The U.S. Department of Education has issued updated guidance clarifying the right of students and teachers in public schools to pray and engage in other religious expression.

Released on Feb. 5, the guidance reaffirms existing constitutional protections for teachers and students, saying they can pray at school as an expression of individual faith, so long as they are not speaking or acting on behalf of the school.

The document also reminds public school administrators that they must treat religious speech the same as secular speech. That includes situations such as students expressing religious views in class assignments.

“If a public school teacher called a student’s religiously based view that marriage should be between one man and one woman ‘despicable’ and lowered the student’s grade in response, that teacher would demonstrate religious hostility and violate the student’s constitutional rights,” the guidance states.

That principle applies to religious student organizations, the department said. If a school provides support, recognition, or access to secular clubs, it must extend the same support to religious clubs on a nondiscriminatory basis.

Schools may still regulate religious expression when it crosses the line into a “substantial invasion” of the rights of others or a “material disruption” of normal school operations, according to the document. A student, for instance, may not pray out loud during math class in a way that prevents others from learning, but administrators must address such disruptions the same way they would address comparable nonreligious speech, applying rules consistently.

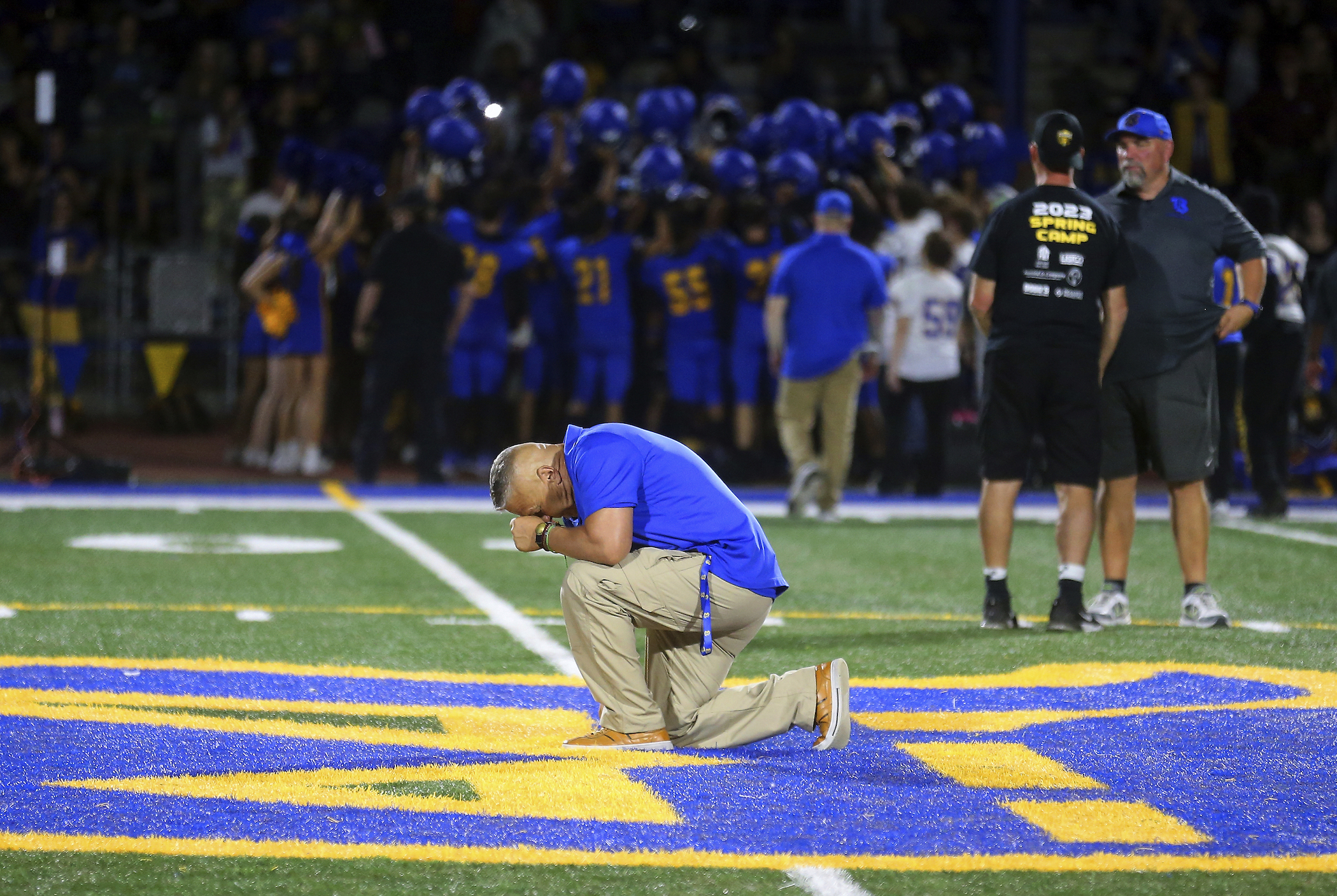

The guidance cites the Supreme Court’s decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District three years ago, in which the Court held that a public school district in Washington state should not punish a high school football coach for praying on the 50-yard line after a game—a practice that students often joined. The 6–3 majority concluded that the coach’s postgame prayers were his personal expression of faith and that students were not required or coerced to participate.

The document also addresses the Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling in Mahmoud v. Taylor, which involved families from different religious backgrounds who objected to a mandatory public elementary school curriculum endorsing same-sex unions and transgender identities. The Court sided with the families, holding that a public school “burdens the religious exercise of parents” when their children were subject to instruction that directly contradicts the parents’ religious beliefs.

According to the Education Department, the updated guidance is meant to help schools align their policies with Kennedy, Mahmoud, and other Supreme Court precedents interpreting the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause.

“Our Constitution safeguards the free exercise of religion as one of the guiding principles of our republic, and we will vigorously protect that right in America’s public schools,” U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon said in a statement.

The 2026 guidance replaces a 2023 version issued under then-Education Secretary Miguel Cardona. Both documents rely on the same constitutional basis and discuss the implications of the Kennedy decision, but they differ in emphasis.

The now-rescinded Cardona guidance focused heavily on ensuring that teachers did not impose their religious views on students while engaging in personal religious expression. For example, it stated that school employees may not “compel, coerce, persuade, or encourage” students to join in their prayer or other religious activity. It also specifically instructed that if a school has a moment of silence or quiet period during the school day, teachers and other employees may neither encourage nor discourage students from praying during that time.

The new McMahon guidance, by contrast, places greater emphasis on the requirement that schools not discriminate against religious viewpoints. It devotes extensive attention to Mahmoud, arguing that the principles articulated in that case—though not directly related to school prayer—have broad implications for how schools handle religious speech and parental rights.

“This is not the familiar but legally unsound metaphor of a ‘wall of separation’ between religious faith and public schools,” the 2026 guidance declares. “It is rather a stance of neutrality among and accommodation toward all faiths, and hostility toward none, deeply rooted in our nation’s history, traditions, and constitutional law.”