SAN DIEGO—Deep in the remote Jacumba Mountains of southeastern San Diego County, the once celebrated, hard-fought Desert Line section of the San Diego–Arizona Eastern Railway is slowly deteriorating into the landscape it once conquered.

The railway, made up of 148 miles of railroad tunnels, tracks, and trestles, once connected San Diego and Yuma, Arizona, through Mexico, and on to connections in the east.

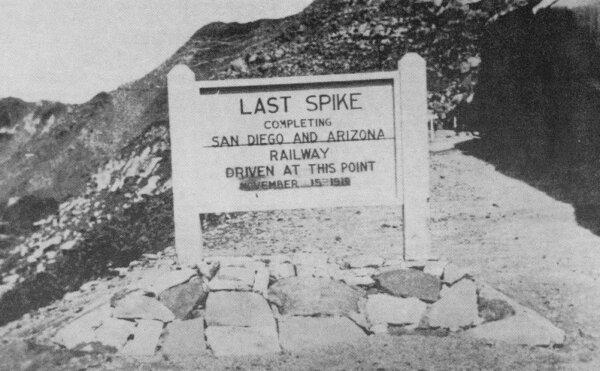

Started in 1907 and completed in 1919, the railway was dubbed the “Impossible Railroad” by early 20th-century naysayers who believed that the inhospitable desert terrain and extreme temperatures were far too treacherous for anything, much less a railroad.

Yet thanks to the vision and determination of sugar magnate John D. Spreckels, it’s one of the most significant and captivating engineering feats in American railroad history.

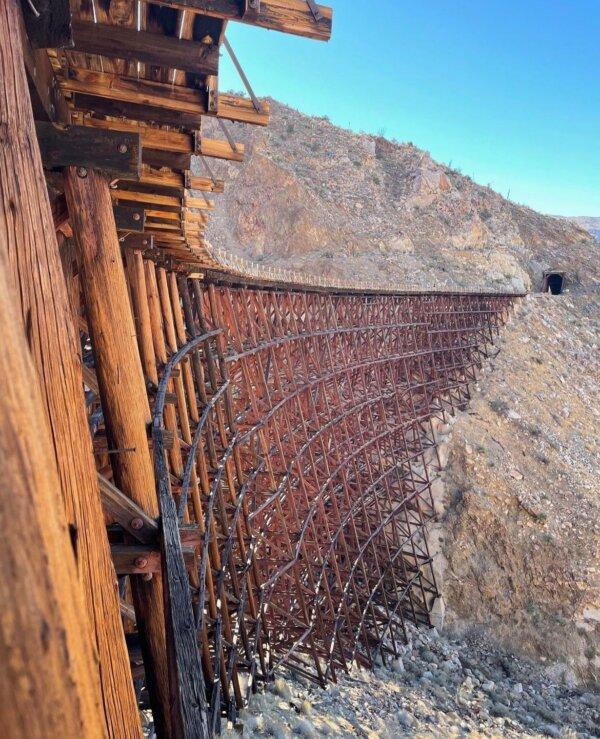

The most foreboding section of the railway is that of the 70-mile Desert Line route, an 11-mile trek across the steep and jagged Carrizo Gorge in California that rises and falls by more than 3,700 feet. The route passes through 21 rocky tunnels and over 14 wooden trestles, including one that defies both logic and gravity, Goat Canyon Trestle.

Eight miles into the gorge and just beyond a blind bend in the mountainside, Goat Canyon Trestle is one of the world’s most remarkable engineering accomplishments, towering a breathtaking 185 feet high and stretching 633 feet across the massive ravine below.

Engineers designed it at a 14-degree curve to withstand the battering winds of the canyon.

Goat Canyon Trestle along the San Diego–Arizona Eastern Railway. (Courtesy of Historic Vids)

But despite its magnificent past, the railway has been left to rot in scorching heat and freezing rain, subjected to earthquakes, arson fires, and gravel avalanches.

Since its demise, hikers and adventure-seekers searching for a glimpse of the mighty trestle violate numerous “No Trespassing” signs to risk the precarious winding, boulder-strewn trails, all with one goal in mind: to bear witness to one of the loftiest human accomplishments ever pursued in conquering such inhospitable terrain.

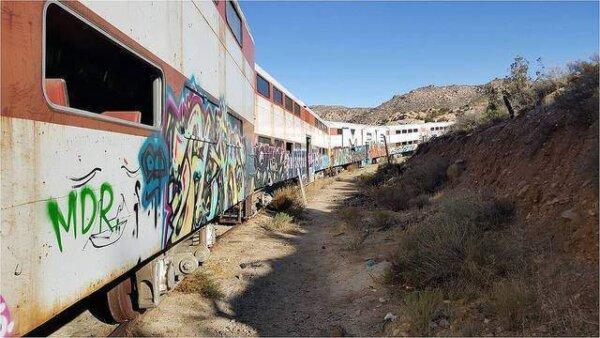

Mysterious, abandoned rail cars emblazoned with graffiti stand frozen in time along the route, bearing little resemblance to their former grandeur and significance in the annals of American history.

(Courtesy of Hidden San Diego)

A Testament to Great American Ingenuity

In the early 20th century, travel to the remote Mexican border town of San Diego, California, was nearly impossible.

That changed when Mr. Spreckels decided to leave his swanky city of San Francisco for the southern tip of California, where the temperate weather and beautiful coastlines of San Diego were backdrop to a large seaport, plenty of natural resources, and a gateway to Mexico and beyond.

At the turn of the century, San Diego was a burgeoning but isolated town with no major rail networks connecting it anywhere outside the area.

Mr. Spreckels understood the many desirable aspects of the region and knew if he could connect the port of San Diego to a rail line, commerce and passengers would follow.

The first San Diego–Arizona Railway through passenger train arrives at San Diego's Union Station passenger terminal to officially open the line on Dec. 1, 1919. (Public Domain)

Building a railway would boost the city’s economy and solidify its status as a major port and gateway to the Pacific, rivaling that of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

What Mr. Spreckels didn’t realize was the unparalleled challenges that the treacherous, inhospitable terrain would impose. His team of surveyors, engineers, and the thousands of miners and railway workers would toil in blistering heat and freezing temperatures to complete the engineering miracle.

The railway was the most expensive railroad ever built, costing a whopping $19 million. It was the first modern line to move passengers and cargo to and from San Diego via its furthest eastbound stop in El Centro, California, where connections could be made to Southern Pacific’s transcontinental service.

Over the years, the project was fraught with natural disasters, including floods and avalanches, as well as political strife such as the Mexican Revolution, which posed challenges due to the railroad’s proximity to the U.S.–Mexico border.

Finally, in 1919, the railway was complete, connecting San Diego to El Centro, zigzagging internationally back and forth through Mexico, and by extension to broader U.S. rail networks such as Southern Pacific.

Mr. Spreckels’s dream had finally become a reality, allowing travel and commerce to the rest of the country.

Determining the Railway’s Future

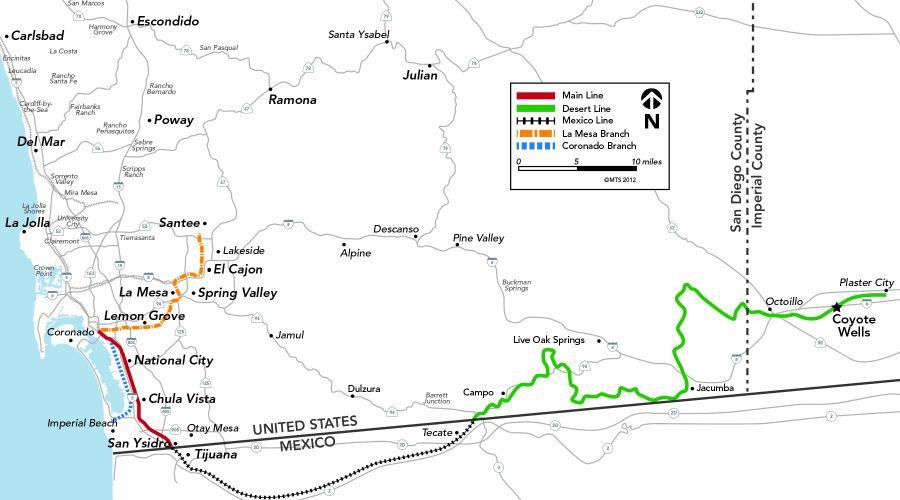

In 1979, the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System purchased 108 miles of the railroad, including the 70 miles of Desert Line track running through Campo and Jacumba, both in California.

Unfortunately, that segment of the track discontinued freight service in 2008 because of its deteriorating condition. With a struggling economy challenging the entire United States at the time, the railroad’s future looked bleak.

Then, beginning in 2012, a series of agreements between the San Diego Metropolitan Transportation System and various railroad companies in the United States and Mexico to connect the 70-mile Desert Line section in San Diego with factories in Mexico were attempted.

The San Diego–Arizona Eastern Railway map. (Courtesy of San Diego Metropolitan Transit System)

For a time, it appeared that the railroad might finally have a future. But in 2020, the most recent agreement was breached and the project was abruptly canceled.

Mark Olson, transit system director of marketing and communications, told The Epoch Times, “[The Metropolitan Transit System] terminated its lease, that included the area of the proposed railroad reconstruction project, with Baja California Railroad effective June 28, 2020.”

Mr. Olson said grant funds for a feasibility study to determine the future of the Desert Line were awarded in 2022, but Caltrans hasn’t yet commenced the study.

“There is no current public or private project to reconstruct the Desert Line,” he said.

Only time will tell whether Mother Nature will eventually reclaim the storied piece of history or modern engineers will bring it back to life.

(Courtesy of the Pacific Southwest Railway Museum Association)

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the name of John D. Spreckels. The Epoch Times regrets the error.