CODY, Wyo.—AJ Richards comes from a fifth-generation ranching family but had always considered himself the “city-slicker cousin.” However, he figured that he would eventually make his way back to the land.

After serving in the military and pursuing a series of unrelated ventures, he began working for his family’s beef ranch and started seeing a disconnect between Americans and the food they consume.

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the problem well, he said. “We had empty store shelves, but we had all these fat cows. We’d become so separated from our food supply.”

He ruminated on supply chain weaknesses exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and began to think of famine as a “when not if” scenario. Then, he had a vision.

“I was in my mom’s basement in Arizona, pouring concrete, working at Walmart at night, and selling beef on the weekends,” he said. “I always wanted to be a rancher. I was trying to pursue these other things and make money to get into agriculture.”

He began dreaming of a familiar scene.

“God was showing me the face of a man in Iraq that we used to take packages to, to feed him,” Richards said, recalling his deployment in the country. He pulled up an image on his phone of the man and his children on a bone-dry dirt road.

“But in my dreams, I was him, watching other men feed my children,” Richards said.

That primal fear of not being able to feed his own children led him to an idea.

“It was like a download from God,” he said. “I thought, someone should be the Airbnb of local food.”

After a few years of thinking and talking about the idea, he landed initial investment and launched From the Farm in March 2024. The idea is to connect small, family-run producers directly with consumers and net them full retail value for their products. Ultimately, he hopes to grow big enough to link buyers with producers on a hyperlocal scale.

So far, he has almost 100 producers across 35 states, selling mostly meat, but also produce and some niche products.

“We’ve even got someone on there that sells donkey milk, which I’ve never heard of,” he said.

To Richards, the mission is urgent. Consolidation of the meat industry, the continued decline of small family farms and ranches, and America’s increasing reliance on imported food are threatening our food supply, he said.

He has his work cut out for him. Perfecting the software involved is the biggest hurdle, and he has competition. Other e-commerce platforms such as Farmish, Local Line, Barn2Door, and Red Hen are swimming in the same waters.

AJ Richards works at his home outside Cody, Wyo., on Oct. 14, 2025. In 2024, he founded From the Farm, a platform connecting small family producers directly with consumers so that farmers can earn full retail value for their goods. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

And there is a balance to strike. Richards wants to get big enough to become hyperlocal, so that families can connect with farmers close to home. He wants farmers to receive the whole retail value of their sales, meaning that he will not take a commission, while keeping prices low enough to retain customers. And he wants to avoid selling out: no venture capital money and no corporations, just family operations.

He said he uses Airbnb as a parallel example because its platform aggregates millions of consumers “so the short-term rental folks don’t have to do that marketing on their own.”

“They took care of all the logistical challenges in the middle—the booking, the billing, the insurance,” he said.

“We would not have a short-term rental market if those technologies never came around, not at the scale we do.”

Tinfoil Cowboy

Richards is a kinetic communicator who meanders tangentially and sometimes elliptically, but who often alights on slogans and anecdotes. “Shake the hand that feeds you” is a favorite phrase.

He is learning to interact with media, big money, and Washington players, and has a natural talent for sound bites.

During a drive out to a remote part of northern Wyoming to visit a friend’s ranch, he fielded calls from government officials and nonprofit behemoths, discussing everything from event planning to multibillion-dollar funds, a federation of veteran-run farms, and whether or not water buffalos or bull meat is the next big thing.

A man of many hats, lately he has been partial to one: a silver cowboy hat meant to telegraph the irony of true so-called conspiracies about farming, ranching, food supply, and security.

“I started talking about the potential of famine if we don’t do things differently—this was during the Biden administration—and I was called a conspiracy theorist,” he said. “I said, ‘OK, well I’m just gonna reappropriate the tinfoil hat.”

Online and at events, the gambit has gotten him noticed, and now he is in regular contact with Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, weighing in on what he sees as the most pressing problems facing U.S. food producers.

AJ Richards works at his home outside Cody, Wyo., on Oct. 14, 2025. Richards said the fear of not being able to feed his own children led him to start From the Farm. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Famine is easy enough to imagine, he said, pointing to heavy consolidation in the meat industry, which edges out smaller producers and makes the supply chain vulnerable.

In 2023, the 11 largest beef plants processed 46 percent of all cattle and the 14 largest pork plants processed 60 percent of all hogs, according to a Department of Agriculture (USDA) report. There were 1,012 federally inspected slaughterhouses at the beginning of 2024.

“If you want to cripple and starve America, burn ‘em down,” he said. “Slaughterhouses are soft targets.”

An experience during the COVID-19 pandemic spelled it out for him.

His family ranch had been selling beef directly to consumers, mostly local ones. The government response to the COVID-19 pandemic initially triggered a surge of orders, but slaughterhouses were suddenly less available.

“We went from easy access to all of a sudden a year-and-a-half wait,” Richards said. “It was pretty eye-opening.

“We were driving all over the state of Utah to get our cattle into any facility that had a cancellation.”

The result was changes in packaging and quality.

“So now it looks like we have no idea what we’re doing,” he said.

The ranch ended up shutting down its direct-to-consumer sales.

By default, Richards became the plant manager of a small slaughterhouse in Cody, Wyoming, that his business investors purchased in order to connect with regional ranchers.

“That was really the last piece of market research that I need to see this thing holistically, at least on the meat side,” he said. “What I’ve learned is that every single farmer and rancher told me the same thing: We must have a competitive marketplace—which is what I was designing, so I knew I was on to something. I just needed to figure out all of the details.”

On their own, small producers cannot compete with the handful of corporations that controls the meat industry.

But if you increase the domestic herd and build more local or regional supply chains, he said, you will have “a reason to build a processing facility.”

“You have the volume you’ll need and [small producers] can stay viable,” he said.

A farm outside of Ten Sleep, Wyo., on Oct. 14, 2025. Richards said heavy consolidation in the meat industry is edging out small producers and leaving the food supply chain vulnerable enough to make famine conceivable. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

‘Nobody Wants a Handout’

Richards said that among the family producers he interacts with, the sentiment is that “nobody wants a handout.”

“They want a fair shot, they want a fair market,” he said.

When asked how small operations can compete with the massive supermarkets in urban areas, he said the key is taking some of the burden (such as marketing) off of small family farms.

More ranchers are turning to direct-to-consumer sales in order to survive, but it is hard to thrive.

The ranchers or farmers Richards knows who have grown their operations and reach are the exceptions, those somehow able to put time, money, and energy into marketing and sales in addition to growing the food and getting it where it needs to go.

“You might have enough kids at home that you can spread the workload, but if you don’t, it’s really hard to take all of that on,” he said. “So if you can take the burden of marketing off their plate, which is very expensive and challenging because the algorithms are constantly changing, that’s a significant boost.”

The growing popularity of homesteading today means that it is an opportune time for the government to help amplify the message.

Richards proposed a nationwide marketing campaign to Rollins, noting that it could take the form of grants for educational organizations that have big audiences.

“Government is never great at executing those kind of things, so I don’t think they should be the ones doing it,” he said.

Rather, he said, organizations that know how to use social media to reach and educate consumers should have access to capital. This would allow them to create this messaging on a mass scale, to reeducate consumers on how and what to buy from their local farms and ranches.

“The government should teach consumers how to go back to the source; they should promote this on a scale like they did victory gardens during World War II,” he said of the iconic USDA-backed campaign urging Americans to use their properties to produce food.

A World War II victory garden poster. The Department of Agriculture-backed campaign urged Americans to grow food on their own properties during wartime. (Miller, J. Howard/CC0 1.0)

In 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt urged all Americans to grow victory gardens, noting that their “tremendous” harvest “made the difference between scarcity and abundance,” with USDA reporting that 42 percent of the nation’s produce came from home gardens in 1943.

Shrinking Herds

Today, with the closure of the southern border to cattle imports due to the New World screwworm, and containers of beef coming from farther afield, there is potential for critical shortages and supply chain disruptions, Richards said.

And with only 1.9 million farmers and ranchers in the country and nearly 350 million people to feed, he said he believes the only way to fix the food system is to add more acreage, more producers, and an inward focus to stabilize the U.S. food system.

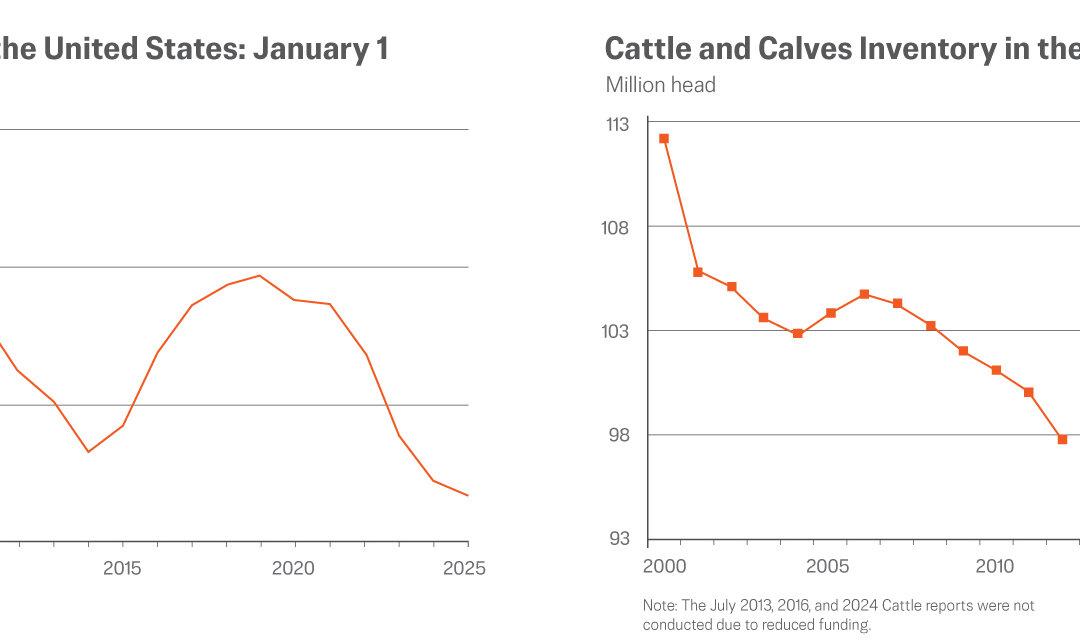

In particular, Richards is concerned with the decline of the country’s domestic cattle herds, which have fallen to their lowest level in more than 70 years. In January, total inventory was 86.7 million, the lowest level since 1951. As of July, the USDA had reported an increase to 94.2 million.

Some industry observers argue a shrinking herd is not all bad news, as it means reduced greenhouse gas emissions and better prices for ranchers.

Those benefits are part of “a conversation” that needs to start, according to a July article by Ben Lilliston, director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

“The drop of the U.S. cattle herd has not been the result of an intentional policy, and in part has been driven by climate change itself,” he wrote. “But the short-term outcomes, better prices for ranchers and lower [greenhouse gas] emissions, could be the basis for a conversation about what a future policy framework might look like.”

Current conditions are putting small and midsized operations out of business—about 20,000 annually over the past five years—and consolidating power in the hands of the top meatpacking companies.

“To rebuild a herd takes seven years,” Richards said. “Old-timers are selling out because the prices for beef are so high. We need to incentivize the regrowth of our herd.”

To that end, he has been working with Rollins’s office to advocate for expanded grazing on public lands.

Cows roam the ranch of RC Carter and Annia Carter outside of Ten Sleep, Wyo., on Oct. 14, 2025. Rancher AJ Richards is concerned with the decline of the country’s domestic cattle herds, which have fallen to their lowest level in more than 70 years. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Why Smaller Producers?

Restoring cattle grazing on federal lands can empower independent ranchers to include regenerative practices and to raise high-quality, humanely handled livestock, Richards said.

Spreading production across a more diverse pool of farmers and ranchers throughout the country strengthens food security by making the supply resilient to disease, climate, and trade impacts.

It also means the animals are more likely to be treated better. It is no secret that the massive consolidation model of commercial farming in the United States necessitates confining animals to ever tighter spaces in which there is a higher risk of disease and a greater need for antibiotics, he said.

Currently, Richards does not require producers on his platform to be “organic” or “regenerative,” but he thinks things will go that way over time.

“My hope is that as we scale, the guys that are doing sustainable or regenerative practices will influence their neighbors just by being neighbors,” he said, noting the majority of first-generation producers are regenerative or sustainable because that is how they are introduced to the trade.

“But the generational producers, if you tell them what to do, you just put up an iron wall and they’ll never consider it,” he said.

Maybe, he said, these practices need to be incentivized.

AJ Richards works at his home outside of Cody, Wyo., on Oct. 14, 2025. Richards and other advocates are hoping that the Trump administration will help efforts to reimplement mandatory country of origin labeling for beef and pork. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Consumers value grass-fed or pasture-raised beef because of its nutrition and because they want the animals to be allowed to live a natural life before they are slaughtered. They pay a premium for meat not treated with antibiotics or raised in feedlots the size of small cities.

But currently, according to the most recent data available, grass-fed beef makes up only about 4 percent to 5 percent of the overall U.S. beef market, and 75 percent to 80 percent of that consists of cheap imports.

The United States is the world’s largest producer of beef, but also its second-largest importer; between 2017 and 2021, Mexico and Canada supplied an average of 48 percent of America’s beef, according to the USDA.

Richards and other advocates are hoping the Trump administration will help efforts to reimplement mandatory country of origin labeling for beef and pork, after Congress exempted the products to conform with World Trade Organization rulings in 2015.

But ultimately, Richards said, connecting consumers with farms through websites such as From the Farm beats labeling.

“Our whole point with the platform is informed consumer choice,” he said. “If you can go right to the source and ask them directly, then the label doesn’t matter.”