Some 20 years ago, an American history class for homeschoolers was reading Booker T. Washington’s “Up From Slavery.” Rebecca, a bright 12-year-old of my acquaintance, told her parents that she couldn’t really identify with the slavery described by Washington in his autobiography’s first chapter.

On the following Friday evening, with her consent, her parents decided to help her out. They arranged a pallet for sleeping in the corner of the kitchen. Early the next morning, her mother flicked on the overhead lights and commanded her to get up, sweep the floor, and make breakfast. Her parents enjoyed eggs and bacon; Rebecca was given some unbuttered toast. She was assigned chores throughout the day and awarded a light lunch at noon.

Rebecca related this story when we next met. “By suppertime,” she told me with a laugh, “I understood Booker’s life a whole lot better.”

Giving Flesh and Blood to Ghosts

By their unusual approach, Rebecca’s parents invigorated her interest in one of the finest of American autobiographies and in history. Because of the textbooks or the teaching methods, however, many people come away from their high school history classes believing that the past is a bore, a dull and barren desert crossed only to earn a degree.

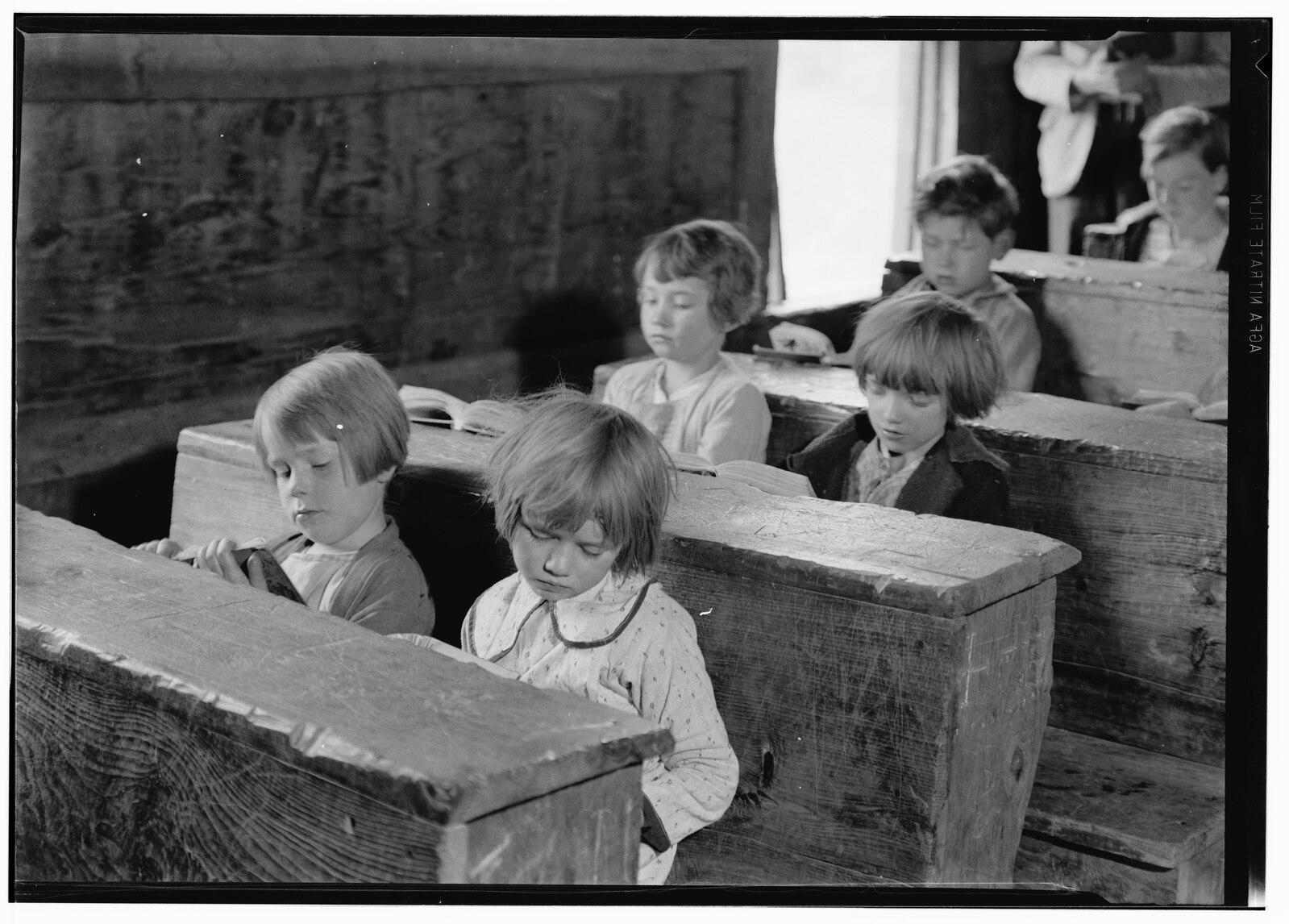

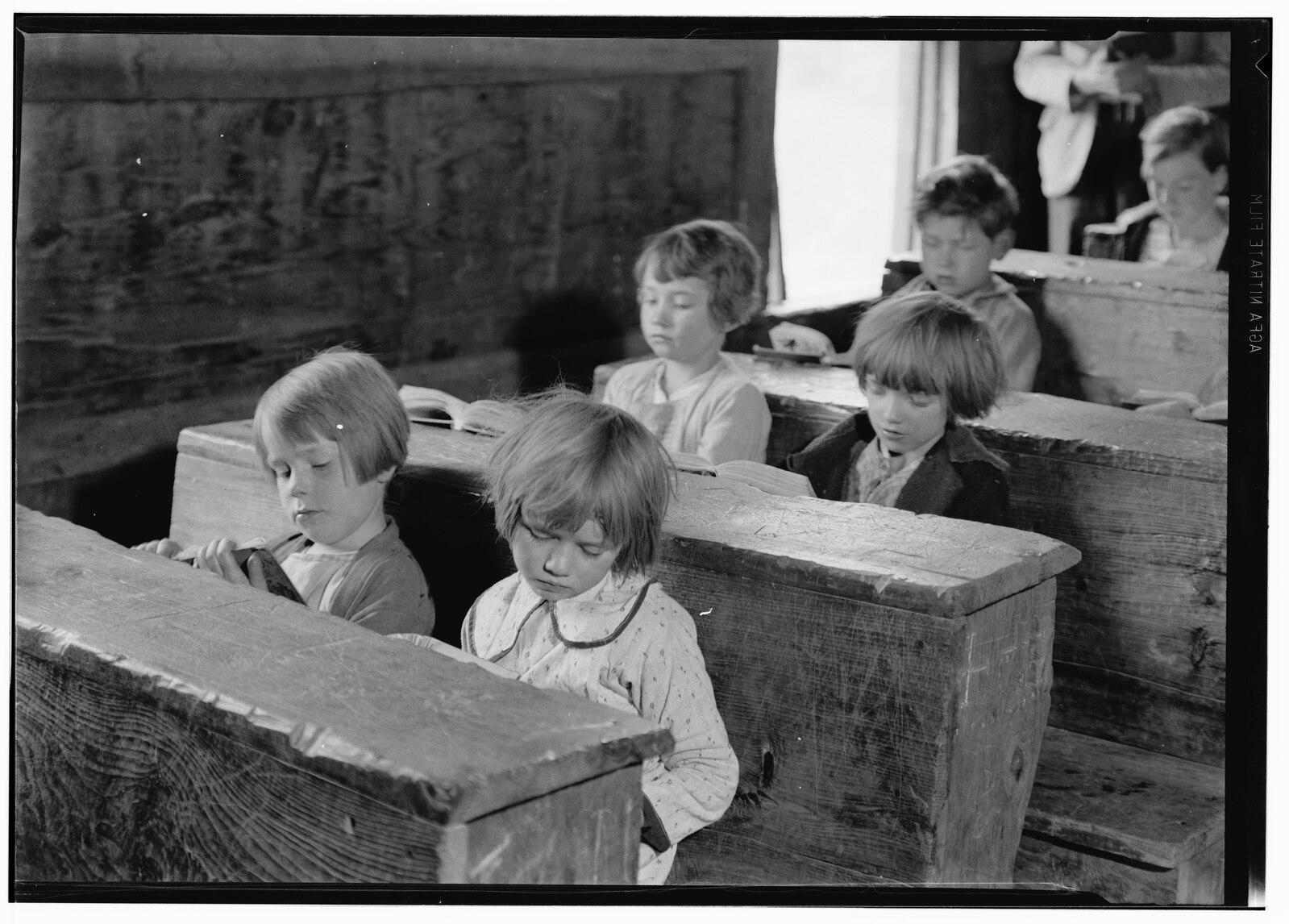

"Detail of the Desks," 1936, by Edouard E. Exine. Library of Congress, Washington. (Public Domain)

Even as adults, these people turn their backs on reading history. No one ever shows them, as Thomas Wolfe put it so eloquently in the beginning of his novel “Look Homeward, Angel,” that “Each of us is all the sums he has not counted: subtract us into nakedness and night again, and you shall see begin in Crete four thousand years ago the love that ended yesterday in Texas.”

