Math is hard. Uncovering the foundations of mathematics—the basis of what makes the whole structure work—is harder. A century ago, three men attempted just that. They believed unless they could correct flaws in mathematics’ structure, the edifice that was mathematics might crumble. In other words, mathematics, what Carl Friedrich Gauss called “the queen of sciences,” would become meaningless.

The result was known as the Great Math War, or the Foundational Crisis. A decade-long struggle during the 1920s, it’s the focus of this book. “The Great Math War” looks at the three schools of thought attempting to define mathematics’ foundations.

Logicism tried to solve the paradoxes in mathematics foundations using logic. Formalism treated mathematics as a game with an elaborate set of rules agreed-upon by everyone. Intuitionism claimed mathematics was a flowchart construction of the human mind. Mathematics was baked into the human brain, and not just an abstraction.

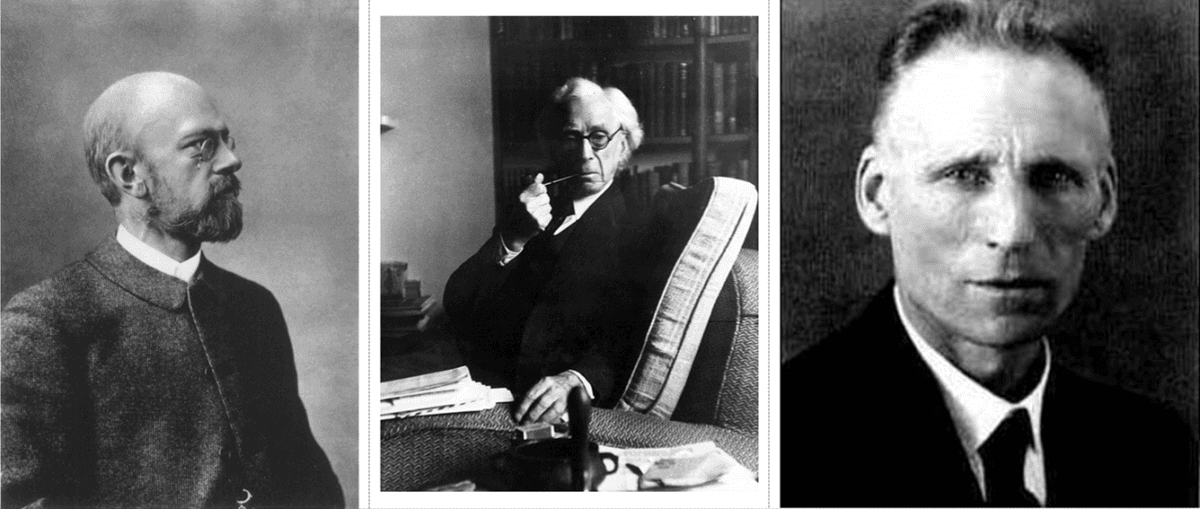

(L–R) David Hilbert in 1907, Bertrand Russell in 1954, and L.E.J. Brouwer, undated. (Public Domain)

A Wild Ride

If this sounds as dry as, well, mathematics, be prepared for a big surprise. Bardi takes readers on a ride as wild as a thriller novel in this history of the math war. Even those uninterested in math will be fascinated by this book.

He begins by introducing one of the book’s three main characters, German David Hilbert, who led the formalist camp. Hilbert gave a mathematics lecture at the 1900 Paris Exposition which reinvented the professional lecture. He was famous for his book “The Foundations of Geometry.” Yet he didn’t speak of that book.

Instead, unexpectedly, his lecture outlines 23 mathematical problems to be solved. It threw down a gauntlet that occupied mathematicians for the rest of the 20th century.

Among the lecture’s attendees, unmentioned by Bardi in this opening, was Bertrand Russell, then a largely unknown 20-something British upper-class gentleman. As shown later, it inspired Russell to become deeply involved in mathematics. Bardi shows how Russell almost casually discovered what is known today as Russell’s Paradox.

Russell’s Paradox upsets one of the then-existing foundations of mathematics, an 1893 book, “Basic Laws of Arithmetic” (“Grudgezetze der Arithmetik”), just as the book was being prepared for a second volume.

The paradox relates to set theory, then a hot topic in mathematics. It forced a major rewrite of the book and led Russell still deeper into mathematics. Along with Alfred Law Whitehead, Russell wrote and released the three-volume “Principia Mathematica” between 1910 and 1913. It became the basis for logicism—the attempt to reduce mathematics to symbolic logic. It also marked, as Bardi shows, Russell’s departure from mathematics to focus on antiwar activities.

The third champion was Dutch mathematician L. E. J. Brouwer. Largely forgotten today, he was known prior to World War I for his work on topology. In the early 1920s he challenged Hilbert’s approach to foundational mathematics dubbing it “formalism.”

Brouwer mathematics was the result of human mental activity, not the discovery of fundamental principles existing in objective reality. He called this approach intuitionism, as the validation of mathematical principles relied on human intuition.

All three approaches seem obscure, highly abstract, and often baffling. Yet as Bardi presents the story, it takes on exciting life, engaging the readers in an adventure through the world of academic Europe in the 1890s through the 1930s.

This is more than a study of numbers.

Distinct Personalities

Bardi presents the background to the Math War. He introduces the important mathematicians of the period leading up to and through the foundational crisis. They aren’t presented as dry mathematicians, but as fully-formed people with individual motivations, strengths, shortcomings and prejudices.

He shows how they reacted to each other, their fights, rivalries and allegiances. Some (including Russell and Brouwer) are revealed as great intellects but appalling individuals.

The real world intruded on the academic world, most notably the effects of WWI and the Nazi rise in Germany. Bardi shows how the University of Göttingen was the axis of the mathematical world in the 1800s through early 1900s.

A virtual Who’s Who of the mathematical world passed through this small university town during that period. Hilbert, Heisenberg, and Max Born taught there. WWI left it isolated and ostracized, while the Nazi purge of “Jewish science” resulted in its intellectual disintegration.

Bardi also shows the outcome of the math war. Brouward’s views were swept from the field, leaving Hilbert the apparent victor. Then, Kurt Gödel’s 1931 incompleteness theorems knocked the underpinnings out from logicism, formalism, and intuitionism.

Triumph turned to ashes; the ashes were scattered two years later by the Nazi intellectual destruction of Göttingen. Mathematicians turned away from trying to perfect its foundations.

“The Great Math War” is a book worth reading, even if—perhaps especially if—mathematics holds no great interest for you.

Bardi’s account is lively and engaging, humanizing mathematics and those who practice it. He presents the world of mathematics that’s very approachable to every reader.

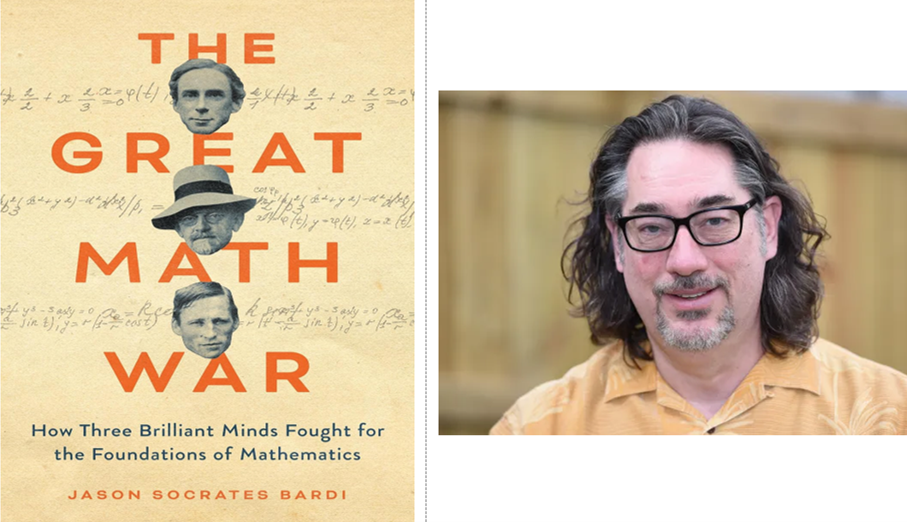

‘The Great Math War: How Three Brilliant Minds Fought for the Foundations of Mathematics’

By Jason Socrates Bardi

Basic Books: Nov. 4, 2025

Hardcover, 416 pages

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc