In the silence of night’s lost hours, before an altar and an icon, with candlelight flickering over cold stones, a man kneels. On the altar lie his weapons; their placement symbolizes that they belong to God and must be used to defend justice, truth, and honor. The squire pours out his heart to God all through the dark night, begging for the strength he will need to fulfill his calling as a knight. When the red stripes of dawn finally cut the sky, the squire knows that the moment of his transition to knighthood isn’t far off.

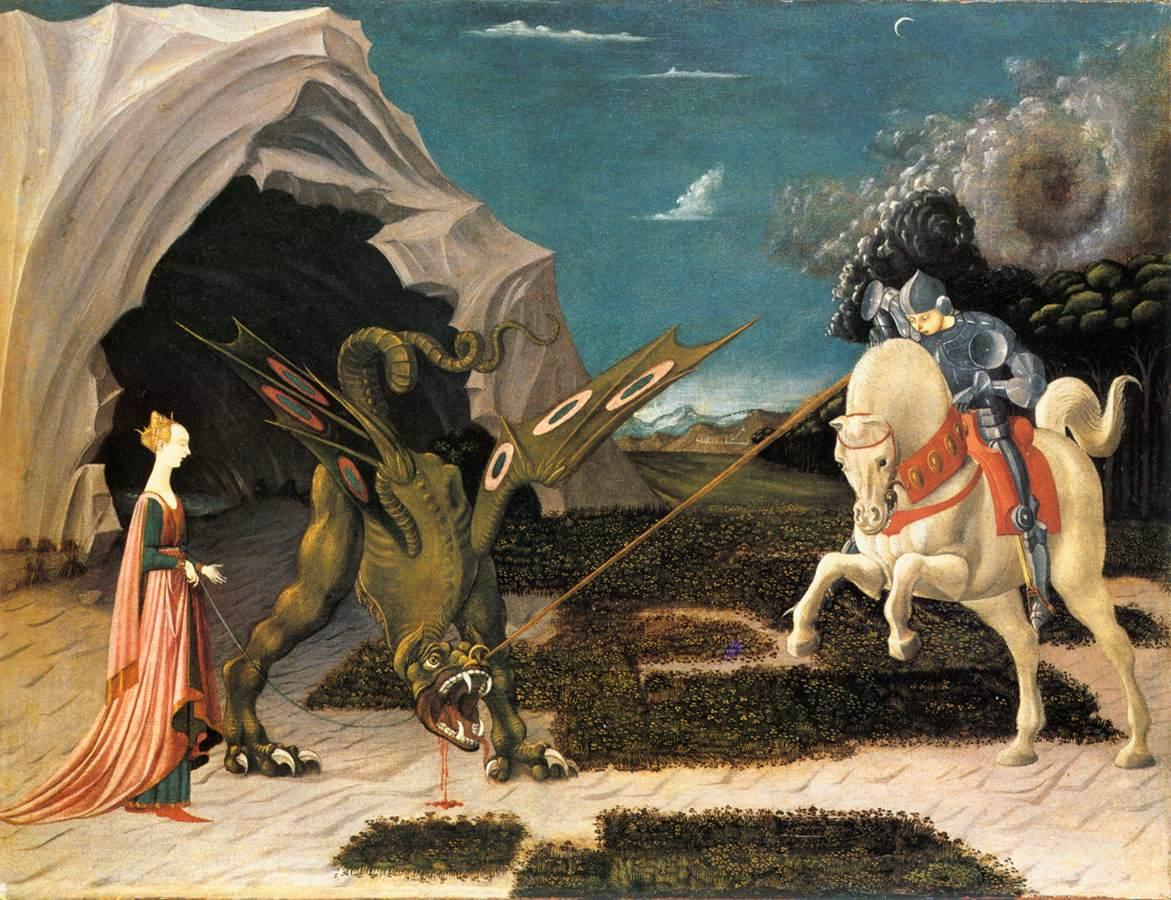

The elaborate ceremonies surrounding the creation of a knight in medieval European society reflected the high ideals involved in the medieval conception of the warrior. Though knights didn’t always live up to those ideals, of course, they tell us something about the medieval worldview and the role of the gentleman and warrior within it.

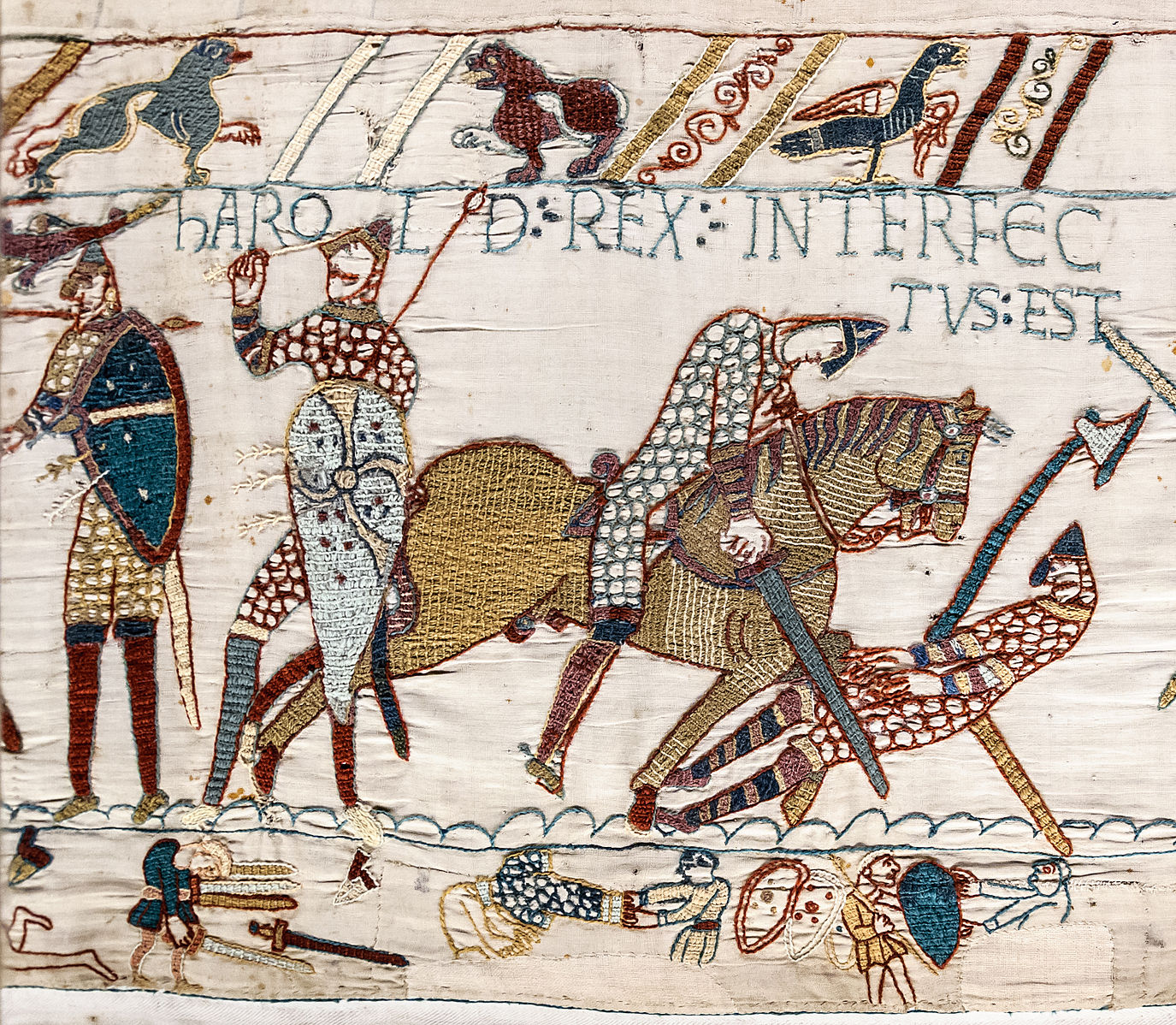

"Saint George and the Dragon," circa 1456, by Paolo Uccello. National Gallery, London. Knights' lives had a spiritual dimension, as evidenced by the story of Saint George and the Dragon. (Public Domain)

The Warrior in Christian Culture

The rituals for the dubbing of a knight express the notion of chivalry, the framework that medieval society developed to bring warfare into harmony with concepts of faith and civility. The concept first emerged in France around the 10th century. The Catholic Church sought to rein in the violent tendencies of the Franks, for whom unchecked bloodlust was a way of life.

Etymologically, “chivalry” derives from the French “chevalier,” a term referring to a warrior on horseback (“cheval” means “horse”). The Franks made use of horses extensively in battle. Generally, only the wealthy could afford to own a horse and ride it into battle, and so knighthood became associated with aristocrats.

To this martial elite, Christianity offered a code of noble ideals in order to direct their violent nature toward the defense of Christendom rather than its destruction. At its best, chivalry was a path to holiness for men whose nature and calling was martial. A truly Christian knight was expected to pursue virtue as vigorously as a monk did.

Like a monk, he was provided with a rule of life to do so: the Order or Code of Chivalry. Knights were expected to defend the rights of God and the Church, help and defend the weak, challenge evildoers, and live in loyalty to their lord or king.

Though tensions always remained between the battlefield’s bloody work and the Christian’s moral code—not to mention knights’ failures to respect the code of conduct they professed—the chivalric ideal, at its best, impressed on its followers that even warfare could be conducted with virtue and honor and at the service of God and man. During peacetime, too, knights played important roles as they distributed justice, managed their estates, and served their liege lords.

In this illustration from an 1870 book on life in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, this Renaissance-era knight wears a full suit of armor; his horse is also decorated in ornate fashion. (Public Domain)

This religious and ritualistic conception of knighthood helps explain why the dubbing of a knight was treated almost like a Church sacrament. In fact, squires preparing for knighthood took a bath and donned white clothes to symbolize the cleansing of sin and the purity of heart with which the young man approached his calling. This ritual was highly reminiscent of baptism.

One of the more detailed explanations of the elaborate ceremonies surrounding knighting comes from the 13th-century knight Ramon Llull. Llull noted that dubbing typically occurred on great Christian feast days. This reinforced the knight’s connection to the Church and supported him with the outpouring of prayers and celebrations associated with an important day in the liturgical calendar.

“The honour of the feast will cause many men to gather that day in that place … and they will all pray to God for the squire,” Llull wrote. A squire spent the night before his dubbing in a chapel, where he prayed and kept watch over his arms: the famous “knight’s vigil.”

This aspect of the ritual pointed again to the knight’s sacred dedication to God. It also demonstrated his ability to endure hardship and loneliness. If a knight was to defend the realm and the Church, it made sense that his final preparation consisted of keeping watch while others slept.

Llull emphasized the importance of the squire beginning his knighthood in a pure, high-minded way: “If [a squire] listens to jongleurs who sing and speak of whoring and sin, from the very first moment that he joins the Order of Chivalry he will have begun dishonouring and scorning the Order.”

After the all-knight vigil, the knight-to-be attended Mass. According to Llull, that the dubbing ceremony was embedded within the Mass highlighted knighthood’s sacred character. The knight approached the altar and swore his oaths to the Order of Chivalry, that is, to honor his commitment to uphold the knight’s code of conduct.

This pledge was followed by a lengthy sermon impressing on the knight the essentials of the Christian faith as well as their relation to the knight’s vocation. Finally, a priest or nobleman invested the squire with knighthood: The squire knelt again at the altar and lifted his eyes and heart in prayer to God. While the squire was engaged in this prayer, the noble or priest girded him with his sword and then struck him a blow on the side of the cheek with the flat of a blade. This was the “dubbing”; it was the only hit a knight had to take without retaliating. It served as a reminder of the suffering the knight must be prepared to embrace for God and king.

These ceremonies beautifully expressed the deeply hierarchical and religious medieval conception of the cosmos. Every person had a specific role to fulfill and a specific place within the larger order of society, which mirrored the order of the entire created universe. For the knight, that place was to train relentlessly for war so that whatever was good, whatever was holy, and whatever was beautiful in his civilization might be defended against those who would tear it down.

"God Speed!" 1900, by Edmund Leighton. Though the Medieval era had long since passed when this painting was created, the stories of courtly love and nobility had a lasting impact on European culture. (Public Domain)

In reality, many failed to adhere to chivalric expectations, pursuing their own profit and using their sword to get it. But others followed the chivalric road. What they aspired to—for all their shortcomings—remains a remarkable and unique monument among the military philosophies of history.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc