As tens of millions of children head back to school, parents and teachers are grappling with questions about how much artificial intelligence (AI) is too much.

The education system will be one of the primary laboratories for the global AI experiment, according to author Joe Allen.

“Schools—to the extent that they either mandate or encourage the adoption of AI—are going to be massive petri dishes in which we’ll find out whether it’s better to maintain traditional cultural norms, or if we turn every child possible into a cyborg,” he told The Epoch Times.

No one knows what the long-term effects will be, said Allen, who authored “Dark Aeon: Transhumanism and the War Against Humanity.”

In the same way that popular technology, such as TV and portable transistor radios, broadcast the music and message of subculture movements that influenced a generation of children to break away from their parents’ cultural norms during the 1960s, he said, AI could also affect “a generation of children who are acclimated to interacting with machines, basically as if they were people.”

Joe Allen, author of “Dark Aeon: Transhumanism and the War Against Humanity,” discusses the potential pitfalls of AI in the classroom. (Courtesy of Dan Fluette)

Some teachers already believe that AI will have a negative impact on academic integrity, according to a 2024 poll of 850 instructors published by The Wiley Network. Nearly half, or 47 percent, of more than 2,000 students surveyed said cheating was already easier with AI.

Allen said many assignments that students turn in either bear a striking resemblance to each other or don’t sound like they’re written in the student’s own voice.

Even college students admit that AI is dumbing them down. In a 2024 study published in the European Research Studies Journal, 83 percent of mostly college-aged students surveyed expressed concern that AI weakens the ability to think independently.

According to a 2023 survey of 1,000 U.S. college students by online magazine Intelligent, nearly one-third said they used ChatGPT to complete written homework, with almost 60 percent saying they used it for more than half of their assignments. The poll found that of these students, three out of four believe that it is cheating but use AI anyway.

A majority of parents in several surveys have expressed concern about the effects of AI use on their children.

A study by DoodleLearning in 2024 found that roughly 80 percent of 1,000 parents with school-aged children in school were worried about the impact of AI on education. Parents surveyed were also worried about privacy, data security, and plagiarism.

The Department of Education in July encouraged schools to teach children how to use AI responsibly and to use it to “personalize learning” for “students at all levels.”

‘Your Brain on ChatGPT’

Shannon Kroner, a clinical psychologist, educational therapist for more than 20 years, and children’s book author, said she believes that AI affects critical thinking and “dehumanizes both the teacher and the child.”

Shannon Kroner, an educational therapist and children’s book author, worries that the use of AI in schools could hinder children’s critical thinking skills. (Courtesy of Shannon Kroner)

Kroner, who has taught high school biology and college humanities courses, said AI reduces education from healthy learning based on teacher-student relationships to a cold transaction.

“AI creates an intellectual laziness in both the teacher and the student, and ... an erosion of curiosity, stunted cognitive development, and reduced problem solving. It weakens logic and reasoning,” she told The Epoch Times.

“The students aren’t going to need to do the research and dig through the studies needed in order to defend their perspective on whatever it is that they need to prove.”

Educators are consulting AI more frequently to develop lesson plans because it makes their jobs easier, but it will eventually disempower them in their roles as teachers as students rely more and more “on what a robot says.”

“We’re really going to lose that teacher-student connection,” she said. “The more it becomes natural to use AI, students will just turn to AI for answers, and it won’t matter what the discussion is between the teacher and the student. The discussion will probably end up being obsolete. There won’t be a discussion.”

Allen and Kroner are both concerned about the erosion of critical thinking skills in the classroom.

A recent MIT study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” looked at whether AI harms critical thinking abilities.

The study correlated cognitive and neurological data from 54 students, ranging in age from 18 to 39. It used electroencephalography to record the brain activity. The students were divided into three groups—one using OpenAI’s ChatGPT, another using Google’s search engine, and the third using nothing but their brains—and were tasked with writing several essays.

The study found that ChatGPT users, or large language model AI users, had the lowest brain engagement and often resorted to cut-and-paste answers.

