“There are two stories here,” begins Sotiris Theodorou. He is sitting under a formidable winter sun, outside his waterfront bar on the Greek island of Chios.

We are about a mile from the tiny village of Volissos, as some legends have it, the birthplace of the ancient Greek poet Homer.

Theodorou is both a hard man to find—the only way to get here is by boat or a hair-raising mountain road—and an easy one, having recently become the unlikely face of a battle over the future of the island.

One story, said Theodorou, aqua eyes glimmering, “is about Europe’s need to produce antimony and other raw materials, because China has cut them off.” He is referring to the communist regime’s recent clamp-down on critical minerals exports—and to a controversial plan, temporarily on hold, to mine for antimony in northern Chios.

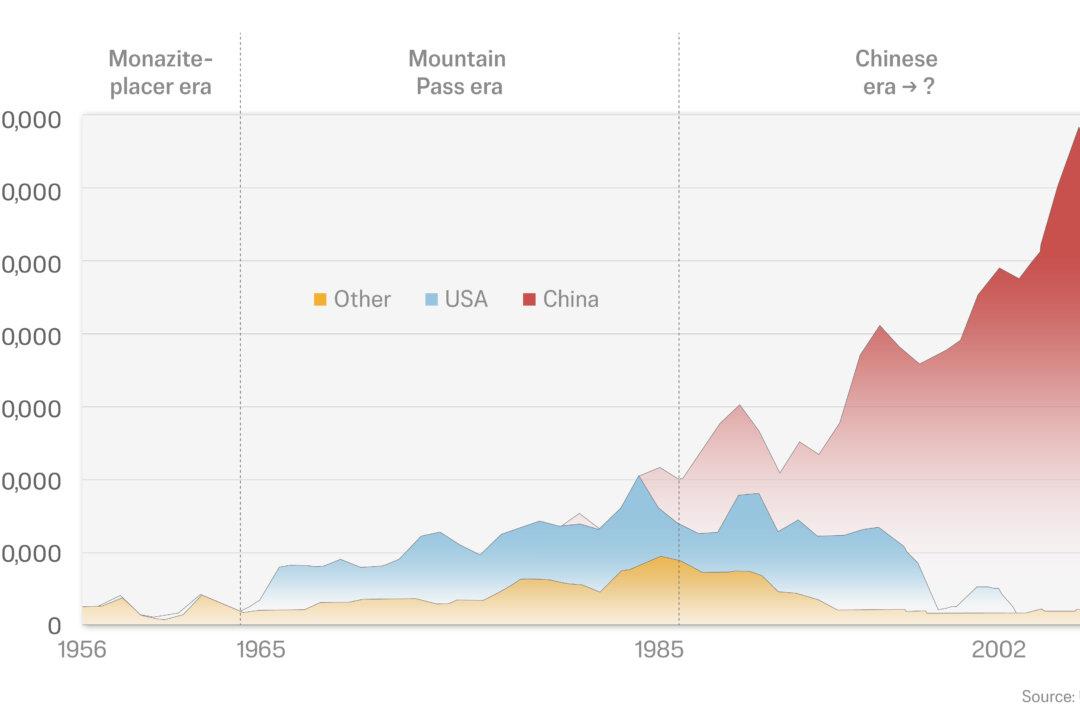

The metalloid, an indispensable input for defense, artificial intelligence and “green” technologies, is in high demand as Western countries seek to end dependence on China, which for decades controlled nearly 90 percent of production.

A chart shows rare-earth element production between 1956 and 2008, based on data from the U.S. Geological Survey. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

While both the United States and Europe are investing billions to ramp up domestic production of antimony and other critical minerals, neither currently has viable large-scale antimony mines.

Greece has significant, largely unexploited deposits, making it an attractive frontier.

The other story Theodorou tells is about a fire that, over the summer, ravaged nearly 30,000 acres of pristine land in Northern Chios, blackening mountain tops and villages and hillside after hillside of terraced olive groves.

The vast majority of the burn area overlaps with the proposed antimony industrial zone, and with a nature preserve. Since 1996, most of the island’s north side has been designated a protected “Natura 2000” site by the European Union.

Sotiris Theodorou stands in a doorway in Limanáki, Greece, on Nov. 14, 2025. Theodorou and a handful of residents in isolated, depopulated villages succeeded in forcing the government to halt a proposed large-scale antimony mine. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Just months before the fire, an unlikely opposition movement—started by Theodorou and a handful of people in isolated, depopulated villages—had succeeded in forcing the government to stop the proposal.

“The government thought they were done, ready to start [mining], and then we started to speak up,” he said.

Thousands of people, along with the island’s major industry groups and businesses, signed a petition opposing the mines.

Now, Theodorou worries, damage from the fire and what he characterizes as a neglectful municipal response—“the planes didn’t come, the firemen did nothing”—will make it easier to overcome community opposition when the project is inevitably resurrected.

