation Overlord” was born.

It was impossible to completely hide the massive buildup of troops, planes, and ships across the channel from Hitler’s France. The Allies focused instead on deceiving the Germans about where the invasion would come. Using various forms of trickery, including inflatable tanks and other dummy equipment to create apparent force buildups in the wrong place, the Allies convinced the Germans that the attack would come on the Pas-de-Calais coast—with the Normandy assault a mere diversion.

The first troops sent into the fray were American and British airborne forces, sent in darkness in the wee hours of June 6, 1944, to capture key bridges and secure the flanks for the main thrust of the coming attack. Two hours after the initial paratrooper assault, Allied bombers began blasting German defenses in the area of the invasion. At dawn, the naval bombardment commenced. Meanwhile, the Allied fleet launched into the deep with six target beachheads: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

Initial success varied across the different beaches, with the Americans taking Utah with relative ease. Omaha, on the other hand, due to bad weather conditions and insufficient intelligence, turned into a bloodbath where a mere 2,000-yard foothold cost 2,000 casualties. The British–Canadian assault on Juno proved similarly costly, though ultimately the beachhead was secured.

Despite such setbacks, the first day of the assault proved highly successful. The Allies had maintained the element of surprise and landed over 130,000 men at the cost of 10,300 casualties. Within a week, another 200,000 men and tens of thousands of vehicles had landed. However, the Allies, bogged down by stiff German resistance and armored flanking movements, failed to break out from the coastal areas and penetrate inland as quickly as they hoped.

Still, with determined effort, the Allies managed to break through German lines in “Operation Cobra” on July 27. This, along with Hitler’s refusal to permit a strategic retreat, allowed the Allies to encircle the Germans in an operational cauldron (the “Falaise pocket”), killing 10,000 and capturing 50,000 more.

Like the other battles in this list, the dawning of D-Day wasn’t just a new day of the war. It marked a new day in world history. Each of these battles teaches us how the future of the globe sometimes hinges on a single moment of daring and courage.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misnamed the Papal States.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc