Australia is considering Mandarin immersion classes in secondary schools, as a federal inquiry examines ways to reverse a steep decline in Asian language study.

The proposal was raised during a hearing of the House Standing Committee on Education, which is exploring whether immersion programmes could lift student engagement and improve proficiency.

This comes amid a fall in Asian language study in schools, despite Australia’s close proximity and strong trade ties with Asia.

The overall uptake of languages has dropped from 11.3 percent of senior students studying a foreign language in 2010 to 7.6 percent in 2023.

Mandarin Chinese, one of the top three languages studied in Australia, plays a big role in public discourse, given China is Australia’s biggest trade partner. The other two languages are Japanese and French.

Mandy Scott, public officer of the Association for Learning Mandarin in Australia (ALMA), noted the prevalence of Mandarin Chinese in the country.

“Mandarin is the second most spoken language in Canberra, and so it should be a good language to learn,” she said at the committee on Dec. 8.

“It is difficult to learn, certainly difficult to write, but there’s lots of opportunity to speak it, because we have such a large population, and I think most cities in Australia are like that.”

Scott also emphasised its high demand.

“Parents are really keen for their kids to get language education, and that’s why I think you can see in most of the private schools, that’s where the very strong language programmes are, because the parents, really, really appreciate the value of it,” she said.

What Are the Benefits?

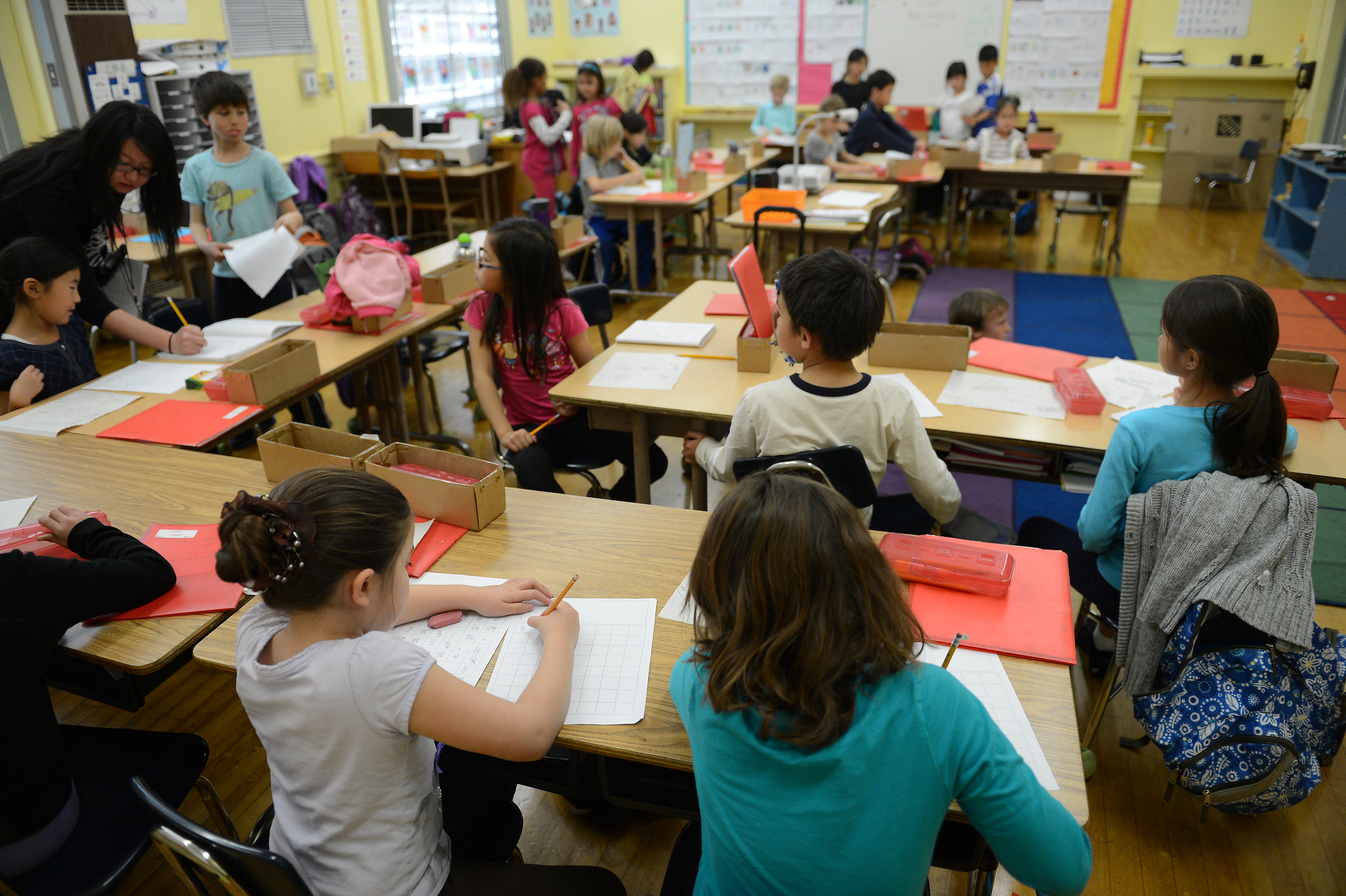

An immersion language programme, a type of educational approach in which students are “immersed” in a language by being surrounded by it in daily activities and lessons, aims to help learners acquire the language naturally, much like how they would learn their first language.

News reports in recent years show the effects of immersion preschools on young Australians.

For Senna Lee, a four-year-old girl, speaking more than one language was made possible due to the immersion program that was offered at a bilingual kindergarten in Chatswood, Sydney.

“When you learn a language, you will know more. Not just your native language, but also, if she is interested in learning about other cultures, it will broaden her perspective in the future,” Senna’s father Mark Lee told SBS in 2024.

The immersion language program offered at the kindergarten teaches both English and Mandarin. For Lee, however, she can speak four languages, including Cantonese and Japanese.

Rachel Qiu, Treasurer of ALMA, who presented with Scott at the committee, shared her insights as a non-native English speaker.

“For myself, English is my second language, and I really see the benefits of learning a second language in an immersion programme,” she told the committee.

Qiu mentioned the programme’s effect in establishing the learners’ cultural identity.

“When I first moved to this country, I noticed, like so many second-generation Chinese kids here, they intentionally abandon their mother tongue,” she said.

“At home, their parents speak Mandarin to them, but they reply to their parents in English, and that’s partly because of the lack of cultural identity confidence.”

Cultural self-confidence refers to one’s belief in their ability to engage with and understand different cultures.

While it is crucial for successful cross-cultural interactions, many foreign language programs nowadays prioritise linguistic proficiency over cultural understanding, according to a 2024 study on building cultural confidence.

“So most of the kids [start] to develop this identity during their teenage age [years], and then it’s very important to continue this study and secure their cultural identity during secondary school,” she added.

What’s Needed?

When asked by Labor MP Tim Watts, who chaired the committee, about what would be required to implement an immersion language programme in high schools, Scott said it would be to get an interested principal first, and then seek out the right teachers.

“They’re having no problem in finding fluent speakers of Mandarin to teach in the primary level,” she said, referring to the situation in Canberra.

“Whether that would be the same at the high school level, I don’t know. But, nevertheless, if they are fluent speakers, proficient speakers, they still have to be competent teachers of whichever stream they were teaching, [such as] social science, or whatever areas of the curriculum we decided to teach.

“So there would be a need for specialist, professional development.”

The ALMA public officer added that giving specialised training to the right teachers could be done nationally.

Scott added that her organisation is “in a good position to have proficient teachers,” given the number of Mandarin teachers.

“But then they have to become proficient teachers of children and professional teachers of children in specific subjects that they require,” she said.