Officials did not respond to inquiries from The Epoch Times regarding antimony mining or the fire response.

A wildfire moves toward the village of Ágios Geórgios Sykoúsis on the island of Chios, Greece, on June 23, 2025. The blaze burned nearly 30,000 acres of land in northern Chios, much of it overlapping with a proposed antimony industrial zone. (Dimitris Tosidis/AFP via Getty Images)

Greece’s Conundrum

Interests in mineral exploitation across the Mediterranean will only intensify as Europe seeks to wean itself from Chinese imports and expand mineral extraction to meet its own 2050 carbon neutrality goals.

In this era, Greece has the potential to emerge as a production powerhouse, with vast reserves of many critical minerals, including gallium, bauxite, and germanium, and potential for rare earth production.

Demand for critical minerals is expected to more than double by 2030 and to triple or quadruple by 2050, according to projections from the International Energy Association.

The minerals are crucial for everything from bullets to cars, renewable energy to smart phones and computers. Meanwhile, China has weaponized its near-total monopoly on processing, while pushing a global “green” agenda for which it has positioned itself as an indispensable supplier.

As the West’s new Cold War with China intensifies, the race to locate, extract and process these materials will increasingly unfold in forgotten corners of the globe, like Chios, where national security imperatives collide with environmental ones.

Mines were once the engine that powered ancient Greece. Athenian silver, pulled from rich deposits near the port of Lavrio, funded a maritime dominance credited with no less than the rise of Western civilization.

Atop their ruins sit remnants of successive revivals—abandoned factories, shafts and sprawling tunnels from the 19th century and 20th centuries.

(Top) An old mining facility sits near the port of Lavrio, Greece, on Nov. 12, 2025. Greece’s largely unexploited antimony deposits have drawn interest as Western countries seek to reduce reliance on China. (Bottom L–R) Mine shafts at a former mining facility near the port of Lavrio, Greece, on Nov. 12, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Elsewhere, there are stark reminders of modern failure, where once profitable operations became lasting symbols of state mismanagement.

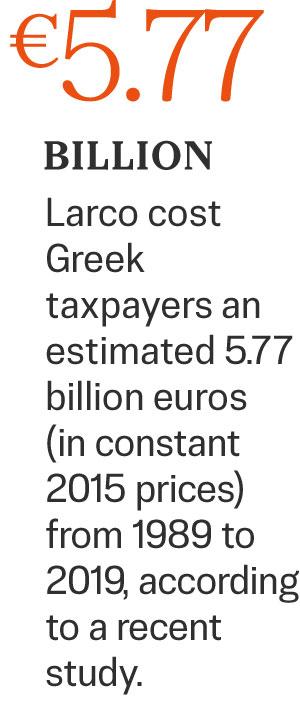

In Central Greece, an abandoned smelting factory once operated by Larco, for decades Europe’s largest nickel producer, remains perched on an outcrop over the Aegean. The majority-state-owned company collapsed in 2020 after three decades of worsening financial woes left it defunct and indebted.

Larco cost Greek taxpayers an estimated 5.77 billion euros (in constant 2015 prices) from 1989 to 2019, according to a recent study from the Center for Liberal Studies, a thinktank based in Athens. Hundreds of millions in “illegal state aid,” according to the European Commission, kept the lights on but could not forestall an inevitable demise.

As multinational mining operations expand across the country once again, Greece faces a new war: externally, against China’s malign stranglehold on the future of technology, and, internally, over how its natural resources—minerals, beaches and forests alike—will be used.

The transition to “clean” technology often presents novel ecological conundrums; like many extractive industries dominated by China, antimony mining is notoriously dirty business.

On Chios, antimony mines abandoned a generation ago have already left a haunting legacy.

(Top) A former nickel smelting plant sits abandoned in Larymna, Greece, on Nov. 12, 2025. Greece’s vast reserves of critical minerals position it to become a production powerhouse as Europe seeks to reduce reliance on Chinese imports and meet its 2050 carbon neutrality goals. (Bottom) An old mining facility sits near the busy port of Lavrio, Greece, on Nov. 12, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

China’s War

The Trump administration has highlighted the national security threat posed by China’s market manipulations, responding with trade policy, state-funded production ventures, and the launch of a $12-billion critical minerals stockpile called Project Vault.

“China’s attempt to cut off our supplies of critical minerals was a declaration of economic war against the United States and a threat to supply chains around the world,” Rep. John Moolenaar (R-Mich.), chairman of the U.S. House Select Committee on the CCP, said in a statement following Trump’s early February announcement of Project Vault.

A 2025 investigation by the select committee revealed how China has weaponized its control of the minerals market—including with state subsidies and zero-interest loans to support global acquisitions, by manipulating prices to favor its national security interests, and by suppressing prices in order to further acquisitions and dominate the global supply chain.

Europe finds itself in a similar position to the United States, perhaps more so due to its ambitious climate and energy agenda. While embracing further cooperation with China on climate-related goals, it has also introduced strategic plans and funding to diversify its supply.

But according to a February report by the European Court of Auditors, so far those efforts have produced little result.

While recent legislation has set a strategic course, auditors note, its targets “lack justification” and diversification efforts have not produced tangible results or addressed bottlenecks in domestic production and recycling. Europe’s high energy costs and lack of advanced processing technology further hinder it from becoming competitive.

Most strategic projects, the report notes, will struggle to secure supply for the EU by 2030.

Throughout Europe, the report notes, “lengthy and complex permitting is still a significant bottleneck,” as are environmental and social considerations.

This is especially true in Greece, where community and legal opposition to mining projects is often robust.

Other projects, such as the open-pit gold mine run by Canadian company Eldorado, have faced fierce opposition and unrest over environmental and social impacts. X The company’s Skouries copper-gold mine in northern Greece faced years of delays over concerns including toxic dust, destruction of archeological sites, and forest clearing. It will see its first commercial output by mid-2026, according to the company’s website.

The European Commission recently clarified permitting for mining in Natura 2000 areas, such as those in Northern Chios, allowing projects that pass strict assessment, are considered beneficial to “overriding public interest,” or where there are no alternatives.

Europe’s drive for supply stability is only just beginning. Skirmishes such as the one on Chios are a prelude to how these tensions will unfold—between ecological conservation, national security and energy sovereignty.

Antimony

Antimony—antimónio as it is known in modern Greek—has in the past few years catapulted from obscurity to the forefront of the minerals race, as the United States and European Union both invest billions to boost domestic critical mineral production.

As Rear Adm. Peter J. Brown, a former homeland security and counterterrorism adviser to President Donald Trump, wrote in a recent op-ed in The Defense Post, “not all minerals are created equal.”

The next century of economic and military competition, he suggests, will be shaped by a handful of materials that have become indispensable in the information age—including copper, lithium, cobalt and antimony.

“Without reliable access to these minerals, the U.S. economy—and the U.S. military—would be paralyzed. Ensuring energy, storage and operational capability in new technologies requires securing these critical minerals now,” Brown said.

(Left) Antimony metal powder with 99.5 percent purity is shown in this file image. The metalloid is a key input for defense, artificial intelligence, and “green” technologies. (Right) Naturally crystallized antimony in quartz is shown in this file image. (Leiem/CC BY-SA 4.0, Styroks/CC0)

In particular, antimony is crucial for both defense and “green energy” industries—used in everything from armor-piercing bullets, precision optics and infrared sensors, to batteries, semi-conductors and solar panels.

At the current rate of production, it is projected to become one of the scarcest metals by 2050, according to several academic articles.

True to its name—roughly “not alone,” from the Greek “anti” (opposed) and “monos” (alone)—the lustrous metalloid is often found co-occurring with other elements, and typically extracted from highly toxic stibnite (antimony sulfide).

Documented use of antimony dates back thousands of years, employed by ancient civilizations in pottery, metal alloys and cosmetics—notably, the ancient Egyptians used it to produce black eye makeup—and later, in medicine.

Some of antimony’s toxic effects have been known for centuries. At least since the Middle Ages, it was considered a kind of poisonous panacea—used in small doses as a purgative and to treat “melancholia”—which some, including science writer John Emsley, suggest may have accidentally killed Mozart.

But by the 20th Century, the dangers of industrial exposure had become abundantly clear.

A Toxic Legacy

At the summit of a mountain road winding from Volissos to the abandoned antimony mines of Keramos, a sign melted by the fires—perhaps it used to note the dizzying elevation—bore a simple spray-painted protest: “kamia exoryxi”—which roughly translates to “no mining.”

Similar exhortations are scrawled in red across the stone ruins of 19th mining settlements, nestled in a verdant ravine near the hillside village of Keramos.

The mines here operated in the late 1800s and early 1900s, with another brief revival in the mid-20th century funded by the Marshall Plan.

A plaque near a small church graveyard memorializes 24 miners who died there, either from antimony-related illness or accidents. But many more suffered health impacts resulting from toxic exposure, according to a 2020 article published in the Greek minerals journal Oryktologica NEA.

Some older residents of nearby villages remember those times, of their fathers or grandfathers, and say officials have done little to assure them it won’t happen again.

Enjoying a morning cigarette and a glass of tsipouro, the local moonshine, at a Volissos café, Nikos Mixalakis said he was frustrated with the lack of information.

Nikos Mixalakis enjoys a cafe in Volissos, Greece, on Nov. 14, 2025. Mixalakis said he was frustrated by the lack of information about potential health impacts from toxic exposure. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

“When they mined antimonio before, many people were dead,” he said. “The truth is antimonio is no good for us. All of us will have a health problem if they are working there. Everything will die—everything.”

Theodouro points to Greece’s other mining ventures, including a growing gold industry, noting, “antimony is a hundred times worse than this. It’s cancer, it’s no nature, no animals, no people can stay alive after this.”

Even the United States has stopped producing it, he said.

Indeed, where the United States used to produce nearly all its own supply of the mineral, the introduction of stricter environmental laws starting in the 1970s contributed to a decline. The country’s last major mine, Idaho’s Stibnite Mine, shuttered in the late 1990s. Perpetua Resources, which owns the mine, re-opened it in September 2025 as a source of both gold and antimony, but the re-opening faces opposition in court over environmental concerns.

Methods have evolved since the Keramos mines were last in operation, and technological breakthroughs promise to revolutionize extraction and reduce environmental impact.

But antimony is considered one of the most toxic heavy metals, and along with co-occurring metals such as lead and arsenic, can induce severe health effects, from pneumoconiosis, cardiac and gastrointestinal effects to cancer and developmental disorders. Numerous peer-reviewed studies have shown deleterious impacts on environment and human health in mining areas in China, home to the world’s largest stibnite reserves.

Buildings that once housed mining personnel now sit abandoned near the village of Keramos, Greece, on Nov. 14, 2025. The mines here operated in the late 1800s and early 1900s, with another brief revival in the mid-20th century funded by the Marshall Plan. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

While antimony occurs naturally in stone, its concentration and mobility are substantially increased by mining, smelting, and related industrial emissions. The result is drinking water contamination and heavy metal bioaccumulation in crops.

Heavy metals are known to pose cumulative risks, not just acute ones, persisting long after mining ceases and making their way up the food chain.

Metals involved in antimony mining are known to be chronically toxic and potentially carcinogenic, especially when elements enter ground water through runoff, while skin contact and consumption of contaminated water pose a range of risks to residents, recent research has shown.

In the case of Chios, government officials have vowed strict environmental controls would accompany any exploration or exploitation.

Companies that submitted bids in response to the government’s 2025 tender, including TERNA, Heracles Group, Gaia Meleton and Geotest Chionis, did not respond to inquiries from The Epoch Times.

Local officials, including the mayor of Chios and the president of the Chios Council, did not respond to repeated requests regarding the proposed antimony project.

Mining offices in Athens, Greece, on Nov. 16, 2025. As multinational mining operations expand across the country once again, Greece faces a new war: externally, against China’s malign stranglehold on the future of technology and, internally, over how its natural resources will be used. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

‘A Major Shift’

As Greek islands go, Chios is relatively underdeveloped.

It’s the only place in the world that produces “masticha” or mastic gum, a resin collected from a Mediterranean shrub that has been used as a medical panacea for thousands of years. And it has maintained a robust tourism industry without being colonized by the all-inclusive megadevelopments typical of other islands.

So far this has led to a “balanced and sustainable” model, Costas Moundros, president of the Chios Tourism Organization, told The Epoch Times.

“Its two principal pillars are maritime activity and the production of mastic, which form the foundation of its economic and cultural identity,” he said. “These sectors are the primary drivers of growth.”

Kostas Moundros, president of the Chios Tourism Organization, stands near his office in Chios, Greece, on Nov. 13, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

The move to extract antimony, he said, represents a “major shift” with potentially profound consequences.

“The state has effectively placed citizens before a new reality that could alter the social, environmental, and economic landscape of the island,” Moundros said.

“This has occurred without prior consultation, public dialogue, or a transparent assessment of the potential risks and benefits.”

Environmental groups, including the Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage, last year opposed the proposed mining project, citing a serious threat to “the area, which is designated as a Natura 2000 protected zone,” as well as to the health of surrounding communities and to agricultural production of mastic

After a public outreach effort critics derided as “authoritarian and unilateral,” social uproar led to a period of public comment, with input from scientists, cultural organizations and other stakeholders.

Attorney Panos Lazaratos, who has filed petitions to annul the project, in a public forum in April 2025 indicated residents have a strong legal case, but stressed the struggle is far from over.

A quarry mine sits in view of a highway outside of Chios, Greece, on Nov. 12, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

In late 2025, civil servants in Chios City Hall shrugged when asked about the pause. “It’s temporary,” one told The Epoch Times. “It will start again.”

“Our community is united and determined to protect this small island from a project we believe could cause irreversible environmental and public health damage,” Theodorou said.

“We need help … But we don’t want it from the government.”

He gestured at the terraced groves, stone buildings and spectacular beaches surrounding Volissos.

“They want to make this a ghost village.”

Other half-empty villages, Theodorou surmised, may not put up such a fight.