The remedy for this antipathy toward history is simple: Find and read those historians who, by dint of knowledge and research, craft in composition, and techniques of imagination, conjure up the ghosts of the past and bring them to life in paper and print. Here are just three of the best of these chroniclers.

The Bostonian

In an

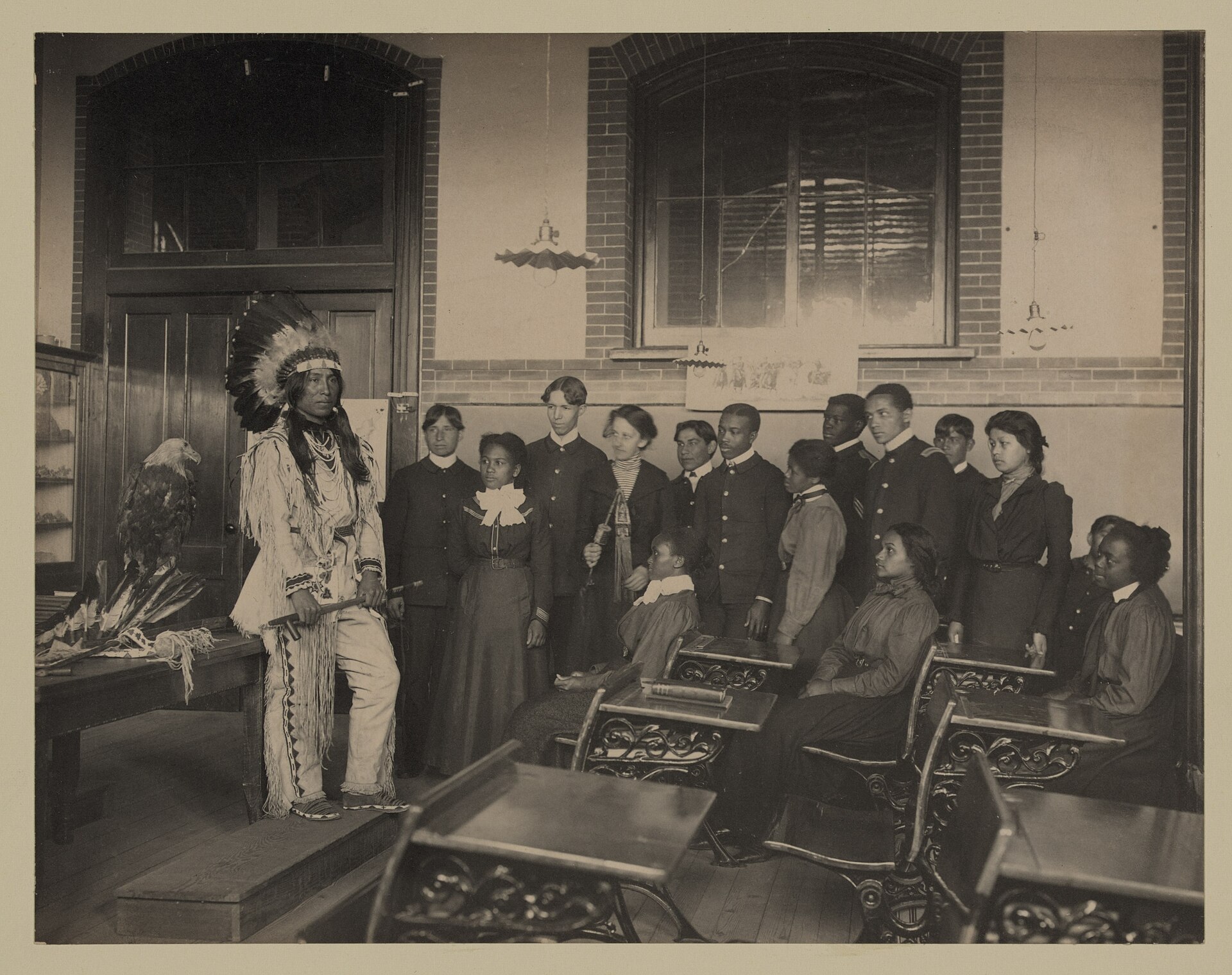

article about historian Francis Parkman (1823–1893) in the October 2014 issue of Harvard Magazine, Castle Freeman writes that Parkman’s father wanted him to “be trained in a respectable profession, having observed that the young man showed signs of eccentricity.” Among those eccentricities was his fascination with nature and with American Indians, the sparks to a lifelong fascination with pre-Revolutionary America.

This interest deepened when Parkman spent two of his Harvard summers in the forests and fields of Maine and New Hampshire, living out of doors, camping, fishing, and hunting, and becoming acquainted with the area’s inhabitants, including Native Americans.

In 1846, still pursuing his passion, he and a cousin traveled west across the Plains, a journey that covered 2,000 miles and took six months. For three weeks of that trek, they lived with the Oglala Sioux, marveling at their physical prowess and studying their customs. This trip was the capstone on Parkman’s ambitious plan to write a history of the struggle between France and England for control of the New World, a contest that ended in the French and Indian War.

Oglala Sioux moccasins on exhibit in the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto. (Public Domain)

Unfortunately, already subject to ill health and eye problems, Parkman became an invalid on his return to Boston, confined to long stints in bed at home. He suffered from depression, and his eyesight often made writing impossible. Determined to write his history, however, and with the help of his family, he forged ahead, relying at times on copyists and secretaries to gather his material, read to him, and take down his words.

His first book, “The Oregon Trail,” was published in 1849 as a blend of history, anthropology, and personal anecdotes based on his travels. A bestseller in the 19th century and now a classic, this book established the young Parkman as writer of note. He then undertook the project that would last his lifetime, researching and writing books about America before the Revolution, including the seven-volume “France and England in North America.” As his health improved, he was able to travel to Europe to further his research.

Though some of Parkman’s conclusions are dated today, and his prose style grander and stiffer than our own, his books continue to attract readers. He had the wonderful, and at that time, rare gift of sifting fact, documents, and personal observations through the sieve of his imagination to create lifelike trappers, Jesuits, military leaders, tribal chieftains, and more.

Francis Parkman (1823–1893), pictured here in 1889, was a controversial 19th-century historian of the American West. (Public Domain)

In describing his approach to history, which differed from most at the time, Parkman wrote:

“The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them. He must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.”

The Virginian

The son of a Confederate veteran who had served with Robert E. Lee,

Douglas Southall Freeman (1886–1953) was a boy when the family moved from Lynchburg to Richmond. There he attended a school where the teacher commonly used Lee as an example in his lessons on virtue. While a student at the University of Richmond, Freeman witnessed a reenactment of the Battle of the Crater performed by men who had fought there. That event so impressed the young man that he was determined to write about them and the cause and state they had defended.

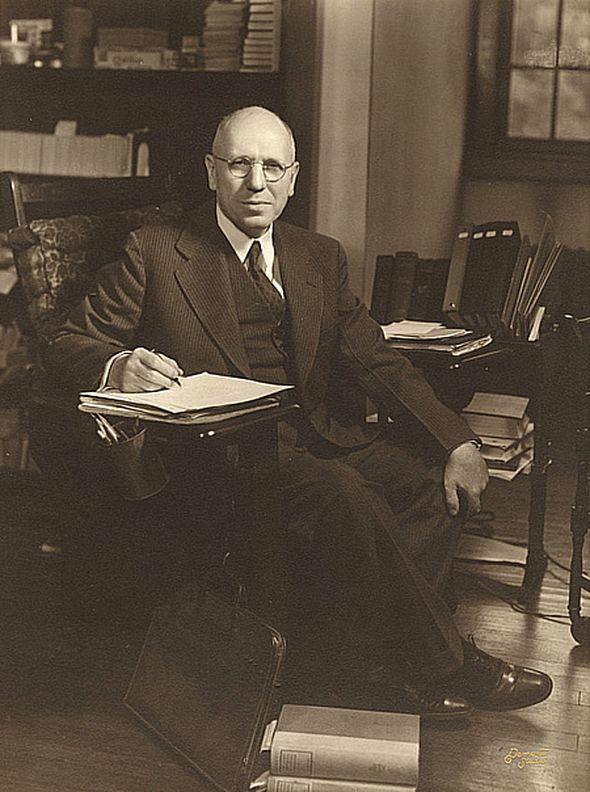

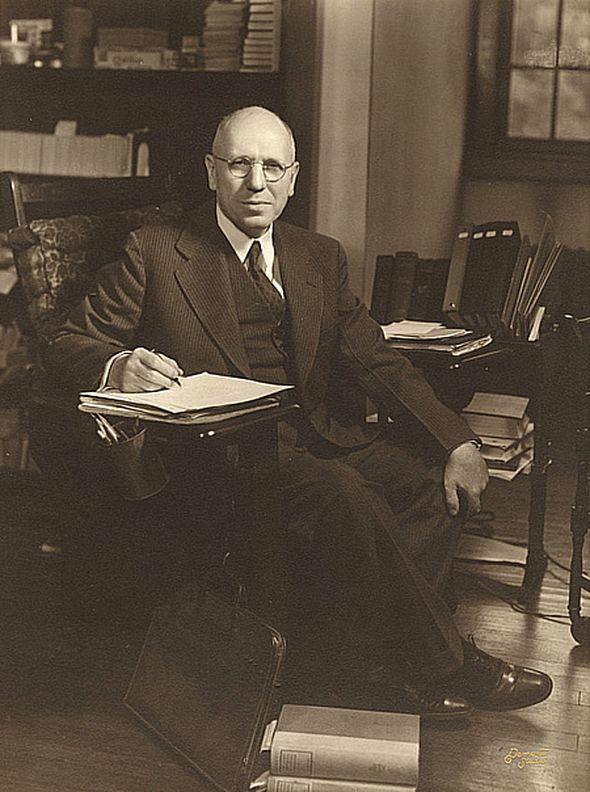

Douglas Southall Freeman late in his life. (Public Domain)

After earning a doctorate in history from Johns Hopkins, however, Freeman became not a professor but a newspaper man. Eventually he worked as a newspaper editor, writing up to 600,000 words a year of editorial copy while at the same time becoming the host and commentator on a popular radio show. To accomplish these feats, he rose daily at 2:30 a.m., went to his office, wrote his editorials and directed his employees, and returned home in the afternoon for a short nap, more writing and reading, and time with his family.

This ferocious schedule alone would have exhausted most writers, yet down through the years Freeman also produced his Pulitzer Prize-winning three-volume biography of Robert E. Lee, another three-volume work about his officers titled “Lee’s Lieutenants,” and ended with the seven-volume George Washington biography, which posthumously won him another Pulitzer. His research was extensive—his histories rested on massive investigation, including explorations of all the battlefields where Lee commanded. And like Parkman, the prodigious Freeman was a skilled writer whose fascination with the past was first sparked by boyhood imagination.

The American

Of our trio of historians,

David McCullough (1933–2022) remains most popular today. Like Freeman, McCullough won two Pulitzers, the first for “Truman” and the second for “John Adams.” Unlike Freeman or Parkman, however, who focused on specific or provincial topics, he researched and wrote about diverse topics from across the spectrum of American history, like the Johnstown Flood, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Panama Canal.

Born and raised in Pennsylvania, and an honors graduate of Yale majoring in English literature, for more than a decade McCullough worked as a journalist and editor, beginning with Sports Illustrated and ending with American Heritage Magazine. He later credited his parents and their interest in reading and history as contributors to his own pathway in life, with his work at American Heritage luring him into the past.

Author and historian David McCullough speaking in 2007. (<a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Magog_the_Ogre">Ogrebot</a>/<a href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en">CC BY-SA 2.5</a>)

McCullough dove headlong into his subjects, researching them through libraries and books, and putting his feet on the ground just like Parkman in his woodlands and Freeman in his Virginia battlegrounds. He was an exceptional writer, a talent which, when coupled with his imaginative use of evidence, beguiled readers.

The Yale University citation granting him an honorary degree notes: “As an historian, he paints with words, giving us pictures of the American people that live, breath, and above all, confront the fundamental issues of courage, achievement, and moral character.”

Through his speeches, essays, and interviews, McCullough encouraged Americans to study history, particularly that of their own country. A 2005 Brigham Young University speech titled “The Glorious Cause of America” nicely encapsulated what goods we gain by voyaging into the past:

“I hope you do this not just because it will make you a better citizen, and it will; not just because you will learn a great deal about human nature and about cause and effect in your own lives, as well as the life of the nation, which you will; but as a source of strength, as an example of how to conduct yourself in difficult times—and we live in very difficult times, very uncertain times. But I hope you also find history to be a source of pleasure. Read history for pleasure as you would read a great novel or poetry or go to see a great play.”

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc