Nuhu Dauda was on a missionary trip, about 125 miles away from his home in Plateau state, Nigeria, when he got a panicked call from his younger brother.

“He said jihadists had surrounded my home and were chanting that they would kill everyone inside,” Dauda, a 67-year-old Christian evangelist, told The Epoch Times.

The police helped rescue five family members before heavily armed men burned the house to the ground and killed a young fellow evangelist, he said.

That was in 2005.

“In the 20 years since then, I have seen our people massacred,” Dauda said. “I saw my family members, in-laws, and friends killed. I’ve carried the bodies of my own, and I buried them.”

The plight of Christians in the country received relatively little global attention until the Trump administration threatened to intervene amid a recent spike in violence, to prevent mass killings that it suggested amount to “genocide.”

The Nigerian government denies claims of religious persecution, rather framing the violence as a security crisis with “complex socio-economic and political roots” that affect people of all faiths.

But the increase in brutal attacks on Christian communities by radicalized insurgents in recent years both parallels and intersects a broader rise in violent Islamist extremism across the region.

Boko Haram and Surging Violence

Dauda grew up in peace with Muslim friends and neighbors in the country’s fertile Middle Belt region. But everything began to change in about 2001.

“It was so strange to us, we never knew that, to see our people killed in a community where Muslims were a minority but well armed,” Dauda said of radicalized groups that began attacking Christians. “They drove us out.”

While the threat has evolved, some observers trace the root of current violence to the rise of Nigeria’s homegrown Sunni jihadist movement more than two decades ago. That movement is synonymous with the terrorist group Boko Haram, sometimes referred to as the “Nigerian Taliban.”

Ebenezer Obadare, a senior fellow for Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, believes that all problems are downstream of Boko Haram.

“It’s a religious campaign in the sense that this is mass killing initiated by Boko Haram, a group that targets Christians, targets Muslims, targets everybody—because it sees all of them as infidels, or apostates,” Obadare told The Epoch Times.

Caskets holding the bodies of 38 Christian villagers killed by armed Fulani Muslim militants are arranged for a funeral Mass at Government Secondary School in Mallagun, Nigeria, on Sept. 30, 2021. (Luka Binniyat/The Epoch Times)

Boko Haram, which means, loosely, “Western education is forbidden,” has been designated as a terrorist organization by the United States since 2013.

It embraces a strict interpretation of Islam that uses “extremely narrow criteria to define who counts as a Muslim,” according to a Brookings Institution report.

Formed in 2002, Boko Haram began an armed rebellion against the Nigerian government in 2009 and has retained a stronghold in the northeast, as well as in neighboring Chad, Cameroon, and Niger.

Since then, a mix of violent perpetrators with shifting alliances and feuds has emerged across the north, including the ISIS terror group, al-Qaeda, and Boko Haram offshoots and affiliates, as well as armed bandits, new cross-border groups, and ethnic militias.

Terror in Nigeria

Nigeria ranks sixth on the Institute for Economics and Peace Global Terrorism Index 2025.

In the northwestern part of the country, where violence has historically been attributed to banditry, al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates have established a foothold since 2020, and “operationalized these cells since 2024,” according to a recent analysis by Critical Threats, a project of the American Enterprise Institute.

Reports of civilian killings in Nigeria vary, from 50,000 to more than 100,000 since 2009, with millions more displaced; figures from Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), a U.S.-based monitor, show that violence targeting Christians has spiked since 2020 but still pales in comparison to the “broader surge in overall political violence,” which it reports has resulted in far more Muslim deaths.

In 2021, the United Nations estimated that nearly 350,000 people had died as a result, directly or indirectly, of ongoing conflict in the country since 2009.

While estimates vary, Obadare said that “what nobody can doubt is that a lot of people are being killed—and more important is the fact that they’re being killed for a religious reason.”

U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters celebrate after fighting the ISIS terrorist group near the village of Baghouz, Syria, on March 15, 2019. The increase in brutal attacks on Christian communities by radicalized insurgents in recent years both parallels and intersects a broader rise in violent Islamist extremism worldwide and especially in West Africa. (Giuseppe Cacace/AFP via Getty Images)

Brazen Attacks Escalate

President Donald Trump in October relisted Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern,” a formal designation given to the world’s worst religious freedom offenders.

And in a Nov. 20 congressional hearing, State Department officials said they are working on a comprehensive plan to help bolster the country’s own security and counterterrorism efforts.

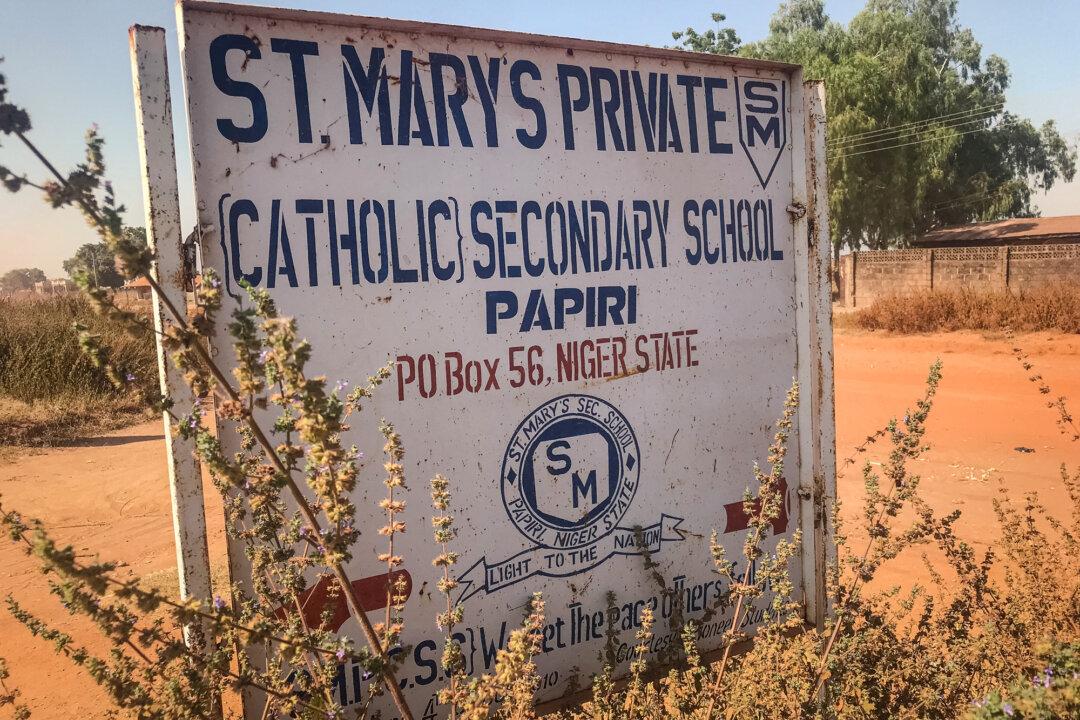

Just hours after that hearing, gunmen on Nov. 21 stormed a Catholic school in the Middle Belt, kidnapping more than 300 students and 12 teachers.

It was the fourth mass kidnapping that week, and one of the worst in the country’s history, surpassing even the 2014 Boko Haram kidnapping of 276 Chibok Secondary School girls. Last year, Amnesty International reported that more than 1,700 children have been abducted by the group in the decade since.

Kidnapping victims, according to the group, are often forced to fight, marry their captors, or are sold into sex slavery.

The wave of violence from Nov. 15 to Nov. 21 also included an attack on a Christian church during a service, during which two people were killed and 38 kidnapped, as well as the abduction of 24 female students from a secondary school and the murder of three people and kidnapping of 64 from their homes.

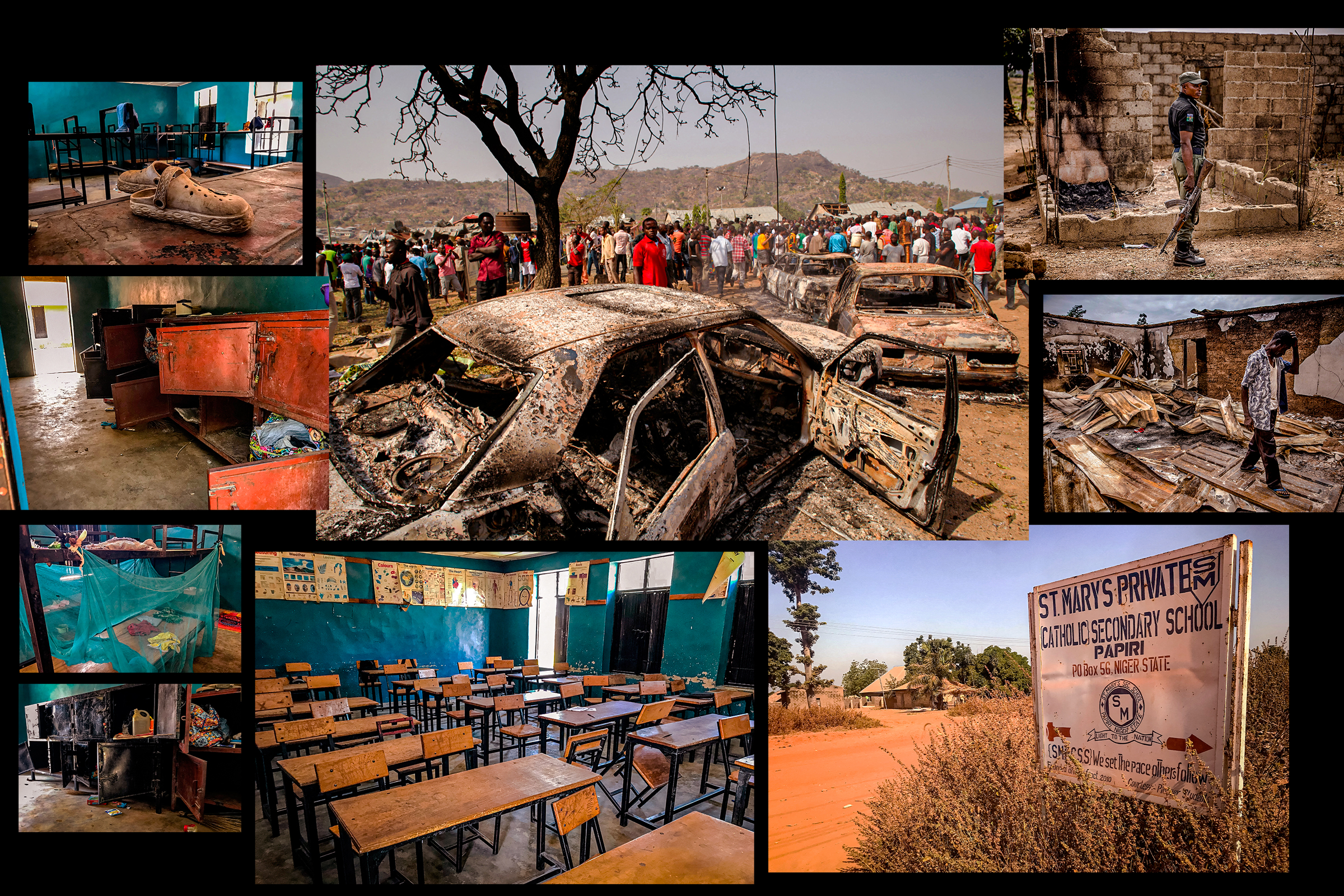

(Top) A general view of a classroom at St. Mary's Catholic School in Papiri, Agwarra local government, Niger state, Nigeria, on Nov. 23, 2025. (Bottom L) A signboard for St Mary's Private Catholic Secondary School stands at the entrance of the school in Papiri, Agwarra local government, Niger state, Nigeria, on Nov. 23, 2025. (Bottom R) A general view of empty bunk beds and scattered belongings inside a student dormitory at St. Mary's Catholic School in Papiri, Agwarra local government, Niger state, Nigeria, on Nov. 23, 2025. (Ifeanyi Immanuel Bakwenye/AFP via Getty Images)

On Nov. 24, Nigerian media reported that suspected Boko Haram terrorists abducted 12 women from Borno state and razed a village elsewhere in the state.

“We hoped the [Country of Particular Concern] designation by President Trump at the end of October might stabilize the situation,“ the Most Rev. Wilfred Anagbe, a Nigerian Catholic bishop, told lawmakers during the Nov. 20 hearing, ”but instead, it is deteriorating into one of the most lethal periods for Nigerian Christians in recent memory.”

While the government has tried to confront the terror threat, Dauda said that “this is not the confrontational war that militaries are used to.”

“They hide, attack, pull away, and cover,” he said. “The government has tried, but they are overwhelmed.”

The Nigerian government did not respond to requests for comment from The Epoch Times but recently said in a statement posted on X that its security agencies, since 2023, have “neutralized” more than 13,500 terrorists, arrested more than 17,000 suspects, and rescued more than 9,800 kidnap victims.

Fulani Militias

In May, Amnesty International reported that at least 10,217 people had been killed in attacks by gunmen in the two years since current president Bola Ahmed Tinubu was elected, mostly in the predominantly Christian Middle Belt states of Benue and Plateau.

Such attacks have drawn attention to longstanding conflicts between farmers, who are largely Christian, and Fulani herdsmen, who are semi-nomadic and predominantly Muslim in the Middle Belt.

The Nigerian government characterizes this as a land-use dispute driven by the climate, resource scarcity, and population growth.

According to Open Doors, an organization that tracks persecution of Christians, Fulani militants are responsible for 55 percent of recorded Christian deaths between 2019 and 2023.

The Observatory for Religious Freedom in Africa in July published research showing that Fulani militias accounted for 47 percent of the 36,056 civilian killings between 2019 and 2024—more than five times the combined death toll of other prominent terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram and an offshoot known as Islamic State-West Africa Province.

A group of armed Fulani militiamen pose for a picture at an informal demobilization camp in Sevare, Mali, on July 6, 2019. Open Doors, an organization that tracks persecution of Christians, reported that Fulani militants were responsible for 55 percent of recorded Christian deaths from 2019 to 2023. (Marco Longari/AFP via Getty Images)

More recently, other monitors, such as the International Bar Association’s Eyewitness Global, have noted “considerable escalation” in violence with “religious and ethnic dimension” in the Middle Belt.

And while the 2015 Global Terrorism Index ranked armed Fulani militants the fourth-deadliest terror group in the world, the Observatory notes that they have “mysteriously vanished” from international rankings despite having become “exponentially more lethal.”

Dauda, the Christian evangelist, says it’s a small number instigating and radicalizing an otherwise peaceful population.

“Most Fulanis are innocent,” he said. “Most want to live a peaceful life and take care of their cattle.”

Heni Nsaibia, ACLED’s West Africa senior analyst, told The Epoch Times the violence in the Middle Belt is “multidirectional” and can’t be reduced to a kind of religious war.

“To focus on the persecution of Christians really doesn’t capture the problem,” Nsaibia said. “That is not the main conflict—the real threat are the jihadi groups that are expanding and that larger segments of the population are falling under their influence, and they are now competing with the state.”

Some of those groups, such as Islamic State-Sahel Province, are majority Fulani, he said, but operate primarily in majority-Muslim states, meaning that their civilian victims are mostly Muslims.

As the conflict expanded across the region, Nsaibia said, the most powerful groups concentrated in Mali and Burkina Faso, where many fighters are Fulani.

“So it’s more circumstantial, but also how the state has reacted to the insurgency,” he said.

In many countries in the region, Fulani and other herder ethnicities have long been disenfranchised by the state, Nsaibia said, making them a prime target for radicalization.

‘Horrific Things’

Born a Fulani Muslim, Musa Belo converted to Christianity and became an evangelical preacher. Vocal on social media about what he calls a Christian genocide, he is currently in hiding, facing death threats from Islamists—and reprisal from the government, he says.

Belo told The Epoch Times that he typically visits many remote villages only accessible by motorcycle or on foot.

He described going to a village in Plateau state for outreach.

“We preached the gospel to them, we did medical outreach, shared Bibles, and we left. Then fast forward, this past October, we went back for a follow-up,” he said.

The whole village had been wiped out.

“You stumble on human skeletons; you stumble on a body that has not even decayed. ... Horrific things,” Belo said.

Sean Nelson, an attorney with Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), recalls visiting victims in the aftermath of a Christmas Eve 2023 attack that killed more than 200 people across mostly Christian villages in the same region.

People pose for a photograph at St. Mary's Catholic Primary and Secondary School after armed men abducted children and staff in Papiri, Nigeria, on Nov. 21, 2025. (Christian Association of Nigeria via AP)

“They went after pastors’ homes,” he said. “They went after churches first. The first village we went to, there was a pastor who, the militants came to his house on Christmas Eve, took him and his family, torched his house, walked him out behind the church, and beheaded him.”

Every witness told him that the attackers came in with machetes, shouting “Allahu Akbar,” and “We will kill Christians,” according to Nelson.

John Stewart, an American attorney and pastor who regularly travels to Africa to teach and train Christian leaders, described Nigerian communities devastated by systemic violence and displacement.

“I went to the relocation centers. These are Christians that have been driven out of their villages by Fulani Muslims, with the military looking the other way,” he told The Epoch Times.

“They’re sleeping on cement floors in churches. ... They didn’t have anything other than shovels and rakes to defend themselves.”

‘Others Who Are Behind This’

Both Dauda and Belo say Fulanis are coming to Nigeria from other countries.

“I had an encounter with one, and I am Fulani by tribe,” Belo said. “When I spoke to him, I understood that this is not Nigerian Fulani. He told me he was from Mali, and his group was headed to Benue state.”

Nigeria’s borders with Niger and Chad are easy to penetrate, he said.

“They are all using sophisticated weapons—machine guns, AK 49s, RPGs—that even our military are not using,” Belo said.

“This thing has been happening for two decades, but the Nigerian government has never brought a single perpetrator to justice.”

Dauda marveled at the sight of Fulani herdsmen carrying machine guns.

“A Fulani man takes care of his cow—that is his bank account, the future of his children. How are such innocent Fulanis operating such guns?” he said.

“It means there are others who are behind this. And I want the world to know, they have been brainwashed. Their target is to go across the nation—that’s why you hear of killings in churches in the south.”

Arms and ammunition recovered from Boko Haram jihadists are displayed at the 120th Battalion headquarters in Goniri, Nigeria, on July 3, 2019. Boko Haram, loosely translated “Western education is forbidden,” has been designated a terrorist organization by the United States since 2013. (Audu Marte/AFP via Getty Images)

The Heart of Jihadi Terror

The Nigerian government has framed attacks on Christian communities such as Dauda’s in the country’s Middle Belt or north central region as ethnic land-use disputes, as distinct from the terror of jihadists in the northeast, or the anarchy of bandits in the northwest.

But amid transnational expansion of Islamist extremism, with weapons and fighters flowing across porous borders, some analysts say such distinctions are vanishingly relevant and a distraction from the all-consuming threat of violent fundamentalism.

The Central Sahel region of sub-Saharan Africa, which includes Nigeria and stretches from the North Atlantic to the Red Sea, has replaced the Middle East as the epicenter of global Salafi-jihadist violence, now accounting for 51 percent of all global terrorism deaths, according to the Global Terrorism Index 2025 report.

Investigations by Conflict Armament Research, a British-based group that tracks illegal weapons, have suggested that the proliferation of weapons throughout the Sahel was precipitated by the 2011 fall of the heavily armed Muammar Gadhafi regime in Libya.

Data from ACLED shows that jihadist groups have entered “a new phase of expansion” in the Sahel.

In a December report, the group noted that as jihadist groups solidify their operations, distinctions between regional conflicts are giving way to a broader, singular threat.

ACLED reported that 79 percent of ISIS operations were in Africa in 2025—up from 49 percent in 2024. Islamic State-West Africa Province “controls broad swaths of territory and has killed or displaced thousands of people in Nigeria and neighboring countries,” according to the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s Counter Terrorism Guide.

A defensive trench built to protect against incursions by Boko Haram surrounds the town of Monguno, Borno state, Nigeria, on July 4, 2025. (Joris Bolomey/AFP via Getty Images)

Collaboration among jihadist groups is growing, ACLED’s Nsaibia said. In some cases, Nigerian groups have been incorporated into broader global structures such as ISIS or al-Qaeda affiliates or coordinate with regional groups across borders to share weapons, propaganda, or fighters.

As the Sahel has become the global epicenter of jihadist militancy, he said, Nigerian groups have been expanding from their historic base in the Lake Chad Basin and into coastal West Africa.

“As these groups are finding one another, they also form a sort of junction between these two very distinct conflict theaters,” Nsaibia said.

Obadare said, “We know for sure that all of these groups are united at least by one aim, which is they want to destroy the modern state as we know it.”

In neighboring Mali, jihadists are currently on the verge of overrunning the country, according to a report last month by the Soufan Center.

Sharia and Blasphemy

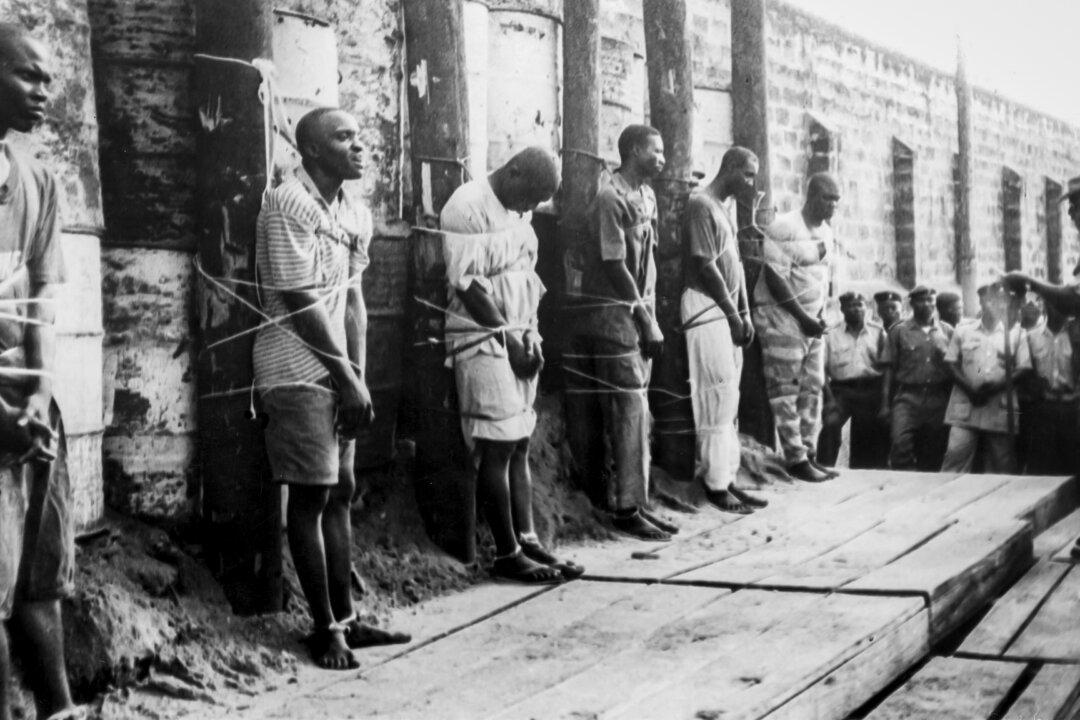

In the years following Nigeria’s 1999 transition to a constitutional democracy, 12 northern states have reintegrated Islamic criminal law. In theory, sharia applies only to Muslims, but in practice, human rights advocates argue, it is used to justify mob violence and state-sanctioned capital punishment.

“Death penalty blasphemy law in the 12 Northern States is an outrageous thing,” Nelson said.

The ADF intervenes on behalf of individuals facing blasphemy and apostasy charges in Nigeria’s sharia courts.

“It is one of only seven places in the world with a law like that,” he said.

In 2024, Amnesty International reported an escalation of mob violence across the country, including killings related to blasphemy accusations in which victims have been lynched, stoned, tortured, and burned alive.

“The apparent encouragement of killings for blasphemy by religious leaders creates an environment in which mobs feel entitled to take the law into their own hands. Meanwhile, government officials rarely publicly condemn mob violence for blasphemy,” the group reported.

Six men condemned for armed robbery stand before their execution by firing squad at Kirikiri Prison in Lagos, Nigeria, on Feb. 21, 1998. Since Nigeria’s 1999 return to civilian rule, 12 northern states have reintroduced Islamic criminal law, known as sharia, which human rights advocates say has been used to justify mob violence and state-sanctioned capital punishment. (AFP via Getty Images)

‘A Religious Element’

Obadare said the conversation about violence in Nigeria has become increasingly muddied; there used to be a consensus that the threat was fundamentalism, he said.

“The idea that Islamist insurgents should not be described or portrayed as what they are because you don’t want to offend mainstream Muslims. ... I find [this] condescending to mainstream Muslims,” he said.

“The more Boko Haram says our aim is religious; we want to replace Nigeria with an Islamic state; we hate democracy; unbelief is the problem ... the more people on the other side double down and say, ‘Nope, you don’t know what you’re talking about. It’s climate change, it’s got nothing to do with religion.'”

Despite the constant threat, Dauda said he wouldn’t think of living anywhere else.

“We are asking God to intervene,” he said. “That’s why we even have an opportunity to tell you about this.”