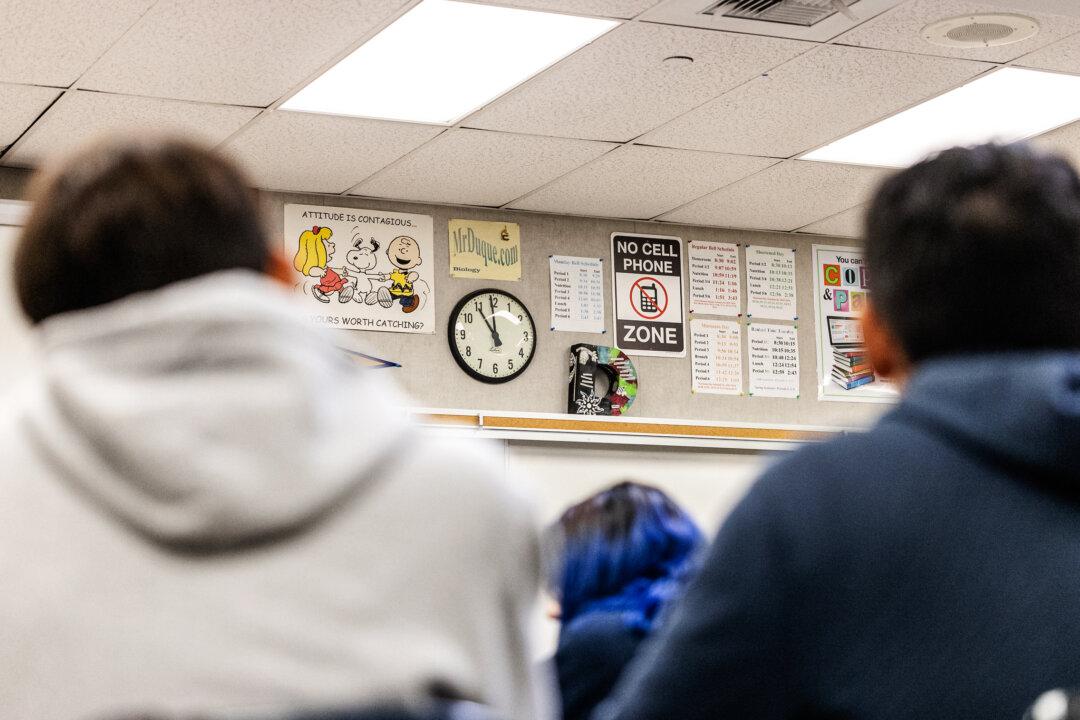

A Los Angeles Unified School District campus in Los Angeles on Jan. 8, 2024. Schools are increasingly using AI for automated grading, lesson planning, quizzes, and virtual tutoring through chatbots. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Over four months, large language model users “consistently underperformed” at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels. These results raise concerns about the long-term educational implications of [large language model] reliance and underscore the need for deeper inquiry into AI’s role in learning,” the study concluded.

The group using AI was “completely bored” and showed lower memory recall, with less brain activity, especially in the hippocampus, where memories are formed, Allen said.

Essentially, he said, the study confirms that “AI makes people stupider.”

“If you rely on a machine to do your thinking for you, you won’t think as well,” he said.

Mental Health Concerns, Artificial Friends

AI’s effects on humanity likely won’t be known for years, much like the long-term effects of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Allen said.

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, work from home, and virtual learning push that resulted solidified the trend away from in-person interaction.

Extensive use of social media, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, has been widely identified in studies as a factor in mental health problems for youth. Kroner is worried that adding AI to the mix could worsen the problem.

AI companies are promoting robotic artificial friends and chatbots as companions for children who were isolated from their real friends during the COVID-19 pandemic, and now people are turning to AI for therapy, she said.

The technological move toward humanoid robots and encouraging artificial friends for children raises other questions such as whether such AI products can alleviate loneliness in shy or socially awkward children, or if it will further alienate and isolate them from other children and healthy physical activities such as playing outdoors and participating in sports.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, prescriptions for antidepressants for adolescents and young adults were already rising before the COVID-19 pandemic, but from March 2020 onward, they surged more than 60 percent faster.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times, Getty Images)

Kroner said she fears that AI will destroy the innocence of childhood, including through the sexualization of chatbots, including X-based chatbot character “Ani.”

AI systems also come with risks to privacy for children entering personal data into these systems, she said.

“Who’s collecting all the data and can that data eventually be exploited?” Kroner asked. “Who is holding onto that data?”

While the phrase “garbage in, garbage out” still applies in computing to some extent, AI is vastly different, Allen said. In classical computing, “garbage in, garbage out” meant that “if you threw a bunch of garbage into a rules-based program, you could kind of predict the garbage that would come out from the garbage that came in,” he said.

But you can throw “garbage and gold” into large language models, and they can select the gold from the garbage, Allen said. Unlike basic search engines that serve as simple database lookup tools, AI has a mind of its own in the sense that it can navigate its own path through data within bounds as users ask questions, allowing it to uncover a lot of useful information that otherwise may have been buried, according to Allen.

In some ways, AI functions like a human brain with a degree of freedom and randomness, but it does so in a “very alien way,” he said.

AI is also prone to confabulation known as “hallucinations” that present false or misleading information not based on perceptual experiences, and it does so in a convincing manner.

“Just the hallucination rates alone should be enough to alarm parents that it’s not going to be the super genius that people like Sam Altman are promising,” Allen said.

In company tests, OpenAI’s latest 03 and 04-mini models hallucinated 51 percent and 79 percent of the time. And in a 2024 study evaluating the use of AI in the legal profession, hallucination rates ranged up to 88 percent.

Allen pointed to an example of ChatGPT’s latest 4.5 version abandoning guardrails meant to prevent certain discussions and instructing users how to conduct sacrifices to Molech, an ancient deity historically associated with child sacrifice.

There have been many other cases of people breaking through AI guardrails. In one recent example, in early July, the Grok chatbot unexpectedly generated and spread a series of anti-Semitic posts.

“Inherent in the technology itself is an element of randomness. The non-deterministic nature of the system means that beneath those guardrails is turning a kind of id, and the guardrails function as a kind of super ego,” Allen said. “It doesn’t take a skilled user to get past a lot of those guardrails. You just need a few simple tricks.”

Illustration of the generative AI chatbot Grok, in this file image. In early July, the chatbot unexpectedly produced and spread anti-Semitic posts, raising concerns about vulnerabilities in AI guardrails. (Riccardo Milani/Hans Lucas/AFP via Getty Images)

Protections for Kids

As long as governments, schools, and companies are willing to experiment with AI technologies with no real knowledge of what the outcomes will be, there is good reason to be skeptical of AI in the classroom, Allen said.

Some teachers are advocating the return of oral exams, Blue Book tests, or the use of word processors with limited internet access, Allen said.

“At this early stage of the AI experiment, that’s going to be a net positive for those who do,” he said.

Allen said it is possible for schools to create sanitized, academic-only AI systems.

A student raises her hand during class at Tussahaw Elementary School in McDonough, Ga., on Aug. 4, 2021. (Brynn Anderson, File/AP Photo)

“That’s going to be the norm going forward,” he said. “I wouldn’t necessarily worry about your Educational AI going off the rails and giving you passages from the Marquis de Sade.”

Allen said there are three levels of resistance when it comes to protecting children and their critical thinking abilities: personal choice, institutional policies, and political or legal action.

At the personal choice level, parents living in the United States and other “free-ish societies” will be faced with the question of how to raise their children, he said.

“Parents have the choice to subject their children to this experiment or not to put kids into schools that are going full-digital or even hybrid,” Allen said.

At the institutional level, schools can choose whether to fully adopt AI or implement some type of partial or hybrid system, he said.

“Those will be critical decisions going forward,” Allen said. “This is an experiment, so these are going to be basically control groups.”

So far, the prospect of restricting AI in U.S. classrooms through the political and legal systems “is not looking very hopeful” beyond the state level, he said, but resistance to AI is building among coordinated parent groups in the United States and other countries.

Australia, for example, seeks to build massive data centers and open up data from Australians for use in training AI, but its policies to restrict smartphones in schools and require age verification for social media are “directionally correct,” Allen said.

“You actually have whole countries such as Australia which are doing everything possible to restrict the digital exposure on young children—everything from banning cellphones in schools to raising kids completely digital free,” he said. “So the control group is healthy.”

Kroner speculated that AI will cause some children to further reject the authority of teachers and parents. She encouraged parents to give real-world examples when children raise questions.

“The children can listen and give feedback and kind of take the AI out of it,” Kroner said, stressing that more human interaction and conversation are what’s missing in today’s world, not “canned responses at our fingertips.”

There is also the possibility that children trained to look at AI systems as superior teachers—especially in places in which good human teachers are sparse—could outperform those who don’t use AI, Allen said.

“And, some of that is due to the fact that digital culture is so predominant that to adapt means that you are basically adapting to ever evolving norms that are pushed from the top down to the population,” he said.

“So it’s not like some natural evolution. It’s not Darwinian in the original sense, but it is an open question what the outcomes are going to be. We just simply don’t know. It’s an experiment.”